What are invertebrates?

Invertebrates are animals that don’t have a backbone or a spine. They come in a wide range of shapes, sizes, and colors. From tiny insects to beautiful seashells, invertebrates can be found everywhere. They play essential roles in nature, like pollinating flowers, decomposing waste, and being vital to food chains. Invertebrates are incredibly diverse, with countless species that have adapted to survive in different environments.

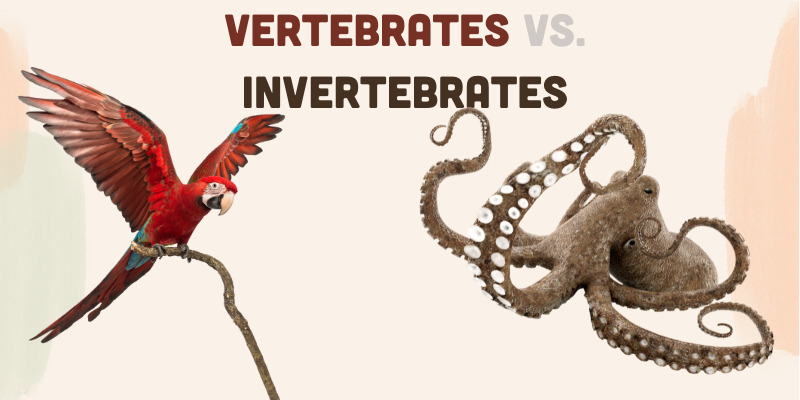

How are Invertebrates Different from Vertebrates?

Vertebrates are animals that have a backbone or vertebral column. This characteristic structure comprises bones called vertebrae, which protect and support the spinal cord. Vertebrates include familiar animals such as mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish.

In contrast, invertebrates are animals that do not have a backbone. They lack the vertebral column found in vertebrates. Invertebrates comprise most animal species and cover many organisms, including insects, spiders, worms, mollusks, crustaceans, and many more.

| Characteristic | Vertebrates | Invertebrates |

| Presence of Backbone | Yes | No |

| Examples | Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish | Insects, spiders, worms, mollusks, jellyfish |

| Body Symmetry | Bilateral | May vary (e.g., radial, bilateral) |

| Nervous System | Dorsal nerve cord | Ventral nerve cord |

| Reproduction | Mostly sexual | Both sexual and asexual |

| Size Range | Range from tiny to massive | Range from tiny to massive |

| Habitat | Terrestrial, aquatic, aerial | Terrestrial, aquatic, aerial |

| Respiratory System | Lungs, gills, skin | Gills, tracheae, diffusion through skin |

| Circulatory System | Closed system with a heart | Open system with hemolymph |

| Exoskeleton | Absent | Present in some groups (e.g arthropods) |

| Examples of Groups | Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians. fish | Insects, arachnids, annelids, mollusks |

Classifying animals into vertebrates and invertebrates highlights the vast diversity of invertebrates and their ecological significance. Vertebrates, defined by their backbone, share evolutionary traits and often occupy higher trophic levels as predators or herbivores. In contrast, invertebrates play vital roles as pollinators, decomposers, and primary consumers. This distinction aids scientists in studying evolutionary relationships, adaptation patterns, and ecosystem interactions, enhancing our understanding of biodiversity and animal functions across habitats.

Which characteristics do make Invertebrates unique?

Morphology and Symmetry

Invertebrates exhibit a diverse range of body symmetries. Some invertebrates, such as jellyfish and sea anemones, display radial symmetry. Their bodies are organized around a central axis, allowing multiple planes to divide them into similar halves. Many invertebrates possess bilateral symmetry, where their bodies can be divided into two halves along a single plane. This symmetry enables distinct front and back ends and a clear distinction between the top and bottom sides.

Examples of Symmetric Invertebrates:

- Gastropods: Gastropods like snails and slugs exhibit bilateral symmetry. Their bodies can be divided into similar halves along a central plane.

- Crustaceans: Crustaceans, including crabs and lobsters, also demonstrate bilateral symmetry. Their body structures, such as the arrangement of limbs, display a mirrored pattern on both sides.

Examples of Asymmetric Invertebrates:

- Sessile Animals: Sessile invertebrates like sponges and coral colonies lack apparent symmetry. Their body forms are irregular and do not exhibit any specific symmetry pattern.

- Sea Urchins: Sea urchins are echinoderms that typically possess pentaradial symmetry as adults. However, their larval stage, called pluteus larvae, is asymmetric.

- Sea Stars (Starfish): Most sea stars display pentaradial symmetry as adults, with their bodies organized around five arms. However, some species of sea stars may exhibit variations in the number of arms and display asymmetry.

