Taxonomy Definition Rank

Taxonomy is the branch of biology that deals with organisms’ classification, identification, and naming. The word taxonomy originates from the Greek words “taxis” (meaning arrangement or order) and “nomia” (meaning method or law). This term was introduced in the 18th century and is closely associated with the work of Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus, often regarded as the “Father of Modern Taxonomy.” Linnaeus developed the system of binomial nomenclature and hierarchical classification that serves as the foundation for categorizing and naming living organisms.

The classification (or categorization, organization, grouping) of organisms is based on their shared characteristics, including morphological, anatomical, physiological, genetic, and ecological traits. Taxonomists (classification specialists) use techniques and tools, such as comparative anatomy, molecular biology, and phylogenetic analysis, to determine the evolutionary relationships between different organisms and assign them to their appropriate taxonomic groups (classification levels).

One key aspect distinguishing taxonomy from other classification methods is its emphasis on evolutionary relationships. Taxonomists classify organisms based on their physical characteristics and consider their genetic and ancestral links. This approach allows for a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the connections between different organisms.

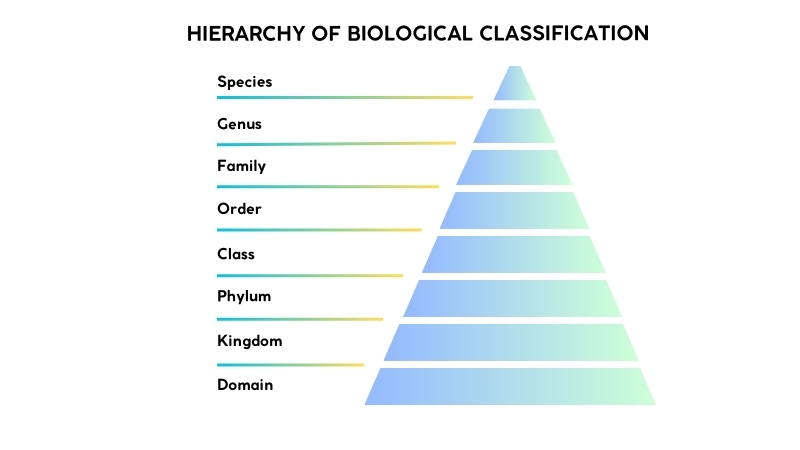

The taxonomic hierarchy organizes all living organisms into eight distinct classification levels. Here’s a concise overview:

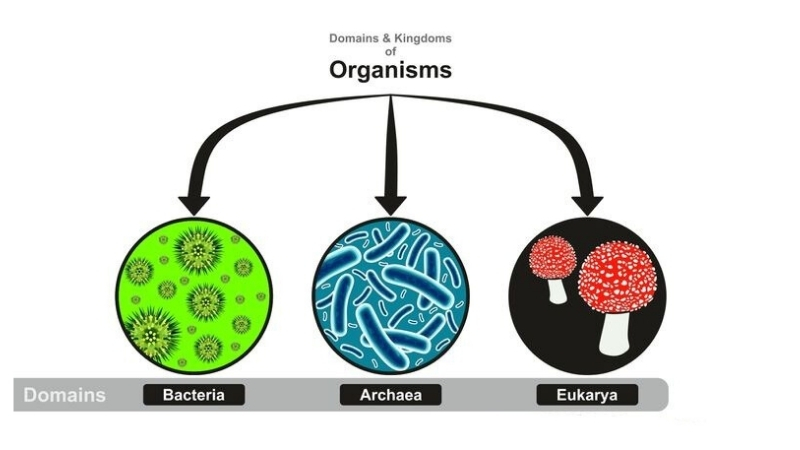

- Domain: The broadest category, dividing organisms into three groups: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya.

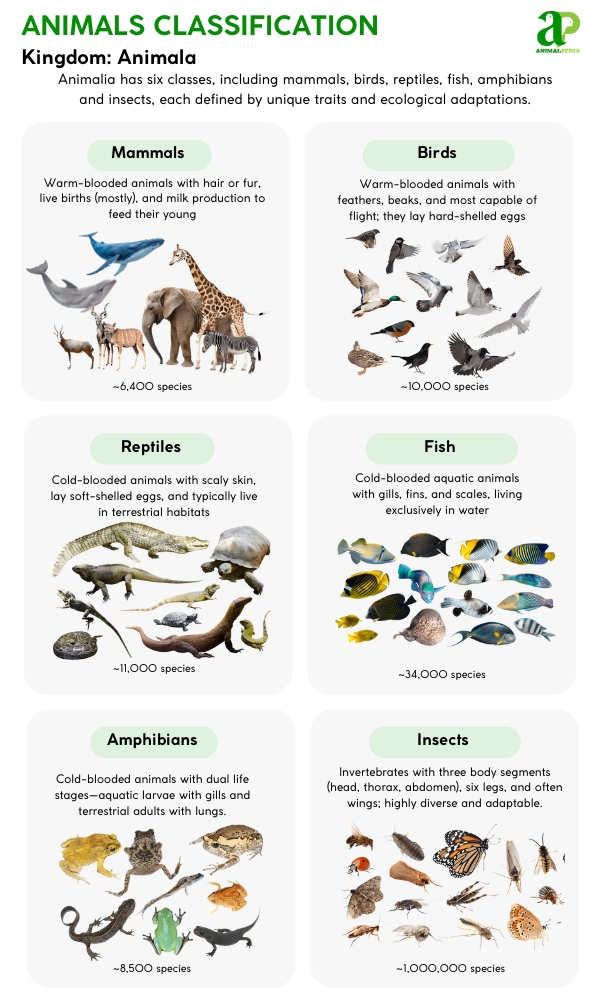

- Kingdom: Below the domain, this level groups organisms based on general traits. Examples include Animalia, Plantae, and Fungi.

