Caimans, sturdy crocodilians, boast armored bodies with bony plates (osteoderms) and short, muscular tails. Their dark green to brown skin, often mottled, aids camouflage in murky waters. Six Caiman species exist within the family Alligatoridae, genus Caiman, thriving across diverse Neotropical wetlands.

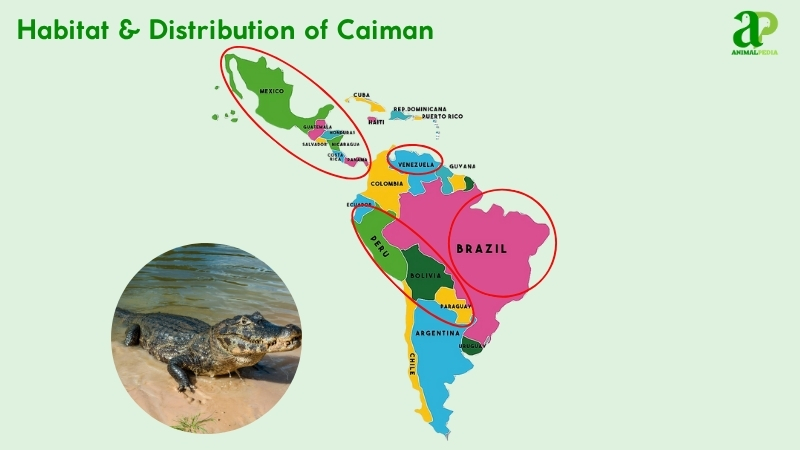

Prominent species include Caiman crocodilus (spectacled caiman), named for bony ridges resembling spectacles, and Caiman yacare (Yacare caiman), known for its robust jaw. The spectacled caiman measures 6–8 feet (1.8–2.4 meters) and weighs 80–120 pounds (36–54 kilograms), while Yacare caimans reach 7–10 feet (2.1–3 meters) and 100–150 pounds (45–68 kilograms). They inhabit Central and South America, from Mexico’s coastal marshes to Bolivia’s Pantanal and Brazil’s Amazon Basin, favoring slow-moving rivers, swamps, and flooded savannas.

Caimans stand out for their adaptability, with size and nocturnal eyes as key features. Their geographic range spans diverse ecosystems, including Venezuela’s Llanos and Peru’s Madre de Dios. Unlike alligators, caimans have narrower snouts, optimizing fish-heavy diets. They are not apex predators but skilled opportunists, ambushing prey like fish, crustaceans, and small mammals. Juveniles target insects, while adults occasionally take capybaras. Human interactions rise in urbanizing areas, causing conflicts and relocations due to habitat loss.

Behaviorally, caimans are nocturnal hunters, using stealth and rapid lunges. Their diet shifts with prey availability, reflecting ecological flexibility. Socially, they are solitary except during mating, with males defending territories. Human encroachment increases risks, necessitating conservation to mitigate conflicts and protect habitats.

Breeding occurs in the wet season (May–August). Males bellow and vibrate to court females, who lay 15–40 eggs in mound nests of mud and vegetation. Eggs, weighing 0.15–0.2 pounds (70–90 grams), incubate for 65–80 days. Hatchlings, 8–10 inches (20–25 centimeters), remain with mothers for months, reaching maturity at 4–7 years. Lifespans average 30–40 years, with some captives living up to 50 years.

This article examines caiman appearance, habitats, behaviors, and ecological roles, highlighting their adaptability and the urgent need for conservation in Neotropical wetlands.

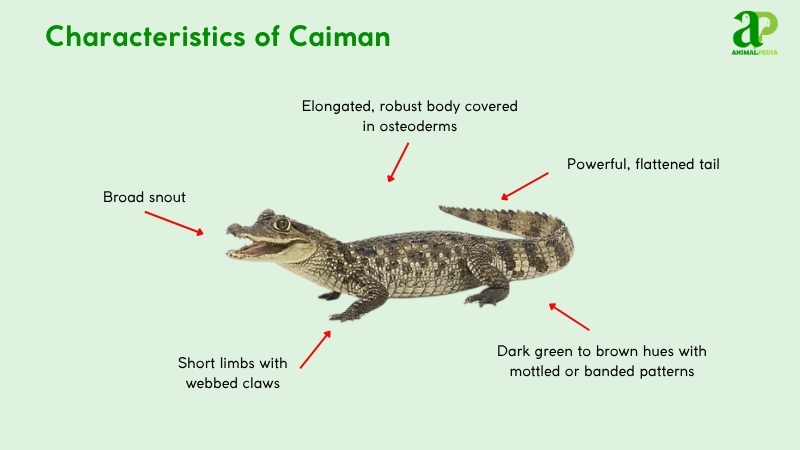

What Do The Caiman Look Like?

