Chameleons captivate with their color-shifting skin, independently rotating eyes, and prehensile tails. Nearly 200 species exist, ranging from 6 to 24 inches in length. Their distinctive morphology makes them unmistakable among reptiles.

Notable species include the veiled chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus) with its prominent casque, and the panther chameleon (Furcifer pardalis) renowned for its spectacular regional color variations. Panthers thrive across northern Madagascar, while veiled chameleons inhabit the Arabian Peninsula.

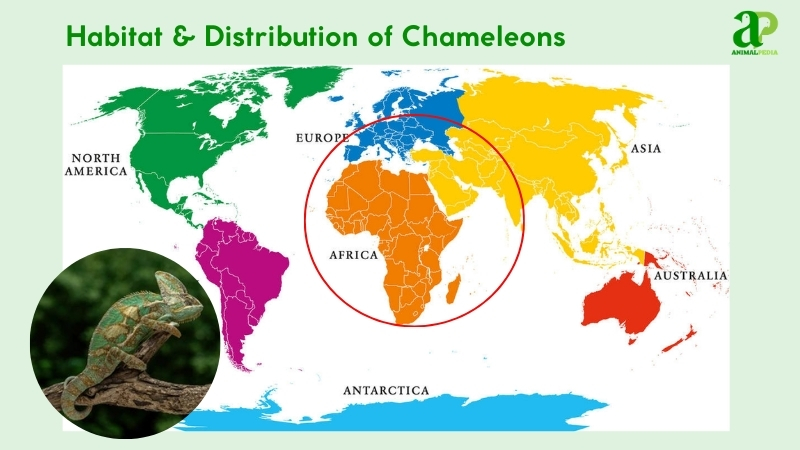

These remarkable reptiles populate sub-Saharan Africa, Madagascar, and parts of South Asia. They thrive in diverse ecosystems – from humid forests to savannas and mountainous terrain. Their famous chromatic adaptation serves multiple functions: camouflage, thermoregulation, and communication.

As specialized ambush predators, chameleons employ patience and precision. Their ballistic tongues – extending up to twice their body length – snare insects with astonishing accuracy. Their diet consists primarily of arthropods including crickets, grasshoppers, and beetles. Human interactions remain minimal in their natural habitat.

Reproductive cycles begin during the October-December mating season. Females deposit 20-80 eggs in shallow nests. Incubation periods vary from 5-10 months depending on environmental conditions and species. Hatchlings emerge at 3-5 cm, immediately capable of hunting. Sexual maturity occurs within 1-2 years, with wild specimens typically living 5-7 years.

This article explores chameleons’ distinctive anatomy, habitat requirements, and ecological significance, providing insight into these extraordinary lizards.

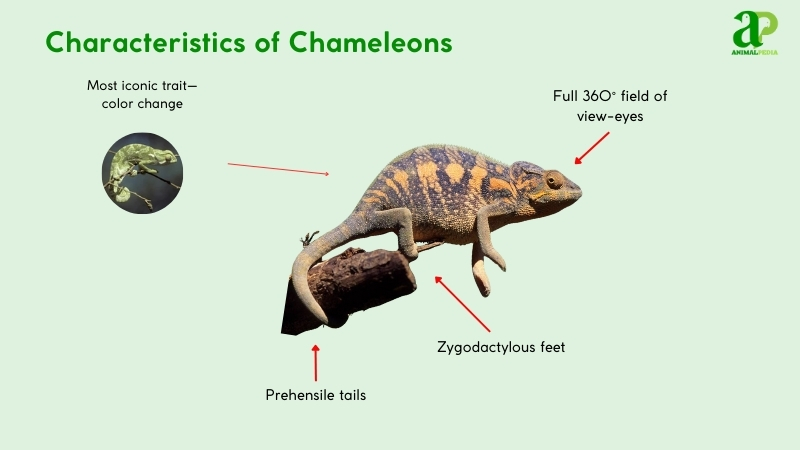

What Do The Chameleons Look Like?

Chameleons possess slim, tree-dwelling bodies measuring 15-60 cm (6-24 in). Their remarkable skin shifts between vibrant greens, reds, and blues, often displaying spotted or striped patterns. Rough, granular scales provide exceptional grip on branches.

