Flying geckos (Ptychozoon genus) include 13 species with gliding adaptations. Ptychozoon kuhli (Kuhl’s parachute gecko) and Ptychozoon trinotaterra (Cambodian parachute gecko) are notable specimens. These arboreal reptiles measure 4–8 inches (10–20 centimeters) and possess distinctive patagia (skin flaps) along their flanks, interdigital webbing, and flattened tails that enable controlled aerial descents up to 197 feet (60 meters). Their cryptic patterning—brown, black, and tan blotches—provides effective camouflage in Southeast Asian forest ecosystems. Distributed across the Indomalayan realm, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Nicobar Islands, their microscopic setae on toe pads create van der Waals forces for adhesion to diverse surfaces.

These specialized lizards inhabit tropical rainforest biomes, primarily in lowland and coastal forests of Southeast Asia. P. kuhli thrives in the dipterocarp forests of Malaysia and Indonesia, while P. Horsfieldi occupies higher canopy strata. They readily adapt to anthropogenic structures, utilizing crevices and roofs as microhabitats. Dense vegetation and high relative humidity are essential to their arboreal lifestyle, supporting both nocturnal foraging and gliding.

Flying geckos are nocturnal insectivorous mesopredators that employ sit-and-wait predation tactics. They stalk arthropods like crickets, moths, and beetles, relying on stealth and disruptive coloration. Their specialized diet focuses on small invertebrates, with minimal human interaction beyond occasional collection for the exotic pet trade. Their parachuting capability serves dual purposes: predator avoidance and efficient canopy navigation, enhancing their hunting success in three-dimensional forest environments.

Reproductive biology centers on seasonal mating during monsoon periods (March–May). Females deposit two calcified eggs in communal nests, typically in tree hollows or building structures. Embryonic development spans 60–90 days, with hatchlings showing precocial behavior, hunting independently upon emergence. Sexual maturity occurs at 6–8 months, and longevity averages 5–8 years in captivity, though it is generally shorter in natural settings due to predation pressure.

This overview examines flying geckos’ unique morphological adaptations, ecological niche specialization, and behavioral strategies. Their sophisticated gliding mechanisms, habitat preferences, and reproductive patterns provide insights into their evolutionary success in tropical forest ecosystems.

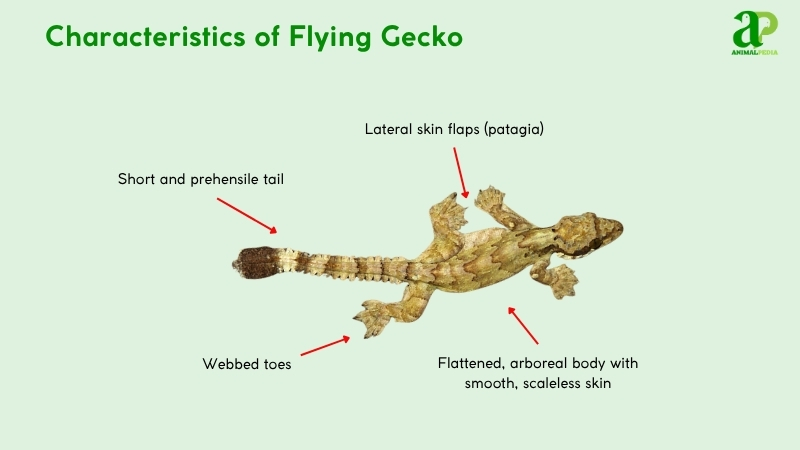

What do the Flying Geckos look like?

Flying geckos (genus Ptychozoon) have distinctive flattened bodies built for tree life. Their skin shows cryptic patterns of brown, tan, and black blotches that match tree bark perfectly. Their most notable feature: lateral skin flaps called patagia and webbed toes that enable gliding. These geckos possess broad heads with large, lidless eyes and vertical pupils for night vision. Short, prehensile tails help with balance, while microscopic toe setae let them stick to nearly any surface.