Caimans, members of the genus Caiman, have elongated, robust bodies, typically measuring 6–10 feet (1.8–3 meters) in length and weighing 80–150 pounds (36–68 kilograms). Their skin, covered in osteoderms (bony plates), is rough and pebbled, displaying dark green to brown hues with mottled or banded patterns for wetland camouflage.

From head to tail, key features include a broad snout, yellow-green eyes with vertical pupils for nocturnal vision, a short neck, a cylindrical body, short limbs with webbed claws, and a powerful, flattened tail for swimming.

The head houses sensory pits for detecting prey vibrations, while the eyes sit high for aquatic surveillance. The neck is muscular, supporting a heavy skull. The body, armored with scutes, is flexible for maneuvering in water. Limbs enable slow land movement, covering 1–2 miles (1.6–3.2 kilometers) daily.

The tail, which is half their length, propels them through the water at 15 mph (24 km/h). Compared to alligators (Alligator mississippiensis), caimans have narrower snouts and smaller sizes, with spectacled caimans (Caiman crocodilus) showing distinct bony ridges around eyes, unlike the smoother-headed Yacare caiman (Caiman yacare) (Magnusson & Campos, 2019).

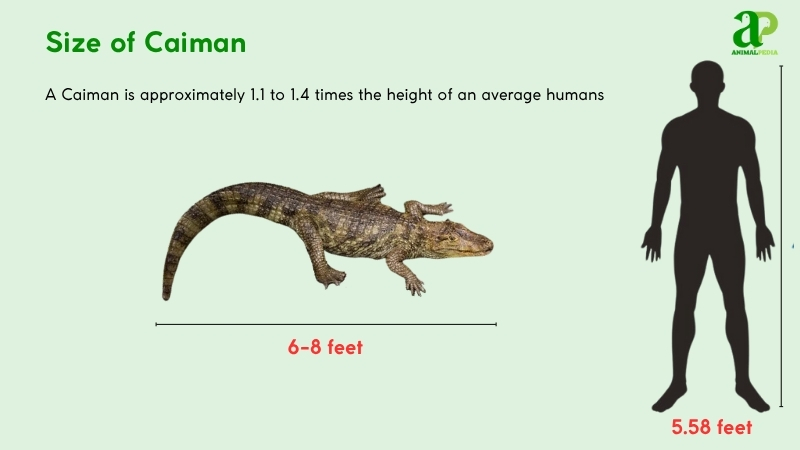

How Big Do Caiman Get?

Caimans, genus Caiman, average 6–8 feet (1.8–2.4 meters) in length and 80–120 pounds (36–54 kilograms) for species like Caiman crocodilus. Yacare caimans (Caiman yacare) may reach 10 feet (3 meters) and 150 pounds (68 kilograms). Adults typically measure 6–10 feet (1.8–3 meters) from snout to tail, depending on species and habitat.

The largest recorded spectacled caiman, found in Brazil’s Pantanal in 2017, stretched 11.5 feet (3.5 meters) and weighed 190 pounds (86 kilograms), per Herpetological Review. Males outsize females by 1–2 feet (0.3–0.6 meters) and 20–40 pounds (9–18 kilograms), reflecting sexual dimorphism for territorial dominance.

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 7–10 ft (2.1–3 m) | 6–8 ft (1.8–2.4 m) |

| Weight | 100–150 lbs (45–68 kg) | 80–110 lbs (36–50 kg) |

What Are The Unique Physical Characteristics Of The Caiman?

Caimans, genus Caiman, possess distinct physical traits within the Alligatoridae family, setting them apart from alligators and crocodiles. Their infraorbital bridge, a bony ridge between the eyes, is uniquely pronounced, especially in Caiman crocodilus (spectacled caiman), resembling a pair of spectacles. Unlike alligators’ broad snouts, caimans have narrower, tapered snouts, optimizing fish-heavy diets in Neotropical wetlands.

