How are Animals classified?

Animals are classified based on their anatomy, physiology, genetics, and evolutionary relationships. The classification follows a hierarchical system known as taxonomy, which includes different levels: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and Species.

The main classification criteria include body structure, mode of reproduction, body symmetry, and embryonic development. This hierarchical approach, first developed by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in 1735, provides scientists with a standardized method to categorize and study living organisms.

The animal kingdom (Kingdom Animalia) is a vast and intricate assembly of life, classified hierarchically to highlight evolutionary relationships and shared characteristics:

- Kingdom Animalia includes multicellular, heterotrophic organisms lacking cell walls, with specialized tissues and organ systems. Reproduction is mostly sexual, though asexual reproduction exists in some cases. Both invertebrates and vertebrates fall under this kingdom.

- Subkingdoms:

- Parazoa: Represented by sponges (Phylum Porifera), these animals lack true tissues and organs, exhibiting cellular-level organization.

- Eumetazoa: Includes most other animals, characterized by true tissues and organ-level organization, further divided by body symmetry (radial or bilateral).

- Major Phyla:

- Porifera: Asymmetrical filter-feeders like sponges.

- Cnidaria: Jellyfish and corals with radial symmetry and stinging cells.

- Platyhelminthes: Bilaterally symmetrical flatworms, often parasitic.

- Nematoda: Cylindrical roundworms with pseudocoelom.

- Annelida: Segmented worms like earthworms with a true coelom.

- Arthropoda: Insects and crustaceans with exoskeletons and jointed appendages, the largest phylum.

- Mollusca: Soft-bodied species like snails, often with shells.

- Echinodermata: Starfish with adult radial symmetry and a water vascular system.

- Chordata: Vertebrates and relatives possessing a notochord at some life stage.

- Classes of Vertebrates (Chordata):

- Pisces: Aquatic fish with gills.

- Amphibia: Dual life forms, like frogs.

- Reptilia: Scaled, cold-blooded reptiles.

- Aves: Feathered birds with beaks.

- Mammalia: Warm-blooded mammals with hair and mammary glands.

This hierarchical structure underscores the diversity of life forms, from simple organisms like sponges to complex mammals, facilitating the study and appreciation of biological diversity.

Animal Kingdom (Kingdom Animalia)

├── Subkingdom Parazoa

│ └── Phylum Porifera (Sponges)

│ └── Characteristics: Asymmetrical, no true tissues, filter-feeding.

└── Subkingdom Eumetazoa

├── Phylum Cnidaria (Jellyfish, Corals, Sea Anemones)

│ └── Characteristics: Radial symmetry, stinging cells (cnidocytes).

│

├── Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms)

│ └── Characteristics: Bilateral symmetry, flattened bodies, many parasitic.

│

├── Phylum Nematoda (Roundworms)

│ └── Characteristics: Cylindrical bodies, pseudocoelomate, found in diverse habitats.

│

├── Phylum Annelida (Segmented Worms)

│ └── Characteristics: Segmented bodies, true coelom.

│

├── Phylum Arthropoda (Insects, Crustaceans, Arachnids)

│ └── Characteristics: Exoskeleton, segmented bodies, jointed appendages.

│

├── Phylum Mollusca (Snails, Clams, Octopuses)

│ └── Characteristics: Soft bodies, often with a shell, distinct body regions.

│

├── Phylum Echinodermata (Starfish, Sea Urchins)

│ └── Characteristics: Radial symmetry as adults, water vascular system.

│

└── Phylum Chordata (Vertebrates and Relatives)

├── Subphylum Urochordata (Tunicates)

├── Subphylum Cephalochordata (Lancelets)

└── Subphylum Vertebrata (Vertebrates)

├── Class Pisces (Fishes)

│ └── Examples: Sharks, Salmon.

│

├── Class Amphibia (Amphibians)

│ └── Examples: Frogs, Salamanders.

│

├── Class Reptilia (Reptiles)

│ ├── Subclass Anapsida

│ │ └── Order Testudines (~360 species, Turtles, Tortoises, Terrapins).