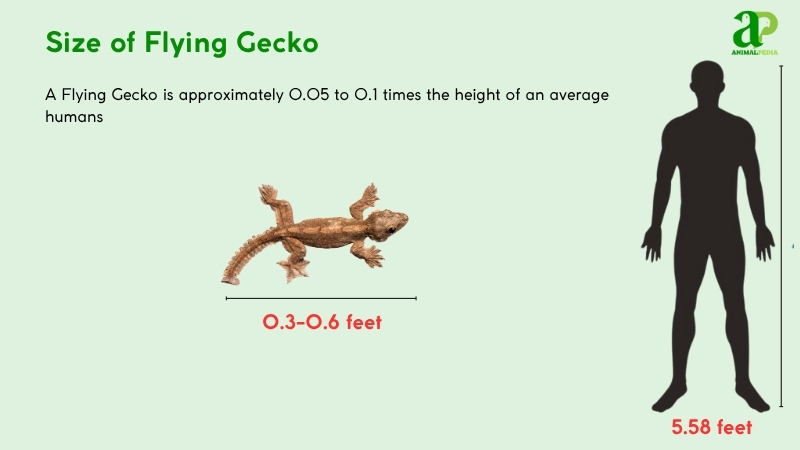

How big do Flying Geckos get?

Flying geckos average 4–8 inches (10–20 centimeters) in length, snout to tail, and weigh 0.5–1.5 ounces (15–40 grams). These measurements, consistent across species like Ptychozoon kuhli, reflect their lightweight, arboreal build suited for gliding.

The largest recorded specimen, a Ptychozoon kuhli from Borneo, reached 8.3 inches (21 centimeters) and 1.8 ounces (50 grams), documented in a 2019 study from Malaysia’s rainforest canopy.

Males and females show minimal size differences, with males slightly longer by 0.2–0.4 inches (0.5–1 centimeter). Females may weigh marginally more due to egg-carrying. Below is a table summarizing key distinctions.

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 4.2–8.3 in (10.5–21 cm) | 4.0–8.0 in (10–20 cm) |

| Weight | 0.5–1.7 oz (15–48 g) | 0.6–1.8 oz (17–50 g) |

What are the unique physical characteristics of the Flying Geckos?

Flying geckos possess lateral skin flaps called patagia, a unique trait in the gecko family. These membranous extensions stretch from the neck to the hind limbs, enabling glides up to 197 feet. Their webbed toes and flattened, serrated tails provide exceptional aerodynamic control during flight. The cryptic coloration—mottled brown, tan, and black—helps them blend with tree bark, offering specialized camouflage unlike most other geckos.

How do Flying Geckos adapt with their unique features?

Flying geckos survive in Southeast Asian rainforests through key adaptations. Their patagia (wing-like membranes), webbed digits, and serrated tails enable glides up to 197 feet, helping them evade predators and access food across dense canopies. Their cryptic coloration blends with tree bark, reducing detection risk.

Large, lidless eyes with vertical pupils enhance nocturnal vision, critical for hunting in darkness. Microscopic setae on their toes create molecular adhesion, allowing movement across varied surfaces. Acute auditory perception detects predator movements, while sensitive olfactory systems locate insect prey. These evolutionary traits in species like Ptychozoon kuhli perfectly suit their arboreal existence.

Anatomy

Flying geckos exhibit a suite of physiological systems finely tuned to their arboreal, nocturnal lifestyle in Southeast Asian rainforests. Their internal anatomy supports their agility, gliding ability, and high-energy behavior in humid, forested environments.

- Respiratory System: Flying geckos breathe through lungs with thin-walled air sacs, optimized for oxygen exchange in humid rainforests. Efficient respiration supports their active gliding lifestyle.

- Circulatory System: A three-chambered heart pumps blood, delivering oxygen to muscles during glides. Closed circulation ensures rapid response in their arboreal environment.

- Digestive System: A short digestive tract processes insect prey, with a stomach and intestines extracting nutrients quickly, suited for their high-metabolism nocturnal foraging.

- Excretory System: Kidneys filter waste, excreting uric acid to conserve water. This adaptation aids survival in tropical canopies with limited water access.