The infraorbital bridge enhances skull rigidity, supporting bites of up to 1,000 pounds (454 kilograms) of force, according to biomechanical studies. Their skin, embedded with tightly packed osteoderms, forms a lighter, more flexible armor than that of crocodiles, aiding swift water maneuvers.

Recent research highlights their retinal adaptations, including a high rod-to-cone ratio, which enable superior night vision for nocturnal hunting —a trait less developed in alligators. These features, combined with a compact body (6–10 feet/1.8–3 meters), make caimans agile predators in rivers and swamps (Magnusson & Campos, 2019).

How Does Caiman Adapt With Its Unique Features?

Caimans (genus Caiman) rely on their narrow, tapered snouts to thrive in Neotropical wetlands. This unique feature enables the efficient capture of fish and crustaceans, ensuring their survival in rivers and swamps where Caiman prey is abundant (Magnusson & Campos, 2019).

Their senses enhance adaptation. Sensory pits on the snout detect prey vibrations, enabling precise ambushes. Yellow-green eyes with vertical pupils provide sharp nocturnal vision, aiding night hunting. Acute hearing through external ear flaps locates distant sounds, improving threat detection. A sensitive olfactory system in the nostrils tracks food scents, optimizing foraging in murky waters. These traits collectively make caimans agile predators, well-suited to dynamic aquatic environments (Ross, 2018).

Anatomy

Caimans are crocodilians whose internal anatomy reveals adaptations honed by millions of years of evolution. As members of the Alligatoridae family, their physiological systems are specialized for life in Neotropical wetlands, allowing them to thrive as stealthy apex predators across rivers, swamps, and flooded forests.

- Respiratory System: Lungs with unidirectional airflow maximize oxygen uptake. Nostrils atop the snout enable breathing while submerged, aiding stealthy hunts.

- Circulatory System: A four-chambered heart ensures efficient oxygen delivery. Valves redirect blood during dives, conserving energy in low-oxygen environments.

- Digestive System: A muscular stomach and acidic enzymes digest fish and crustaceans. A slow metabolism allows for longer periods between meals, optimizing energy use.

- Excretory System: Kidneys filter waste products, excreting uric acid to conserve water. The cloaca stores waste and adapts to variable wetland conditions.

- Nervous System: A developed brain processes sensory input from the eyes and snout pits. Quick reflexes enhance ambush predation and threat response.

Together, these internal systems empower caimans to maintain ecological balance in biodiversity-rich wetlands like the Pantanal. Their anatomical precision underpins their survival and dominance in aquatic ecosystems, showcasing the evolutionary ingenuity of crocodilians (Magnusson & Campos, 2019).

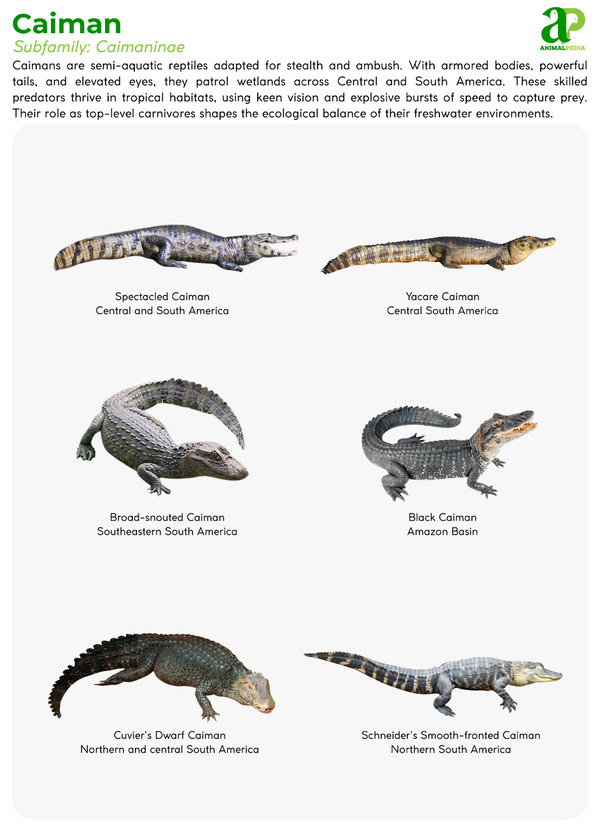

How Many Types Of Caiman?

