Komodo Dragons (Varanus komodoensis) are the world’s largest living lizards, found exclusively on several Indonesian islands. These reptiles can reach up to 3.13 meters (10 feet 3 inches) in length and weigh up to 166 kg (366 pounds). Their formidable size, powerful limbs, and predatory adaptations have made them one of the most fascinating subjects in herpetology and wildlife conservation.

Characterized by their robust build, powerful limbs with sharp claws, and rough grayish-brown skin, Komodo Dragons possess a sophisticated venom delivery system. Specialized glands in their lower jaw secrete toxins that cause rapid drops in blood pressure and prevent clotting in prey. This venom works with numerous bacterial strains in their saliva, creating a lethal combination that ensures prey succumbs even after escaping an initial attack.

Their evolutionary history spans approximately 4-5 million years in the Indonesian archipelago. Isolated development on the islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, and Gili Motang has produced a unique apex predator perfectly adapted to its environment.

Their behavior changes significantly with the seasons – conserving energy during the dry season (May-October) when they also mate, while showing increased activity during the wet season (November-April).

As ectotherms, Komodo Dragons carefully regulate their daily activities, with peak movement during morning and late afternoon hours. They employ various hunting techniques, from patient ambushes to scavenging, and can detect prey from great distances using their forked tongues and Jacobson’s organs.

Today, with fewer than 1,400 mature individuals in the wild, Komodo Dragons are classified as endangered by the IUCN. They face challenges from habitat loss, climate change impacts, and human encroachment. Conservation efforts through protected reserves, breeding programs, and educational initiatives aim to preserve these iconic reptiles.

In this article, we’ll explore the extraordinary world of Komodo Dragons, examining their physical characteristics, habitat requirements, hunting techniques, and conservation status – investigating what makes these ancient predators one of nature’s most impressive evolutionary success stories.

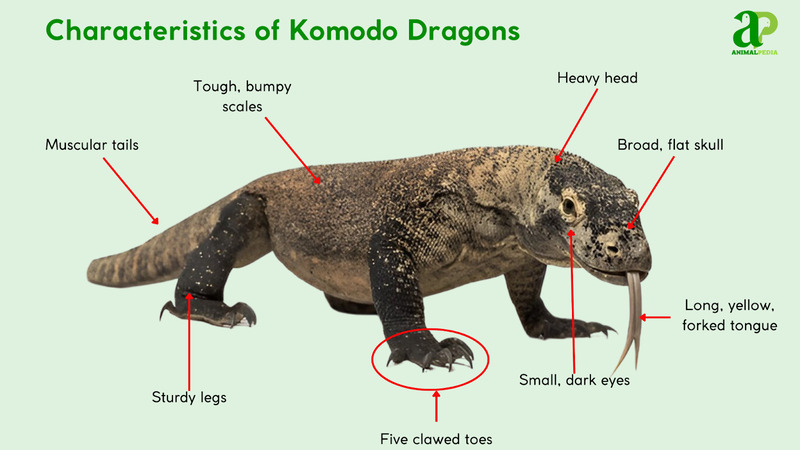

What does the Komodo dragon look like?

The Komodo Dragon has a robust, elongated body with powerful limbs that end in sharp claws, ideal for grasping and tearing prey. Their skin is covered in tough, bumpy scales that provide protection and are a gray-brown color, blending in with their habitat. The dorsal side often features a variegated pattern of lighter and darker shades, aiding in camouflage during hunting.

The head of a Komodo dragon is streamlined, tapering to a pointed snout filled with razor-sharp teeth. Their small eyes can detect movement up to 300 meters away, with high color discrimination. Besides, the distinctive forked tongue collects chemical particles, enabling them to sense carrion from 10 kilometers away and precisely track prey using their advanced vomeronasal system.

Their legs are sturdy and muscular, supporting their massive body, and end in sharp claws used for gripping prey during hunting. Compared to other similar species, the Komodo dragon is distinguishable by its larger size and unique hunting techniques, such as using bacteria-ridden saliva to weaken and eventually kill its prey.