- Nervous System: A well-developed brain and optic nerves enhance nocturnal vision and coordination, critical for gliding and predator evasion in dense forests.

Together, these integrated systems illustrate how evolution has shaped flying geckos for survival above ground. Each physiological trait contributes to their agility, camouflage, and efficiency in navigating the complex vertical world of tropical forest canopies.

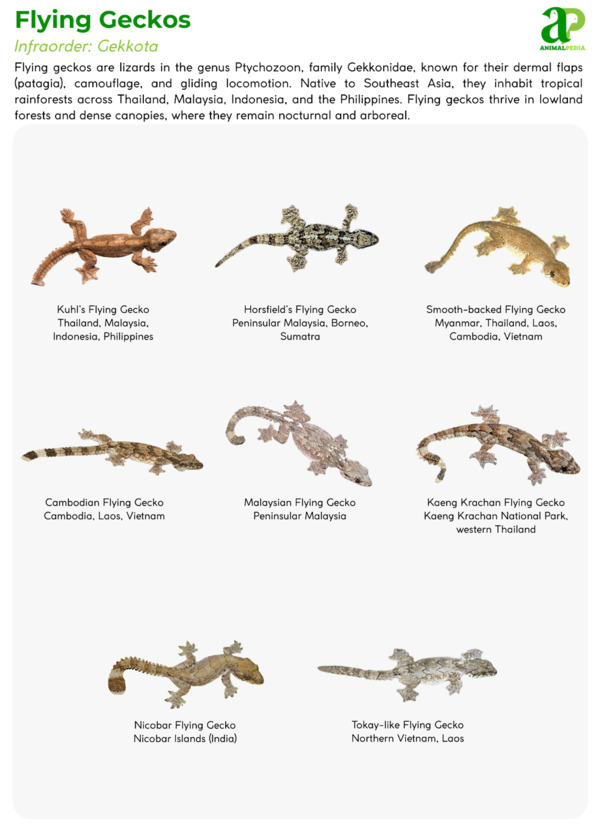

How many types of Flying Geckos?

Flying geckos, genus Ptychozoon, comprise 13 recognized species within the Gekkonidae family. Key species include Ptychozoon kuhli (Kuhl’s parachute gecko) and Ptychozoon trinotaterra (Cambodian parachute gecko), identified in Southeast Asia.

Classification is based on morphological and genetic traits, established by herpetologists like Bauer and Gamble through phylogenetic analysis. Their work integrates anatomical features like patagia and molecular data to delineate species.

The branch diagram traces Gekkonidae (family) to Ptychozoon (genus), splitting into species like kuhli, lionotum, and trinotaterra.

Order: Squamata

└── Family: Gekkonidae

└── Genus: Ptychozoon

├── Species: Ptychozoon kuhli – Kuhl’s Flying Gecko

├── Ptychozoon horsfieldii – Horsfield’s Flying Gecko

├── Ptychozoon lionotum – Smooth-backed Flying Gecko

├── Ptychozoon trinotaterra – Three-spotted Flying Gecko

├── Ptychozoon cicakterbang – Malaysian Flying Gecko

├── Ptychozoon kaengkrachanense – Kaeng Krachan Flying Gecko

├── Ptychozoon intermedium – Intermediate Flying Gecko

├── Ptychozoon nicobarense – Nicobar Flying Gecko

└── Ptychozoon tokehos – Tokay-like Flying Gecko

Special cases include Ptychozoon horsfieldi, noted for broader patagia, and Ptychozoon rhacophorus, with distinct tail serrations, reflecting adaptive divergence in rainforest canopies. These classifications, grounded in recent studies, highlight the genus’s evolutionary diversity.

Where do Flying Geckos live?

Flying geckos inhabit the lush rainforests of Southeast Asia, primarily in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Nicobar Islands. The species Ptychozoon kuhli dominates Borneo and Sumatra, while Ptychozoon trinotaterra occupies Cambodia’s lowland forests. These tropical habitats feature dense canopies and high humidity levels, perfectly suited for their arboreal lifestyle and gliding capabilities.