Distinctive anatomical features include their zygodactylous feet (with toes grouped in opposable pairs) specialized for gripping branches, and a prehensile tail that functions as a fifth limb for balance and stability. Their independently moving eyes bulge outward like turrets, rotating 180° to scan for prey while maintaining a fixed body position—significantly outperforming the fixed gaze of related agamid lizards.

Chameleons possess an extraordinarily projectile tongue capable of extending to twice their body length. Their compressed body, short limbs with sharp claws, crested head with bony casques, and absent neck complete their specialized reptilian form.

Unlike geckos, chameleon chromatophores (specialized pigment cells) change color through hormonal control rather than direct neural stimulation. These color shifts primarily communicate mood and provide camouflage, a critical adaptation for survival in their native habitats, including Madagascar’s forests, as documented by Tolley and colleagues (2016).

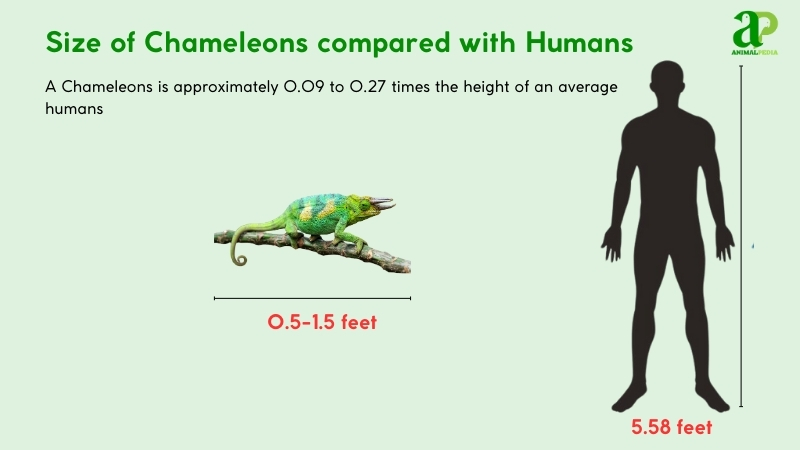

How Big Do Chameleons Get?

Chameleons typically measure 6–18 inches (15–45 cm) in length and weigh 0.1–0.4 lbs (50–200 g). Adult panther chameleons (Furcifer pardalis) often grow to 12–20 inches (30–50 cm) from snout to tail.

The largest species, Parson’s chameleon (Calumma parsonii), can reach 27 inches (68 cm) and weigh around 1.5 lbs (700 g). Native to Madagascar, it is among the heaviest lizards in its habitat (Tolley et al., 2016).

Males usually outsize females by 4–8 inches (10–20 cm) and 0.2–0.4 lbs (100–200 g), and tend to display more vibrant coloration in chameleon turning color behavior.

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 12–20 in (30–50 cm) | 8–16 in (20–40 cm) |

| Weight | 0.3–0.9 lbs (150–400 g) | 0.2–0.6 lbs (100–250 g) |

What Are The Unique Physical Characteristics Of The Chameleons?

Chameleons possess extraordinary adaptations that separate them from all other reptiles. Their most remarkable feature: independently rotating eyes that move in different directions simultaneously. This gives them a complete 360-degree vision field without turning their heads.

When hunting, these eyes work together—switching to binocular vision for precise depth perception. This allows chameleons to judge distance and strike with accuracy in dense forest canopies. Interestingly, their hunting style shows parallels with the stealth approach seen in arboreal lizards like the Flying Gecko, which also relies on camouflage and patience to ambush prey.

Zygodactylous feet (with toes fused into opposing groups) and prehensile tails function as grasping tools. These specialized appendages allow chameleons to navigate complex branch networks with exceptional stability and control.

Their famous color-changing ability relies on sophisticated iridophore cells containing guanine nanocrystals. As proven in Teyssier’s 2015 research, chameleons actively reorganize these crystals to reflect specific light wavelengths. This creates rapid transitions between greens, blues, reds, and yellows.

Contrary to popular belief, this color transformation serves multiple purposes beyond camouflage. Chameleons use chromatic shifts for thermoregulation (temperature control) and social communication—displaying dominance during territory disputes or attracting mates with vibrant patterns.