- Phylum: Within kingdoms, phyla classify organisms with shared structural features, such as Chordata for vertebrates.

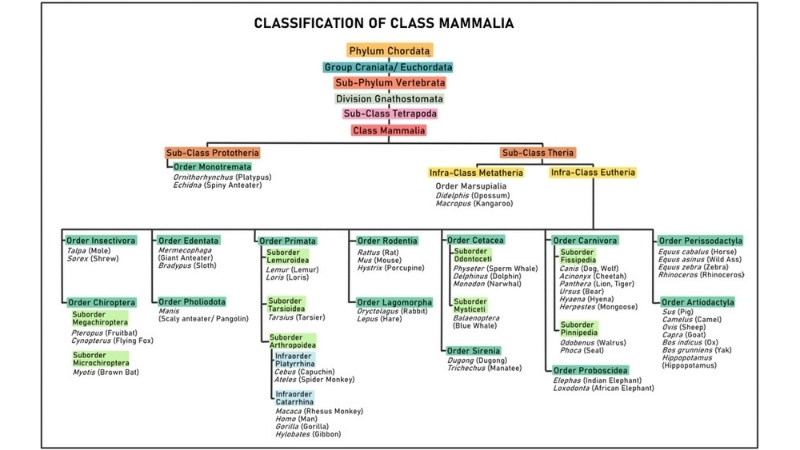

- Class: This category further divides phyla into groups like Mammalia (mammals) or Aves (birds).

- Order: Orders organize related families, such as Carnivora (carnivores) or Primates.

- Family: Families, like Felidae (cats) or Canidae (dogs), consist of related genera sharing key traits.

- Genus: A genus groups closely related species, such as Panthera, which includes lions and tigers.

- Species: The most specific level, defining organisms capable of interbreeding, like Homo sapiens for humans.

Benefits of Taxonomy

Taxonomy plays a vital role in systematic botany and zoology by establishing hierarchical arrangements of plants and animals. It provides a systematic framework for organizing and classifying the immense diversity of species, allowing scientists to categorize and identify organisms based on their shared characteristics precisely. By establishing hierarchical arrangements, taxonomy rank facilitates knowledge organization and enables researchers to study the relationships between species. It helps understand organisms’ evolutionary history and relatedness, crucial for evolutionary biology and phylogenetic studies.

Moreover, taxonomy is essential for conservation efforts and biodiversity assessments, allowing scientists to document and monitor species diversity. By providing a common language and reference system, taxonomy rank also fosters effective communication and collaboration among researchers in botany and zoology, promoting the advancement of scientific knowledge in these fields.

Distinguishing Taxonomist and Systematics

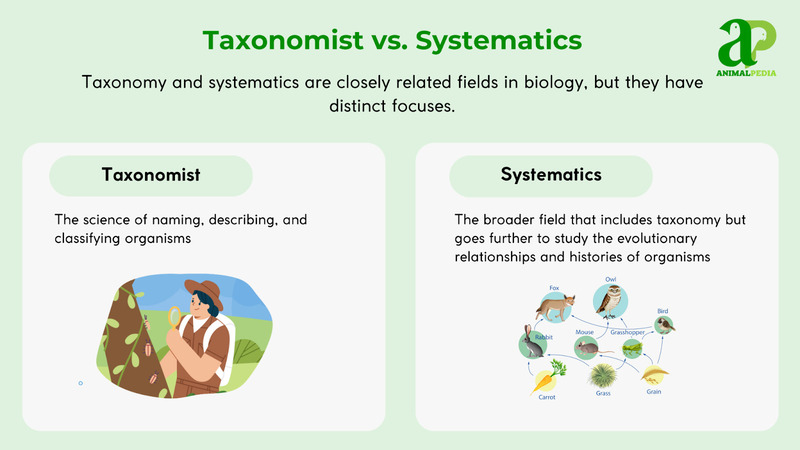

Taxonomy (organismal classification) focuses on identifying, naming, and organizing living things into hierarchical groups called taxon. It categorizes organisms based on morphological, anatomical, physiological, genetic, and behavioral traits to understand their relationships and assign them to appropriate classification levels. The taxonomic hierarchy has several levels, each representing a progressively narrower group of organisms.

From broadest to most specific, these levels are kingdom, phylum (animals) or division (plants & microorganisms), class, order, family, genus, and species. For example, humans belong to the kingdom Animalia, phylum Chordata, class Mammalia, order Primates, family Hominidae, genus Homo, and species Homo sapiens.