How do seasonal changes affect their behavior?

Flying geckos, particularly Ptychozoon kuhli, display distinct seasonal behaviors shaped by the climatic rhythms of Southeast Asia. These arboreal reptiles adapt their activity patterns, foraging strategies, and reproductive cycles in response to shifting environmental cues.

- Wet Season (March–October): Increased humidity boosts nocturnal hunting, with geckos gliding to pursue abundant insects. Mating peaks, and females lay eggs in communal nests.

- Dry Season (November–February): Reduced prey availability limits foraging. Geckos conserve energy, minimizing gliding and retreating to tree crevices or human structures for shelter.

These seasonal shifts illustrate the gecko’s ecological flexibility, enhancing survival in dynamic rainforest ecosystems. Their behavior reflects a fine-tuned response to resource availability and climatic stress, supporting both energy efficiency and reproductive success.

What is the behavior of Flying Geckos?

Flying geckos are highly adapted arboreal reptiles native to Southeast Asian rainforests. Their behaviors reflect fine-tuned ecological specialization for canopy life, especially under nocturnal conditions where visibility is low and movement must be precise. Each behavioral trait contributes to their survival in complex vertical environments.

- Feeding Habits: Nocturnal insectivores, they ambush small insects like crickets. Camouflage aids their stealthy hunting.

- Bite & Venomous: Non-venomous; their bite is harmless. They rarely bite, preferring flight over fight.

- Daily Routines and Movements: Active at night, they glide between trees. Daytime is spent hidden in crevices.

- Locomotion: Gliding via patagia allows 197-foot (60-meter) leaps. Adhesive toe pads ensure precise landings.

- Social Structures: Solitary, they interact only during mating. Territorial males may display aggression.

- Communication: Vocalizations include soft chirps for mating. Body postures signal territory claims.

Together, these behaviors illustrate an elegant survival strategy. From silent glides to cryptic camouflage, flying geckos master their niche through behavioral precision—each action fine-tuned to life among the treetops.

What do Flying Geckos eat?

Flying geckos are strict insectivores, favoring small insects like crickets, moths, and beetles. They do not attack humans, as their non-venomous bite is reserved for prey. All rely on nocturnal ambush tactics, using camouflage and gliding to capture prey. They swallow prey whole, aided by a short digestive tract. Larger prey is avoided, preventing choking or digestive issues.

- Diet by Age

Juvenile Flying Geckos feed on tiny insects like fruit flies, springtails, and termite workers. Their small body size limits prey choices, but rapid growth demands high protein intake. As they mature, Flying Geckos’ diet expands to include larger prey such as moths, beetles, and spiders. Adults rely on high-energy insect prey to fuel gliding and territorial behavior.

- Diet by Gender

Both male and female Flying Geckos are insectivorous and show no significant difference in dietary preferences. Males may defend light-rich or prey-dense areas, gaining access to more consistent food sources. However, no evidence suggests sex-based divergence in prey selection or nutritional requirements across the genus Ptychozoon.

- Diet by Seasons

Seasonal rainfall patterns shape feeding strategies. In the wet season, insect activity peaks, and geckos hunt more frequently, often using gliding to ambush prey. During the dry season, lower prey density leads to more energy-conserving behaviors. Geckos reduce gliding, forage closer to shelter, and may rely on slower-moving arthropods to maintain caloric intake.

How do Flying Geckos hunt their prey?

Flying Geckos hunt with stealth and precision. They patrol tree branches looking for insects, relying on their exceptional night vision to detect prey movement.

When hunting, these lizards are motionless, waiting for prey to come within striking distance. They ambush insects, spiders, and small vertebrates by lunging forward with speed. Their adhesive toe pads ensure stable positioning during attacks.

Flying Geckos use their specialized jaws to capture prey with a swift bite. Unlike some predators, they don’t track prey over long distances but instead employ a sit-and-wait strategy. Their camouflaged bodies blend perfectly with tree bark, making them nearly invisible to both prey and predators.