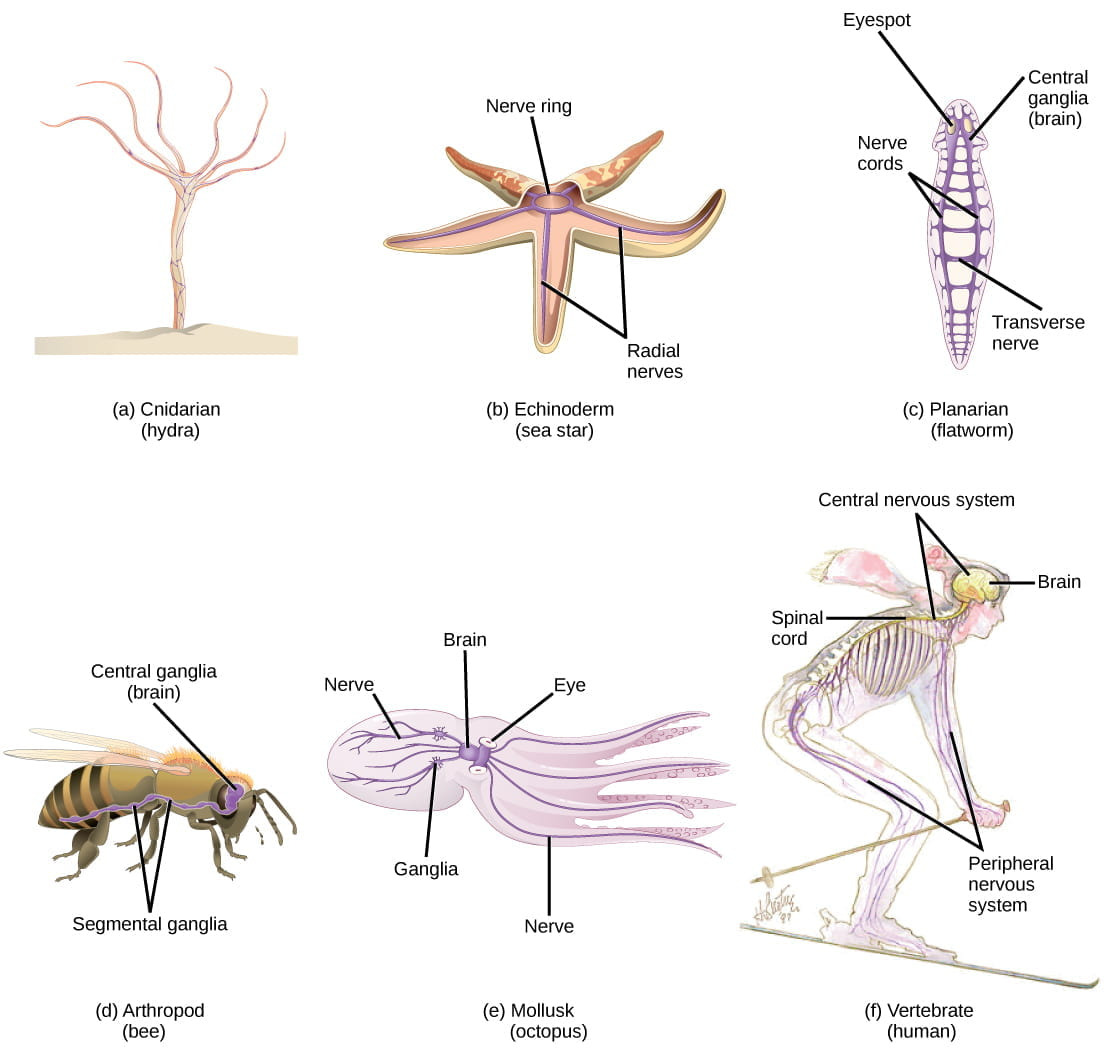

Nervous System

Invertebrate nervous systems, though simpler in structure, are highly adaptive, enabling them to perceive and respond to their environments. These systems typically consist of decentralized networks of ganglia that control sensory and motor functions, suited to the specific ecological roles of invertebrates. For example, species like the fruit fly, nematode worm, sea slug, and honeybee serve as model organisms, offering insights into neural development and behavior.

In contrast, vertebrates possess a centralized nervous system with a brain and spinal cord, offering more intricate processing and higher-order functions. Mammalian neurons, for instance, have more complex branching and synaptic connections compared to invertebrate neurons, allowing advanced behaviors like problem-solving and learning.

Both groups rely on electrical signals (action potentials) and neurotransmitters for communication, but invertebrate systems are less specialized, reflecting their evolutionary simplicity. Despite this, invertebrates like fruit flies, roundworms, and honeybees have been key models in neuroscience, shedding light on learning, memory, and behavior.

While vertebrates exhibit complex cognition and behavior, invertebrates demonstrate diverse adaptive capabilities with forms of learning such as habituation, conditioning, and spatial memory, highlighting the evolutionary ingenuity of their simpler nervous systems.

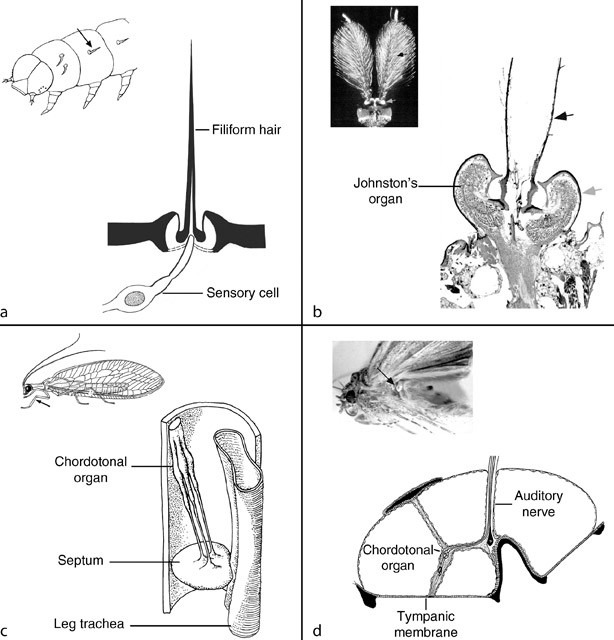

Hearing

Invertebrates have developed unique adaptations for detecting sounds, enabling them to perceive auditory cues and navigate their environment. Unlike vertebrates, which rely on complex auditory organs like ears, invertebrates use specialized structures such as tympanal organs in insects, subgenual organs in spiders, and setae (bristles) in caterpillars. These structures are sensitive to vibrations and sound waves, helping invertebrates detect distant and near-field sounds, such as mating calls, predator warnings, or prey movements.