Six caiman species exist within the genus Caiman, family Alligatoridae, order Crocodilia. These include Caiman crocodilus (spectacled caiman), Caiman yacare (Yacare caiman), Caiman latirostris (broad-snouted caiman), and three less common species: Caiman fuscus, Melanosuchus niger (black caiman), and Paleosuchus palpebrosus (dwarf caiman) (Ross, 2018).

Classification is based on phylogenetic analysis integrating morphology and molecular data, developed by herpetologists such as Medem (1983) and refined through DNA sequencing (Hrbek et al., 2018). This framework distinguishes caimans by snout shape, size, and genetic divergence.

Branch Diagram:

Family: Alligatoridae

└── Subfamily: Caimaninae

├── Genus: Caiman

│ ├── Species: Caiman crocodilus

│ ├── Species: Caiman yacare

│ └── Species: Caiman latirostris

├── Genus: Melanosuchus

│ └── Species: Melanosuchus niger

└── Genus: Paleosuchus

├── Species: Paleosuchus palpebrosus

└── Species: Paleosuchus trigonatus

No special cases complicate Caiman classification, though hybridization between C. crocodilus and C. yacare occurs rarely in overlapping ranges, such as the Pantanal. These hybrids show intermediate traits, challenging taxonomic clarity (Magnusson & Campos, 2019).

Where Do Caiman Live?

Caimans, genus Caiman, inhabit Central and South America, concentrated in Brazil’s Pantanal, Venezuela’s Llanos, and Peru’s Madre de Dios. Spectacled caimans (Caiman crocodilus) dominate Mexico to Bolivia, while Yacare caimans (Caiman yacare) thrive in Paraguay’s wetlands.

Their environment features warm (77–95°F/25–35°C), humid wetlands with slow-moving rivers, swamps, and flooded forests. Dense vegetation and abundant fish support their ambush hunting, and shallow waters suit nesting.

Fossil records indicate caimans have lived here since the Miocene, 23 million years ago, with no significant migration. Their distribution aligns with stable, prey-rich habitats, as indicated by ecological studies (Hrbek et al., 2018).

How Do Seasonal Changes Affect Their Behavior?

Caimans exhibit seasonal behavioral adaptations shaped by the distinct wet and dry periods of Neotropical wetlands. These cyclical shifts influence feeding, reproduction, and thermoregulation, ensuring survival in fluctuating environments.

- Wet Season (May–October): Abundant rainfall expands aquatic habitats, increasing prey availability. Caimans hunt fish and crustaceans more frequently. Females construct nesting mounds along banks, lay eggs, and guard nests from predators.

- Dry Season (November–April): As water levels recede, caimans reduce activity and feeding. They remain in isolated pools, basking frequently to maintain body temperature and conserving energy through limited movement (Magnusson & Campos, 2019).

These behavioral rhythms reflect the caiman’s ecological plasticity, supporting their resilience in the dynamic floodplain systems of South America.

What Is The Behavior Of Caiman?

Caimans, members of the genus Caiman, display a diverse behavioral repertoire shaped by life in fluctuating Neotropical wetlands. Their ecological role as apex predators and keystone species is evident through their daily routines, hunting strategies, and social interactions.

- Feeding Habits: Caimans ambush fish, crustaceans, and small mammals. Juveniles eat insects, adapting to prey availability.

- Bite & Venomous: Their bite exerts 1,000 pounds (454 kilograms) of force, crushing prey. Caimans lack venom and rely on jaw strength.

- Daily Routines and Movements: Nocturnal, they hunt at night and bask daily to regulate temperature. They travel 1–2 miles (1.6–3.2 kilometers) for food.

- Locomotion: They swim at 15 mph (24 km/h) using powerful tails for propulsion. On land, they crawl slowly, covering short distances.

- Social Structures: They are mostly solitary, but form groups during the mating season. Females guard young for months post-hatching.

- Communication: Males bellow to attract mates and establish dominance. Head-slapping and vibrations signal territory or courtship.