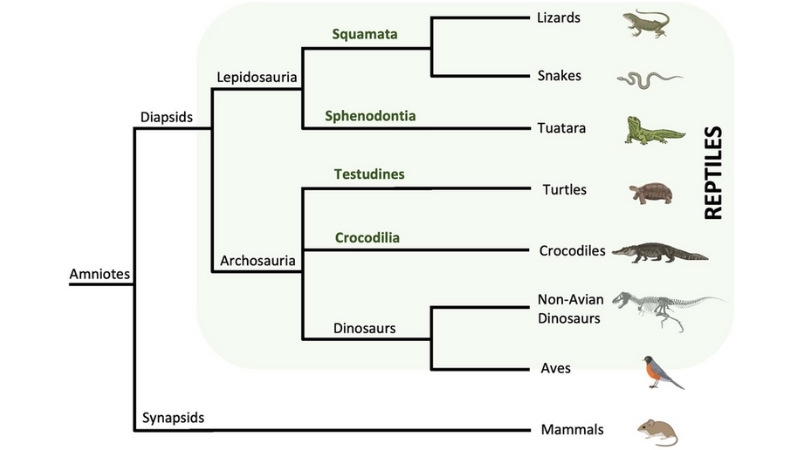

Systematics, on the other hand, is the broader field encompassing taxonomy. It delves deeper into evolutionary relationships among organisms and aims to reconstruct their evolutionary history and the tree of life. Systematists infer these evolutionary relationships using various data sources, including morphological, anatomical, molecular, and genetic information. They analyze similarities and differences in organismal characteristics and construct phylogenetic trees (cladograms) to determine their relatedness. These branching diagrams depict the evolutionary history of various lineages, showing their common ancestors and how they diverged over time.

| Aspect | Taxonomy | Systematics |

| Definition | Classifying and naming organisms based on shared characteristics. | Studying evolutionary relationships among organisms. |

| Focus | Categorizing organisms into hierarchical groups. | Understanding evolutionary history and relationships. |

| Purpose | Provides a standardized system for naming and organizing animals. | It aims to reconstruct the evolutionary history of animals. |

| Techniques | Uses morphological, anatomical, physiological, and genetic traits for classification. | Incorporates molecular data, phylogenetic analyses, and comparative morphology. |

| Application | Establishes a framework for biological classification. | It helps in understanding evolutionary relationships among animals. |

| Example | Classifying a lion (Panthera leo) into the kingdom Animalia, phylum Chordata, class Mammalia, order Carnivora, family Felidae, genus Panthera, and species Panthera leo. | Analyzing DNA sequences of lions and related species to construct phylogenetic trees and understand their evolutionary relationships. |

Ernst Mayr, a prominent evolutionary biologist, advanced taxonomy by emphasizing the biological species concept, defining species as groups capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring while being reproductively isolated. He regarded reproductive isolation as key to distinguishing species and viewed them as fundamental classification units. Mayr also promoted phylogenetic analysis, advocating for classifying organisms based on shared evolutionary ancestry through the principle of common descent.

Systematics provides a foundation for understanding organisms’ evolutionary relationships, adaptations, and ecological interactions. It integrates knowledge from various fields, including evolution, ecology, genetics, behavior, and comparative physiology, to build a comprehensive understanding of the diversity and complexity of life on Earth.

Let’s dive into how this organizational system emerged! Understanding the historical roots of taxonomy rank reveals why classifying life is far more complex than it may first appear.

Historical Background

Early attempts at formal classification can be traced back to ancient societies (ancient civilizations) like China and Egypt. In China, the ancient text “Shennong Ben Cao Jing” (The Classic of the Divine Farmer) documented various medicinal plants, classifying them based on their properties and therapeutic applications. This early classification system laid the groundwork for the development of Chinese herbal medicine. Similarly, the Ebers Papyrus of ancient Egypt described numerous medicinal plants and their healing properties, representing an early effort to organize botanical knowledge.

The context of medicinal plants significantly influenced the classification efforts of these forebears (ancient civilizations). Medicinal herbs (medicinal plants) held immense value in ancient societies as they served as their primary source of healing. Through direct observations (empirical observations) and documentation of different plants’ characteristics and applications, these societies developed rudimentary classification systems based on the medicinal properties of the plants.

However, their ability to accurately classify organisms was impeded (hindered) by several factors, including limited access to comprehensive information and the absence of advanced scientific methodologies. They primarily relied on observational data (empirical observations) and sometimes resorted to subjective judgments (subjective criteria) for classification, such as an organism’s perceived usefulness or harmfulness. Additionally, the lack of standardized languages and communication systems posed a challenge in sharing and disseminating knowledge (disseminating knowledge) across different regions and civilizations.

Understanding the historical background of taxonomy, including the early classification attempts by ancient societies, provides valuable context for appreciating the subsequent developments in the field, such as the contributions of the Greeks, the establishment of the Linnaean system, the evolution of classification methods post-Linnaeus, and the profound impact of Darwinian evolution.

From the Greeks to the Renaissance

The taxonomy field experienced seminal advancements (significant developments) from the Greeks to the Renaissance. A Greek philosopher, Aristotle, made groundbreaking contributions (pioneering contributions) to Western scientific classification by emphasizing the logical organization of living things. His Aristotelian system classified animals into groups based on shared characteristics like habitat (environment), body structure, and behavior (way of life).

Despite its limitations due to the absence of an evolutionary perspective, Aristotle’s emphasis on logical organization and categorization (classification) based on shared characteristics provided a framework (system) that resonated with scholars for centuries. His work was a cornerstone (foundation) of biological thought, influencing how people studied the natural world. His hierarchical classification system, emphasizing careful observation and categorization, remained widely accepted until the emergence of evolutionary theory in the 19th century.