When compared to their closest venomous relative, the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), Komodo dragons differ dramatically in size (being nearly 10 times larger), possess a more laterally compressed tail, and lack the Gila monster’s distinctive bead-like scales and bright warning coloration.

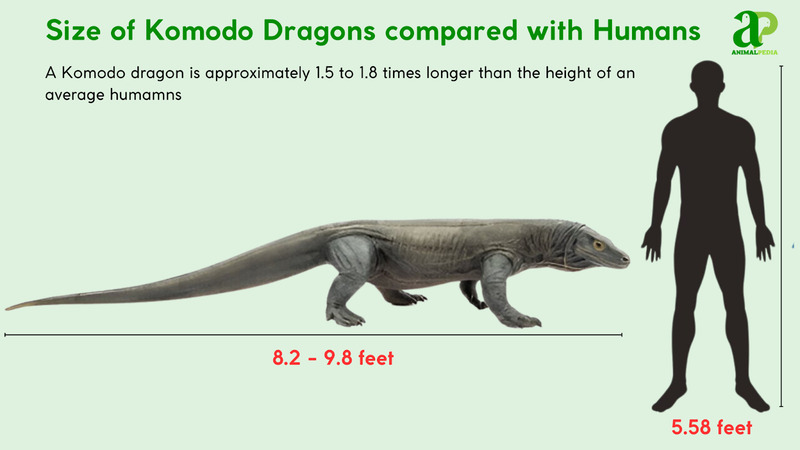

How big do Komodo dragons get?

Komodo dragons can grow to be 10 feet long and weigh up to 366 pounds, making them the biggest lizard on Earth. The largest recorded Komodo dragon was discovered on the Indonesian islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, and Gili Motang. This colossal specimen measured a staggering 3.13 meters (10 feet 3 inches) in length and weighed approximately 166 kg (366 pounds).

These measurements were confirmed by the Komodo Dragon Species Survival Commission, based on extensive field research and documented by the Komodo National Park authorities.

Furthermore, their size varies by sex and individual. Adult male Komodo dragons typically reach lengths of around 2.5 to 3 meters, while females are slightly smaller, measuring between 2 to 2.5 meters in length. In terms of weight, males can weigh up to 90 kg (200 pounds), whereas females are lighter, averaging around 70 kg (154 pounds).

Below is a table summarizing the main differences in length and weight between male and female Komodo dragons:

|

Gender |

Length Range |

Weight Range |

| Male | 8.2 – 9.8 feet (2.5 – 3 meters) | Up to 198 pounds (90 kg) |

| Female | 6.6 – 8.2 feet (2 – 2.5 meters) | Up to 154 pounds (70 kg) |

What are the unique physical characteristics of a Komodo dragon?

The Komodo dragon possesses a sophisticated venom delivery system that has revolutionized our understanding of this species’ hunting strategy.

According to the evolutionary dynamics of venom toxicity in varanid lizards,” – Published in Nature Ecology & Evolution by Hocknull et al. (2019), it is identified that specialized multicompartmental venom glands are in the lower jaw. These glands secrete toxins through ducts distributed between the pleurodont teeth, creating an effective delivery mechanism during bites.

The venom contains anticoagulant proteins, including phospholipase A2 and natriuretic peptides, which cause vasodilation and hypotensive shock. According to Microbial Research by Merchant et al. (2017) determined venom concentration ranges from 0.1-0.8 mg/kg of prey body weight. These compounds prevent blood clotting and induce rapid drops in blood pressure, accelerating prey collapse.

Anatomy

The Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), the largest living lizard, exhibits specialized physiological systems adapted to its role as an apex predator:

- Respiratory System: Features large, multi-chambered lungs typical of monitor lizards, more advanced than those of most reptiles. Air enters through the nostrils, travels down the trachea, and is exchanged in the alveoli, supporting its active predatory lifestyle. Komodo dragons can increase breathing rates during exertion, such as hunting or combat.