The gecko’s hunting technique proves highly effective in their rainforest habitat. They primarily feed at dusk and dawn when insects are most active. Their gliding membranes sometimes aid hunting by allowing them to pursue prey across gaps between trees without descending to the forest floor.

For a daytime counterpart with bold colors and active hunting, see the Day gecko.

Are Flying Geckos venomous?

Flying Geckos don’t possess venom, making them safe and fascinating creatures to observe. Instead of relying on venom, these agile geckos use their speed and agility to catch prey. Their hunting technique involves launching themselves into the air with their strong legs and tail, gliding effortlessly from tree to tree in search of insects.

These geckos are non-threatening to humans and other animals as they lack venom glands. This allows for peaceful observation and interaction without any risk of venom-related harm.

Enjoy their graceful movements and beauty up close, knowing that they pose no danger in terms of venom.

When are Flying Geckos most active during the day?

Flying Geckos exhibit crepuscular behavior, reaching peak activity during early morning hours and late afternoon periods. These arboreal reptiles thermoregulate by basking in the morning sunlight to raise their body temperature, then become increasingly active again as twilight approaches. During these optimal activity windows, they engage in predatory hunting, intraspecific social interactions, and demonstrate their gliding capabilities.

How do Flying Geckos move on land and water?

Flying Geckos display agility both on land and in water. On land, these creatures can move swiftly and nimbly, using their strong limbs and specialized toe pads to grip onto surfaces and maneuver through their environment with ease.

In water, Flying Geckos showcase surprising swimming skills. Their flattened bodies and long tails allow them to swim gracefully and efficiently, demonstrating their adaptability in different settings. Whether gliding through the air, scurrying on the ground, or swimming in water, Flying Geckos exhibit a sense of freedom and fluidity in their movements that captivates observers.

Their ability to navigate through diverse terrains highlights their impressive versatility and prowess as adaptable animals. Watching Flying Geckos in action on land and in water is truly mesmerizing, showcasing the unique ways in which they interact with their surroundings.

Do Flying Geckos live alone or in groups?

Flying Geckos live solitary lives, not in groups or colonies. These arboreal reptiles (Ptychozoon species) maintain individual territories in their natural rainforest habitats.

Adult Flying Geckos avoid each other except during breeding season. Each gecko establishes its own territory where it hunts and shelters independently. This solitary behavior helps reduce competition for limited food resources like insects and small invertebrates.

During mating periods, males will temporarily seek out females, but this brief social interaction ends after reproduction. Females show no parental care after laying eggs, leaving the hatchlings to fend for themselves.

Young Flying Geckos disperse shortly after hatching, immediately adopting the solitary lifestyle characteristic of their species. This independent behavior is common among many gecko species in the Gekkonidae family.

Their gliding adaptations – including skin flaps and webbed appendages – serve individual survival rather than group dynamics, allowing each gecko to escape predators and move between trees without assistance from others.

How do Flying Geckos communicate with each other?

Flying Geckos communicate through a mix of sounds, movements, and touch. These arboreal reptiles emit chirps, clicks, and squeaks to signal warnings, attract mates, and defend territory.

Their body language includes head bobbing, tail waving, and throat displays that clearly express intentions to other geckos in their vicinity. Males often use more elaborate displays during the breeding season.

Their sensitive dermal receptors detect subtle vibrations through substrates, creating a tactile communication network that enhances their social interactions. This specialized sensory system helps Flying Geckos (Ptychozoon kuhli) navigate their complex three-dimensional forest habitats while maintaining contact with conspecifics.