Although lacking an evolutionary lens, Aristotle’s contributions paved the way (laid the groundwork) for future advancements (progress) in taxonomy and set the stage for developing more sophisticated classification systems.

The Renaissance marked a significant era of advancements (progress) in biology. During this time, groundbreaking figures like Andreas Vesalius revolutionized our understanding of the human body through his anatomical contributions. His influential book, “De humani corporis fabrica,” challenged existing anatomical beliefs and laid the foundation for modern anatomical study. Additionally, the Renaissance saw the establishment of botanical gardens, which became crucial centers for studying and cultivating plants.

These gardens provided researchers and naturalists invaluable opportunities to observe, classify, and document various plant species. This contributed to the development of botanical knowledge and significantly propelled advancements in the taxonomy field. The Renaissance period, therefore, witnessed remarkable progress in biological understanding, driven by the efforts of prominent figures like Vesalius and the establishment of botanical gardens, which facilitated the accumulation of knowledge and collaboration among naturalists, ultimately contributing to the advancement of taxonomy.

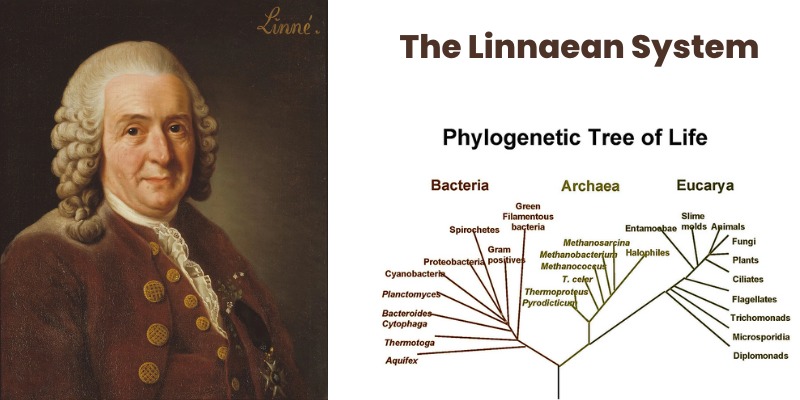

The Linnaean System

Carl Linnaeus revolutionized taxonomy by introducing binomial nomenclature and standardized hierarchical ranks in the 18th century. His two-part naming system assigned each species a unique Latin name comprising its genus and species epithet, ensuring precise communication and effective organization of biological data worldwide.

Linnaeus also developed a hierarchical classification system, grouping organisms into broader categories such as kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. This systematic framework provided a foundation for categorizing the diversity of life and comparing organisms across species, forming the basis for further scientific exploration.

Although Linnaeus aimed to create a natural classification system reflecting true relationships, his methods were influenced by Aristotelian logic, emphasizing perceived similarities and differences. By relying on anatomical features and reproductive organs for classification, his approach sometimes involved subjective judgments. Despite this, Linnaeus’s contributions laid the groundwork for evolutionary taxonomy, advancing our understanding of species relationships and evolutionary history.

Classification Post-Linnaeus

Biological classification has significantly evolved since Carl Linnaeus, incorporating new discoveries and moving closer to a truly natural system.

Taxonomy (classification) has undergone substantial evolution (significant development) since the time of Linnaeus. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and other scientists significantly contributed (played a crucial role) to refining (improving) classification by recognizing the importance of evolutionary relationships (lineages) among organisms. As an early advocate (proponent) of evolution, Lamarck proposed the idea of inherited acquired characteristics, suggesting that organisms could adapt (change) their traits in response to their environment and pass on these adaptations (transmit these acquired traits) to their offspring, leading to evolutionary change.

While Lamarck’s specific theories on inheritance were later disproven, his recognition of the dynamic nature of species (acknowledging that species change over time) and their interconnectedness (relationships) influenced (shaped) the development of classification systems. He emphasized (highlighted) the need to consider the evolutionary history (past development) of organisms when organizing them into taxonomic groups.

Wilhelm Hofmeister, a botanist, contributed significantly to understanding plant reproduction through his studies on alternation of generations. He observed that plants have two distinct stages in their life cycles: a sporophyte (spore-producing generation) and a gametophyte (gamete-producing generation). This discovery highlighted the importance (emphasized the need) of considering both sexual and asexual stages in the classification of plants. Hofmeister’s work provided valuable insights (understanding) into the complex life cycles of plants and contributed to the refinement (helped improve) of plant classification systems.

Ernst Haeckel, a prominent biologist, proposed the term “Protista” to describe a group of organisms that did not fit neatly into the existing plant or animal kingdoms. He recognized that diverse (varied) microscopic organisms, such as algae and protozoa, defied traditional classification schemes. By introducing the term “Protista,” he created a new kingdom encompassing these organisms. This expansion (broadening) of classification allowed for a more accurate representation (faithful depiction) of the diversity of life, particularly among unicellular and microscopic organisms.

Hofmeister’s work on alternating generations and Haeckel’s proposal of the term “Protista” contributed to the ongoing expansion and refinement of classification systems. They recognized the need to accommodate organisms (include) that did not fit into traditional categories and provided a framework (structure) for incorporating a broader range of organisms into taxonomic schemes. These advancements (developments) paved the way for a more comprehensive understanding (thorough knowledge) of the diverse life forms on Earth and set the stage for further developments (progress) in taxonomy.