In contrast, vertebrates possess a more centralized and advanced auditory system, typically involving external, middle, and inner ear components. Vertebrate hearing is highly specialized, with organs like the cochlea in mammals enabling detailed frequency discrimination and sound localization. This complexity allows vertebrates to process a broader range of auditory information compared to invertebrates.

While vertebrates rely on internalized organs for sound processing, invertebrates often depend on external sensory adaptations, reflecting the diverse evolutionary strategies between the two groups. Both systems, however, serve critical roles in survival and environmental interaction.

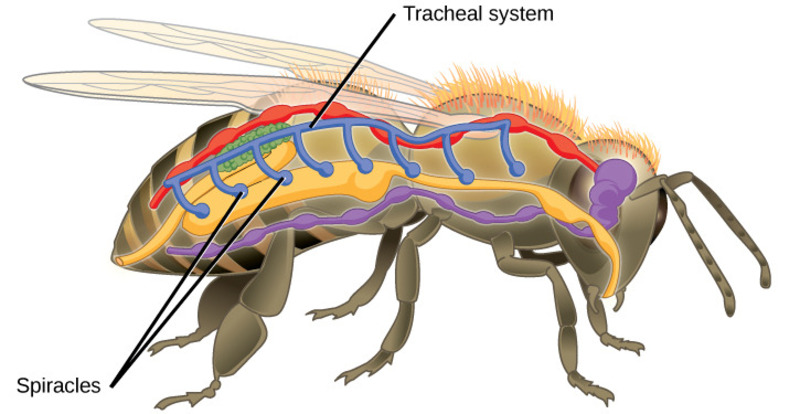

Respiratory System

Many invertebrates, such as terrestrial arthropods, utilize a tracheal system for respiration. This system consists of spiracles (external openings) that connect to a network of tracheae and tracheoles. Oxygen diffuses directly to cells without requiring a centralized organ. Aquatic invertebrates adapt with gills, plastron respiration, or cutaneous respiration to extract oxygen from water. These methods emphasize simplicity and direct gas exchange mechanisms.

On the other hand, vertebrates rely on centralized respiratory organs, such as lungs or gills, where gas exchange occurs within specialized structures like alveoli or lamellae. The circulatory system then transports oxygen throughout the body.

The tracheal system in invertebrates provides direct oxygen delivery, avoiding the need for blood-based transport. Vertebrates, however, depend on complex organ systems and circulatory processes, which allow for larger body sizes and higher metabolic rates.

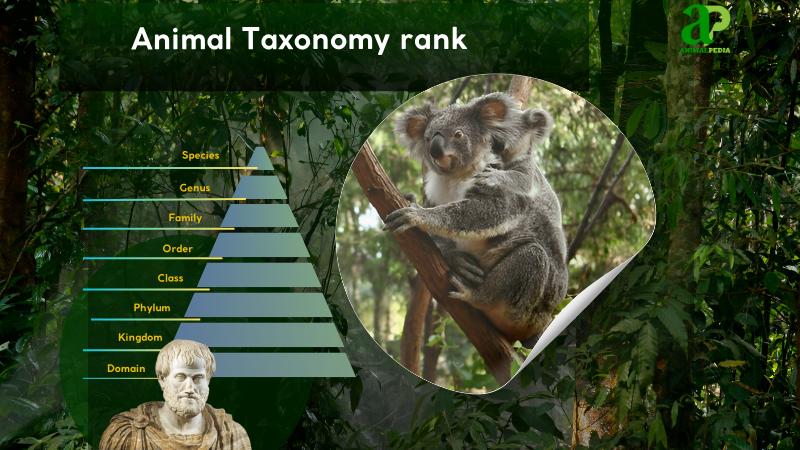

Classification

Invertebrates are classified into approximately 30 phyla. The number may vary slightly depending on the classification system used and how scientists interpret the evolutionary relationships among certain groups. The main phyla mentioned earlier, such as Porifera, Cnidaria, Platyhelminthes, Nematoda, Annelida, Mollusca, Arthropoda, Echinodermata, and others, form a significant part of this total.

The table below outlines the classification of invertebrates, showcasing their diversity and ecological significance. In addition to invertebrates, understanding the classification of vertebrates, such as fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds, is essential for comprehensively studying ecosystems. Specifically, exploring the birds classification and types can reveal important insights into avian adaptations and their roles within various habitats. Additionally, investigating mammals and their unique characteristics can provide a deeper understanding of their adaptive strategies to different environments. By examining the evolutionary relationships among vertebrate groups, researchers can identify key traits that enable survival and reproduction in diverse ecological niches. This holistic approach to studying both invertebrates and vertebrates fosters a greater appreciation for the intricate web of life and the interdependencies that sustain ecosystems around the globe. This exploration extends to the classification of amphibians, which serve as crucial indicators of environmental health due to their sensitivity to changes in ecosystem dynamics. By examining an amphibian species detailed overview, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of their life cycles, developmental stages, and the impact of habitat loss on their populations. Ultimately, studying both invertebrates and vertebrates fosters a more holistic approach to conservation efforts and biodiversity preservation. Furthermore, each group of vertebrates possesses unique adaptations that enable them to thrive in their respective environments. For example, a deeper exploration of the fish definition and characteristics can enhance our understanding of aquatic ecosystems and the myriad species that inhabit them. By examining these classifications, we can gain a holistic view of biodiversity and the intricate relationships that sustain life on Earth.

