What are Vertebrates?

Vertebrates are creatures with a backbone that safeguards their spinal cord, distinguishing them from invertebrates. These animals possess specific characteristics that make them unique and intriguing for study.

This group includes mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, all characterized by the presence of a vertebral column that supports their body structure and protects the spinal cord.

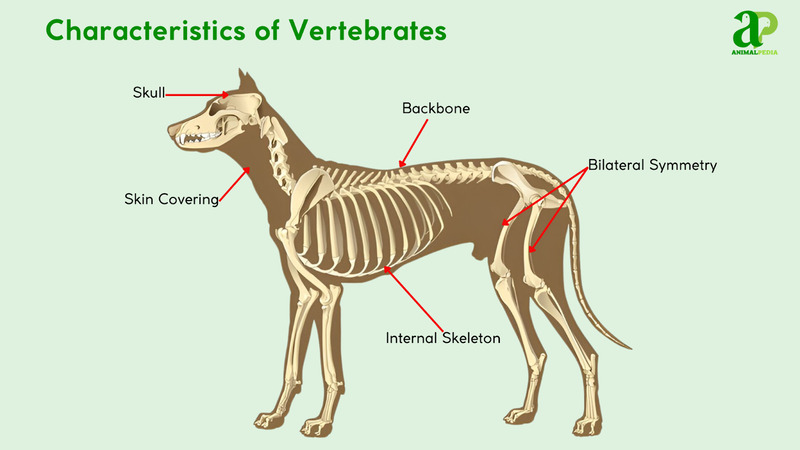

What are the characteristics of Vertebrates?

Vertebrates share a set of defining physical characteristics that distinguish them from other animals. Here’s an overview of their key traits:

- Vertebral Column (Backbone): All vertebrates have a spinal column made of bone or cartilage, providing structural support and flexibility. This backbone consists of individual vertebrae that vary in size and shape depending on the species.

- Internal Skeleton: They possess an endoskeleton, typically made of bone, though some, like sharks, have cartilage instead. This framework supports the body and anchors muscles.

- Skull: Vertebrates have a well-developed skull that encases and protects the brain, a feature tied to their complex nervous systems.

- Bilateral Symmetry: Their bodies are symmetrical along a central axis, meaning the left and right sides are mirror images, aiding in balanced movement and coordination.

- Skin Covering: Their skin varies widely—mammals have hair or fur, birds have feathers, reptiles have scales, amphibians have moist skin, and fish have scales or slimy coatings—each suited to their lifestyle.

These characteristics collectively enable vertebrates to occupy diverse ecological niches, from deep oceans to high skies, showcasing their adaptability and evolutionary success.

How are Vertebrates Different from Invertebrates?

Vertebrates and invertebrates diverge fundamentally in their anatomical architecture, a distinction rooted in the presence or absence of a vertebral column. Vertebrates encase the spinal cord and support an internal skeleton of bone or cartilage. In contrast, the invertebrates lack this structure, relying instead on diverse support mechanisms like exoskeletons (e.g., chitin in arthropods) or hydrostatic pressure (e.g., in worms).

This backbone in vertebrates facilitates a robust framework for muscle attachment and movement, while invertebrates often exhibit greater flexibility or rigidity depending on their adaptations. Additionally, vertebrates typically boast a centralized nervous system with a brain and spinal cord, contrasting with the often decentralized or rudimentary nervous systems of invertebrates, such as the nerve nets in cnidarians.

The table below encapsulates these distinctions across key traits between vertebrates and invertebrates.

|

Aspect |

Vertebrates |

Invertebrates |

| Presence of Backbone | Yes | No |

| Examples | Mammals, Birds, Fish | Insects, Jellyfish, Worms |

| Body Symmetry | Bilateral | Bilateral, Radial, or None |

| Nervous System | Centralized (Brain + Spinal Cord) | Decentralized or Simple |

| Reproduction | Mostly Internal | Internal or External |

| Size Range | Small to Large (e.g., Whale) | Microscopic to Large (e.g., Squid) |

| Habitat | Land, Water, Air | All Ecosystems |

| Respiratory System | Lungs or Gills | Gills, Tracheae, or Diffusion |

| Circulatory System | Closed | Open or None |

| Exoskeleton | No | Yes (e.g., Arthropods) or None |

How are Vertebrates classified?