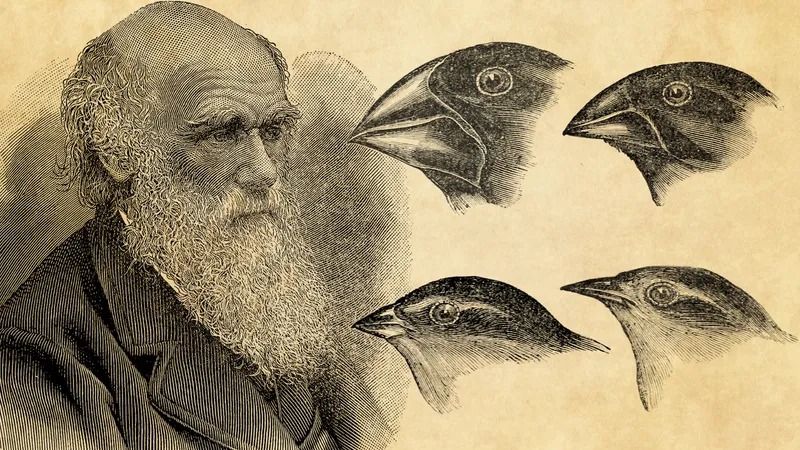

Impact of Darwinian Evolution

Darwinian evolution (theory of evolution by natural selection) profoundly impacted (significantly influenced) the field of biological classification, leading to substantial changes (dramatic shifts) in how organisms are classified and categorized. Darwin’s theory highlighted the significance of shared evolutionary history (common ancestry) and common descent among organisms. This led to a paradigm shift (major change) in taxonomy, moving towards a phylogenetic approach (evolutionary classification) where classification is based on the evolutionary relationships (lineages) and branching patterns among species. Rather than solely relying on unchanging features (static characteristics) like anatomical structures, taxonomists began incorporating information from various fields, including genetics, molecular biology, and others, to determine organisms’ actual evolutionary relatedness (establish true evolutionary connections).

Darwinian evolution prompted the reevaluation and revision (reassessment and reconsideration) of specific classifications. Several organisms were reclassified (repositioned) based on their evolutionary relationships (lineages) rather than superficial similarities. For example, certain bird species were reclassified (regrouped) based on their genetic relationships, leading to changes in their placement within the taxonomic hierarchy. These revisions sometimes sparked debates (discussions) among taxonomists as different perspectives and interpretations of evolutionary relationships emerged.

Darwinian evolution (theory of evolution by natural selection) also presented challenges (difficulties) at the species level due to geographical variation and reticulate evolution. Geographical variation refers to the phenomenon where populations of the same species can exhibit variations in their traits (differences in characteristics) across different geographic regions. This variation can lead to difficulties (challenges) in how species are defined and classified. Reticulate evolution, which involves the exchange of genetic material between different species (horizontal gene transfer), further complicates classification at the species level. These ongoing challenges have prompted continuous discussions (active research) and debates (conversations) among taxonomists regarding the appropriate classification of certain species and their boundaries.

Overall, Darwinian evolution reshaped biological classification by emphasizing the importance of evolutionary relationships and phylogenetic patterns. It led to the revision of classifications (reorganization) based on evolutionary principles and triggered ongoing debates and reevaluation (continuous research and discussions) of specific taxonomic groups. The challenges posed by geographical variation and reticulate evolution continue to be active areas of research and discussion within the taxonomy field.

8 major ranks in taxonomy

In his landmark publications, such as the Systema Naturae, Carl Linnaeus used a ranking scale limited to kingdom, class, order, genus, species, and one rank below species. Today, the nomenclature is regulated by the nomenclature codes. There are seven main taxonomic ranks: kingdom, phylum or division, class, order, family, genus, and species, In addition, domain (proposed by Card Woese) is now widely used as a fundamental rank, although it is not mentioned in any of the nomenclature codes, and is a synonym for dominion (Latin: dominium), introduced by Moore in 1974.

Now that we’ve covered the concept of taxonomy, let’s explore the hierarchical structure of classification by going into the 8 significant ranks of taxonomy rank.

Main taxonomy ranks

| Latin | English |

| regio | domain |

| regnum | kingdom |

| phylum | phylum (in zoology)/ division (in botany) |

| classis | class |

| ordo | order |

| familia | family |

| genus | genus |

| species | species |

Domain

Definition and Origin

In taxonomy rank; a domain is a broad category representing the highest level of classification for organisms. It is used to group organisms based on fundamental characteristics and evolutionary relationships. The term “domain” was not introduced until 1990, over 250 years after Linnaeus developed his classification system in 1735. Carl Woese introduced the concept of domains in the 1970s to classify organisms into three distinct groups: Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya. This hierarchical system provides a framework for understanding the diversity of life on Earth and how organisms are related to one another.

Characteristics of domains

The three domains of life, Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya, are characterized by distinct features and evolutionary relationships:

- Bacteria: Bacteria are single-celled organisms that lack a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles. They are found in various environments, including soil, water, and the human body. Bacteria play crucial roles in various ecological processes and can benefit and harm humans.

- Archaea: Archaea are also single-celled organisms with distinct biochemical and genetic characteristics that set them apart from bacteria. They are often found in extreme environments such as hot springs, deep-sea hydrothermal vents, and highly acidic or saline habitats. Archaea are known for their ability to thrive in harsh conditions and have unique metabolic pathways.