│ └── Subclass Diapsida

│ ├── Order Crocodilia (~27 species, American Alligator, Nile Crocodile).

│ ├── Order Rhynchocephalia (1 species, Tuatara).

│ └── Order Squamata (~10,000 species).

│ ├── Suborder Lacertilia (~6,500 species, Lizards).

│ ├── Suborder Serpentes (~4,000 species, Snakes).

│ └── Suborder Amphisbaenia (~200 species, Worm Lizards).

│

├── Class Aves (Birds)

│ └── Examples: Eagles, Penguins.

│

└── Class Mammalia (Mammals)

└── Examples: Humans, Lions, Whales.

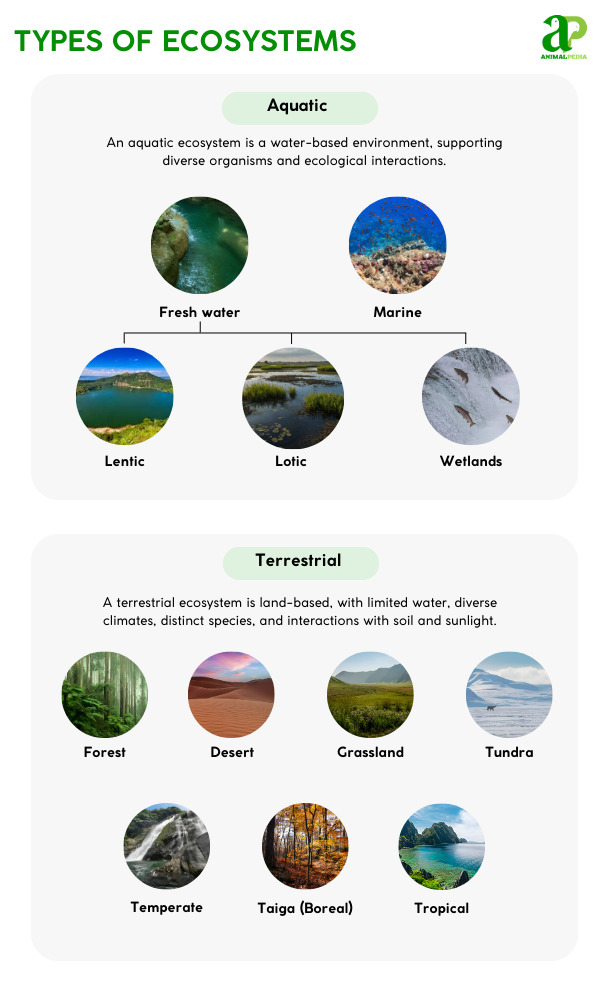

What are animals’ habitats and distribution?

An animal’s habitat is the natural environment where it lives, grows, and thrives. It provides essential resources like food, water, shelter, and space for reproduction. Habitats vary widely, including forests, deserts, oceans, grasslands, wetlands, and more, depending on the species and its specific adaptations.

They are categorized into:

- Terrestrial Habitats: Forests, grasslands, wetlands, and deserts, each supporting unique plant and animal communities adapted to specific climatic conditions and resources.

- Freshwater Habitats: Including rivers, lakes, ponds, and marshes, these are vital for species relying on aquatic systems for sustenance and reproduction.

- Marine Habitats: Spanning oceans and seas, they feature ecosystems like coral reefs, estuaries, and coastal zones, harboring species uniquely suited to saline conditions.

Additionally, animal distribution globally varies and is classified into:

- Cosmopolitan Distribution: Species found across diverse habitats on multiple continents, like killer whales (inhabiting all oceans) and house mice (thriving in varied environments).

- Endemic Distribution: Species restricted to specific regions, such as koalas, native exclusively to Australia’s eucalyptus forests.

However, the World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Report 2024 highlights a significant decline in monitored wildlife populations between 1970 and 2020. The report emphasizes habitat loss and degradation as primary drivers of these declines, with freshwater populations experiencing the steepest drop at 85%. The findings underscore the urgent need for conservation efforts to address habitat destruction and its impact on global biodiversity.

