Alligators, scientifically Alligator mississippiensis (American alligator) and Alligator sinensis (Chinese alligator), are large reptiles known for their robust build and powerful jaws. They inhabit southeastern U.S. wetlands (A. mississippiensis) and China’s Yangtze River basin (A. sinensis). Their key feature, size, sees A. mississippiensis reaching 11–15 feet (3.4–4.6 meters) and 500–1,000 pounds (227–454 kilograms), while A. sinensis is smaller, at 5–7 feet (1.5–2.1 meters) and 80–100 pounds (36–45 kilograms).

As apex predators, alligators dominate their ecosystems. They ambush prey, using stealth and explosive lunges, targeting fish, turtles, birds, and mammals. Their diet adapts to availability: juveniles eat insects, while adults eat larger prey. Human interactions often involve conflict due to habitat overlap, requiring careful management.

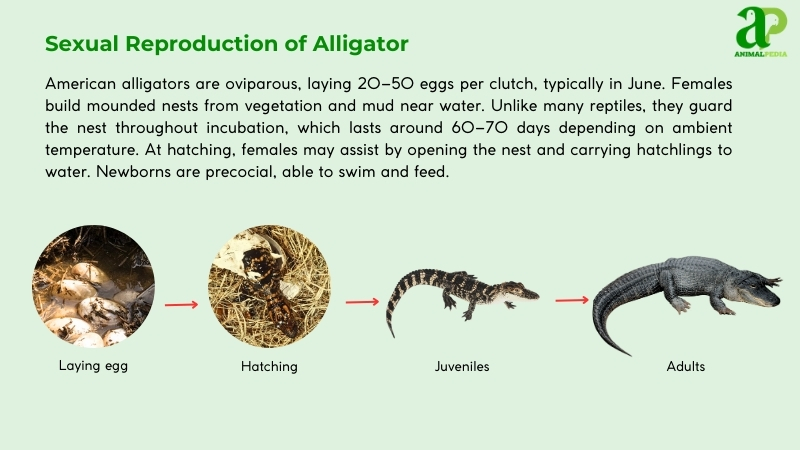

Reproduction begins in spring. Males attract females through vocalizations, such as bellowing, and through head-slapping displays. After mating, females build mound nests from vegetation and lay 20–50 eggs, each weighing 0.2–0.3 pounds (0.09–0.14 kilograms). The incubation period lasts about 60–65 days, and nest temperature determines the sex of the hatchlings. Newborn alligators are 9–10 inches (23–25 centimeters) long and stay near their mothers for up to two years for protection.

In the wild, alligators live 35-50 years, while some individuals in captivity live over 70 years. They shape their environments by digging “gator holes,” which retain water during dry periods and provide refuge for other wildlife. Despite their ancient lineage and ecological value, human-wildlife conflict and habitat destruction continue to pose conservation challenges.

This article delves into alligator appearance, habitats, behaviors, and ecological roles, offering insights into their predatory prowess and conservation needs.

What Does The Alligator Look Like?