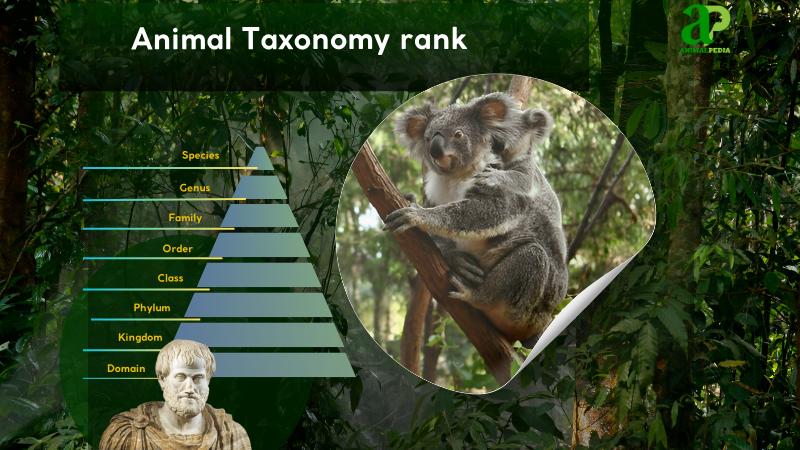

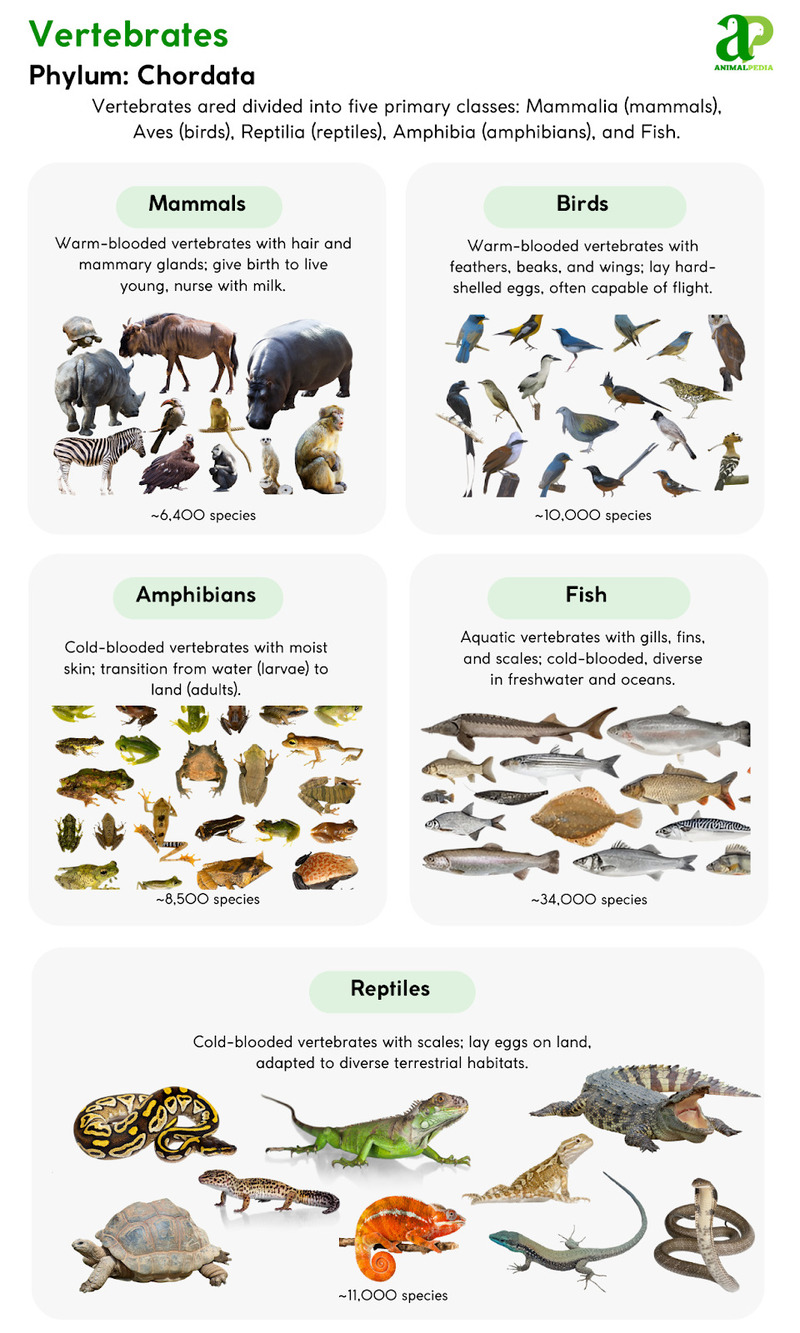

Vertebrates are classified within the phylum Chordata, a system rooted in Linnaean taxonomy, developed by Carl Linnaeus in the 18th century, and refined through cladistics based on shared evolutionary traits like the presence of a notochord, dorsal nerve cord, and vertebral column.