- Circulatory System: Possesses a four-chambered heart (two atria, two ventricles) with a functional separation, a rare trait among reptiles. This allows more efficient oxygen delivery to muscles and organs, supporting bursts of activity and a higher metabolism than most lizards. Blood also carries anticoagulant compounds from venom glands.

- Digestive System: Includes a highly expandable stomach and strong gastric acids, capable of digesting bones, hooves, and tough hides. The short intestines process large, infrequent meals (e.g., deer, pigs, or carrion). Salivary glands produce venom rich in bacteria and toxins, which weakens prey and aids digestion by accelerating tissue breakdown.

- Excretory System: Features paired kidneys that excrete nitrogenous waste as uric acid through a cloaca, minimizing water loss—an adaptation for its dry island habitats (e.g., Komodo, Rinca). This efficiency allows survival with limited freshwater access, relying partly on moisture from prey.

- Nervous System: Comprises a large brain and spinal cord, with advanced sensory capabilities. Its forked tongue and Jacobson’s organ detect chemical cues from prey or carrion up to 4-9.5 kilometers (2.5-6 miles) away, depending on wind. This system drives its calculated stalking and ambush tactics.

These systems collectively enable the Komodo dragon’s dominance in its environment, combining endurance, lethal predation, and resilience in the rugged, resource-scarce islands of Indonesia.

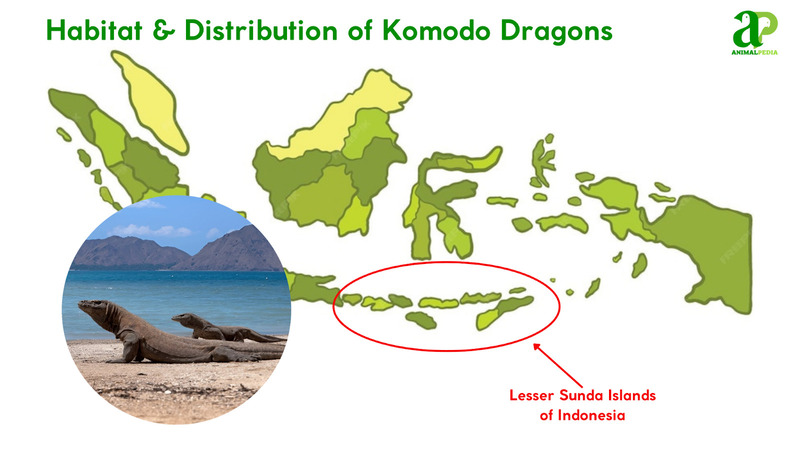

Where do Komodo dragons live?

The Komodo Dragon is primarily distributed in the Lesser Sunda Islands of Indonesia, with the largest population found on Komodo Island and its neighboring islands. These areas are characterized by a rugged terrain of savannas, monsoon forests, and coastal lowlands, providing diverse habitats for the dragons to thrive. The warm and humid tropical climate suits their ectothermic nature, enabling them to regulate their body temperature effectively.

According to “The evolutionary dynamics of venom toxicity in varanid lizards,” in Nature Ecology & Evolution, by Hocknull, S. A., et al. (2019), Komodo dragons or their ancestors have occupied the Indonesian archipelago, including the Lesser Sunda Islands, for 4-5 million years ago.

Recent research has focused on the genetic diversity and population dynamics of Komodo dragons, shedding light on their long-term residency and adaptation to these island environments.

How do seasonal changes affect their behavior?

Komodo dragons display distinctive behavioral patterns that shift dramatically between dry and wet seasons on their Indonesian island habitats. These seasonal adaptations are critical to their survival in a challenging environment with fluctuating resource availability.

The dragons behave very differently across seasons. During the dry season, they save energy by moving less and can go without eating for weeks. In the wet season, they move around more and eat weekly. Breeding happens in the dry season, while babies hatch in the wet season. They stay in smaller areas during the dry season, but travel farther and swim between islands during the wet season.

- Dry Season (May-October)

In this period of time, Komodo dragons reduce movement by 20-30%, conserving energy due to food scarcity. They extend daily basking to 4-6 hours to maintain optimal body temperatures of 35-38°C, making the most of cooler, arid conditions while strategically ambushing prey that clusters around limited water sources.