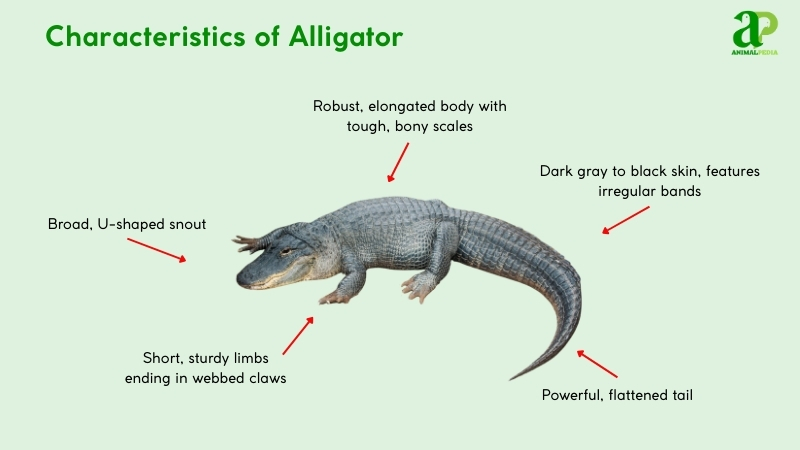

Alligators, primarily Alligator mississippiensis (American alligator), exhibit a robust, elongated body, typically 11–15 feet (3.4–4.6 meters) long and 500–1,000 pounds (227–454 kilograms). Their dark gray to black skin, with occasional olive or brown hues, features a camouflage pattern of irregular bands, ideal for murky wetlands. The skin’s tough, bony scales (osteoderms) provide armor, with a rough, pebbled texture, unlike the smoother hides of other characteristics of reptiles (Mazzotti et al., 2019).

From head to tail, alligators have distinct features: a broad, U-shaped snout houses sharp teeth and nostrils for breathing while submerged. Their small, yellow-green eyes, with vertical pupils, sit high for aquatic vision. The muscular neck supports a heavy head, leading to a cylindrical body with short, sturdy limbs ending in webbed claws for swimming.

The powerful, flattened tail, which accounts for half their length, propels them through water at 20 mph (32 km/h). Compared to crocodiles (Crocodylus acutus), alligators have broader snouts and darker coloration, with less visible lower teeth when jaws close, distinguishing them in shared habitats like Florida’s Everglades (Platt et al., 2018).

How Big Do Alligator Get?

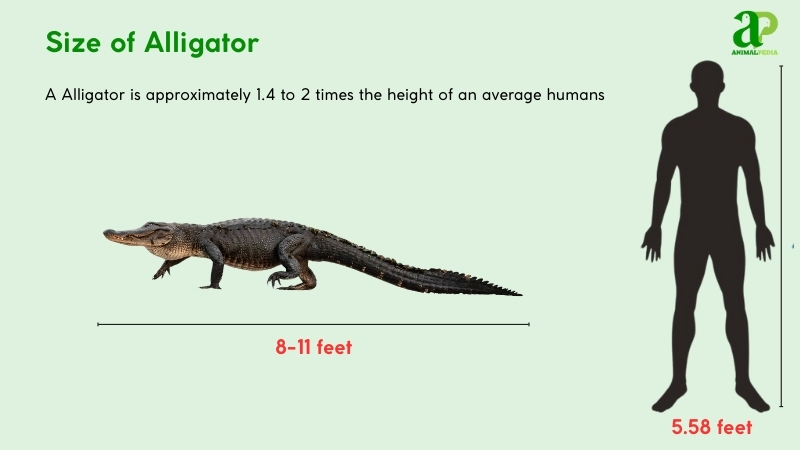

Alligators, specifically Alligator mississippiensis, average 8–11 feet (2.4–3.4 meters) in length and 400–800 pounds (181–363 kilograms) for males, while females reach 6–9 feet (1.8–2.7 meters) and 200–400 pounds (91–181 kilograms). These measurements reflect adults in southeastern U.S. wetlands, with size varying by habitat and diet (Mazzotti et al., 2019).

The largest recorded alligator, found in Louisiana in 2014, measured 19.2 feet (5.8 meters) and weighed 2,000 pounds (907 kilograms), per the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

Males typically outsize females by 2–3 feet (0.6–0.9 meters) and 200–400 pounds (91–181 kilograms), due to sexual dimorphism favoring male growth for territorial dominance.

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 8–11 ft (2.4–3.4 m) | 6–9 ft (1.8–2.7 m) |

| Weight | 400–800 lb (181–363 kg) | 200–400 lb (91–181 kg) |

What Are The Unique Physical Characteristics Of The Alligator?