| Characteristics | Number of species | |

| Porifera (Sponges) | Simple multicellular organisms with porous bodies. They lack true tissues and organs. | Over 9,000 identified species |

| Cnidaria (Jellyfish, Corals, Sea Anemones) | Radially symmetrical animals with specialized stinging cells called cnidocytes. They have two distinct body forms: polyps (sessile) and medusae (free-swimming). | Approximately 11,000 identified species. |

| Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) | Soft-bodied, flattened worms with bilateral symmetry. Some are free-living, while others are parasitic. | Around 25,000 identified species. |

| Nematoda (Roundworms) | Unsegmented worms with cylindrical bodies and tapered ends. They are found in diverse habitats, including soil, freshwater, and marine environments. | Estimated to be over 25,000 identified species |

| Annelida (Segmented Worms) | Segmented worms with a true coelom (body cavity) and distinct repeating body segments. They can be found in various habitats, including marine, freshwater, and terrestrial environments. | Approximately 22,000 identified species. |

| Arthropoda (Insects, Crustaceans, Arachnids) | The largest phylum of invertebrates, characterized by a segmented body, jointed appendages, and an exoskeleton made of chitin. It includes insects, spiders, crustaceans, and more. | Over one million identified species. |

| Mollusca (Snails, Clams, Squids) | Soft-bodied animals are often protected by a hard shell. They have a muscular foot and a visceral mass containing internal organs. | Around 85,000 identified species. |

| Echinodermata (Starfish, Sea Urchins, Sea Cucumbers) | Radially symmetrical marine animals with a spiny exoskeleton. They have a unique water vascular system used for locomotion and feeding. | Approximately 7,000 identified species. |

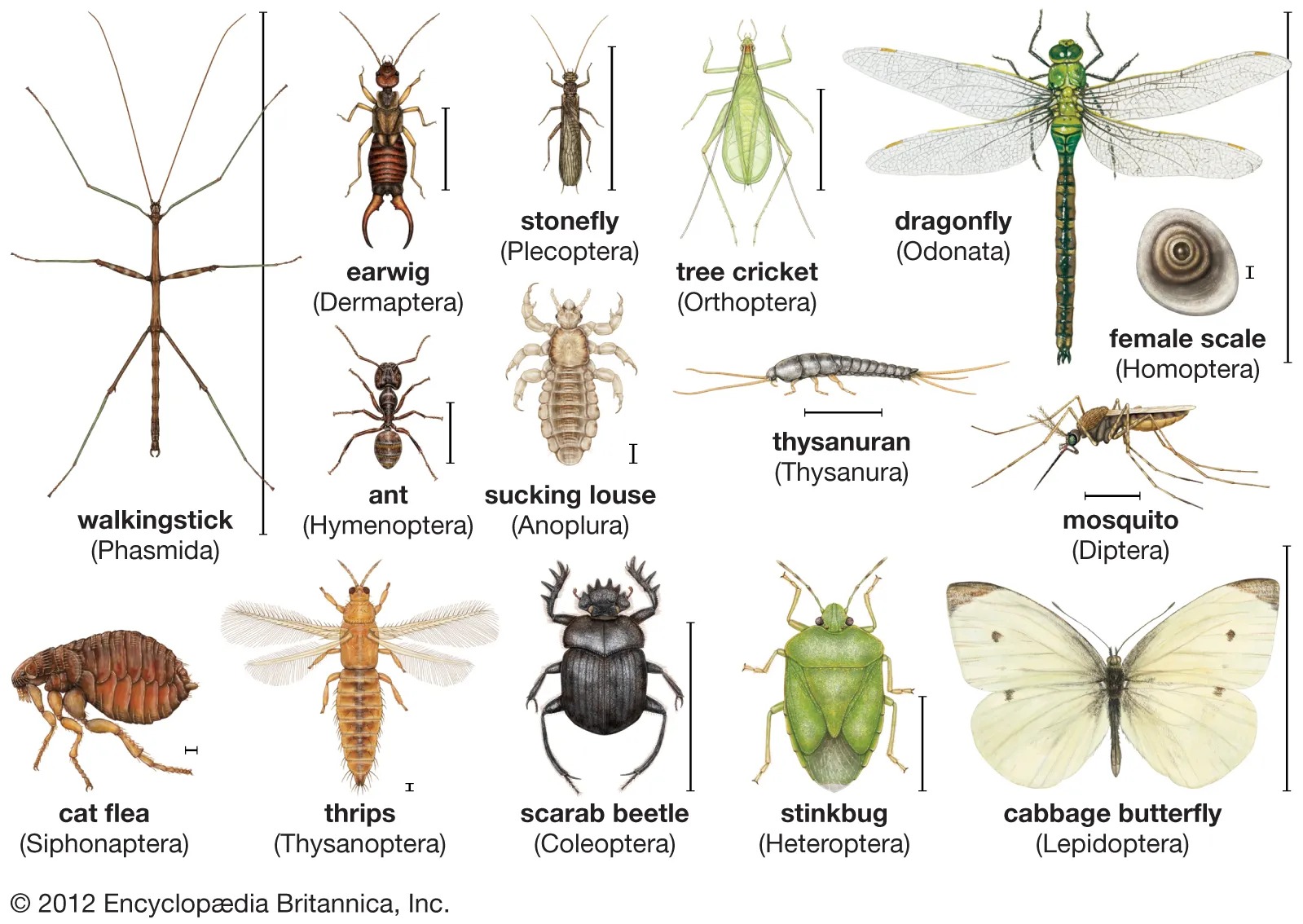

Arthropods

Arthropods are a vast and diverse phylum of invertebrate animals, representing the largest group within the animal kingdom in terms of species diversity and abundance. Found in nearly all habitats—land, freshwater, and marine environments—arthropods play essential roles in ecosystems and human life.