Mating occurs from May to August, with males becoming more active and aggressive in competition for females. Nesting follows in September when females select dry, stable soil for egg-laying.

- Wet Season (November-April)

Dragons swim more frequently between islands, showing heightened activity with reduced basking (2-3 hours) due to naturally higher ambient temperatures.

Adults range more widely (2-3 km daily versus 1 km in the dry season), as scattered prey requires more extensive foraging. Scavenging increases to 30-40% of their diet, aided by flood-exposed carrion.

Eggs hatch around April-May when warmth (28-32°C) and high humidity (80-90%) create ideal conditions. Hatchlings immediately climb trees to escape flooding and predators.

What is the behavior of a Komodo dragon?

Komodo dragons stand as one of nature’s most fascinating predatory species, embodying an extraordinary blend of behaviors as follows.

- Diet: Apex predators use venomous bites and keen senses to ambush prey, primarily hunting carrion and large mammals with extraordinary precision.

- Hunting Mechanisms: Patiently wait along game trails, using a venomous bite containing proteins that induce shock and inhibit blood clotting.

- Daily Activity Patterns: Ectothermic creatures strategically move between sun and shade, maintaining optimal body temperature throughout the day.

- Locomotion Capabilities: Highly adaptable movers excelling in walking, running, swimming, and climbing across diverse island terrains.

- Social Structure: Solitary predators fiercely defending territories, minimally interacting except during feeding or mating opportunities.

- Communication: Communicate through sophisticated visual and olfactory signals, using body language and scent-detection mechanisms.

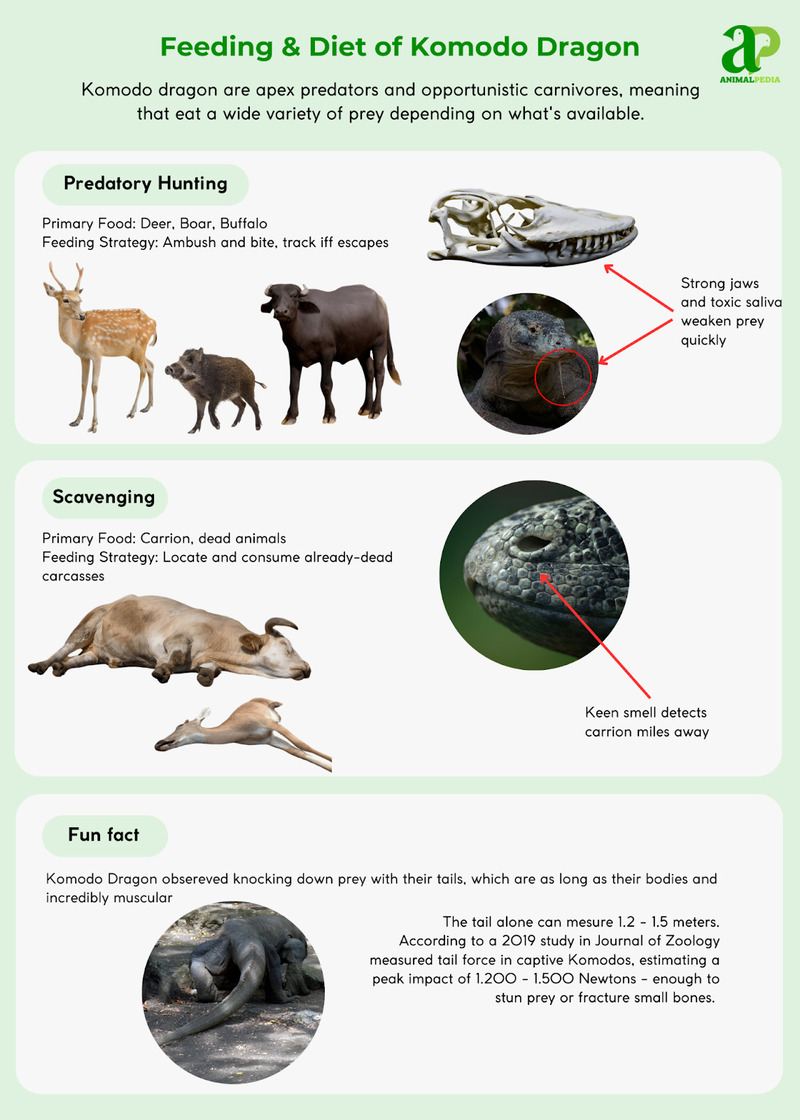

What do Komodo dragons eat?