- Eukarya: Eukarya includes all living organisms that are not bacteria or archaea. This domain encompasses a vast diversity of organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and protists. Eukaryotes are characterized by having cells with a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles. They exhibit complex cellular organization and often have multicellular forms, allowing for various biological functions and ecological roles.

The importance of domain

Domains play a crucial role in the taxonomy field and provide a fundamental classification framework for understanding the diversity of life on Earth. Domains help organize and classify organisms into broad, distinct categories based on their fundamental characteristics and evolutionary relationships. Taxonomists can establish a hierarchical structure that reflects the relatedness and diversity of life forms by grouping organisms into domains. This classification system aids scientists in studying and understanding the evolutionary history and relationships between different organisms.

Domains allow for comparative analysis across different organisms. Taxonomists can make generalizations and comparisons within and across these broad categories by categorizing organisms into domains. This approach facilitates the identification of shared traits and evolutionary patterns and studies common ancestry among organisms within a particular domain.

Kingdom

Pre-Domain Classification

Before the introduction of domains, the highest taxonomic rank (classification level) in traditional systems was indeed the kingdom. Kingdoms were historically considered the broadest classification level, encompassing (including) a wide range of organisms with shared characteristics and evolutionary relationships (lineages). The traditionally recognized kingdoms, before the introduction of domains, included Animalia (animals), Plantae (plants), Fungi (fungi), Protista (protists), Archaea (archaea), and Bacteria (bacteria). Each kingdom represented a distinct group of organisms with unique characteristics and biological features.

Evolution and Revision

The classification of kingdoms has undergone revisions (reevaluations) over time as our understanding of organisms and their relationships has advanced (improved). The classification of organisms as Protista is not always accurate due to the diverse nature of eukaryotic organisms it includes. Protista was initially considered a catch-all (general category) kingdom for eukaryotes that did not fit neatly into other established kingdoms. However, Protista’s vast array of organisms, including protozoa, algae, and slime molds, exhibited significant differences (variations) in evolutionary history, genetics, and ecological roles. This diversity (complexity) presented challenges in categorizing and defining (classifying) Protista as a coherent (unified) taxonomic group.

Various splits and revisions (proposed changes) have been proposed to address the challenges posed by Protista and improve the accuracy of kingdom-level classification. For instance, classifying Protozoa as a separate kingdom has been suggested to emphasize these diverse single-celled eukaryotic organisms’ distinct characteristics and evolutionary relationships (lineages). Similarly, the proposed kingdom Chromista aims to separate certain groups of algae with unique genetic and evolutionary features.

Phylum

Phylum is a taxonomic rank that falls between (exists in the hierarchy between) the broader category of kingdom and the more specific category of class. It provides a more specific classification (narrower grouping) than kingdom but is less specific (broader grouping) than class. As an intermediate classification level, a phylum helps group organisms with shared characteristics and evolutionary relationships (common lineages).

The animal kingdom (Animalia) has approximately 31 recognized phyla (groups). Each phylum represents a distinct and diverse group of organisms with unique anatomical, physiological, and developmental characteristics. Chordata is an example of a phylum within Animalia. It includes organisms with a notochord (flexible rod-like structure), a dorsal nerve cord, and a post-anal tail at some life cycle stage. Chordates encompass many animals, including vertebrates (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish) and some invertebrates.

Additionally, the introduction of domains created a higher taxonomic rank above kingdoms. The three domains are Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. Kingdoms are now classified within these broader domains, reflecting a more comprehensive understanding of life’s diversity and evolutionary relationships on Earth.

Class

Class, introduced by Carl Linnaeus, the founding father of modern taxonomy, is a fundamental taxonomic level (classification level) in the hierarchical classification system. During his time (18th century), class was the broadest level (highest rank) for categorizing organisms based on shared characteristics (common features). It existed above the ranks of order and genus and below the newer rank (later introduced rank) of phylum.

Within the animal kingdom, where a vast diversity of organisms (variety of living things) exists, class serves as a taxonomic level (functions as a classification category) that groups related organisms. There are approximately 6 recognized classes in Animalia. Some notable examples include Mammalia (mammals), Aves (birds), and Reptilia (reptiles). Each class represents a distinct group of organisms with shared characteristics (common features) like anatomical features, reproductive strategies, and ecological adaptations.

Order

Order, a more specific level (narrower rank) than class, represents a grouping of organisms with shared characteristics and evolutionary relationships (common features and lineages). In the hierarchical structure, order falls below class and above family. It provides a more specific grouping (precise classification) within a class based on similarities in morphology, behavior, and other relevant characteristics. The number of orders within a class can vary (may differ) depending on the classification methods used, the diversity of organisms (variety of living things) within the class, and ongoing scientific research and discoveries.

Examples of orders within different classes include Squamata (lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians) in the class Reptilia (reptiles). These orders represent distinct groups of organisms with shared characteristics and evolutionary relationships.

Within the order Squamata, there are further divisions into suborders, such as Serpentes (snakes) and Lacertilia (lizards). Examples of families within these suborders include Viperidae (vipers), Colubridae (non-venomous snakes), Gekkonidae (geckos), and Iguanidae (iguanas). Each group showcases unique adaptations and lineage while sharing common traits that classify them under the order Squamata.

Family

Family, a more specific level (narrower rank) than order, groups organisms with even closer similarities and evolutionary relationships (greater resemblance and shared lineage). Within the hierarchical system, family falls below order and above genus. It provides a more specific grouping (precise classification) within an order based on shared characteristics like anatomical features, behavior, and genetic relationships.