2 Characteristics of Arthropods:

- Exoskeleton: Made of chitin, providing protection, support, and a surface for muscle attachment. Arthropods molt their exoskeleton as they grow.

- Segmented Body and Jointed Appendages: Their body is divided into segments (e.g., head, thorax, abdomen), each typically with jointed appendages adapted for functions like movement, feeding, or sensing the environment.

There are three main subgroups of Arthropods

- Insects

- Most diverse arthropod group with over a million identified species.

- Body divided into three segments: head, thorax, and abdomen, with six legs.

- Ecological roles: pollination, decomposition, predation, and serving as prey.

- Examples: beetles, butterflies, ants, bees, flies.

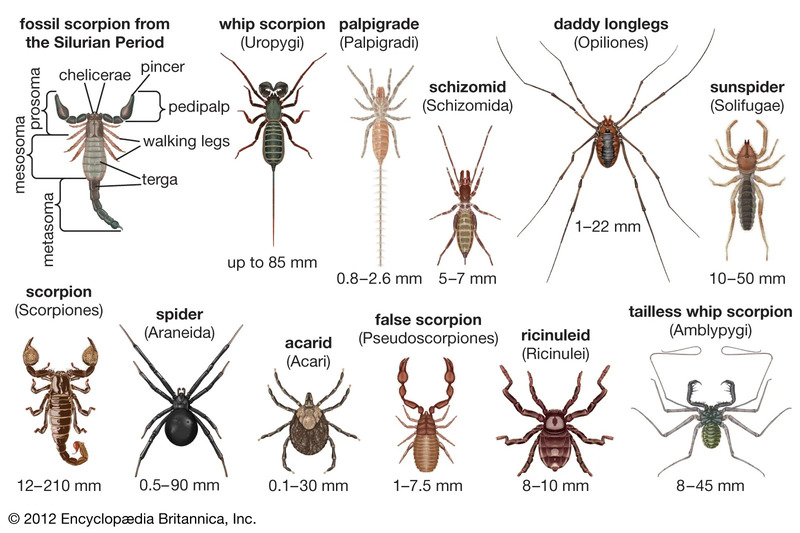

- Arachnids

- Characterized by two body segments: cephalothorax and abdomen, with eight legs.

- Primarily terrestrial, often predators or nutrient cyclers.

- Examples: spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites.

- Crustaceans

- Predominantly aquatic, with segmented bodies and a hard exoskeleton.

- Possess two pairs of antennae and specialized appendages for various functions.

- Examples: crabs, lobsters, shrimp, barnacles.

Arthropods’ ecological and economic significance cannot be overstated, as they contribute to pollination, pest control, and serve as a food source. Moreover, their role in industries like beekeeping and silk production highlights their profound impact on human societies.

Mollusks

Mollusks are a fascinating and diverse group of invertebrate animals characterized by their soft bodies, often enclosed within a calcium carbonate shell. They inhabit various environments, from deep oceans to freshwater systems and even terrestrial landscapes. Mollusks are known for their ecological significance, economic value, and structural diversity.

3 Key Characteristics of Mollusks:

- Soft Body with Shell: While many mollusks have a protective external shell, others have internal or absent shells. Their bodies house essential systems like digestion and reproduction.

- Muscular Foot: This structure is adapted for movement or attachment, varying in shape across species.

- Radula: Many mollusks possess this specialized tongue-like organ for scraping or rasping food.

There are 4 main subgroups of Mollusks

1. Gastropods

-

- The largest subgroup, including snails and slugs.

- Typically have a single spiral shell (except slugs).

- Found in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial habitats.

- Examples: Garden snail, sea hare.

2. Bivalves

-

- Characterized by two hinged shells.

- Filter feeders with specialized gills.

- Mostly aquatic, they include species like clams, mussels, and scallops.

- Examples: Blue mussel, giant clam.

3. Cephalopods

-

- Known for intelligence and advanced sensory organs.

- Have tentacles and may possess an internal shell (like squids) or none (like octopuses).

- Examples: Octopus, squid, cuttlefish.

4. Polyplacophorans (Chitons)

-

- Marine species with oval, flattened bodies and a shell composed of eight plates.

- Examples: Gumboot chiton.

Mollusks play critical roles in ecosystems, from recycling nutrients to serving as a food source for numerous organisms. Economically, they are integral to fisheries, aquaculture, and industries like pearl production.

Annelids

Annelids, commonly referred to as segmented worms, are a diverse group of invertebrates characterized by their distinct body segmentation. Found in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial habitats, they play crucial roles in nutrient cycling, soil health, and organic matter decomposition. 2 Key traits of annelids include:

- Segmented Body: Each segment (metamere) has specialized organs, enhancing flexibility and mobility.

- Hydrostatic Skeleton: A fluid-filled coelom supports movement and functions as a basic circulatory system.