Classification hinges on anatomical, physiological, and genetic distinctions, organizing vertebrates into five primary classes: Mammalia (mammals), Aves (birds), Reptilia (reptiles), Amphibia (amphibians), and Pisces (fish, often split into Chondrichthyes for cartilaginous fish and Osteichthyes for bony fish).

- Class Mammalia (Mammals):

Mammals are warm-blooded vertebrates with hair or fur, mammary glands, and a four-chambered heart, comprising about 6,400 species across 26 orders. They thrive in diverse habitats, from deserts to oceans. The largest order, Rodentia, dominates with over 2,277 species, while Primates include humans, showcasing advanced cognition.

- Order Rodentia (Examples: Mice, rats, squirrels): Largest mammal order, known for ever-growing incisors requiring constant gnawing.

- Order Chiroptera (Examples: Bats): Only mammals with true flight, featuring wings of elongated fingers and skin membranes.

- Order Carnivora (Examples: Dogs, cats, bears): Predators with sharp, meat-tearing teeth and varied hunting behaviors.

- Order Primates (Examples: Humans, monkeys, apes): Noted for flexible limbs, stereoscopic vision, and social complexity.

- Additional Orders: Cetacea (whales), Artiodactyla (deer), Monotremata (platypus).

- Class Aves (Birds):

Birds, warm-blooded with feathers and beaks, span about 10,000 species across 40 orders. Adapted for flight (most species), they inhabit all ecosystems. Passeriformes, the largest order, boasts over 5,700 species.

- Order Passeriformes (Examples: Sparrows, crows): Perching birds with diverse songs and adaptable feet.

- Order Falconiformes (Examples: Eagles, hawks): Raptors with keen vision and hooked beaks for predation.

- Order Anseriformes (Examples: Ducks, geese): Waterfowl with webbed feet and flattened bills.

- Order Strigiformes (Examples: Owls): Nocturnal hunters with silent flight and facial discs.

- Additional Orders: Psittaciformes (parrots), Galliformes (chickens).

- Class Reptilia (Reptiles):

Cold-blooded with scales, reptiles include about 11,000 species across 4 main orders. They excel in arid and tropical zones. Squamata is the largest, with nearly 10,000 species.

- Order Squamata (Examples: Lizards, snakes): Flexible jaws and scales; snakes lack limbs.

- Order Testudines (Examples: Turtles, tortoises): Bony shells protect these slow movers.

- Order Crocodilia (Examples: Crocodiles, alligators): Aquatic predators with powerful jaws.

- Order Rhynchocephalia (Example: Tuatara): Rare, lizard-like with a primitive skull.

- Additional Orders: None significant; minor extinct groups exist.

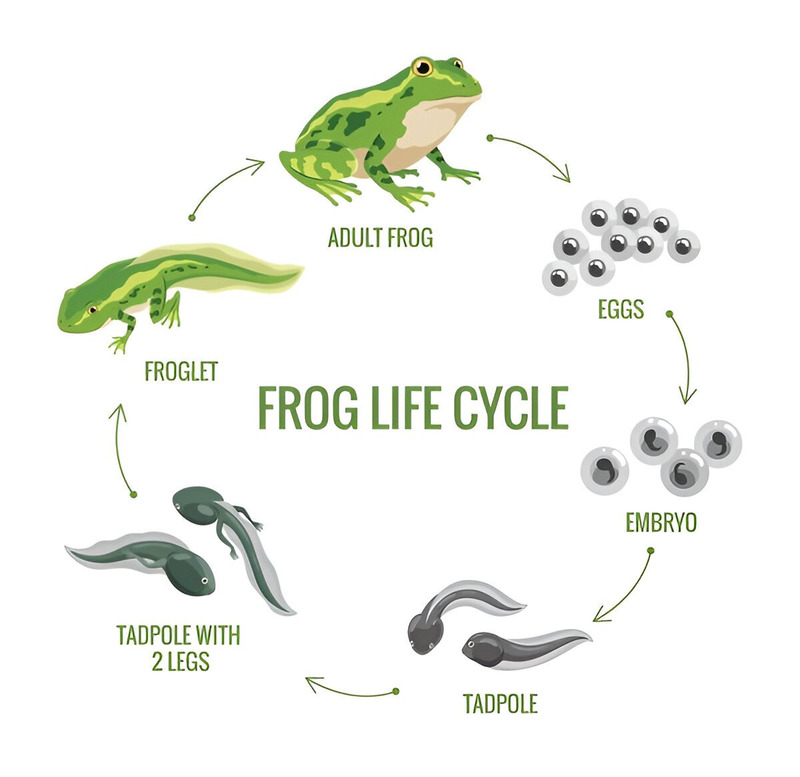

- Class Amphibia (Amphibians):

Amphibians are cold-blooded with moist skin. They number about 8,000 species across 3 orders and bridge aquatic and terrestrial life. Anura dominates with over 7,000 species.