Komodo dragons are carnivorous animals, primarily feeding on carrion and the carcasses of animals such as pigs, deer, and cattle. While they’ve been known to eat smaller dragons and even adults, scavenging for dead animals is their main feeding strategy. Their venomous bite aids in subduing prey, causing fatal blood loss and preventing clotting. Unlike some carnivores, Komodo dragons don’t typically target humans as prey.

Diet by age

Komodo dragons display significant dietary shifts throughout their lifespan, adapting their feeding strategies to match their growing size and hunting capabilities.

- Hatchlings (0-1 Year)

These tiny dragons primarily consume insects—ants, grasshoppers, and beetles—supplemented with small geckos and bird eggs. Their arboreal lifestyle allows them to forage safely in trees, away from cannibalistic adults. This protein-rich diet supports their rapid early growth while minimizing competition with larger dragons.

- Juveniles (1-5 Years)

As they grow, juveniles transition to small vertebrates, including lizards, snakes, rodents, and occasional bird nestlings. They begin incorporating carrion scraps into their diet, developing the scavenging behavior crucial for later life stages. Their diet gradually shifts as their body mass increases and hunting skills develop.

- Subadults (5-7 Years)

With increased size and strength, subadults target medium-sized prey such as Timor deer fawns, wild boar piglets, and large reptiles. Carrion forms a significant portion of their diet.

- Adults (7+ Years)

Full-grown Komodo dragons become formidable predators capable of hunting large mammals, including deer, boar, and even water buffalo. Adults are efficient scavengers and opportunistic cannibals, consuming juvenile dragons when available.

Diet by gender

There are no significant differences in eating behaviors between males, females, and young Komodo dragons. They typically tear chunks of meat from their prey, as their jaws aren’t adapted for chewing. If they encounter prey larger than themselves, they may resort to tearing smaller pieces or rely on scavenging for easier meals.

Diet by seasons

Seasonal dietary changes aren’t particularly evident in Komodo dragons, as they’re opportunistic feeders with a varied diet year-round.

The following infographic illustrates the two primary feeding approaches of Komodo dragons: active predatory hunting and opportunistic scavenging.

How do Komodo dragons hunt their prey?

Komodo dragons rely on their keen sense of smell to detect prey from afar, allowing them to patiently wait along game trails or near watering holes for unsuspecting animals to pass by.

They’re skilled ambush predators, utilizing their powerful jaws filled with deadly bacteria and venom to incapacitate their victims quickly.

Unlike other predators of their size, Komodo dragons possess a unique combination of stealth, patience, and specialized hunting mechanisms, making them formidable apex predators in their ecosystem.

Their ability to deliver a lethal bite that induces rapid blood loss sets them apart from other species and highlights their exceptional hunting prowess.

Are Komodo dragons venomous?

Yes, the Komodo Dragon is venomous. Recent scientific studies have confirmed that Komodo dragons possess venom glands in their lower jaws, which are used to release toxins when they bite their prey.

The venom contains various proteins that can induce shock, inhibit blood clotting, and lower blood pressure, leading to the eventual demise of the bitten animal. This venomous trait sets the Komodo dragon apart from other reptiles and aids in its hunting strategy by efficiently incapacitating larger animals.

This unique combination of venom and bacterial pathogens in its saliva makes the Komodo dragon a formidable predator in its ecosystem.

When are Komodo dragons most active during the day?

The Research by Ariefiandy et al. (2015) documented peak activity between 6-9 AM and 4-7 PM. As ectotherms, their behavior is largely driven by the need to maintain optimal body temperatures of 35-38°C (95-100°F), which requires strategic movement between sun and shade throughout the day.