These unique physical traits create an unmistakable biological profile exclusive to the chameleon family, making them evolutionary specialists in their ecological niche.

How Do Chameleons Sense Their Environment With Its Unique Features?

Chameleons sense their environment through remarkable adaptations. Color-changing skin serves dual purposes: camouflage and communication. This transformation occurs through specialized cells called chromatophores that expand or contract to reflect different wavelengths (Anderson, 2016).

Their independently rotating eyes provide near-complete visual awareness, scanning surroundings without head movement. This panoramic vision helps detect both predators and potential meals simultaneously, a crucial survival advantage in their natural habitats, from dense jungles to open grasslands.

The chameleon’s ballistic tongue extends at extraordinary speeds—up to twice their body length in milliseconds. This precision hunting tool uses specialized muscle tissue and a unique hydrostatic skeleton for rapid prey capture. Their vibrational sensitivity complements vision, allowing them to perceive subtle movements through branches.

A prehensile tail functions as a fifth limb, gripping branches securely while navigating arboreal environments. This appendage provides stability and balance, essential for a creature that moves deliberately through three-dimensional space (Teyssier et al., 2015).

Anatomy

Chameleons possess highly specialized internal systems that reflect their adaptation to life in trees. These systems enable them to hunt efficiently, conserve resources, and respond rapidly to environmental stimuli.

- Respiratory System: Chameleons breathe through lungs equipped with air sacs, improving oxygen exchange—vital for active movement in humid forests (Perry, 2019).

- Circulatory System: Their three-chambered heart supports vigorous activity and powers skin pigment changes for camouflage (Tolley & Herrel, 2014).

- Digestive System: A short but efficient gut breaks down protein-rich insect diets, fueling high-energy hunting (Anderson, 2016).

- Excretory System: Their kidneys excrete uric acid instead of urea, minimizing water loss—an essential trait in dry habitats (Dzialowski, 2016).

- Nervous System: A complex nervous system enables precise control over turret-like eyes and ballistic tongue strikes (Lustig et al., 2017).

Together, these physiological adaptations allow chameleons to maintain metabolic efficiency and avoid predators. These internal systems are as vital to survival as their external traits, ensuring success in both rainforest canopies and drier savannas.

See more: Mediterranean House Gecko

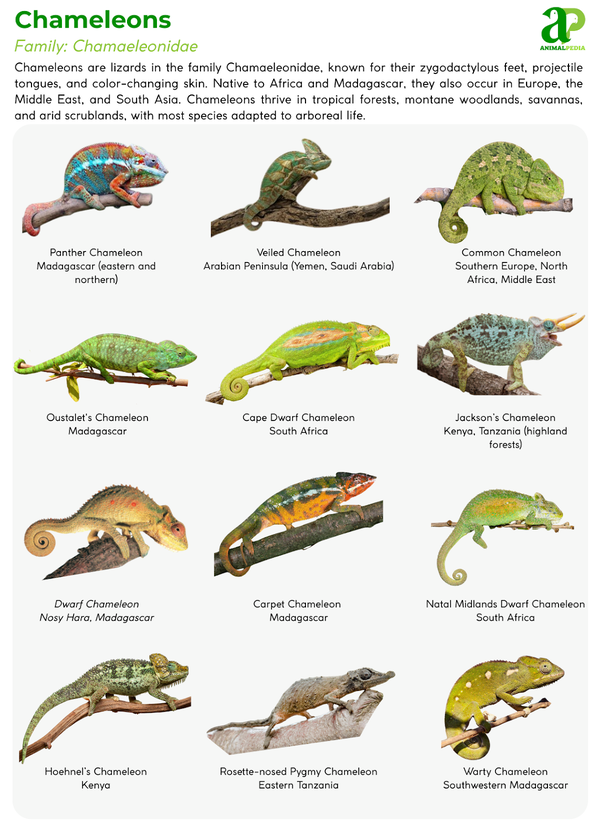

How Many Types Of Chameleons?