- Order Anura (Examples: Frogs, toads): Jumping legs and vocal sacs define this group.

- Order Caudata (Examples: Salamanders): Elongated bodies with tails, often regenerating limbs.

- Order Gymnophiona (Examples: Caecilians): Legless, burrowing, and worm-like in form.

- Additional Orders: None; these cover all living amphibians.

- Class Fish:

Fish, encompassing jawed aquatic vertebrates, include over 34,000 species across numerous orders (exact count varies by system). They dominate water ecosystems. Perciformes is the largest, with over 10,000 species.

- Order Perciformes (Examples: Tuna, perch): Diverse bony fish with spiny fins.

- Order Siluriformes (Examples: Catfish): Whisker-like barbels aid in murky waters.

- Order Chondrichthyes (Examples: Sharks, rays): Cartilaginous skeletons and keen senses.

- Order Cypriniformes (Examples: Carp, minnows): Freshwater fish with toothless jaws.

- Additional Orders: Clupeiformes (herrings), Anguilliformes (eels).

The following phylogenetic tree depicts the hierarchical classification within Vertebrates , illustrating the relationships from subclasses to families.

Chordata (Phylum of Chordates)

├── Class Mammalia (Mammals: 6,400 species, 26 orders)

│ ├── Order Rodentia (Rodents: Mice, squirrels – >2,277 species)

│ ├── Order Chiroptera (Bats: Flight-capable, wings from fingers)

│ ├── Order Carnivora (Carnivores: Dogs, cats, bears)

│ ├── Order Primates (Primates: Humans, monkeys – stereoscopic vision)

│ └── Additional Orders (Cetacea: Whales; Artiodactyla: Deer; Monotremata: Platypus)

├── Class Aves (Birds: 10,000 species, 40 orders)

│ ├── Order Passeriformes (Perching birds: Sparrows – >5,700 species, adaptable feet)

│ ├── Order Falconiformes (Raptors: Eagles, hawks – hooked beaks)

│ ├── Order Anseriformes (Waterfowl: Ducks, geese – webbed feet)

│ ├── Order Strigiformes (Owls: Nocturnal, silent flight)

│ └── Additional Orders (Psittaciformes: Parrots; Galliformes: Chickens)

├── Class Reptilia (Reptiles: 11,000 species, 4 main orders)

│ ├── Order Squamata (Lizards, snakes: ~10,000 species, flexible jaws)

│ ├── Order Testudines (Turtles: Bony shells for protection)

│ ├── Order Crocodilia (Crocodiles: Aquatic hunters, strong jaws)

│ ├── Order Rhynchocephalia (Tuatara: Rare, primitive lizard-like)

│ └── Additional Orders (None significant)

├── Class Amphibia (Amphibians: 8,000 species, 3 orders)

│ ├── Order Anura (Frogs, toads: >7,000 species, jumping legs)

│ ├── Order Caudata (Salamanders: Elongated, limb-regenerating)

│ └── Order Gymnophiona (Caecilians: Legless, burrowing)

└── Class Pisces (Fish: >34,000 species, numerous orders)

├── Order Perciformes (Perch-like: Tuna – >10,000 species, spiny fins)

├── Order Siluriformes (Catfish: Sensory barbels)

├── Order Chondrichthyes (Cartilaginous: Sharks, rays)

├── Order Cypriniformes (Carps: Freshwater, toothless jaws)

└── Additional Orders (Clupeiformes: Herrings; Anguilliformes: Eels)

What did Vertebrate evolve from?

Vertebrates evolved from early chordates, a group of animals defined by the presence of a notochord—a flexible, rod-like structure that provides support and is a precursor to the backbone.

The evolution of vertebrates spans over 500 million years, documenting the transition from simple marine organisms to the diverse array of vertebrate species that inhabit nearly every ecosystem on our planet today.

In particular, the evolution of vertebrates followed a progressive path, with each major transition building upon previous adaptations:

- Cambrian Period (~540 Mya) – Chordate Origins

Early chordates like Pikaia appeared with notochords, dorsal nerve cords, pharyngeal slits, and post-anal tails. These small swimming organisms established the foundational body plan for all future vertebrates while lacking true vertebrae.

- Ordovician Period (~485 Mya) – First Vertebrates

Jawless fish (Agnatha) emerged as the first true vertebrates. Ostracoderms and similar creatures developed rudimentary vertebrae surrounding their notochords, typically protected by bony armor plates and relying on filter-feeding for sustenance.

- Silurian Period (~420 Mya) – Jawed Fish Emerge

Jaws evolved from modified gill arches in early gnathostomes like placoderms. This adaptation dramatically enhanced feeding efficiency, enabled active predation, and expanded potential food sources, triggering new evolutionary pathways in ancient oceans.