Komodo dragons exhibit a crepuscular activity pattern, being most active during the early mornings and late afternoons. They utilize these times to bask in the sun, warm up, and search for prey in relatively cooler temperatures. As the day progresses and temperatures rise, they seek shelter in shady areas to conserve energy.

How do Komodo dragons move on land and water?

On land, Komodo dragons utilize their powerful limbs to move swiftly, sprinting short distances with ease for hunting or territorial defense. In the water, Komodo dragons showcase surprising swimming abilities, using their long tails to propel themselves gracefully. Their bodies undulate smoothly while swimming, allowing them to navigate water swiftly and with agility.

Komodo dragons are renowned for their diverse locomotion capabilities, adapted to the diverse habitats of the Indonesian archipelago. Ecological studies have identified five primary modes of locomotion, each serving unique survival and predatory purposes across different life stages and environmental conditions.

- Walking

Characterized by a sprawling gait on four legs, moving low to the ground at an average speed of 4-5 km/h. This is the primary mode of movement during foraging and routine territorial exploration, allowing for energy-efficient movement across varied terrain.

- Running

Involves short, explosive bursts of speed reaching up to 20 km/h (12 mph). Typically used during hunting ambushes or to escape potential threats, demonstrating the dragon’s acceleration and agility in critical moments of predation or self-preservation.

- Swimming

Employs lateral undulation of body and tail, achieving speeds of 1-2 m/s. Komodo dragons can effectively cross water distances up to 500 m between islands, showcasing their impressive aquatic mobility and adaptability to the archipelagic environment.

- Climbing

Predominantly observed in hatchlings and juveniles. Using sharp claws, they scale trees as a crucial survival strategy, seeking safety from predators and accessing small prey in arboreal environments. This locomotion mode is critical for young dragons’ survival.

- Standing

An infrequent posture where the dragon rears up on its hind legs and tail. Used briefly for enhanced visual observation or during confrontational interactions, lasting only a few seconds. This vertical stance allows for improved situational awareness and potential intimidation.

Despite their large size, they effortlessly transition between land and water, showcasing flexible adaptability. This versatility in movement enables them to hunt effectively in diverse environments, making the Komodo dragon a formidable predator both on land and in the water.

Do Komodo dragons live alone or in groups?

Komodo dragons exhibit a solitary social structure, preferring to live and hunt alone. They establish and fiercely defend their territories, which are crucial for their survival and reproductive success. As solitary predators, they don’t form social hierarchies or live in groups.

However, during feeding frenzies near a carcass, they may tolerate the presence of other Komodo dragons for a brief period. This behavior allows them to efficiently hunt and secure food without competition from others.

Their territorial behavior plays a vital role in maintaining their dominance as apex predators in their habitat, helping them avoid conflicts over resources and ensuring their individual survival.

How do Komodo dragons communicate with each other?

Komodo dragons communicate primarily through visual signals and olfactory cues. They use body language, like head bobbing, tail wagging, and hissing, to convey messages of dominance, submission, or warning.

In addition, they rely heavily on their sense of smell by flicking their long, forked tongues to collect scent particles. These scents are then processed in the Jacobson’s organ in their mouth, allowing them to interpret information about prey, mates, and potential threats.

This specialized sense of smell helps Komodo dragons navigate their environment and communicate effectively with other members of their species. Compared to other animals in the same family, Komodo dragons have a unique combination of visual and olfactory communication methods that make them stand out in the animal kingdom.