There are two main subgroups of Annelids

1. Oligochaetes

-

- Examples: Earthworms.

- Habitat: Primarily terrestrial or freshwater.

- Role: Aerating soil, decomposing organic matter, and enhancing soil fertility.

2. Polychaetes

-

- Examples: Ragworms, bristle worms.

- Habitat: Mainly marine; some in freshwater or terrestrial zones.

- Role: Act as filter feeders, scavengers, and predators in marine ecosystems.

Annelids significantly impact ecosystems and scientific studies, from soil engineering by earthworms to the medical applications of leeches. They illustrate the importance of segmentation and adaptability in various environments.

Echinoderms

Echinoderms are a diverse group of marine invertebrates that share unique characteristics, including radial symmetry in adulthood, spiny skin, a water vascular system, and tube feet. These features enable echinoderms to adapt well to their marine environments, making them ecologically significant in the oceans. They are found worldwide and play vital roles in marine ecosystems.

2 Key characteristics of echinoderms:

- Radial Symmetry: Adult echinoderms exhibit radial symmetry, with body parts arranged around a central axis, which helps them interact with their surroundings from all directions. In contrast, their larvae have bilateral symmetry.

- Water Vascular System: This unique system consists of fluid-filled canals and tube feet, enabling locomotion, feeding, and gas exchange by using hydraulic pressure to extend and retract the tube feet.

2 Subgroups of echinoderms:

- Asteroidea (Starfish/Sea Stars):

- Central disk with radiating arms.

- Use tube feet for locomotion and prey capture.

- Example: Asterias rubens (Common starfish).

- Echinoidea (Sea Urchins, Sand Dollars, and Biscuits):

- Rounded or flattened body with a hard, spiny shell (test).

- Sea urchins have long spines, sand dollars are flat and burrow in sand.

- Example: Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (Purple sea urchin), Clypeasteroida (Sand dollars).

Echinoderms are essential for maintaining the balance in marine ecosystems by serving as both predators and prey, contributing to nutrient cycling, and helping to stabilize sediments. Some species also hold commercial value, like sea cucumbers, which are harvested for food and medicinal use.

Cnidarians

Cnidarians are a phylum of invertebrate animals that include jellyfish, corals, sea anemones, and the Portuguese man o’ war. Known for their diverse body forms and distinctive features, cnidarians are recognized for having specialized stinging cells called cnidocytes. These animals exhibit a range of lifestyles and are found in marine environments across the globe.

2 Key characteristics of cnidarians:

- Cnidocytes: Specialized cells containing nematocysts, which are used for defense and capturing prey. These cells discharge a barbed thread when triggered, injecting venom into the target organism.

- Two Body Forms: Cnidarians have two primary body forms: the polyp and the medusa. Polyps are usually cylindrical and sessile (attached to a substrate), while medusas are bell-shaped and free-swimming. The polyp form is linked to asexual reproduction, while the medusa form is associated with sexual reproduction and mobility.

2 Subgroups of cnidarians:

- Hydrozoa:

- Includes species like the Portuguese man o’ war.

- Exhibits both polyp and medusa stages in their lifecycle.

- Polyps are often colonial, sharing a common gastrovascular cavity, while medusas are free-swimming with bell-shaped bodies.

- Scyphozoa:

- Known as the true jellyfish.

- Medusa form is dominant, often with a bell-shaped body and long tentacles equipped with cnidocytes.

- Capable of movement via rhythmic pulsations of their bell.

Cnidarians play crucial roles in marine ecosystems. They serve as a food source for various organisms, participate in nutrient cycling, and are essential to coral reef ecosystems. Corals, in particular, contribute to the formation of some of the planet’s most diverse and productive habitats. However, some cnidarians, such as jellyfish, can undergo population explosions, known as blooms, which can disrupt local ecosystems and human activities.

Importance of Invertebrates to Humans

Invertebrates play a vital role in both maintaining the balance of ecosystems and benefiting human activities. Their contributions are far-reaching, supporting the environment, agriculture, medicine, and culture. Below are the key ecological roles and the benefits they provide to humans.

Ecological Roles of Invertebrates

Invertebrates are essential for various ecological services that help maintain healthy ecosystems:

- Pollination: Insects like bees and butterflies are crucial pollinators, ensuring the reproduction of many plants and crops.

- Decomposition: Earthworms, beetles, and other detritivores break down organic matter, recycling nutrients back into the soil, enhancing its fertility and structure.

- Nutrient Cycling: Invertebrates help in nutrient cycling by mixing organic material with soil particles, improving soil aeration and water retention.

- Pest Control: Predatory insects naturally control pest populations, reducing the need for chemical pesticides in agriculture.

- Food Source: Invertebrates serve as a primary food source for many vertebrates, supporting higher trophic levels in ecosystems.

Benefits to Humans

In addition to their ecological roles, invertebrates provide direct benefits to humans, enhancing agricultural productivity, medicine, and cultural value:

- Agricultural Productivity: Pollination by insects is essential for about one-third of the food we consume, making invertebrates economically important for farming.

- Soil Health Improvement: Earthworms improve soil structure and water infiltration, boosting crop yields and promoting sustainable farming practices.

- Medicinal Resources: Marine invertebrates offer bioactive compounds with antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, contributing to drug development.

- Cultural and Aesthetic Value: Invertebrates play roles in recreational activities like bird watching and fishing, contributing to tourism and cultural activities.

In summary, invertebrates are indispensable for both natural ecosystems and human welfare. Their diverse roles in pollination, decomposition, nutrient cycling, and as resources for human use underscore their immense value in supporting ecological health and economic productivity.