- Devonian Period (~375 Mya) – Lobed-Fin Fish & Tetrapod Transition

Lobe-finned fish like Tiktaalik developed limb-like fins with bones homologous to tetrapod limbs. These transitional forms could support their weight in shallow water and possibly venture briefly onto land, bridging aquatic and terrestrial existence.

- Carboniferous Period (~340 Mya) – Amphibians Dominate

Early amphibians like Ichthyostega adapted to land with functional lungs and robust limbs. These pioneers diversified across swampy environments while remaining tied to water for reproduction, as their eggs and larvae required aquatic development.

- Permian Period (~280 Mya) – Reptilian Rise

The amniotic egg evolved, containing specialized membranes protecting embryos in self-contained environments. This freed vertebrates from water-dependent reproduction and gave rise to reptiles, allowing exploitation of drier habitats previously inaccessible to amphibians.

- Triassic Period (~230 Mya) – Dinosaurs & Mammal Ancestors

Following the Permian extinction, surviving vertebrates diversified into new evolutionary lines. Archosaurs (future dinosaurs and birds) flourished alongside synapsids (mammal ancestors). Early dinosaurs like Eoraptor appeared as distinct evolutionary trajectories emerged.

- Jurassic Period (~165 Mya) – Birds Take Flight

Feathered dinosaurs evolved into the first birds, with Archaeopteryx representing a transitional form. Feathers, initially serving as insulation or display, enabled powered flight in some lineages, opening previously unavailable aerial niches to vertebrates.

- Cretaceous Period (~120 Mya) – Mammalian Diversification

Early mammals diversified while dinosaurs dominated. The split between placental and marsupial mammals established different reproductive strategies. These small, nocturnal creatures occupied specialized niches, developing enhanced senses and more efficient teeth.

- Cenozoic Era (~66 Mya – Present) – Modern Vertebrates

After non-avian dinosaur extinction, mammals and birds underwent explosive adaptive radiation. This “Age of Mammals” saw familiar groups emerge—carnivores, ungulates, cetaceans, and primates—eventually leading to humans, whose cultural adaptations transformed the planet.

What are the behaviours of Vertebrates?

Let’s explore the fascinating behaviors of vertebrates!

One interesting aspect is their varied ways of moving, which range from swimming in water to walking on land.

Understanding the different locomotion styles of vertebrates can provide valuable insights into their survival strategies and adaptations.

Locomotion

When we observe how vertebrates move and navigate their surroundings, we’re amazed by the variety of ways they do so. Birds elegantly take flight, using their wings to glide through the air with precision.

Mammals, on the other hand, rely on their strong legs to run, jump, climb, and sometimes even swim. Fish smoothly propel themselves underwater with fins and streamlined bodies, effortlessly navigating their aquatic homes.

Reptiles exhibit a range of movement styles, from crawling to swimming and burrowing. Amphibians show off their versatility by easily switching between hopping, crawling, and swimming. The diverse locomotion of vertebrates highlights their adaptability and variety in the animal kingdom.

Crawling

Crawling is a common method of movement seen in various animals, including reptiles, amphibians, and some mammals during specific stages of their development. This locomotion allows creatures like lizards and snakes to move without relying on walking or running. It’s also a way for human babies to explore their surroundings and build strength in their limbs before they start walking.

By crawling, these animals can travel efficiently across different types of terrain such as forests, beaches, or rocky areas. It gives them the freedom to navigate through their environments with ease.

Swimming

Swimming is a crucial skill for many animals living in water, allowing them to move effortlessly and explore their aquatic homes. It’s not just a way to get around; it’s a vital tool for survival, offering the freedom to glide through the water with ease. Whether it’s the graceful dolphin slicing through the waves or the playful otter frolicking in rivers, swimming opens up a whole new world beneath the surface.

It’s all about embracing the underwater realm, whether to hunt for prey, escape from predators, or simply enjoy the sensation of moving through the water.

Different vertebrates have evolved unique adaptations for swimming, from streamlined bodies to powerful muscles and specialized respiratory systems. Each species has its own style of swimming, perfectly suited to its habitat and lifestyle. For instance, a mighty whale effortlessly cruises through the vast oceans, while a nimble fish zips through intricate coral reefs.

Burrowing

Burrowing is a locomotion method where animals dig into soil, sand, or other substrates to move, hide, or nest. It involves using limbs, claws, heads, or bodies to excavate, often aided by muscular contractions or specialized adaptations like sharp nails or streamlined shapes.

This method suits environments where surface exposure risks predation or extreme conditions, offering protection and access to food (e.g., worms or roots). Burrowing can be shallow (e.g., temporary shelters) or deep (e.g., complex tunnel systems), depending on the species and purpose.