These behaviors not only ensure individual survival but also maintain ecosystem balance. Understanding their interactions with prey, rivals, and offspring deepens insight into wetland biodiversity and resilience (Magnusson & Campos, 2019).

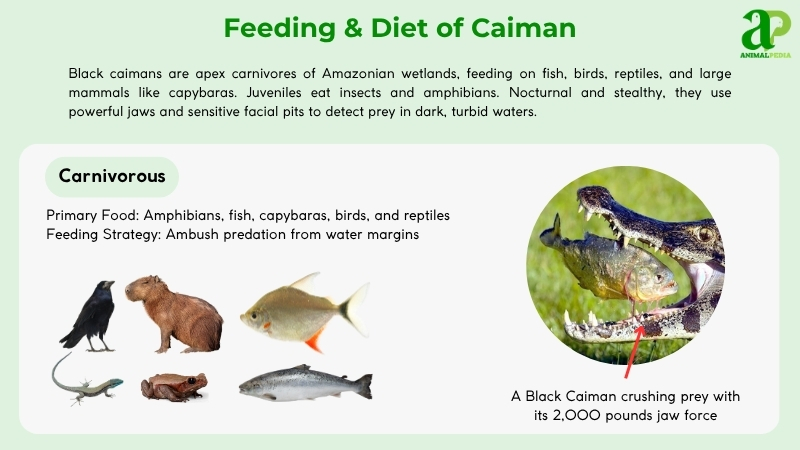

What Do Caiman Eat?

Caimans are carnivores that prey on fish, crustaceans, and small mammals, with a particular preference for piranhas and crabs. Human attacks are rare, occurring only near water or when provoked. Caimans crush prey with 1,000 pounds (454 kilograms) of jaw force, swallowing small items whole or tearing larger ones. Oversized prey is at risk of regurgitation or injury (Ross, 2018).

- Diet by Age: Juveniles (<3 feet / 0.9 meters) feed primarily on aquatic insects, small fish, amphibians, and crustaceans, relying on agility over strength. As they mature, adult caimans (>6 feet / 1.8 meters) transition to larger prey such as capybaras, birds, and aquatic reptiles, supported by their powerful jaws and enhanced predatory skills.

- Diet by Gender: Males and females consume similar food sources, but size-driven divergence occurs. Larger males often target vertebrate prey—including wading birds and turtles—especially during territorial displays, while gravid or nesting females favor consistent, smaller catches, such as fish and crabs, to minimize risk and conserve metabolic energy.

- Diet by Seasons: In the wet season (May–October), abundant fish and aquatic invertebrates dominate caiman diets due to flooded habitats. In contrast, during the dry season (November–April), receding waters concentrate prey into isolated pools, prompting caimans to scavenge or ambush trapped animals, including birds and carrion, maximizing foraging efficiency.

How Do Caiman Hunt Their Prey?

Caimans have hunting prowess, showcasing their skills as adept predators. Their hunting behavior is intriguing, emphasizing stealth and precision. Predominantly found in water environments, caimans display patience as they wait for the opportune moment to strike. Their hunting strategy involves using their robust jaws and sharp teeth to capture prey effectively. Moreover, their exceptional underwater vision helps them accurately target their victims.

These stealthy hunters navigate through the water silently, approaching their unsuspecting prey without detection. They make good use of their powerful tails to swiftly propel themselves towards their target, launching a sudden, surprising attack. Additionally, caimans possess a keen sense of smell, enabling them to locate prey even when hidden from view.

Upon successfully catching their prey, this animal employs their sharp teeth to secure and subdue them. Typically, the Caiman diet consists of fish, birds, and small mammals, which they consume by tearing them into manageable pieces. This hunting behavior exemplifies the intricate ecosystem where caimans play a crucial role as skilled predators.

Is Caiman Venomous?

Caimans aren’t venomous creatures; they rely on their physical strength and hunting skills to catch their prey. With powerful jaws and sharp teeth, caimans capture and hold their prey, then pull it underwater to eat. They don’t need venom to hunt.

Belonging to the non-venomous Alligatoridae family, which includes alligators and caimans, these reptiles stand out from venomous ones like snakes. Instead of relying on venom, caimans depend on their keen senses, stealthy movements, and physical abilities to thrive.

Despite their intimidating appearance, these fascinating creatures excel in their natural habitats through their natural hunting instincts and physical attributes.