Alligators, notably Alligator mississippiensis, possess unique physical traits that distinguish them from other crocodilians. Their broad, U-shaped snout and osteoderms (bony plates) embedded in thick, armored skin set them apart. Unlike crocodiles, the lower teeth of alligators are hidden when the jaws close, a trait exclusive to the genus Alligator (Mazzotti et al., 2019).

The U-shaped snout, wider than the V-shaped snout of crocodiles, supports powerful biting for crushing prey, such as turtles, exerting an alligator bite force of up to 2,980 pounds (1,352 kilograms). Osteoderms, unique to alligators and crocodilians, form a dorsal shield that enhances defense against predators.

These plates, rich in collagen, grow with the animal and reach 11–15 feet (3.4–4.6 meters) in males. Recent studies highlight the snout’s sensory pits, which detect pressure changes in water, aiding ambush hunting. This adaptation, absent in most reptiles, optimizes their role as apex predators in wetlands (Platt et al., 2018).

How Does an Alligator Adapt With Its Unique Features?

Alligators, notably the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), thrive in wetlands due to their distinctive U-shaped snout and osteoderms. The broad snout crushes prey like turtles, while osteoderms shield against predators, ensuring survival in swamps and rivers (Mazzotti et al., 2019).

Their senses enhance adaptation. Powerful jaw muscles deliver bites of up to 2,980 pounds (1,352 kilograms) to secure prey. Sensory pits on the snout detect water vibrations, aiding ambush hunting. Keen eyesight with vertical pupils enables tracking movement in low light, thereby improving nocturnal predation. Acute hearing perceives low-frequency sounds, alerting them to threats. A strong tail propels swimming at 20 mph (32 km/h), facilitating escapes and pursuits (Platt et al., 2018).

Anatomy

Alligator anatomy supports their role as apex predators. Their respiratory, circulatory, digestive, excretory, and nervous systems are adapted for aquatic and terrestrial life, enhancing hunting efficiency and environmental resilience (Mazzotti et al., 2019).

- The respiratory system, specifically the lungs, facilitates unidirectional airflow to maximize oxygen intake. Nostrils on the snout allow breathing while submerged, supporting prolonged dives during hunts.

- Circulatory System: A four-chambered heart separates oxygenated blood, boosting stamina. Valves enable diving by redirecting blood from the lungs, conserving energy.

- Digestive System: A muscular gizzard and acidic stomach break down bones and shells. A slow metabolism allows for weeks between meals, optimizing energy use.

- Excretory System: Kidneys filter waste, excreting uric acid to conserve water. Cloacal storage minimizes water loss in brackish habitats.

- Nervous System: A large brain coordinates sensory input from snout pits and eyes. Rapid reflexes enhance ambush predation and threat response.

Together, these anatomical systems equip alligators to dominate both in water and on land. Their physiology balances power, endurance, and sensory precision, enabling them to thrive in complex ecosystems. These traits not only define their survival strategy but also reinforce their ecological role as top-tier predators in wetland food webs.

How Many Types Of Alligators are there?