Burrowing varies among vertebrates. Mammals like moles (Eulipotyphla) dig with spade-like claws, and rodents like gophers (Rodentia) use teeth and claws for burrow networks. Reptiles such as sandfish lizards (Squamata) “swim” through sand with body movements. Amphibians like caecilians (Gymnophiona) burrow using worm-like bodies and head thrusts. Fish like mudskippers (Perciformes) dig into mud with fins, highlighting burrowing’s versatility across habitats.

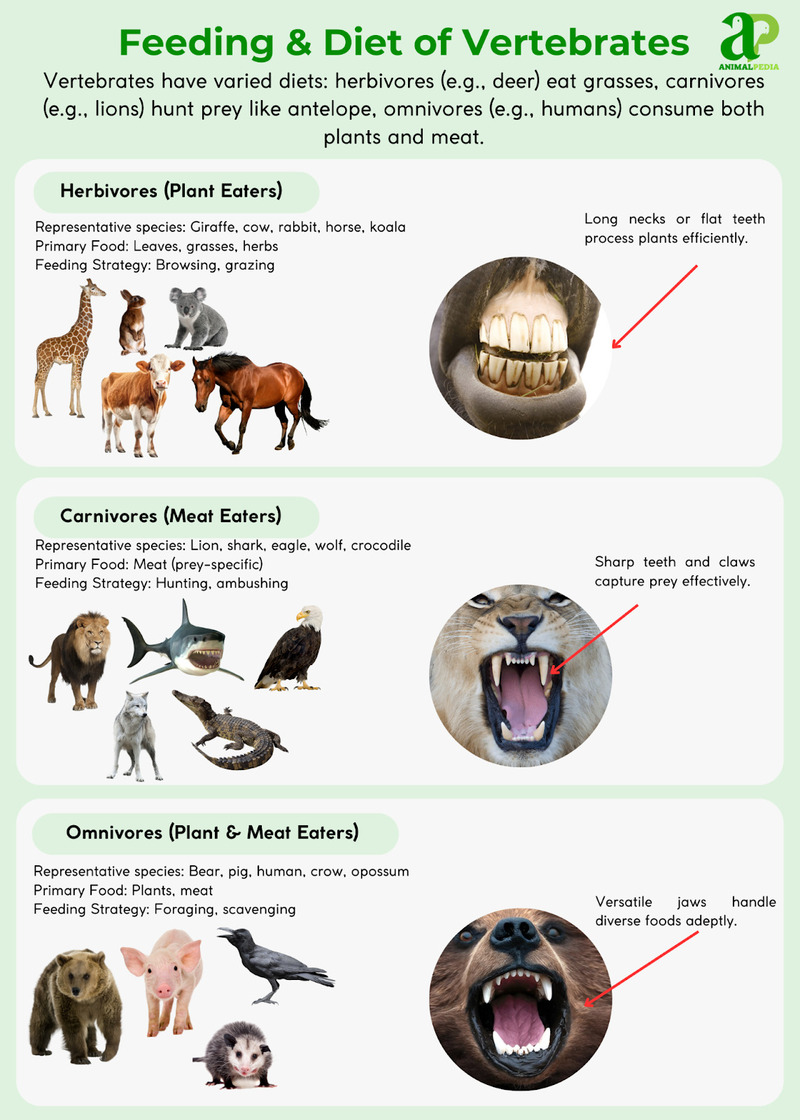

Diet & Feeding

Vertebrates exhibit diverse diets: herbivores (e.g., deer) eat plants, favoring grasses or leaves; carnivores (e.g., lions) consume meat, targeting prey like antelope; omnivores (e.g., humans) eat both. Carnivores may attack humans if threatened or starved, though this is rare. Diet varies by age—juvenile fish (e.g., salmon fry) eat plankton, while adults hunt smaller fish. Young crocodiles target insects, maturing to larger prey like mammals.

Sex and maturity influence feeding: male lions hunt large game, females often coordinate, and cubs scavenge. Eating processes differ—snakes swallow prey whole, lions tear meat into chunks, and herbivores chew plant matter. Swallowing oversized prey risks choking or injury, as seen in pythons. Seasonal shifts occur: bears fatten on berries in fall, then hibernate, while deer switch to bark in winter when greens dwindle. These adaptations reflect ecological and physiological demands across vertebrate taxa.

Defense

Vertebrates employ diverse defense mechanisms to protect themselves. Mammals like skunks use chemical deterrence (spraying odor), while porcupines deploy sharp quills. Reptiles such as turtles rely on bony shells, and snakes may use venom or camouflage. Birds like owls blend into surroundings with cryptic plumage, whereas amphibians (e.g., poison dart frogs) secrete toxins. Fish, such as pufferfish, inflate to deter predators or wield spines for physical defense. These strategies reflect evolutionary adaptations to specific threats.