What is the relationship between an animal’s anatomy and its behavior?

An animal’s anatomy directly influences its behavior, shaping movement, feeding, sensory perception, and reproduction.

- Locomotion varies based on skeletal structure, from hydrostatic systems in worms to rigid skeletons in vertebrates.

- Feeding strategies align with movement, from sessile filter feeders to active predators.

- Sensory adaptations, including vision, chemoreception, and echolocation, help animals navigate their environment.

- Structural organization evolves from simple cellular forms to complex organ systems, enhancing survival.

- Reproductive strategies, whether sexual or asexual, optimize species persistence, with some prioritizing frequent reproduction and others investing heavily in a single reproductive event.

These adaptations ensure survival in diverse ecosystems.

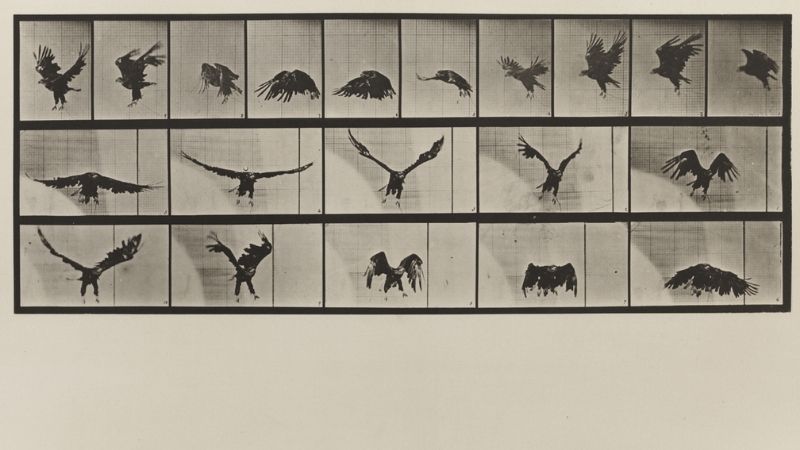

Locomotion

The locomotion of animals is classified based on their skeletal systems, including:

- Hydrostatic Skeleton-Based Movement

This system uses a fluid-filled cavity with opposing muscle layers, enabling movements like crawling, burrowing, and looping. Motion occurs through coordinated extension, attachment, release, and contraction. Segmented structures, as seen in earthworms, enhance control and efficiency.

- Elastic Skeleton-Based Movement

Elastic skeletons maintain shape while bending. Movement results from opposing muscle contractions or skeletal rebound. This system is prevalent in vertebrates, optimizing running, hopping, and climbing. During locomotion, tendons stretch to conserve energy, reducing muscle workload. For example, kangaroo tendons conserve about 54% of metabolic energy by recycling hopping energy.

- Rigid Jointed Skeleton-Based Movement

This system relies on rigid segments connected by flexible joints, functioning as levers for precise movement. It is optimized for power (short limbs, thick muscles) or speed (long limbs, slender muscles) and is highly effective in terrestrial environments.

Animals use diverse locomotion systems adapted to their environments. Annelids rely on segmented hydrostatic skeletons for burrowing. Arthropods and vertebrates, despite differing skeleton types, both use jointed systems for various movements like running, swimming, and flying.

Marine invertebrates, such as jellyfish and nematodes, utilize hydrostatic or elastic systems, often depending on water pressure. Evolution has shaped these mechanisms, optimizing movement efficiency and sometimes combining multiple systems for specialized functions.

Feeding and digestion

Animals use different locomotion and feeding strategies based on energy efficiency and environmental factors.

- Sessile feeders remain stationary, relying on environmental conditions to bring food. Common in aquatic environments, they develop defensive adaptations and radial symmetry but require mobility for reproduction.

- Burrowing animals either consume organic-rich substrates or use burrows for protection while filtering food. Some even live inside other organisms for shelter and sustenance.

- Active foragers move to find concentrated food sources, leading to evolutionary arms races between predators and prey.

- Cooperative feeders work within or across species, like ants farming fungi or cleaner fish removing parasites.