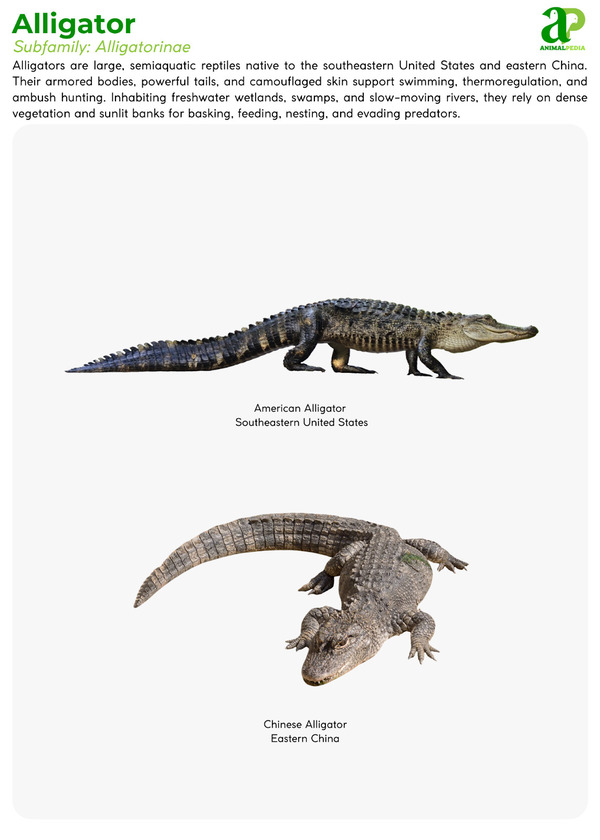

There are two recognized species of alligator: Alligator mississippiensis (American alligator) and Alligator sinensis (Chinese alligator). These species belong to the family Alligatoridae, which also includes several caiman species. Despite being related, only these two species belong to the genus Alligator.

The classification of alligators is rooted in modern phylogenetics, which analyzes evolutionary relationships through comparative anatomy and molecular data. This taxonomic framework was refined by evolutionary biologists using DNA sequencing technologies and cladistic analysis (Oaks, 2011). It aligns with the broader Crocodylia order, which includes crocodiles and gharials.

Order: Crocodylia

└── Family: Alligatoridae

└── Genus: Alligator

├── Species: Alligator mississippiensis (American Alligator)

└── Species: Alligator sinensis (Chinese Alligator)

No special cases complicate Alligator classification, unlike crocodiles, where hybridization occurs. A. mississippiensis inhabits U.S. wetlands, while A. sinensis, a critically endangered species, is restricted to China’s Yangtze basin. Their distinct ranges and genetic divergence confirm clear species separation, with no recognized subspecies (Platt et al., 2018).

Where Do Alligators Live?

Alligators, primarily Alligator mississippiensis, inhabit southeastern U.S. wetlands, concentrated in Florida’s Everglades, Louisiana’s bayous, and Texas’s coastal marshes. Alligator sinensis resides in China’s Yangtze River basin. These regions feature freshwater swamps, marshes, and slow-moving rivers, ideal for their aquatic lifestyle.

The warm, humid environment, with temperatures of 75–95°F (24–35°C), supports their ectothermic metabolism. Abundant water and dense vegetation provide ambush-hunting grounds and nesting sites, while prey such as fish and birds sustain their diet. Alligators have inhabited these areas since the Miocene, about 23 million years ago, with no significant migration. Their distribution reflects adaptation to stable, prey-rich wetlands, as indicated by fossil records and ecological studies (Platt et al., 2018).

How Do Seasonal Changes Affect Their Behavior?

Alligators, primarily Alligator mississippiensis, exhibit behaviors across two main seasons: warm (April–October) and cool (November–March) in their southeastern U.S. habitats. These shifts optimize survival in wetlands (Mazzotti et al., 2019).

- Warm Season (April–October): Alligators are active, hunting fish and mammals, mating, and nesting. Females lay 20–50 eggs in June, guarding nests vigilantly.

- Cool Season (November–March): Activity drops; alligators enter brumation, staying in burrows or water with minimal feeding. They bask on sunny days to regulate body temperature.

These seasonal behavioral adaptations highlight the alligator’s ability to synchronize biological rhythms with environmental cues. By conserving energy during cooler months and maximizing reproductive and feeding activities in warmer periods, alligators maintain ecological balance and ensure long-term survival in dynamic wetland ecosystems.

What Is The Behavior Of an Alligator?

Alligators, primarily Alligator mississippiensis, exhibit complex behaviors that cement their role as apex predators in wetlands. Their actions, from hunting to communication, reflect adaptations to aquatic environments, ensuring survival and ecological balance (Mazzotti et al., 2019).

- Feeding Habits: Alligators ambush prey—fish and mammals —using powerful jaws. Juveniles eat insects, while adults consume larger vertebrates.