Differences in defense can vary by age, sex, or maturity, though diet-related questions seem misplaced here. Young vertebrates, like fawns, often hide, while adults (e.g., stags) use antlers. Males and females may differ—male peacocks flaunt tails to intimidate, females less so. The eating process ties to defense indirectly: carnivores tear prey into manageable pieces, but swallowing oversized items risks vulnerability (e.g., a python mid-meal). Seasonal changes influence defense availability—hibernating bears rely on fat reserves, not active defense, in winter. These mechanisms highlight vertebrates’ dynamic survival tactics.

Social structures

Vertebrate social structures vary widely. Mammals like wolves form tight-knit packs with cooperative hunting, while solitary tigers roam independently, meeting only to mate. Birds such as penguins live in colonies for breeding, contrasted by territorial eagles. Reptiles (e.g., lizards) are often solitary, though some turtles nest communally. Amphibians like frogs may aggregate during mating season, otherwise remaining alone. Fish range from schooling sardines to solitary sharks, reflecting ecological pressures.

Social hierarchies shape group dynamics. In wolf packs, an alpha pair leads, enforcing order through dominance displays. Primates like baboons exhibit ranked systems based on strength or kinship, with males often vying for top status. Territorial behavior is pronounced—lions mark boundaries with scent, birds defend nests via song or combat, and reptiles like komodo dragons patrol ranges aggressively. These structures and behaviors optimize survival and reproduction across taxa.

How do Vertebrates reproduce?

Vertebrates reproduce via various methods, including asexual and sexual reproduction. Some vertebrates are hermaphrodites, while others show sexual dimorphism. Reproductive cycles and seasonality also play a role.

Moreover, many vertebrates provide parental care and have intriguing ways of offspring development.

Asexual Reproduction

Asexual reproduction is a unique method found in some vertebrates where a single parent can produce offspring without the need for a mate. This process can occur through methods like budding, fragmentation, or parthenogenesis.

Budding involves a new individual developing as an outgrowth from the parent organism. Fragmentation refers to the parent organism splitting into pieces, each capable of developing into a new individual. Parthenogenesis is when an unfertilized egg develops into a new individual without any genetic contribution from a male.

Although asexual reproduction is less common in vertebrates compared to other organisms like bacteria or plants, certain species such as certain lizards, fish, and amphibians can still utilize this method.

It highlights the various ways vertebrates have evolved to ensure their survival and reproduction without the need for a mate.

Sexual Reproduction

When it comes to reproduction in vertebrates, sexual reproduction stands out as a vital process. This intricate method involves the merging of specialized cells, known as gametes, from a male and female individual. By combining these gametes, a unique offspring with a diverse set of genetic traits is created.

In vertebrates like fish, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals, sexual reproduction plays a crucial role in ensuring genetic variability within the species.

During sexual reproduction, male vertebrates produce sperm that carries genetic material, while female vertebrates produce eggs. The fusion of these two gametes through fertilization results in the formation of a zygote, which eventually develops into a new individual.

This process is essential for genetic diversity, which ultimately contributes to the survival and evolution of vertebrate species. Each species has evolved specific mating and reproductive behaviors, along with adaptations and strategies geared towards achieving successful reproduction.

From intricate courtship displays to elaborate mating rituals, vertebrates have developed a diverse array of methods to pass on their genes and maintain the survival of their species.

Hermaphroditism and Sexual Dimorphism

Hermaphroditism and sexual dimorphism offer fascinating insights into how vertebrates reproduce, showcasing the diverse ways these organisms ensure the continuation of their species.

Hermaphroditism, observed in certain fish, amphibians, and invertebrates, allows an individual to possess both male and female reproductive organs. This unique trait grants them the flexibility to mate with any suitable partner encountered, significantly increasing their reproductive success.

Conversely, sexual dimorphism refers to the distinct physical differences between males and females of the same species. These differences can range from size variations to unique coloration or specialized features that aid in attracting or competing for mates. Such variations play a crucial role in courtship behaviors and mate selection within vertebrate populations.

Reproductive Cycles and Seasonality

Each type of vertebrate, from mammals like cats and dogs to birds and fish, has its unique way of reproducing.

Some have specific breeding seasons, while others can reproduce year-round. Mammals typically have a gestation period before giving birth, birds lay eggs that require incubation, and fish may release eggs for external fertilization.

Reptiles like turtles bury their eggs in sand or soil to ensure the survival of their offspring. It’s fascinating to observe the varied methods nature has designed for reproduction among vertebrates, showcasing the beauty and diversity of the animal kingdom.