When is Caiman Most Active During The Day?

Caimans are most active in the early morning and late afternoon, as they’re crepuscular animals —meaning they’re more active at dawn and dusk. During these times, they engage in hunting and feeding behaviors, using their sharp teeth and stealthy movements to catch prey.

In the hotter parts of the day, caimans bask in the sun or rest in the water to cool off, reducing their activity levels. This behavioral pattern aligns with their natural rhythms for hunting and regulating body temperature.

If you’re near caiman habitats in the morning or late afternoon, keep an eye out for these impressive creatures showcasing their hunting skills.

How Do Caimans Move on Land and Water?

Caimans are truly captivating creatures to observe for their fascinating movements on land and in water. On land, they demonstrate impressive agility, using their powerful muscles to crawl or slither across the terrain. Their robust limbs enable them to move swiftly over short distances.

When it comes to swimming, caimans excel. Using their powerful tails to propel themselves forward, they effortlessly glide through the water. Their streamlined bodies and webbed feet contribute to their graceful swimming abilities.

Watching a caiman navigate through different environments, whether on land or in water, showcases its movement skills. These creatures move with such efficiency and grace that it’s truly a sight to behold. So, take a moment to appreciate the natural beauty and impressive capabilities of caimans whenever you have the chance to witness them in action. “Observing caiman move on land and in water is a testament to their incredible adaptability and grace in their natural habitats.”

Do Caiman Live Alone Or In Groups?

Caimans are social creatures that typically live in groups, or congregations, in their natural habitats. These groups can vary in size depending on factors like food availability and habitat suitability. Living in groups offers caiman advantages such as increased protection from predators and more mating opportunities.

Group living enables caiman to communicate, share resources, and establish social hierarchies within their congregations. This social structure helps them navigate their environment effectively and thrive in the wild.

While caimans are social animals, they also exhibit solitary behaviors, particularly during nesting and breeding seasons.

Observing how caiman interact and manage their social dynamics within groups is fascinating. By living in congregations, these characteristics of reptiles demonstrate their adaptability and cooperation, underscoring the role of social connections in their survival strategies in the wild.

How Do Caiman Communicate With Each Other?

Living in groups allows caimans to develop effective communication strategies, which are crucial for their survival. Caimans use vocalizations, body language, and chemical signals to interact with one another. They emit low-frequency calls to announce their presence, attract mates, or warn others about dangers, which can travel efficiently through water, helping them stay connected even over long distances.

In addition to vocalizations, body language plays a significant role in caiman communication. Through body postures, tail movements, and eye contact, they express dominance, submission, or aggression within their group, enabling them to maintain social order and avoid conflict by accurately interpreting these signals.

Moreover, caimans rely on chemical signals to communicate effectively. By releasing pheromones into the water, they mark their territories, attract potential mates, and identify one another, aiding navigation and establishing their position within the group. These different communication methods are vital for their social interactions and survival in their habitat.

How Do Caiman Reproduce?

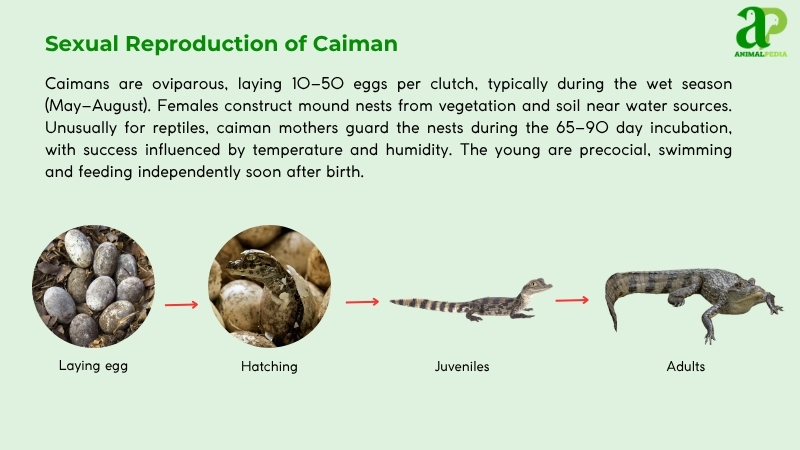

Caimans (genus Caiman) reproduce sexually via internal fertilization, ensuring offspring survival in Neotropical wetlands.