- Bite & Venomous: Their bite delivers 2,980 pounds (1,352 kilograms) of force, crushing bones. Alligators lack venom and rely on physical strength.

- Daily Routines and Movements: Active at dusk, they bask daily to regulate temperature. They travel 1–2 miles (1.6–3.2 kilometers) for food or mates.

- Locomotion: They swim at 20 mph (32 km/h) using strong tails. On land, they crawl or high-walk slowly.

- Social Structures: Mostly solitary, they form loose groups during mating. Females protect young for 1–2 years.

- Communication: Bellowing and head-slapping signal mates or territory. Subaudible vibrations coordinate group behavior.

These behaviors highlight alligators’ predatory prowess. Their feeding habits, critical for ecosystem balance, merit deeper exploration.

What Do Alligators Eat?

Alligators, primarily Alligator mississippiensis, are carnivorous, feeding on fish, turtles, birds, and mammals, with a preference for garfish and raccoons. Human attacks are rare, occurring only when provoked or near water. Alligators crush their prey with 2,980 pounds (1,352 kilograms) of jaw force, swallowing small items whole or tearing larger ones apart. Oversized prey can cause injury or regurgitation, as their stomachs are unable to handle it (Wilkinson et al., 2016).

- Diet by Age:

Juveniles (<4 feet/1.2 meters) primarily consume insects, amphibians, crustaceans, and small fish due to limited jaw strength and size. As they grow, subadults shift to turtles, snakes, and wading birds. Adults (>6 feet/1.8 meters) leverage their powerful bite force—up to 2,980 psi—to tackle larger prey such as deer, muskrats, and even invasive species like nutria, helping maintain ecosystem balance.

- Diet by Gender:

Males and females have broadly overlapping diets, but larger males—being more dominant—often secure high-calorie prey such as wild boar or large birds. Males also have larger home ranges, which increases access to a diverse range of prey types. In contrast, nesting females may be closer to water bodies and feed on more readily available, smaller prey, such as fish and amphibians, to reduce energy expenditure and protect their nests.

- Diet by Seasons:

During warm months (April–October), increased metabolic rates and prey availability lead to more frequent feeding. In the cool season (November–March), they undergo brumation—similar to hibernation—greatly reducing activity and food intake. They may opportunistically consume slow-moving or weakened animals but largely rely on stored fat reserves accumulated during the active season.

How Do Alligator Hunt Their Prey?

Alligators rely on their incredible patience and stealth to catch their prey. These impressive predators often hide near the water’s edge, camouflaged by debris or plants. They keep only their eyes and nostrils above the surface, scanning for any unsuspecting prey that comes close.

When the moment is right, they swiftly attack, using their powerful jaws to seize their prey and pull it into the water.

These skilled hunters mainly eat fish, turtles, birds, and mammals that approach the water’s edge. Alligators are opportunistic eaters, meaning they’ll take advantage of any prey within their reach.

Their hunting technique involves a mix of patience, stealth, and sudden bursts of speed to get a meal.

In the wild, alligators play a vital role in maintaining the balance of their ecosystem. Their hunting skills showcase their ability to adapt and survive in their natural habitat, showing their importance in the food chain.

“Adaptability and patience are key traits of alligators in hunting for survival in their environment,” says wildlife expert Dr. Smith.

Are Alligator Venomous?

Alligators don’t possess venom like some snakes do. Instead of relying on venom to subdue their prey, alligators use their strong jaws and sharp teeth to catch and consume their meals. With a bite force, they can easily crush bones and tear through flesh.

These reptiles have a unique hunting strategy that doesn’t involve venom. They’re patient and stealthy predators, often lurking underwater, waiting for the perfect moment to strike. When the time is right, they swiftly lunge forward, using their powerful jaws to ambush unsuspecting prey.

Alligators demonstrate impressive hunting skills without venom, making them formidable predators in their natural habitat.