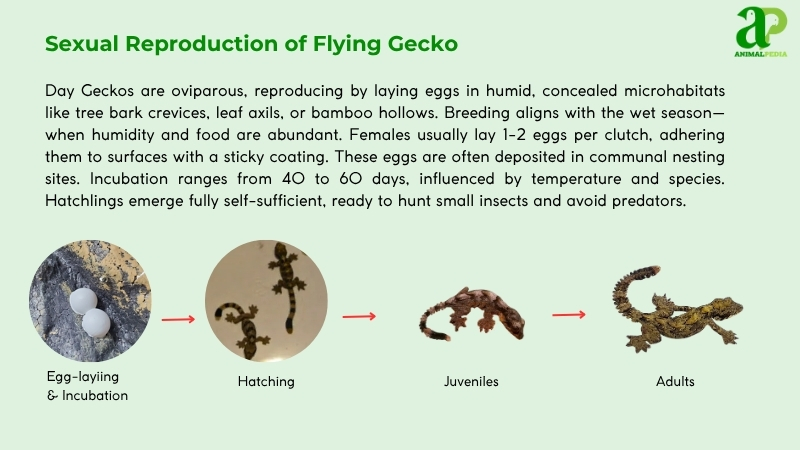

How do Flying Geckos reproduce?

Flying geckos reproduce oviparously, laying eggs after mating. Their breeding cycle begins during the wet season (March–May) in Southeast Asian rainforests. Males emit soft chirps and display territorial behaviors to attract females. Females signal readiness through subtle body movements, leading to brief courtship before mating occurs.

After successful reproduction, females lay two hard-shelled eggs, each weighing about 0.1 ounces (3 grams). They deposit these eggs in communal nesting sites, typically found in tree cavities or human structures, concealed with vegetation for protection. Neither parent provides nest guarding; both return to solitary lives. Recent field observations from Borneo (2019) show that egg-laying patterns can be disrupted by predators or habitat changes.

Incubation lasts 60–90 days. Hatchlings emerge measuring 1.5 inches (4 centimeters) and show precocial development, hunting tiny insects immediately without parental care. They reach sexual maturity in 6–8 months. Their lifespan ranges from 5–8 years, with shorter durations in natural habitats due to predation pressure. This reproductive strategy has evolved for rainforest conditions, ensuring species survival despite minimal parental investment.

How long do Flying Geckos live?

Flying Geckos’ lifespan is around 5 to 8 years in the wild, with some individuals reaching up to 10 years in captivity under optimal conditions. Lifespan appears comparable between males and females, though males may face more risks due to territorial aggression.

Longevity is influenced by habitat quality, predation pressure, and diet. These arboreal lizards exhibit rapid juvenile development, reaching sexual maturity within their first year, which supports their survival strategy in dynamic rainforest ecosystems.

What are the threats or predators that Flying Geckos face today?

Flying geckos face multiple threats in their Southeast Asian rainforest habitats. These pressures, combined with natural predation, challenge their survival. Human activities amplify these risks, as documented in recent studies.

- Habitat Loss: Deforestation for agriculture and logging destroys canopy habitats, reducing nesting and foraging sites, severely limiting population viability.

- Climate Change: Altered rainfall patterns disrupt breeding cycles and insect prey availability, stressing gecko populations in humid forests.

- Pet Trade: Overcollection for exotic pet markets depletes wild populations, particularly Ptychozoon kuhli, disrupting local ecosystems.

- Invasive Species: Introduced predators like rats compete for resources and prey on eggs, fragmenting gecko populations in isolated habitats.

Flying geckos are preyed upon by arboreal snakes (e.g., Boiga dendrophila), nocturnal birds (owls), and larger lizards. These predators exploit their small size and exposed nesting sites. Gliding and camouflage offer some defense, but predation is a significant risk.

Human-driven deforestation and urbanization fragment rainforest habitats, reducing gecko populations. A 2019 study by Brown and Diesmos notes that logging in Borneo and Sumatra has diminished Ptychozoon habitats by 20% since 2000. Pet trade exploitation further stresses populations, with thousands exported annually. Conservation efforts are critical to mitigate these impacts and preserve their ecological niche.

Are Flying Geckos endangered?

Most flying gecko species aren’t endangered, but face habitat threats in their natural environments.

The Ptychozoon genus, which includes Ptychozoon kuhli (Kuhl’s Flying Gecko), lacks a comprehensive IUCN assessment. Species like P. lionotum and P. trinotaterra are classified as Least Concern due to stable populations across Southeast Asian rainforests. However, populations in fragmented habitats are Data Deficient, requiring further research to evaluate localized extinction risks. The IUCN documents that 21% of assessed reptiles face extinction threats, with habitat destruction as the primary concern for arboreal geckos.