Breeding starts in the wet season (May–August). Males bellow and vibrate water to attract females, who respond with softer calls. Courtship involves nuzzling and synchronized swimming, culminating in mating in shallow waters. Both sexes may mate multiply.

Females lay 15–40 eggs in June–July, each weighing 0.15–0.2 pounds (70–90 grams). Eggs are placed in mound nests of mud and vegetation, which are guarded by females against predators such as coatis. Males depart post-mating. Flooding or drought can disrupt egg-laying, reducing clutch size, as seen in the Pantanal in 2017.

Eggs incubate for 65–80 days, hatching in August–October. Hatchlings, 8–10 inches (20–25 centimeters), stay near mothers for 6–12 months, eating insects and growing 1 foot (30 centimeters) yearly. They mature at 4–7 years.

Caimans live 30–40 years, with captives reaching 50. Their reproductive strategy supports wetland ecosystems, but habitat loss threatens breeding success (Magnusson & Campos, 2019).

How Long Do Caiman Live?

Caimans (genus Caiman) have a life span of 30–40 years in the wild, with captives reaching 50 years under controlled conditions. Lifespan varies slightly between different Caiman species but remains generally consistent across the Caimaninae subfamily. Their longevity contributes to the stability of wetland ecosystems, although habitat degradation poses risks.

Lifespan is consistent across sexes, averaging 35 years, with no notable differences between males and females. Juveniles face high predation from birds and larger caimans, reducing early survival rates, but adult caimans face fewer threats, enabling long-term survival in stable environments. Conservation efforts are essential to sustain populations and their ecological roles (Campos et al., 2020).

What Are The Threats Or Predators That Caiman Face Today?

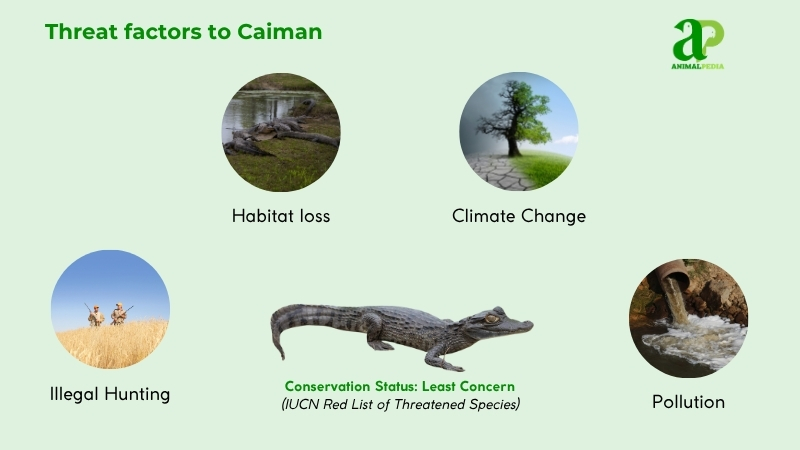

Caimans (genus Caiman) face habitat loss, pollution, illegal hunting, and climate change, threatening their survival in Neotropical wetlands. Predators primarily target juveniles, while human activities intensify these risks, necessitating conservation efforts.

- Habitat Loss: Deforestation and urbanization destroy 30% of Pantanal wetlands, reducing nesting and feeding sites, limiting population growth.

- Pollution: Agricultural runoff with pesticides impairs reproduction, with 10% of eggs showing developmental issues.

- Illegal Hunting: Poaching for skins and meat decreases populations, particularly Caiman yacare in Bolivia.

- Climate Change: Altered rainfall disrupts breeding cycles, reducing hatchling survival by 15% in flood-prone areas.

Caiman predators include jaguars, anacondas, and large birds (e.g., jabiru storks), preying on hatchlings (<2 feet/0.6 meters). Adults face few natural threats from opportunistic predators.

Human impacts are severe. Wetland drainage for agriculture and dam construction fragments habitats, and 40% of Amazonian wetlands have been degraded since 2000. Illegal trade persists despite CITES regulations, and urban expansion increases human-caiman conflicts, leading to culls. Research confirms these threats reduce population viability, urging habitat restoration (Escobedo-Galván et al., 2017).