Their ability to strike with precision and force highlights the adaptability and strength of these fascinating creatures.

When Are Alligator Most Active During The Day?

Alligators are most active during the day when the sun is high in the sky. They love to bask in the sunlight and soak up the warmth, especially in the early morning and late afternoon. This is when you’ll often see them swimming around, hunting for food, or simply enjoying a leisurely stroll by the water’s edge.

Alligators showcase their impressive swimming skills and powerful bodies during these daylight hours.

You may spot them gracefully floating in the water with their eyes and nostrils above the surface, or stealthily lurking near the shore, waiting for the perfect opportunity to catch prey. Witnessing these magnificent creatures in action during the day is truly a sight.

How Do Alligators Move On Land And Water?

Alligators are truly creatures that excel in both land and water environments. On land, they’re adept at walking, running, and climbing using their powerful legs and muscular tails for balance and speed. Their agility and grace on land are a testament to their evolutionary adaptations.

However, it’s in the water where alligators truly shine as extraordinary swimmers. Their streamlined bodies and webbed feet enable them to glide effortlessly through the water, reaching impressive speeds of up to 20 miles per hour when necessary. Alligators can also be submerged for extended periods, breathing through their nostrils while mostly hidden from view.

Whether traversing land or water, alligators demonstrate a sense of purpose and independence in their movements. Their strategic and deliberate actions highlight their finely tuned survival instincts, honed over millions of years of evolution. Their ability to thrive in diverse environments showcases their adaptability and resilience as apex predators.

Next, let’s delve into whether alligators prefer a solitary lifestyle or living in groups.

Do Alligator Live Alone Or In Groups?

In the diverse habitats they inhabit, alligators exhibit interesting social behaviors that challenge the idea of solitary predators. Despite common beliefs, alligators aren’t always solitary creatures. They can be surprisingly social, especially at certain times of the year.

While alligators usually hunt alone, they may gather in groups known as congregations. These gatherings are more frequent in warmer months and offer benefits like increased mating opportunities and enhanced protection against potential dangers.

During the mating season, male alligators often carve out small territories and create loud bellows to attract females. This behavior can result in large groups of alligators coming together in a specific area.

After mating, the female will construct a nest and guard her eggs until they hatch. During this period, she becomes more social, ensuring the safety of her young offspring.

Alligators, typically seen as solitary predators, exhibit surprising social behaviors that highlight the complexities of their interactions within their ecosystem.

How Do Alligators Communicate With Each Other?

Alligators communicate primarily through vocalizations and body language. Their deep, resonant bellows can be heard over long distances, serving as signals to other alligators in the vicinity. During the breeding season, male alligators use these bellows to mark their territories and attract potential mates.

Along with vocalizations, alligators use body language to convey messages. They may slap their tails on the water or engage in intricate courtship displays to express their intentions.

Even when basking in the sun, alligators communicate through their body movements. By positioning themselves in specific ways or making particular gestures, they can communicate dominance or submission within their social groups.

These behaviors play a crucial role in maintaining social hierarchies and reducing conflicts among alligators. Ultimately, these communication methods are essential for alligators to navigate their environment effectively and interact with each other in a structured manner.

How Do Alligator Reproduce?

Alligators, primarily Alligator mississippiensis, reproduce sexually through internal fertilization. Their reproductive strategy ensures survival in wetland ecosystems.

Breeding begins in spring (April–May). Males bellow and perform head-slapping displays to attract females, while females respond with softer vocalizations. Courtship involves nuzzling and bubble-blowing, leading to mating in water. Both sexes may mate with multiple partners.

Post-mating, females lay 20–50 eggs in June, each weighing 0.2–0.3 pounds (90–140 grams). Eggs are deposited in mound nests of vegetation and mud, protected by the female, who guards against predators like raccoons. Males leave after mating. Environmental stressors, like flooding or drought, can disrupt egg-laying, reducing clutch size.