Approximately 200 chameleon species exist, showcasing remarkable biodiversity within the Chamaeleonidae family. Classification relies on the Linnaean system, developed by Carl Linnaeus, emphasizing morphological and genetic traits (Tolley & Herrel, 2014). Phylogenetic analysis further refines taxonomy, integrating molecular data for precision.

The branch diagram traces families (Chamaeleonidae), genera (e.g., Chamaeleo, Furcifer), and species (e.g., Chamaeleo calyptratus). It illustrates evolutionary divergence across arboreal and terrestrial lineages. Special cases in Squamata order classification include dwarf chameleons (Brookesia), with unique miniaturization, and atypical ground-dwelling species like Chamaeleo namaquensis, adapted to arid deserts (Glaw, 2015).

Chamaeleonidae

├── Genus: Chamaeleo

│ └── Species: C. calyptratus

├── Genus: Furcifer

│ └── Species: F. pardalis

├── Genus: Brookesia

│ └── Species: B. minima

These distinctions highlight chameleons’ adaptive radiation, driven by ecological niches and genetic variation, shaping their global distribution.

Where Do Chameleons Live?

Chameleons inhabit Africa, Madagascar, southern Europe, and parts of Asia. Half of all species live in Madagascar’s rainforests and highlands. Endemic populations thrive in specific habitats: Furcifer pardalis occupies Madagascar’s eastern rainforests, while Bradypodion pumilum dwells in South Africa’s coastal forests.

These arboreal reptiles require humid environments with dense vegetation. Such habitats provide perfect conditions for their specialized adaptations: camouflage capabilities, hunting strategies, and thermoregulation needs. Warm climates and insect abundance support their metabolic requirements and insectivorous diet.

Paleontological evidence shows chameleons have occupied these regions for over 60 million years. Their limited geographic distribution stems from highly specialized evolutionary adaptations. Research by Tolley and colleagues (2016) presents phylogenetic data connecting chameleon distribution patterns to continental drift and climate stability in their native ranges.

How Do Seasonal Changes Affect Their Behavior?

Chameleons exhibit seasonal behavioral shifts in response to climate patterns common in their native tropical regions. These changes are tightly linked to ecological resource availability.

- Wet Season: Increased rainfall boosts insect prey, prompting active hunting and vibrant color displays for mating. Chameleons expand territories to secure partners.

- Dry Season: Reduced food and water lead to energy conservation. Chameleons minimize movement, adopt duller hues for camouflage, and seek shaded microhabitats to avoid desiccation.

These cyclical behavioral adaptations align with environmental pressures, optimizing chameleon survival and reproduction across variable ecosystems in Madagascar, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Asia.

What Is The Behavior Of Chameleons?

Chameleons display highly specialized behaviors that reflect their evolutionary adaptation to life in trees. Their actions are guided by survival, reproduction, and environmental interaction.

- Feeding Habits: Chameleons hunt insects using rapid, projectile tongues. Precision and camouflage ensure efficient prey capture (Anderson, 2016).

- Bite & Venomous: Chameleons lack venom and rarely bite. Defensive bites are weak, posing no threat (Tolley & Herrel, 2014).

- Daily Routines and Movements: They are diurnal, basking mornings for thermoregulation. Slow movements conserve energy in foliage.

- Locomotion: Arboreal climbing uses prehensile tails and zygodactylous feet. Deliberate steps enhance stability (Higham et al., 2015).

- Social Structures: Mostly solitary, males compete for territory. Females signal receptivity during mating season.

- Communication: Color changes and body postures convey mood and intent. Visual signals dominate interactions.

These behavioral patterns ensure chameleons remain effective predators and adaptable survivors in complex environments.

What Do Chameleons Eat?

Chameleons are carnivores, primarily consuming insects like crickets and locusts, with larger species occasionally eating small birds or lizards. They capture food using rapid tongue projection, swallowing prey whole. If prey is too large, it is typically avoided to prevent injury or choking (Anderson et al., 2016). Despite their carnivorous nature, they pose no threat to humans.

- Diet by Age

Chameleons are insectivores from hatching to adulthood. Juveniles feed on small insects such as fruit flies (Drosophila) and pinhead crickets to match their limited gape size. As they mature, their diet expands to include larger prey like locusts, beetles, and even small lizards in larger species (Furcifer oustaleti).