Parental Care and Offspring Development

Vertebrates exhibit varied parental care. Birds like eagles build nests and provision chicks, while mammals (e.g., elephants) nurse and protect young for years. Reptiles such as crocodiles brood eggs, guarding hatchlings, though many lay eggs and leave. Amphibians (e.g., poison frogs) may carry tadpoles to water, and some fish (e.g., seahorses) feature male brooding.

Parental investment trades off with reproductive output—high care (e.g., mammals) boosts offspring survival but limits litter size, enhancing evolutionary fitness. Offspring development varies: direct development (e.g., reptiles) yields mini-adults, while indirect (e.g., amphibians) involves larval stages and metamorphosis. Ecologically, these strategies—seen in nurturing wolves or metamorphosing frogs—reflect adaptations to predation, habitat, and resource pressures, driving vertebrate diversity.

Anatomy

Vertebrates possess intricate anatomical systems vital for survival. Below is a brief overview of five key systems:

- Respiratory System: Vertebrates use lungs or gills for breathing. Oxygen enters the blood, and carbon dioxide is expelled via alveoli or gill filaments.

- Circulatory System: The heart pumps blood through a closed network of vessels. Oxygenated and deoxygenated blood are separated in advanced species.

- Digestive System: Food is processed by enzymes in the stomach and intestines, with waste expelled through the anus.

- Excretory System: Kidneys filter waste into urine, maintaining water-salt balance, expelled via bladder or cloaca.

- Nervous System: The brain and spinal cord coordinate responses, with peripheral nerves enabling complex behaviors.

These systems work together seamlessly, showcasing the adaptability of vertebrates across diverse environments.

What is the relationship between Vertebrates and Humans?

Vertebrates and humans are intricately linked through evolution, ecology, and science. As fellow vertebrates, humans rely on these animals for survival, knowledge, and ecosystem stability, though interactions can be beneficial or harmful depending on context.

Evolutionary Connection

Humans, as vertebrates, share a backbone and nervous system with this group, a beneficial bond from a shared ancestor 500 million years ago (Shubin, 2008, Your Inner Fish). This lineage enabled human traits like upright posture and cognition.

Fossil records, like the 375-million-year-old Tiktaalik, show vertebrates transitioning to land, shaping human anatomy. The National Academy of Sciences (2019) notes 99% of human genes align with other vertebrates, driving evolutionary biology research.

Ecological Dependence

Vertebrates sustain humans ecologically—70% of global food protein comes from fish and livestock (FAO, 2022). Birds and bats pollinate 35% of crops (Klein et al., 2007, Ecology Letters).

Humans farm or hunt these species, but overfishing depletes 33% of marine vertebrates (WWF, 2021), harming biodiversity. This interaction supports human life yet risks ecological collapse if unmanaged.

Medical Advancements

Vertebrates like mice, sharing 85% of human genes, are vital for medical breakthroughs (NIH, 2020). Over 60% of drugs are tested on them (Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2018).

Labs use these models to mimic human diseases, advancing treatments, though 95 million vertebrates are used yearly, raising ethical issues (Taylor et al., 2019, Alternatives to Laboratory Animals). This relationship drives health progress but challenges animal welfare.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Vertebrates Regrow Lost Limbs or Body Parts?

Yes, you’re right! Some vertebrates like certain lizards, salamanders, and even some fish possess the ability to regrow lost limbs or body parts through a process called regeneration. It’s truly fascinating!

Do All Vertebrates Have the Same Number of Bones?

No, not all vertebrates have the same number of bones. Each species has adapted differently, resulting in varying bone structures. Evolution and environmental pressures play a significant role in determining the bone count across different vertebrate groups.

Are There Any Vertebrates That Are Immune to Cancer?

Yes, some vertebrates are immune to cancer. Sharks are an example. Their genetic makeup and unique immune system contribute to their ability to resist this disease. It’s fascinating how nature has its ways.

Can Vertebrates Be Trained to Communicate With Humans?

Yes, vertebrates can be trained to communicate with humans. Various studies have shown that certain species such as dolphins, parrots, and apes can learn to understand and respond to human language cues through training programs.

How Do Vertebrates Adapt to Extreme Environments?

You adapt to extreme environments by evolving specialized features like thick fur, insulating blubber, or efficient cooling mechanisms. Your body adjusts to handle temperature extremes, lack of oxygen, or intense pressure for survival.

Conclusion

To wrap up, vertebrates are fascinating animals with a wide range of characteristics, behaviors, and anatomical features. From crawling and swimming to burrowing and reproducing, vertebrates showcase the incredible diversity of life on Earth. Whether you’re studying fish, birds, mammals, or reptiles, there is always something new and exciting to learn about these amazing creatures. So next time you come across a vertebrate, take a moment to appreciate the wonders of the animal kingdom!