Eggs incubate for 60–65 days, with nest temperature (86–93°F/30–34°C) determining sex. Hatchlings, measuring 9–10 inches (23–25 centimeters), emerge in August–September and stay near their mother for 1–2 years. They feed on insects and small fish, growing approximately 1 foot (30 centimeters) annually until they reach maturity at 6–8 years.

The alligator life cycle spans 35–50 years, with captives reaching 70 years. Their reproductive success supports wetland biodiversity, but habitat loss threatens breeding grounds (Wilkinson et al., 2016).

How Long Do Alligator Live?

Alligators, primarily Alligator mississippiensis, have a life cycle spanning 35–50 years in the wild, with captives reaching 70 years due to controlled environments and veterinary care. Their longevity supports the stability of wetland ecosystems, although alligator lifespan is influenced by factors such as habitat quality, predation, disease, and human interference.

Lifespan varies slightly by species, with Alligator mississippiensis living longer than Alligator sinensis. Both sexes show similar longevity, though some studies suggest females may live marginally longer, possibly due to lower risk-taking behaviors.

Juvenile survival rates are low because of birds and larger alligators, but once maturity is reached—around age 6 to 8—adults face few natural threats, reinforcing their apex predator status. Conservation efforts are critical to maintain their populations and ecological roles (Mazzotti et al., 2019).

What Are the Threats or Predators That Alligators Face Today?

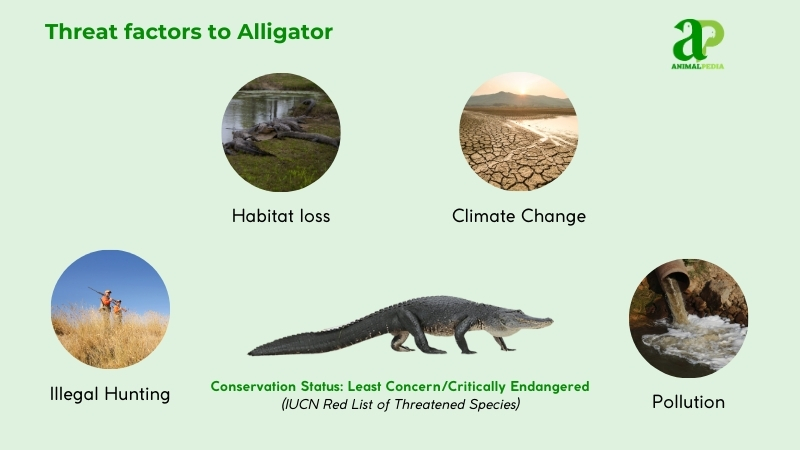

Alligators, primarily Alligator mississippiensis, face threats that challenge their survival in wetlands. Habitat loss, pollution, climate change, and illegal hunting are primary concerns, while predators target mostly juveniles. Human activities exacerbate these risks, necessitating conservation efforts.

- Habitat Loss: Urbanization and agriculture have destroyed 20% of the U.S.’s wetlands, reducing breeding and feeding grounds and limiting population growth.

- Pollution: Pesticides and heavy metals impair reproduction and health, with 15% of alligator eggs showing contamination effects.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures and sea levels alter nesting sites, potentially shifting sex ratios, as warmer nests produce more males.

- Illegal Hunting: Poaching for skins reduces populations, though regulated hunting has had less of an impact since the 1980s.

Predators include birds (e.g., herons, eagles), which prey on hatchlings (<2 feet/0.6 meters), and larger alligators, which cannibalize smaller ones. Adult alligators, as apex predators, face few natural threats.

Human impacts are significant. Wetland drainage for development and pollution from agricultural runoff degrade habitats, and 50% of Florida’s wetlands have been lost since 1900. Poaching persists despite regulations, and human-alligator conflicts rise in urban areas, leading to relocations or culls. Conservation, like habitat restoration, is critical to sustain populations (Platt et al., 2018).