- Diet by Gender

There is no strong sexual dimorphism in diet. Both males and females consume similar prey types. However, dominant males in territorial species may access more prey due to a greater range and a competitive advantage. Females may temporarily reduce feeding during gravidity (egg development).

- Diet by Seasons

Seasonal shifts influence feeding behavior. During the wet season (November–April), insect populations increase, leading to higher hunting frequency and food intake. In the dry season (May–October), chameleons reduce activity, adopt energy-conserving behaviors, and consume less, focusing on slow-moving or easily accessible prey.

How Do Chameleons Hunt Their Prey?

Chameleons hunt with deadly precision. Their independent eye movement gives them a 360-degree field of vision to track prey without moving their heads. Each eye can rotate and focus separately, creating a unique form of binocular vision when targeting prey.

When a chameleon spots an insect, it locks both eyes forward. The ballistic tongue becomes their primary weapon. This specialized organ can extend up to twice its body length and accelerate from 0 to 60 mph in a hundredth of a second—faster than a sports car.

The hyoid apparatus, a specialized bone structure, powers this remarkable tongue projection. The chameleon’s tongue tip contains a sticky mucus coating combined with muscle contractions that create suction, ensuring prey attachment. This projectile feeding mechanism allows chameleons to capture prey from a safe distance.

Most prey consists of arthropods like flies, crickets, and moths. The entire strike sequence—from targeting to capture—typically occurs in less than 0.07 seconds, making it one of nature’s most efficient predatory adaptations.

Are Chameleons Venomous?

Chameleons are reptiles, but unlike some of their scaled relatives, they lack venomous glands. Instead of toxins, these remarkable lizards rely on their extraordinary hunting adaptations – lightning-fast tongues and masterful camouflage abilities. Their binocular vision allows precise prey detection, while specialized zygodactylous feet and prehensile tails enable them to navigate their arboreal habitats with surgical precision.

When hunting insects and small invertebrates, chameleons deploy their ballistic tongues – a biological projectile that can extend to twice their body length in milliseconds. This unique predatory mechanism demonstrates their evolutionary specialization as ambush hunters. Their success in capturing prey stems from patience, accuracy, and these distinctive anatomical features rather than any toxic compounds.

When Are Chameleons Most Active During The Day?

Chameleons are most active in the early morning and late afternoon when temperatures are milder, allowing them to search for food and interact with others. As the day heats up, chameleons tend to slow down and find shelter to prevent overheating.

However, certain species like the Jackson’s chameleon may still be active in the hot periods, especially if there are opportunities for hydration and foraging. Observing chameleons during their peak activity times offers a fascinating glimpse into their natural behaviors and movements in their environments.

If you want to see these color-changing creatures in action, aim to observe them during these active periods!

How Do Chameleons Move On Land And Water?

Chameleons move in fascinating ways both on land and in water. When on land, these creatures move slowly and carefully, almost as if they’re enjoying each step. Their feet have a strong grip that helps them traverse challenging terrain effortlessly, holding onto branches or rocks with precision. As they walk, chameleons have a distinctive swaying motion that adds to their graceful and captivating nature.

Surprisingly, chameleons are skilled swimmers in water. Using their long tails for propulsion, they move smoothly through the water with a sinuous body motion. Watching these reptiles glide beneath the water’s surface is truly mesmerizing, especially as they blend in with their aquatic surroundings.

Whether on land or in water, chameleons exhibit a sense of freedom and agility that’s truly enchanting to observe. Their unique way of moving complements their elusive and mysterious characteristics, making them even more intriguing to study and appreciate.

Do Chameleons Live Alone Or In Groups?

Chameleons are solitary creatures. They roam their territories alone, hunting insects and finding shelter without companions. This independent behavior is hardwired into their nature as specialized reptiles adapted for individual survival.

During breeding season, adult chameleons briefly interact. Males seek females, mate, and then separate immediately. The female later deposits eggs and leaves them to develop without parental care, maintaining their solitary lifestyle.

Territorial behavior defines chameleon social structure. Males establish and defend specific areas, using color displays and physical posturing to ward off rivals. This spatial separation prevents competition for resources like hunting grounds, basking spots, and potential mates.