Families represent distinct groups of organisms within a class. For instance, within the class Reptilia, there are various families grouped under different orders, such as Crocodilia and Squamata. Each family includes related species that share common characteristics and evolutionary history.

The number of families within a class or order varies based on the diversity and complexity of the organisms. For example, the order Squamata (lizards and snakes) includes 67 recognized families, such as Gekkonidae (geckos), Viperidae (vipers), Colubridae (non-venomous snakes), and Iguanidae (iguanas). The order Crocodilia consists of three recognized families: Crocodylidae (crocodiles), Alligatoridae (alligators and caimans), and Gavialidae (gharials), each representing unique evolutionary lineages and traits.

Genus

Genus, a critical taxonomic rank (classification level) in the binomial nomenclature system (two-part naming system) developed by Carl Linnaeus, plays a crucial role in naming and classifying organisms. This system assigns each species (unique group of organisms) a unique two-part scientific name. The first part represents the genus (group of closely related species) to which the species belongs, and the second part represents the species itself. For example, in the scientific name Homo sapiens, “Homo” is the genus and “sapiens” is the species.

Genus names are always capitalized in scientific names, while species names (names of specific groups of organisms) are never capitalized. This convention helps to distinguish between the two parts of the scientific name. Additionally, scientific names are italicized (or underlined if italics are not available) in written text to indicate that they are in Latinized form.

Within the hierarchical classification system, genus falls between family (higher rank) and species (lower rank). It represents a group of closely related species (organisms with a recent common ancestor) with common characteristics and evolutionary ancestry (shared features and lineage). For example, within the family Felidae (felines), the genus Panthera includes species such as Panthera leo (lion), Panthera tigris (tiger), and Panthera pardus (leopard). These species share a more recent common ancestor within the genus Panthera compared to other members of the Felidae family.

Species

Species, the most specific major taxonomic rank (most precise and fundamental classification level) in the hierarchy, represents a group of organisms capable of interbreeding (mating) and producing fertile offspring (viable progeny) . It is the smallest and most specific rank in the classification system, providing the most precise classification level for organisms.

The binomial nomenclature system developed by Carl Linnaeus assigns each species a unique two-part scientific name. The first part represents the genus, and the second represents the species. Scientific names, including species names, are italicized (or underlined if italics are unavailable) to indicate their Latinized form. Importantly, as mentioned earlier, species names are never capitalized. For example, Ursus americanus represents the scientific name of the American black bear, where “Ursus” is the genus and “americanus” is the species.

In some cases, species can be further divided into subspecies. Subspecies are even more specific categories within a species with distinct characteristics typically found in specific geographic regions. They are represented by a third part added to the scientific name, following the species name. For example, Ursus americanus floridanus represents the subspecies of the American black bear found in Florida.

Practical Applications of Taxonomic Ranks

Practical applications of taxonomic ranks are diverse and have implications in various fields. Some examples illustrate the significance of taxonomic ranks in conservation, medicine and research, agriculture, and bioprospecting:

Conservation:

Taxonomic ranks play a crucial role in conservation efforts by providing a framework to identify and protect endangered species. For instance:

- The IUCN Red List, which assesses the conservation status of species, relies on taxonomic information to determine the endangered status of a species. By identifying species at the genus or species level, conservationists can focus efforts on preserving specific groups or populations that are at risk.

- Keystone species, which significantly impact the structure and function of ecosystems, can be identified based on their taxonomic relationship to endangered or vulnerable groups. For example, the African elephant (Loxodonta africana) is a keystone species due to its vital role in shaping savannah ecosystems.

Medicine & Research:

Proper taxonomy rank is essential in various aspects of medicine and research, including the discovery and development of medications. Some examples are:

- Animal-derived cancer medications, such as paclitaxel (trade name Taxol), were initially discovered from the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia). The correct taxonomic identification of the tree facilitated the identification of the compound with anti-cancer properties.

- Taxonomic classification of bacteria is crucial in understanding and combating infectious diseases. For instance, identifying and classifying different strains of the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis has helped develop targeted treatments for tuberculosis.

Agriculture:

Understanding the taxonomic relationships between pests and their relatives can aid in developing effective and environmentally friendly control methods. Examples include:

- Biological control methods, such as natural predators or parasites, often rely on identifying the taxonomic relationships between pests and their natural enemies. For instance, the use of parasitic wasps (family Braconidae) to control agricultural pests like aphids and caterpillars is based on understanding the taxonomic relationships within the order Hymenoptera.

- Crop breeding programs can benefit from taxonomic information to identify and incorporate genetic traits from related species. For example, wild relatives of cultivated crops within the same family (e.g., Solanaceae) may possess resistance genes that can be used to develop pest-resistant crop varieties.

Bioprospecting:

Taxonomy rank is crucial in bioprospecting, the search for valuable resources and compounds from organisms. Recent intriguing breakthroughs include:

- The discovery of a painkiller derived from spider venom. Scientists identified specific compounds within the venom of certain spider species by understanding their taxonomic relationships. This discovery can potentially lead to the development of novel pain medications.

- Exploration of marine environments has revealed a wealth of biodiversity with unique biochemical properties. Taxonomic classification helps identify promising organisms for bioprospecting, such as bacteria that produce antibiotic compounds or marine organisms with potential pharmaceutical applications.