Are Caiman Endangered?

Caimans (genus Caiman) are not endangered. Most species are classified as Least Concern by the IUCN, reflecting stable populations in Neotropical wetlands.

According to IUCN Threat Categories, Caiman crocodilus (spectacled caiman) and Caiman yacare (Yacare caiman) are Least Concern due to widespread distribution and adaptability. Caiman latirostris (broad-snouted caiman) is also Least Concern, though it faces localized threats. Melanosuchus niger (black caiman) is Conservation Dependent, recovering from past declines.

C.crocodilus populations exceed 1 million across Central and South America, with 500,000 in Brazil’s Pantanal alone. C. yacare numbers around 100,000–200,000 in Bolivia and Paraguay. M. niger has 25,000–50,000 individuals, rebounding due to conservation. C. latirostris maintains 100,000 across Argentina and Brazil.

Stable habitats and regulated hunting support caiman populations, but habitat loss and pollution pose risks to them. Conservation efforts, including CITES trade restrictions, ensure their persistence in wetlands such as the Amazon and the Pantanal (Magnusson & Campos, 2019).

What Conservation Efforts Are Underway?

Caimans have become a focus of targeted conservation efforts across Neotropical wetlands. These efforts are led by global and regional organizations such as Conservation International, the IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group, and the WWF. Since 2008, significant progress has been made in key areas, such as Colombia’s Curare-Los Ingleses Reserve, where the black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) population is recovering, with 123 individuals recorded in 2022 (Arellano, 2023).

Community-led monitoring in Colombia, supported by Conservation International, has emphasized habitat protection and population surveys. In Venezuela, the Orinoco caiman (Caiman crocodilus) has benefited from FUDECI’s long-standing head-start program, which has released more than 8,000 juveniles since 1983. These programs rely on hatchery-based release programs and aim to restore populations in areas impacted by habitat degradation and hunting.

Caimans are listed under CITES Appendix II, which regulates international trade and prohibits unlicensed export of caiman skins. In Brazil, the environmental agency IBAMA enforces strict rules for sustainable harvest. By 2019, it had approved 65 legal breeding facilities that meet conservation standards (Magnusson & Campos, 2019).

Brazil’s Caiman yacare ranching initiative produces over 80,000 skins annually through sustainable farming, balancing conservation and economic value. In Venezuela, approximately 200–300 Orinoco caimans are released annually from captive breeding programs. Colombia’s black caiman recovery efforts also show promising trends, thanks to dedicated fieldwork. In the U.S., Florida’s Croc Docs have removed 251 invasive caimans since 2013, aiding native crocodilian conservation.

Due to a 1996 hunting ban, the Caiman yacare population in the Pantanal has rebounded to an estimated 10 million by 2020—marking one of the most successful crocodilian recoveries to date.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do Caimans Make Good Pets?

No, caimans don’t make good pets. They need special care and can be dangerous. Consider other animals that are suitable for home environments. Research and choose a pet that better fits your lifestyle.

Can Caimans Live in Saltwater?

Yes, caimans can live in saltwater, but they also need access to freshwater. Saltwater can be harmful if not properly managed. Make sure their habitat meets their needs for a healthy life.

Are Caimans Dangerous to Humans?

Yes, caimans can be dangerous to humans, especially if provoked or cornered. Stay cautious around them, as they can behave aggressively when threatened. Avoid getting too close to caimans and respect their space for safety.

Do Caimans Hibernate During the Winter?

Yes, caimans may hibernate during the winter in warmer climates. Their hibernation period varies with temperature and food availability. Caimans slow down their metabolism and seek refuge in burrows or dense vegetation to survive the cold.

How Long Do Caimans Live in the Wild?

In the wild, caimans typically live for about 30 to 40 years. Caiman predators, environment, and food availability are factors impacting their lifespan. But hey, these creatures can impressively thrive and adapt, too!

Conclusion

To sum up, caimans are fascinating creatures with unique adaptations that help them thrive in their freshwater habitats. From their scaly skin to their powerful jaws, these stealthy predators play an essential role in the ecosystem. With conservation efforts in place, we can collaborate to safeguard these vulnerable species and guarantee their habitats are conserved for future generations to appreciate. So next time you spot a caiman, take a moment to admire the beauty and wonder of these incredible creatures!