Precise population figures for flying geckos are unknown due to their cryptic behavior and canopy-dwelling habits. Brown and Diesmos (2019) report stable densities in pristine forests of Borneo with no significant population decline. Yet deforestation and wildlife trafficking have impacted specific populations, with Sumatran flying gecko numbers dropping by 20% since 2000. Continuous monitoring is essential for assessing their long-term conservation status.

What conservation efforts are underway?

Flying geckos face critical threats from habitat destruction and pet trade exploitation, spurring focused conservation initiatives across Southeast Asia. Since 2013, the Asian Species Action Partnership (ASAP) has coordinated protection efforts for Ptychozoon species, emphasizing forest preservation and anti-trafficking operations. The IUCN’s Species Survival Commission backs systematic monitoring to track population changes.

Indonesia implements strict harvest quotas on wild Ptychozoon specimens, restricting exports to fight commercial exploitation. Since 2019, CITES Appendix II proposals covering related gecko species have strengthened international trade regulations, banning unregulated wild collection. Enforcement includes heavy penalties and seizures, exemplified by Bhutan’s robust anti-trafficking legislation.

European and Australian zoological facilities, using ZIMS database guidance, maintain captive breeding colonies of Ptychozoon kuhli, with endangered species representing 20% of the 201 gecko species in managed care. A Singapore breeding program documented a 50% survival rate among hatchlings in 2022, enhancing genetic variability. Reintroduction experiments in Borneo show encouraging results, with nearly one-third of released specimens surviving beyond twelve months.

The successful recovery of the Monito gecko, removed from the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 2019 following invasive rat eradication, provides a blueprint for flying gecko conservation. ASAP’s habitat restoration work in Sumatra has yielded a 15% increase in local Ptychozoon observations since 2020. These conservation strategies, supported by TRAFFIC and IUCN, highlight the importance of coordinated protection measures to ensure flying geckos’ long-term survival.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Flying Geckos Actually Fly Like Birds or Bats?

Sure, flying geckos don’t really “fly” in the way birds or bats do; instead, they glide using their skin flaps. It’s more like controlled falling with some aerial maneuvering. They can’t take off mid-air like birds.

Are Flying Geckos Endangered or at Risk of Extinction?

Hey, don’t worry! Flying geckos aren’t endangered right now. They’re doing okay in their habitats. With proper conservation efforts and protection of their environments, these cool creatures can keep on thriving!

What Do Flying Geckos Eat in the Wild?

In the wild, flying geckos feed on insects like crickets, flies, and moths. They also consume some fruits and nectar. These creatures possess a diverse diet to guarantee their overall health and well-being.

Do Flying Geckos Make Any Sounds or Vocalizations?

Yes, flying geckos can vocalize by making soft chirping or squeaking sounds. These sounds are often used for communication or mating purposes. It adds an interesting element to their behavior and interaction within their habitat.

Can Flying Geckos Be Kept as Pets in Captivity?

Yes, flying geckos can be kept as pets in captivity. They require specific care and housing setups to thrive. Make sure to research their needs thoroughly before bringing one home to guarantee a happy and healthy flying gecko.

Conclusion

Flying Geckos exist as reptiles with distinctive gliding membranes, not actual wings. These arboreal specialists showcase spectacular coloration and evolved adaptations for aerial movement and predation. They inhabit tropical rainforests throughout Southeast Asia, where they employ their exceptional agility and precision to capture insects and small vertebrates.

These parachuting lizards serve crucial ecological functions as both predators and prey in forest canopy ecosystems. Their specialized lamellae provide superior climbing abilities while their patagium – the lateral skin fold – enables controlled aerial descent between trees.

Next time you explore Southeast Asian forests, scan the upper canopy for these nocturnal gliders in their natural habitat. Though rarely observed due to their cryptic behavior, witnessing a Flying Gecko (Ptychozoon spp.) in action reveals one of herpetology’s most fascinating evolutionary adaptations.