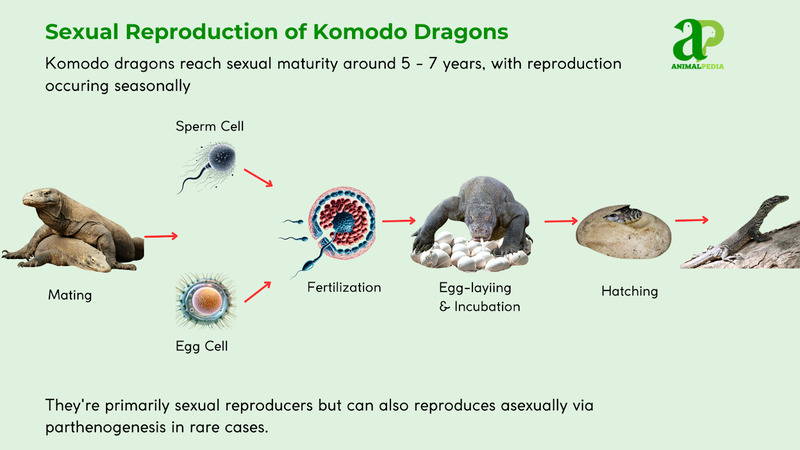

How do Komodo dragons reproduce?

The Komodo dragons reproduce primarily through sexual reproduction, with a rare ability for asexual reproduction via parthenogenesis.

The breeding season for Komodo dragons typically begins around May and lasts through August. During this time, male dragons become more aggressive, fighting each other to establish dominance and gain access to females. The males actively seek out the females, often following them while flicking their tongues to pick up pheromones. The courtship involves a series of behaviors such as head bobbing, tail whipping, and even gentle biting to test the female’s receptiveness.

Once mating occurs, the female will lay a clutch of around 20-30 eggs, each weighing about 1 pound on average. These eggs are buried in nests dug by the female in mounds of decaying vegetation to provide the necessary heat for incubation. The female fiercely guards the nest site against potential predators during the 7-8 month incubation period.

In some cases, nesting may be interrupted if conditions aren’t favorable, leading to the reabsorption of the eggs.

After hatching, the baby Komodo dragons are on their own and face significant threats from predators, including adult Komodo dragons that may see them as prey. It takes several years for the young dragons to reach maturity at around 8-9 years of age.

How long do Komodo dragons live?

The average lifespan of a Komodo dragon is around 30 to 50 years in the wild, showcasing their resilience and adaptation in their natural habitat. Komodo dragons hatch from eggs after 7-8 months, grow as arboreal hatchlings, then become terrestrial juveniles. Reaching maturity at 7-9 years, adults hunt large prey and reproduce, with females laying 15-30 eggs. They live 30-50 years, aging from predators to scavengers.

Interestingly, male Komodo dragons tend to have slightly shorter lifespans compared to females. They start their life cycle with female dragons laying eggs in burrows they dig themselves. The young hatchlings emerge around April or May, measuring about 45 cm long. Initially seeking safety in trees, they gradually grow into formidable hunters, preying on smaller animals and even ambushing larger ones.

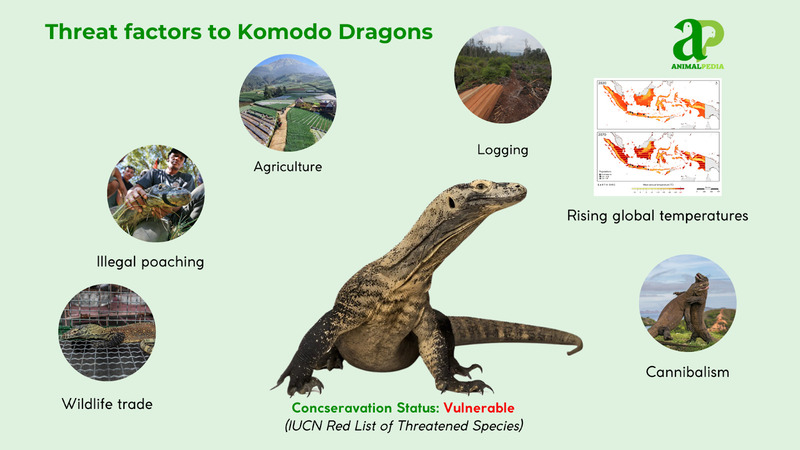

What are the threats or predators that Komodo dragons face today?

Komodo dragons face several threats to their survival in the wild.