Juvenile chameleons disperse shortly after hatching, instinctively avoiding competition with siblings. This early independence reinforces their solitary nature throughout their lifecycle, from hatchling to mature adult.

The solitary existence of chameleons contrasts with many other reptile species. This isolation strategy allows each individual to utilize their unique adaptations—color-changing camouflage, specialized vision, and prehensile tails—without the complications of group dynamics.

How Do Chameleons Communicate With Each Other?

Chameleons communicate through a silent yet complex language of visual signals. These solitary reptiles rarely touch but have evolved sophisticated non-verbal communication methods. Their most remarkable skill is chromatic signaling – changing skin colors and patterns to express mood, territorial claims, or reproductive readiness.

Body language forms the core of chameleon communication. When threatened, these reptiles employ defensive displays by expanding their bodies, hissing audibly, or gaping their mouths wide. These behaviors establish clear boundaries without physical confrontation, essential for their primarily solitary lifestyle in the wild.

Chameleons use postural communication through deliberate movements. Males may perform head-bobbing displays to signal dominance, while slow swaying often indicates submission. Females signal receptivity or rejection to potential mates through specific color patterns and body positions. Through these visual semantics, chameleons effectively navigate their social interactions despite their preference for solitude.

How Do Chameleons Reproduce?

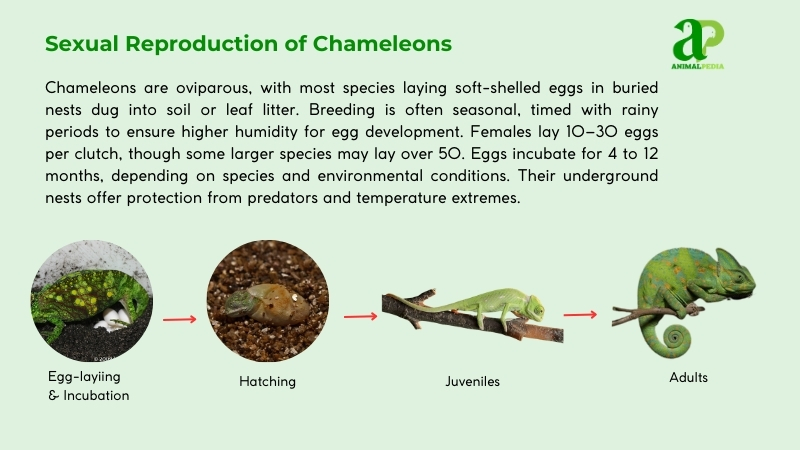

Chameleons reproduce oviparously, with most species laying eggs. Breeding occurs during the wet season (November–April), when males display vibrant colors and head-bobbing to attract females (Karsten et al., 2015). Females signal receptivity through subdued hues. Courtship involves visual displays, with males approaching cautiously to avoid aggression.

Post-mating, females lay 20–50 eggs, each weighing approximately 0.5–1 gram, buried in moist soil. Nests lack active protection; females conceal them to deter predators. Stress or malnutrition can interrupt egg-laying, often during drought (Glaw, 2015). Males and females part post-mating, resuming solitary lives.

Eggs incubate for 4–12 months, depending on species and temperature. Hatchlings emerge independent, feeding on small insects and growing rapidly. Chameleons reach maturity in 1–2 years. Chameleon life expectancy is around 2–5 years, with some species living longer in captivity. Conservation threats, like habitat loss, impact reproductive success.

How Long Do Chameleons Live?

Chameleons survive 2-5 years in natural habitats, while certain species reach up to 7 years under proper captive care. Their life cycle progresses through distinct phases: egg incubation (4-12 months), juvenile development (1-2 years), and adult maturity.

Male and female chameleons generally share similar longevity, though females often experience shorter lives due to reproductive strain (Glaw, 2015). Diminutive species like Brookesia typically have abbreviated lifespans of merely 1-2 years.

Several factors impact chameleon longevity, including predation, environmental degradation, and habitat destruction. In captivity, these remarkable reptiles may enjoy extended lives thanks to consistent nutrition, regulated temperatures, and veterinary care – though improper husbandry can introduce stress that significantly reduces their lifespan potential.