Evolution and history

The evolution of invertebrates spans hundreds of millions of years, from simple sponges to complex arthropods and mollusks:

- Late Ediacaran Period (635-541 million years ago): The earliest fossils of multicellular life, showcasing the first signs of complex invertebrates.

- Cambrian Explosion (541 million years ago): A rapid diversification of invertebrate life, with the emergence of major groups like trilobites, brachiopods, mollusks, and arthropods.

- 2020 Discovery in South Australia: Fossils from the Trezona Formation, including Tappania and Dickinsonia, indicate sponge-like invertebrates existed 665 million years ago, earlier than previously thought.

- Ordovician Period (453 million years ago): The “Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event” marks a significant increase in invertebrate diversity, including brachiopods, trilobites, cephalopods, and bivalves.

Invertebrate fossils are often found in shale, limestone, and sandstone, each forming in different environments. Fossils like ammonites and trilobites play a crucial role in biostratigraphy, helping scientists date rock layers and develop geologic time scales.

How Invertebrates Survive and Thrive in Nature

Invertebrate behavior is crucial for survival, aiding in food acquisition, predator avoidance, reproduction, and ecosystem interactions. They display diverse foraging and reproductive behaviors, including courtship rituals and parental care. As pollinators, decomposers, predators, and prey, invertebrates significantly impact nutrient cycling, plant reproduction, and ecological balance.

Feeding Habits and Hunting Techniques

Invertebrates are fascinating creatures with different ways of finding and eating food. They have unique methods of moving and hunting, which help them survive in their environments. Let’s explore how invertebrates eat, how they move, and some examples of these amazing animals!

- Herbivory (Eating Plants)

Some invertebrates, like insects, snails, and sea stars, love eating plants. They have special tools in their mouths to help them eat leaves, algae, and other plant materials. Insects, for example, have strong jaws to chew plants, while snails have a ribbon-like structure called a radula to scrape leaves.

Insects can crawl on the ground or fly to find plants to eat. Snails move by sliding on their soft foot, and sea stars use their tube feet to slowly crawl along the sea floor.

- Predation (Hunting Other Animals)

Some invertebrates are hunters! These animals catch and eat other creatures. Spiders use their webs to trap prey, while praying mantises use their fast arms to catch insects. Other hunters, like marine snails, use a special tool called a radula to grab their food.

Spiders and mantises move by crawling, using their legs or arms to quickly catch their prey. Marine snails can slowly crawl or quickly zoom through the water using their foot.

- Filter-Feeding (Filtering Food from Water)

Some invertebrates, like clams, barnacles, and sponges, don’t hunt or eat plants. Instead, they filter tiny food particles from the water! They use special parts like gills or tentacles to collect food from the water.

While many filter-feeders like barnacles stay in one place, some, like clams, can move slowly to find better spots for filtering food from the water.

Defense Mechanisms for Survival

Invertebrates have developed a variety of defense mechanisms to protect themselves from predators, competition, and environmental stress. These strategies are vital for their survival and reproduction, helping them evade danger and increase their chances of survival.

- Chemical Defenses

Many invertebrates use chemical substances to defend themselves. These toxins or deterrents can harm predators or make them avoid the animal altogether.

-

- Insects: Beetles can release toxic chemicals from special glands, while some caterpillars have spines or hairs that contain irritating compounds.

- Mollusks: Sea hares and cone snails produce venom to paralyze predators.

- Cnidarians: Jellyfish and sea anemones have specialized cells called cnidocytes that release venomous barbs to defend themselves.

- Camouflage and Mimicry

Camouflage and mimicry help invertebrates blend into their surroundings or resemble other, more dangerous animals, keeping them safe from predators.

- Stick and Leaf Insects: These insects mimic sticks or leaves, making them nearly invisible to predators.

- Octopuses: Octopuses can change the color and texture of their skin, blending seamlessly into their environment to hide from predators or ambush prey.

- Physical Defenses

Invertebrates also use physical adaptations to protect themselves. These include hard shells, spines, and armor-like exoskeletons.

- Spines and Armor: Sea urchins have sharp spines that deter predators, while beetles have hard exoskeletons that protect them from attacks.

- Protective Structures: Mollusks like clams and snails have hard shells, and some have a door-like structure called an operculum to keep predators out.

In conclusion, invertebrates employ various defense strategies, including chemical defenses, camouflage, and physical adaptations, to survive in their environments. These mechanisms help them avoid predation and thrive in the wild.

Social Behaviors and Communication

Social interaction is an important aspect of the lives of many invertebrate species, enabling them to interact with each other, exchange information, establish positions, search for food sources, and maintain cooperation within groups. Here are some ways in which invertebrates communicate and exhibit social behavior:

Chemical Communication: Many invertebrates use chemical signals, such as pheromones, to communicate with others of their species. These chemical signals can convey information about mating availability, territory boundaries, alarm signals, or the presence of food sources. For example:

- Ants: Ants use pheromones to mark trails leading to food sources, allowing other colony members to follow the scent and locate the food.

- Bees: Bees release alarm pheromones when they perceive a threat, signaling other bees to act defensively.

Vibrational Communication: Some invertebrates communicate through vibrations or substrate-borne signals. They produce and detect vibrations to convey messages to other individuals nearby. Examples include:

- Spiders: Male spiders produce vibrational signals on their webs to attract females for mating. They create specific patterns and frequencies to communicate their species and sexual readiness.