- Habitat Loss

Human activities like logging, agricultural expansion, and urban development are progressively eroding the natural habitats of Komodo dragons. These interventions dramatically reduce available territories, forcing dragons into smaller, fragmented zones that compromise their hunting and breeding capabilities.

The shrinking landscape disrupts their traditional movement patterns and limits access to critical resources, pushing these reptiles closer to ecological vulnerability.

- Wildlife Trade and Poaching

Illegal hunting targets Komodo dragons for their valuable skins, meat, and body parts, primarily driven by traditional medicine markets and the exotic wildlife trade. Poachers exploit the dragons’ limited population and restricted geographic range, creating significant pressure on their survival.

Each captured or killed dragon represents a substantial loss to the species, undermining conservation efforts and threatening the delicate ecological balance of their island habitats.

- Climate Change Impacts

Rising global temperatures are transforming the Komodo dragons’ island ecosystems, creating unprecedented challenges for their survival. Changing climate patterns disrupt prey distribution, alter vegetation, and increase the frequency of extreme weather events.

These environmental shifts compromise the dragons’ ability to hunt effectively, maintain optimal body temperatures, and reproduce successfully, potentially accelerating their path towards ecological vulnerability.

- Intraspecies Threats

Cannibalism emerges as a significant internal challenge for Komodo dragon populations, particularly threatening juveniles and smaller individuals. Larger dragons often prey on younger members of their species, creating a complex and brutal social dynamic.

This behavior, combined with intense territorial competition, adds another layer of survival challenge beyond external environmental threats, highlighting the species’ brutal yet fascinating ecological interactions.

Are Komodo dragons endangered?

The Komodo dragon is classified as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). The IUCN Red List categorizes the species as vulnerable to extinction. The 2021 IUCN Red List assessment, authored by Jessop and colleagues, estimates fewer than 1,400 mature (adult) Komodo dragons in the wild. These numbers are alarmingly low and indicate a significant decline in their population.

The main threats contributing to the endangerment of Komodo dragons include habitat loss, climate change impacts like rising sea levels leading to habitat destruction, and human activities such as hunting, poaching, and habitat destruction. These factors collectively put immense pressure on the survival of these fascinating lizards.

Conservation efforts are crucial to prevent further decline in Komodo dragon populations and to secure their future in the wild. By addressing the primary threats and implementing conservation strategies, we can work towards ensuring the long-term survival of this iconic species. Stay informed about the ongoing conservation initiatives dedicated to protecting the Komodo dragon and its habitat.

What conservation efforts are underway?

Conservation efforts for the endangered Komodo dragon involve various specific initiatives aimed at protecting this iconic lizard species. The Government of Indonesia, along with key organizations such as the Komodo Survival Program and the Komodo Conservation Program, has taken significant steps to safeguard the dragons and their habitats.

Specific conservation efforts include the establishment of protected areas not only on Komodo Island but also on Rinca and Gili Motang islands. These protected regions serve as crucial habitats for Komodo dragons, ensuring they have sufficient space to roam freely without human interference.

Furthermore, the Komodo National Park was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1991, providing additional international recognition and support for conservation efforts.

In terms of legal protection, Indonesia enacted laws to safeguard the Komodo dragon, making it illegal to harm, trade, or poach these creatures. Strict enforcement measures have been implemented to prevent illegal activities that threaten the survival of Komodo dragons.

Breeding programs have also played a crucial role in the conservation of Komodo dragons. The successful breeding program at Bali’s Taman Safari Indonesia has resulted in the hatching of numerous healthy Komodo dragon hatchlings. These breeding programs aim to increase the population of Komodo dragons in captivity, providing a safety net against the species’ declining numbers in the wild.

Conclusion

The Komodo dragon is a fascinating creature with its unique appearance, habitat, and behaviors. Living in the Indonesian islands, these impressive predators have sharp claws, tough scales, and a venomous bite. They exhibit territorial behaviors and rely on their keen senses to hunt efficiently. Despite facing threats from habitat loss and poaching, efforts are being made to protect these incredible animals. Learning about the Komodo dragon is truly an exciting adventure!