What Are The Threats Or Predators That Chameleons Face Today?

Chameleons face diverse threats in their natural habitats, with both environmental pressures and human activities endangering populations across their natural habitat.

- Habitat Loss: Deforestation due to logging, agriculture, and urban development reduces critical arboreal habitats. Species with small ranges, such as Furcifer campani, are particularly vulnerable (Jenkins et al., 2014).

- Illegal Wildlife Trade: Many chameleon species are trafficked for the exotic pet market, often leading to population declines. Poor handling and high mortality during transit further stress wild populations (Carpenter et al., 2015).

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures and altered precipitation disrupt breeding cycles and reduce insect prey availability, especially in montane ecosystems (Herrel & Tolley, 2018).

- Invasive Species: Predators like domestic cats and rats introduced by humans pose serious threats, especially on islands where chameleons evolved without such predators.

Collectively, these threats place substantial pressure on chameleon populations, especially species with limited ranges or specialized habitat needs.

Are Chameleons Endangered?

What Conservation Efforts Are Underway?

Chameleon conservation faces two major threats: habitat destruction and illegal wildlife trade. Since 2016, the Archipelagos Institute has protected Mediterranean chameleons on Samos, Greece through habitat restoration and local protection zones. In Madagascar, home to the highest chameleon diversity, Caméléon Center Conservation has gathered vital ecological data since 2013 to combat deforestation threatening endemic species.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) has regulated chameleon commerce since 1975. Most chameleon species, including veiled chameleons and panther chameleons, appear on CITES Appendix II, which permits captive breeding with proper permits but prohibits wild collection. This framework blocks illegal trafficking while preserving wild populations.

Ex-situ conservation programs led by zoos and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) maintain genetic diversity for threatened species. AZA’s Species Survival Plans have successfully increased populations of critically endangered chameleons since 2018. A notable success story is Chapman’s pygmy chameleon, with 38 individuals reintroduced to natural habitats in Malawi by 2016. The South African National Biodiversity Institute confirmed the species’ continued survival in 2021 after fears of extinction.

Conservation organizations including World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation promote habitat protection and sustainable practices across chameleon ranges. These coordinated efforts have stabilized populations for 38% of threatened chameleon species according to IUCN Red List assessments.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Chameleons Change Their Color To Match Any Background?

Yes, chameleons can change their color to match many backgrounds. They adjust their hues through specialized cells called chromatophores. This transformation helps them blend in with their surroundings, serving as a form of camouflage in various environments.

Are There Any Chameleons That Live In Colder Climates?

Yes, some chameleons can thrive in colder climates. These adaptive reptiles possess unique characteristics that enable them to survive in diverse environments. Their ability to regulate body temperature and behaviors help them navigate and flourish in colder regions.

Do Chameleons Make Any Sounds Or Vocalizations?

Chameleons do not make sounds or vocalizations. They communicate mainly through visual cues and body language. So, if you’re wondering about chameleon noises, don’t expect to hear any – they’re silent creatures.

Are Chameleons Social Animals Or Do They Prefer Solitude?

Chameleons value solitude; they are not social creatures. Embrace your alone time like these fascinating reptiles do. Enjoy your freedom and time spent in solitude like a chameleon in its habitat.

Do Chameleons Have Any Specific Dietary Preferences Or Restrictions?

You should feed chameleons a diet rich in insects like crickets, mealworms, and waxworms. Make sure to provide a variety of gut-loaded insects. Avoid feeding them toxic insects like fireflies, as they can harm the chameleons.

Conclusion

Chameleons stand as evolutionary marvels with their color-changing abilities, prehensile tails, and independently rotating eyes. From tropical forests to arid deserts, these specialized reptiles have adapted to diverse ecosystems across Africa, Madagascar, southern Europe, and parts of Asia. Their remarkable camouflage techniques serve not just for hiding, but also for thermoregulation and communication with other chameleons. The ballistic tongue projection system sets them apart in the animal kingdom, allowing precise capture of prey at distances up to twice their body length. Conservation efforts remain vital as habitat loss threatens many of the 160+ chameleon species. Next time you encounter these master ambush predators, observe their deliberate movements and appreciate the evolutionary refinements that make them true icons of adaptation.