Are Alligator Endangered?

Not all alligators are endangered—Alligator mississippiensis (American alligator) is listed as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), while Alligator sinensis (Chinese alligator) is classified as Critically Endangered due to severe habitat loss and fragmentation (IUCN, 2023).

The American alligator was once endangered due to overhunting and habitat degradation. However, strong conservation efforts, including legal protections and regulated farming, have led to a population rebound. Today, wild populations exceed 5 million individuals, mainly in the southeastern United States—especially Florida and Louisiana (Rosenblatt et al., 2021). Its recovery is considered a landmark success in U.S. wildlife conservation history.

In contrast, the Chinese alligator is under significant threat. Native to the lower Yangtze River, fewer than 300 individuals are known to exist in the wild, according to the latest assessments, while an estimated 20,000 individuals are maintained in managed breeding programs (Wan et al., 2020). Despite intensive reintroduction efforts, the ongoing destruction of wild habitats from urban expansion and agricultural development hinders long-term recovery.

This contrast highlights the roles of region-specific threats and the effectiveness of conservation policy in determining species survival. While A. mississippiensis thrives under active protection, A. sinensis exemplifies the urgency of sustained habitat conservation and ecological restoration.

What Conservation Efforts Are Underway?

American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis), once nearly extinct, thrive due to robust conservation efforts. Key organizations such as the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) have led initiatives since the 1960s, focusing on habitat restoration and regulated harvesting.

The FWC’s Alligator Management Program, active since 1988, monitors populations and restores wetlands. The Nature Conservancy protects marshes, with 7,063 acres preserved in Texas. The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, which has been ongoing since 2000, enhances hydrology, thereby boosting alligator numbers.

The Endangered Species Act (1973) banned unregulated hunting. Florida’s F.S. §379.3751 mandates licenses for farming and hunting, prohibiting feeding wild alligators to prevent human conflicts. CITES Appendix II (1979) regulates international trade.

Louisiana’s ranching program collects wild eggs, returning 10% of the juveniles to the wetlands, which sustains 3–4 million alligators. Florida’s farming, started in the 1890s, produced 267,065 harvested alligators in 2024, valued at $56 million. These programs increased populations from near extinction in 1967 to “least concern” by 1987.

Success stories include Florida’s $ 14 million industry, which supports sustainable hunting and tourism. Alligators now stabilize ecosystems as keystone species, proving conservation’s impact (Elsey et al., 2019).

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Alligators Be Kept as Pets?

No, you shouldn’t keep alligators as pets. They have specific habitat needs, can be dangerous, and grow large. It’s best to respect their nature in the wild while enjoying them from a safe distance.

Do Alligators Make Good Pets?

You should seriously reconsider the idea of keeping an alligator as a pet. They are not suitable as pets due to their size, aggressive nature, and specific care requirements. Keeping them could pose serious safety risks.

What Is the Lifespan of an Alligator?

An alligator’s lifespan can reach up to 70 years in the wild. In captivity, they may live longer. Proper care is necessary. Remember, respecting their natural habitats is vital for their survival.

Do Alligators Migrate to Different Locations?

Yes, alligators do migrate to different locations. They move to find food, shelter, and more suitable habitats. Migration is a natural behavior that helps alligators adapt to environmental changes and increase their chances of survival.

Are Alligators Territorial Animals?

Yes, alligators are territorial animals. They establish their own space and protect it from others. By marking their territory and displaying aggressive behaviors, they assert dominance and defend their area from potential threats or intruders.

Conclusion

To sum up, alligators are fascinating creatures, characterized by their scaly bodies, powerful jaws, and impressive hunting skills. Living in freshwater habitats, they play an essential role in maintaining ecosystem balance. With their unique adaptations, alligators can thrive both on land and in water, demonstrating their abilities. Next time you see an alligator, remember to admire their strength, agility, and significant place in the natural world!