Controversies and ongoing developments

Controversies and developments in taxonomy continue to shape our understanding of the natural world. Here are some key points regarding controversies, ongoing debates, and the role of formal structures in taxonomy rank:

Lumpers vs. Splitters:

The terms “lumpers” and “splitters” describe different approaches to taxonomy rank. Lumpers prefer to group organisms into larger, more inclusive taxonomic categories, emphasizing similarities and minimizing divisions. Conversely, splitters prefer recognizing smaller, more distinct taxonomic units, emphasizing differences and promoting finer-scale classifications.

A case study involving charismatic mammals that has sparked debate is splitting the African elephant into two species: the African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) and the African savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana). This split is based on genetic, morphological, and behavioral differences between the two populations. The debate revolves around whether these differences warrant separate species status or if they should be considered subspecies or populations of a single species.

Research and Ongoing Debates:

Trends in Ecology & Evolution (TREE) and similar journals often feature hot debates and ongoing discussions in taxonomy. These debates typically address emerging research and challenges in classifying and understanding biodiversity. Some accessible summaries in such journals may include discussions like:

- The reclassification of certain groups based on molecular data, challenging traditional morphological classifications.

- The debate surrounding the species concept and the need to incorporate ecological and genetic factors for more accurate species delineation.

- Ongoing discussions about the appropriate use of different data types (morphological, genetic, ecological) and methods in taxonomic research.

International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN):

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) establishes the formal rules and conventions not just for classification logic but also for naming animals and ensuring stability and uniformity in taxonomic nomenclature. It provides comprehensive guidelines for forming, using, and conserving scientific names. Additionally, the ICZN sets standards for the publication of new names, enforces rules of priority, and outlines procedures for resolving nomenclatural disputes.

FAQs

Why does every living thing have a scientific name that looks gibberish?

Scientific names, or binomial nomenclature, classify and identify organisms in a standardized way using Latin or Greek. They offer several advantages:

- Universal Identification: Provide a common, stable language for scientists worldwide.

- Clarity and Precision: Reflect characteristics, habitats, or evolutionary relationships (e.g., Panthera leo for the African lion).

- Avoiding Confusion: Eliminate ambiguity caused by regional common names.

- Evolutionary Insights: Highlight shared evolutionary histories through a hierarchical classification system.

Can a single animal belong to multiple kingdoms at once?

No, a single animal cannot belong to multiple kingdoms. In biological classification, organisms are grouped into taxonomic ranks based on their characteristics and evolutionary relationships, with the kingdom being the highest rank. Each organism is assigned to one of five recognized kingdoms—Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Protista, or Monera—based on its fundamental traits.

Each kingdom represents a distinct group with unique characteristics and evolutionary history. For instance, animals are multicellular, heterotrophic organisms with specialized tissues, while plants are multicellular, photosynthetic, and have cell walls. Since no organism can simultaneously exhibit the defining traits of multiple kingdoms, a single animal cannot belong to more than one kingdom.

How is sorting all of life into categories even helpful?

Sorting all of life into categories through biological classification is helpful for 5 reasons:

- Organization: Classification organizes Earth’s diverse life forms into hierarchical groups based on shared traits, simplifying complexity.

- Identification and Naming: Provides standardized names and categories for clear communication in research, education, and conservation.

- Evolutionary Relationships: Highlights evolutionary history and relatedness, aiding in understanding life’s origins and evolution.

- Predictive Power: Helps infer organisms’ traits, behaviors, and ecological roles, benefiting medicine, agriculture, and ecology.

- Conservation and Biodiversity: Supports conservation by assessing species’ distribution, threats, and biodiversity changes for effective action.

Have scientists always agreed on how to organize animals?

No, scientists have not always agreed on how to classify animals. The classification of organisms has evolved over time as new evidence and discoveries have improved our understanding of biology and species relationships. Early systems, like those of Aristotle, provided basic categorizations, but it was Carl Linnaeus in the 18th century who formalized the modern system of binomial nomenclature and hierarchical classification, organizing organisms into categories like kingdom, phylum, and species.

Advances in fields like comparative anatomy, genetics, and molecular biology have since deepened our understanding of evolutionary relationships. New techniques, such as DNA sequencing, have led to debates and revisions, resulting in the reclassification and reorganization of many animal groups as scientists uncover more about their genetic and evolutionary connections.

Which comes first, discovering a new species or deciding where it fits in the family tree?

The discovery of a new species and its placement in the family tree can occur in either order, depending on the context. Typically, species are identified through fieldwork or genetic analysis, followed by studying traits and genetics to determine their evolutionary relationships.

In some cases, gaps in the family tree guide researchers to anticipate and locate new species, allowing preliminary placement based on similarities to known species. Ultimately, both steps are interconnected, with discovery leading to classification or existing knowledge aiding in identifying and positioning the species.

Taxonomy provides a vital framework for understanding life’s diversity, organizing organisms by shared traits and evolutionary relationships. From Linnaeus’s binomial nomenclature to modern phylogenetics, it has evolved to reflect scientific discoveries, aiding fields like conservation, medicine, and agriculture.

Beyond classification, taxonomy fosters biodiversity preservation and inspires discovery. Despite ongoing debates and refinements, its systematic approach remains essential for exploring evolutionary connections and protecting life’s intricate web. By bridging science and practicality, taxonomy continues to deepen our appreciation for the natural world and its interconnected wonders.