Digestion has also evolved to support these feeding strategies. Primitive animals use intracellular digestion, suitable for small food particles. More advanced species employ extracellular digestion, breaking down food in specialized digestive tracts.

The one-way gut enables efficient nutrient extraction, with adaptations like stomach storage and microbial fermentation aiding digestion.

Some animals, like spiders and starfish, use external digestion, breaking down food outside their bodies. Surface area optimization, including gut branching and microvilli, enhances absorption, with herbivores typically having longer intestines than carnivores.

These adaptations illustrate how movement and digestion have co-evolved, enabling animals to efficiently acquire and process nutrients while adapting to their specific ecological niches.

Sensory systems

Animals rely on diverse sensory systems to interpret their surroundings.

- Vision converts light into neural signals, ranging from basic light detection in simple organisms to advanced color vision in complex species. Some animals perceive ultraviolet, polarized light, or infrared.

- Chemoreception, responsible for smell and taste, recognizes molecules through receptor sites, triggering neural impulses that the brain deciphers.

- Sound detection relies on mechanoreceptors, with vertebrates using lateral-line systems in water and ear structures on land. Echolocation in bats and whales exemplifies specialized adaptations.

- Touch and mechanoreception respond to pressure, stretching, and gravity, functioning across all animals, even sponges. Sensory systems convert stimuli into neural signals, with brain processing playing a vital role.

Many species possess enhanced senses beyond human perception, often integrating multiple systems for survival. These adaptations illustrate the evolutionary refinement of sensory mechanisms to meet specific ecological needs.

Structural organization & adaptations

Animals exhibit four main levels of structural organization: cellular, tissue, organ, and organ system levels, reflecting their evolutionary progression from simple to complex organisms.

- At the cellular level, animals like sponges (Porifera) consist of loosely arranged, independent cells without true tissues. These cells coordinate essential functions such as feeding and excretion.

- The tissue level, seen in cnidarians like jellyfish and corals, features specialized tissues that perform distinct functions but lack true organs. These animals possess a nerve net for basic coordination and use specialized stinging cells to capture prey.

- The organ level appears in flatworms (Platyhelminthes), where tissues form organs such as a simple digestive system with a single opening and a ladder-like nervous system. Though more advanced, they still lack fully developed organ systems.

- The organ system level, found in mollusks, arthropods, and vertebrates, includes highly specialized systems for digestion, circulation, respiration, and excretion. Vertebrates have advanced nervous systems, with mammals exhibiting the most developed brains.

These structural adaptations allow animals to efficiently interact with their environment, obtain food, escape predators, and reproduce. From simple cellular coordination to complex organ systems, these evolutionary advancements support survival across diverse ecosystems.

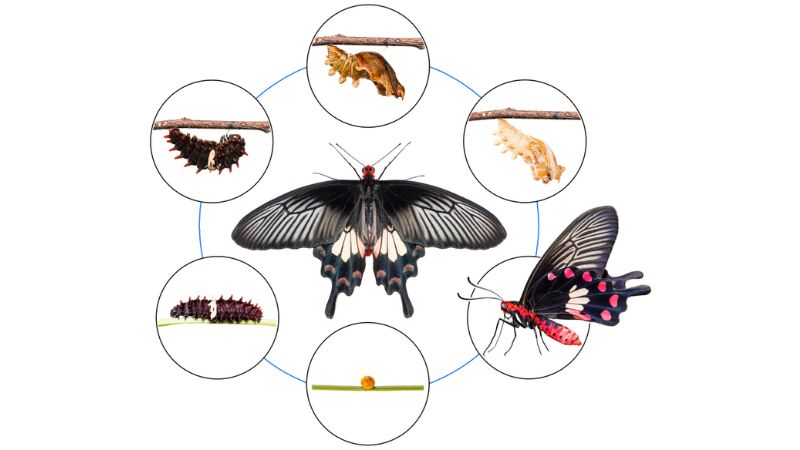

Reproduction and life cycles

Overview of sexual and asexual reproduction:

Reproduction encompasses sexual and asexual strategies.