- Crickets: Male crickets produce chirping sounds by rubbing their wings together. The frequency and pattern of the chirps can convey information about the male’s species, age, and mating fitness.

Visual Communication: Visual signals are used by many invertebrates to communicate with conspecifics or other species. These signals can be in the form of body movements, color changes, or specific body postures. For instance:

- Cuttlefish: Cuttlefish are known for their ability to change their body color and patterns rapidly. They use these visual displays to communicate with potential mates or to intimidate rivals.

- Fireflies: Fireflies emit light signals in a species-specific pattern to attract mates. The flashing patterns and timing help individuals recognize and locate potential partners.

Group Living and Cooperation:

Invertebrates also exhibit group living and cooperation, where individuals work together to achieve common goals. Examples include:

- Social Insects: Ants, bees, wasps, and termites are well-known for their complex social structures. They live in large colonies with specialized castes, such as workers, soldiers, and reproductive individuals. Cooperation within these colonies involves foraging, nest building, brood care, and defense.

- Coral Reefs: Many invertebrates, such as corals, sponges, and anemones, form interconnected communities in coral reefs. They cooperate in the mutual exchange of nutrients and provide shelter and protection for other species.

These are just a few examples of how invertebrates communicate and exhibit social behavior. The specific mechanisms and behaviors vary across species, reflecting their ecological adaptations and evolutionary history.

Reproduction of Invertebrates

Types of Reproduction

Invertebrates reproduce through asexual and sexual reproduction.

- Asexual reproduction does not require a mate. It includes methods like budding, fission, and regeneration. For example, Hydra reproduces through budding, where new individuals grow from the parent and later detach. Sea stars can reproduce by fission, splitting into parts that regenerate into new organisms. Crayfish can regenerate lost limbs, aiding their survival.

- Sexual reproduction involves the fusion of male and female gametes, ensuring genetic diversity. Snails, for instance, have separate sexes and reproduce through external fertilization in water. Earthworms are hermaphroditic, producing both eggs and sperm, and exchange sperm during mating. Fertilization can be external, like in sea urchins, or internal, as seen in earthworms, which allows for more controlled reproduction.

Asexual reproduction promotes rapid population growth, while sexual reproduction introduces genetic variety, enhancing the species’ ability to adapt and survive. Both methods are essential for the continued existence of invertebrate species.

Parental care

Parental care in invertebrates includes behaviors that improve offspring survival and development, such as:

- Nest Building: Spiders create webs or silk sacs to protect their eggs.

- Brooding: Porcelain crabs carry their eggs in specialized pouches.

- Sacrifice for Survival: Female octopuses guard their eggs, abstaining from feeding and often dying after the eggs hatch.

- Male Care: Male seahorses carry fertilized eggs in a brood pouch until they hatch.

- Protection from Predators: Limpets build nests to protect eggs from predators and desiccation.

Parental care requires significant energy, which can reduce future reproductive potential but greatly increases offspring survival chances. These behaviors vary by species, helping invertebrates thrive in their environments.

FAQs

What percentage of animals are insects?

It is estimated that insects represent the largest class of animals, accounting for approximately 80% of all known animal species. This means that insects constitute a substantial majority of the animal kingdom. Their incredible diversity and adaptability have allowed them to thrive in almost every terrestrial and freshwater habitat on Earth. From beetles and butterflies to ants and bees, insects play vital roles in various ecosystems as pollinators, decomposers, and food sources for other animals. Their abundance and ecological significance make them a crucial component of global biodiversity.

Do all invertebrates lack a backbone?

Yes, that’s correct. Invertebrates are characterized by the absence of a backbone, a defining feature of vertebrates. Invertebrates lack the vertebral column or spine that provides structural support and protects the spinal cord in vertebrate animals. Instead, invertebrates have a wide variety of body structures and support systems, such as an exoskeleton (as seen in arthropods), hydrostatic skeletons (as seen in some worms), or internal structural elements like shells (as seen in mollusks). Invertebrates represent most animal species on Earth and exhibit incredible diversity in their body plans and adaptations.

Is a jellyfish an invertebrate?

Yes, jellyfish are fascinating invertebrates classified under the cnidarian group, which also includes corals, gorgonians, and anemones. The defining feature of this group is their specialized stinging cells, used both to subdue prey and defend against threats. These cells deliver a powerful sting, highlighting the evolutionary ingenuity of cnidarians.

What are the largest and smallest invertebrates?

The ribbon worm holds the record for the longest invertebrate, reaching up to 180 feet. The giant squid is the longest known invertebrate at 59 feet, while the colossal squid is the heaviest, weighing over 1,000 pounds.

The smallest invertebrates are single-celled organisms like amoebas. Among multicellular invertebrates, the rotifer, or wheel animal, is one of the tiniest, measuring as small as 50 micrometers.

Which invertebrates are dangerous to humans?

5 invertebrates can be dangerous to humans:

- Mosquitoes: Vectors for diseases like malaria, dengue, and Zika virus, causing millions of deaths annually.

- Black Widow Spider: Its venom can cause severe pain and muscle spasms, much more toxic than a rattlesnake bite.

- Asian Giant Hornet: Known for its venomous sting, it can be fatal, especially to those allergic, and can attack in swarms.

- Scorpions: Some species, like the Arizona bark scorpion, have venomous stings that can be lethal and require immediate medical attention.

- Assassin Caterpillar (Lonomia obliqua): Its venom disrupts blood clotting, causing hemorrhaging and potentially death.