- Sexual reproduction is a biological process in which two parents contribute genetic material to produce offspring. It involves the fusion of male and female gametes (sperm and egg), resulting in genetically diverse offspring.

- Asexual reproduction is a biological process where a single parent produces offspring without the involvement of gametes or another parent. The offspring are genetically identical clones of the parent.

Here is a comparison table between sexual reproduction and asexual reproduction in animals:

| Aspect | Sexual Reproduction | Asexual Reproduction |

| Definition | Involves two parents combining genetic material to produce offspring. | Involves a single parent producing genetically identical offspring. |

| Genetic Variation | High genetic variation due to the combination of genes from two parents. | No genetic variation; offspring are clones of the parent. |

| Process | Involves gametes (sperm and egg cells) and fertilization. | Involves mitosis or other processes like budding, fission, or regeneration. |

| Energy Requirement | High, due to mate finding, courtship, and gamete production. | Low, as it doesn’t require mating or specialized reproductive structures. |

| Speed of Reproduction | Slow, as it depends on the availability of mates and gestation periods. | Fast, allowing rapid reproduction in favorable conditions. |

| Adaptation Potential | High, as genetic variation aids in adaptation to changing environments. | Low, making the species more vulnerable to environmental changes. |

| Examples in Animals | Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and some fish. | Starfish (regeneration), hydras (budding), and some flatworms (fission). |

| Advantages | Greater genetic diversity, leading to stronger populations over time. | Rapid population growth and low energy expenditure. |

| Disadvantages | Time and energy-intensive; fewer offspring in a given time. | No genetic diversity, increasing susceptibility to diseases and environmental changes. |

Examples of reproductive strategies and their adaptive advantages:

Animals employ diverse reproductive strategies. Iteroparity yields multiple offspring over time, balancing investment and quantity. Semelparity focuses on a single, intense reproductive event, advantageous in unpredictable environments. Parental care enhances offspring survival, showcasing the complexity of reproductive adaptations in various environments.

What Threats Do Animals Face?

Animals worldwide face numerous threats that endanger biodiversity and disrupt ecosystems. Habitat loss due to deforestation, urban expansion, and wetland destruction forces species like orangutans, tigers, and amphibians out of their natural environments.

Climate change accelerates polar ice melt, alters migration patterns, and leads to coral bleaching, affecting species from polar bears to marine life.

Pollution poses severe risks, with plastic waste harming marine animals, chemical spills poisoning water sources, and air pollution damaging ecosystems.

Overexploitation through poaching, overfishing, and illegal wildlife trade threatens species such as elephants, sharks, and exotic pets. Invasive species outcompete native wildlife, disrupt food chains, and spread diseases, as seen with Burmese pythons in Florida.

Expanding human populations increase human-wildlife conflicts, leading to retaliatory killings when animals raid crops, prey on livestock, or enter urban areas.

Disease outbreaks like rabies and chytrid fungus devastate populations, while loss of genetic diversity weakens species’ resilience, as seen in Florida panthers. These challenges highlight the urgent need for conservation efforts to protect global wildlife.

By raising awareness, advocating for conservation policies, supporting sustainable practices, and participating in habitat restoration initiatives, individuals can help preserve wildlife and mitigate the detrimental effects of human activities.

Collaborative efforts between governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), local communities, and the private sector are essential in addressing the root causes of species decline and fostering a harmonious relationship between humans and the natural world.

FAQs

How do animal adaptations evolve?

Animal adaptations evolve through natural selection, where advantageous traits that enhance survival and reproduction become more prevalent in a population over time.

What are some examples of locomotion in animals?

Examples of locomotion in animals include walking, running, swimming, flying, hopping, and slithering, each adapted to the specific needs and environments of different species.

What is the significance of circulation and transport systems in animals?

Circulation and transport systems in animals are significant for distributing nutrients, oxygen, hormones, and waste products throughout the body and maintaining physiological equilibrium.

Discover more with Animal Pedia and uncover the extraordinary diversity of the animal kingdom and its role in shaping life on Earth!