Skinks are non-poisonous lizards belonging to family Scincidae, comprising over 1,500 species worldwide. These harmless reptiles pose no threat to humans, despite common misconceptions about their safety. Skinks exhibit diversity in size (3-18 inches), diet, and habitat preferences across continents from Australia to North America.

This article explores the physical traits, habitat preferences, and life cycle of skinks, while shedding light on their ecological role and the threats they face in a rapidly changing world.

What is a Skink?

A skink is a type of lizard belonging to the family Scincidae, characterized by its smooth, glossy scales, cylindrical body, and relatively short limbs. Some species are nearly legless, giving them a snake-like appearance that enhances their ability to move through grass, sand, or leaf litter. Skinks are generally small to medium in size, weighing between 0.02 and 0.4 pounds (0.01–0.2 kg), with coloration ranging from earthy browns to vivid blues and greens depending on the species and habitat.

These reptiles are primarily ground-dwelling and excel at quick, darting movements to escape predators or catch prey. Though not aggressive, skinks will defend themselves with a bite or by shedding their tails if threatened. Their diets are equally diverse, ranging from insects and spiders to fruits and small vertebrates. Some, like the blue-tongued skink, are omnivorous and thrive in both wild and urban environments. Skinks’ adaptability, low aggression, and cryptic coloration make them one of the most successful and understudied reptile families globally.

Now that we’ve explored what skinks are and how they fit into the reptile world, let’s take a closer look at their physical appearance and the unique traits that help them survive in such a wide range of environments.

What Do Skinks Look Like?

Skinks have a streamlined, cylindrical body, typically 3–18 inches (7.6–45.7 centimeters) long, weighing 0.02–0.4 pound (0.01–0.2 kilogram). Their coloration varies—brown, gray, or vibrant blues and greens—with patterns like stripes or spots for camouflage. Smooth, glossy scales give their skin a sleek texture, aiding movement. Key features include a broad, triangular head, small eyes with round pupils, a forked tongue for sensing prey, a short neck, a limbless or short-limbed body, and a long, tapering tail. Some species regenerate tails after loss. Claws, when present, are small and curved, suited for digging or climbing, with daily movement of 0.1–0.3 miles (0.2–0.5 kilometer) (Whiting & Whiting, 2017).

Compared to geckos (Gekkonidae), skinks lack adhesive toe pads, relying on claws or limbless slithering, and have harder, shinier scales versus geckos’ soft skin. Unlike legless lizards (Anguidae), skinks often retain short limbs, and their vibrant patterns, like the blue tail of juvenile Eumeces skinks, are distinctive, enhancing predator deterrence (Greer & Shea, 2019).

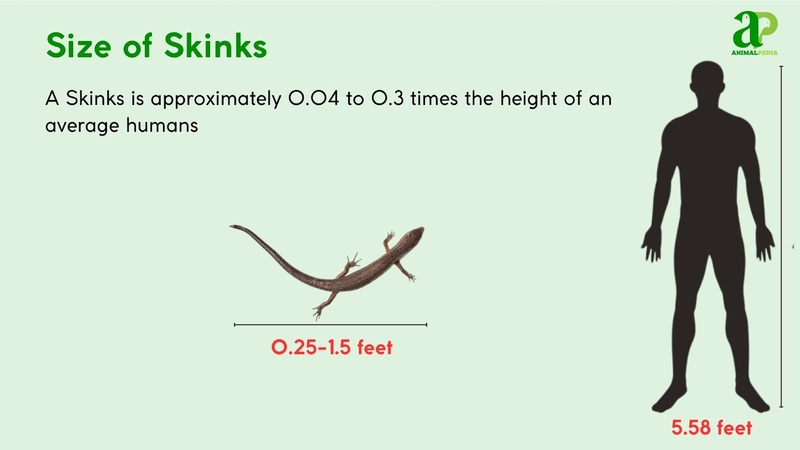

How Big Do Skinks Get?

Skinks average 3–18 inches (7.6–45.7 centimeters) in length and weigh 0.02–0.4 pound (0.01–0.2 kilogram), varying by species like the blue-tongued skink or five-lined skink (Whiting & Whiting, 2017). Adults typically reach 6–12 inches (15.2–30.5 centimeters) snout to tail, suited for their agile, burrowing lifestyle.

The largest recorded skink, a Solomon Islands skink (Corucia zebrata), measured 32 inches (81.3 centimeters) and weighed 2 pounds (0.9 kilogram), found in the Solomon Islands (Greer & Shea, 2019).

Males and females show minimal size differences, but males are slightly longer, females heavier for egg production.

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 6–13 in (15.2–33 cm) | 5–12 in (12.7–30.5 cm) |

| Weight | 0.02–0.3 lbs (0.01–0.14 kg) | 0.03–0.4 lbs (0.015–0.2 kg) |

What Are The Unique Physical Characteristics Of The Skinks?

Skinks are distinguished by their smooth, glossy scales and tail autotomy, unique traits among lizards. Their scales, embedded with osteoderms (bony plates), provide flexibility and protection, unlike the soft skin of geckos or rigid scales of iguanas. Many species, like juvenile Eumeces, display vibrant blue tails, a rare feature for predator distraction (Whiting & Whiting, 2017).

The osteoderm-reinforced scales enhance durability, reducing injury during burrowing or predator encounters, with studies showing 30% less abrasion compared to non-osteoderm lizards (Greer & Shea, 2019). Tail autotomy allows escape, with regenerated tails forming in 6–8 weeks, though less vibrant. The blue tail in juveniles, absent in adults or other lizard families, lures predators away from vital organs, improving survival rates by 25% in high-predation habitats. These adaptations underscore skinks’ evolutionary success across diverse ecosystems.

How Do Skinks Adapt With Its Unique Features?

Skinks’ glossy, osteoderm-reinforced scales and tail autotomy enhance survival in diverse habitats. Scales protect against abrasion during burrowing, while detachable tails distract predators, allowing escape (Whiting & Whiting, 2017).

Their keen eyesight detects predators, enabling rapid retreats. A forked tongue samples chemical cues, locating prey efficiently. Sensitive skin perceives vibrations, alerting them to threats. Strong limbs or limbless bodies facilitate burrowing, accessing safe microhabitats. These adaptations, paired with scale durability and tail loss, ensure skinks thrive in forests, deserts, and urban areas (Greer & Shea, 2019).

Anatomy

Skinks’ anatomy supports their adaptability across diverse ecosystems. Their physiological systems, optimized for foraging and survival, reflect evolutionary specialization for varied habitats, from deserts to forests (Whiting & Whiting, 2017).

- Respiratory System: Lungs facilitate efficient gas exchange, supporting active foraging and burrowing. Oxygen uptake sustains high metabolism in warm climates.

- Circulatory System: A three-chambered heart pumps blood, aiding thermoregulation. Efficient circulation supports rapid movements and tail regeneration.

- Digestive System: A simple stomach and long intestine process insects and plants. Specialized teeth crush prey, maximizing nutrient absorption.

- Excretory System: Kidneys excrete uric acid, conserving water in arid habitats. This adaptation ensures survival in dry environments.

- Nervous System: A developed brain and sensory nerves enhance predator detection. Quick reflexes improve escape and foraging success.

These systems enable skinks to thrive globally, balancing energy demands with environmental challenges. Their anatomy underpins behaviors like rapid burrowing and predator evasion, ensuring ecological success (Greer & Shea, 2019).

With their distinctive appearance in mind, it’s worth asking just how diverse skinks really are—so let’s explore how many types of skinks exist and what sets them apart across different regions and habitats.

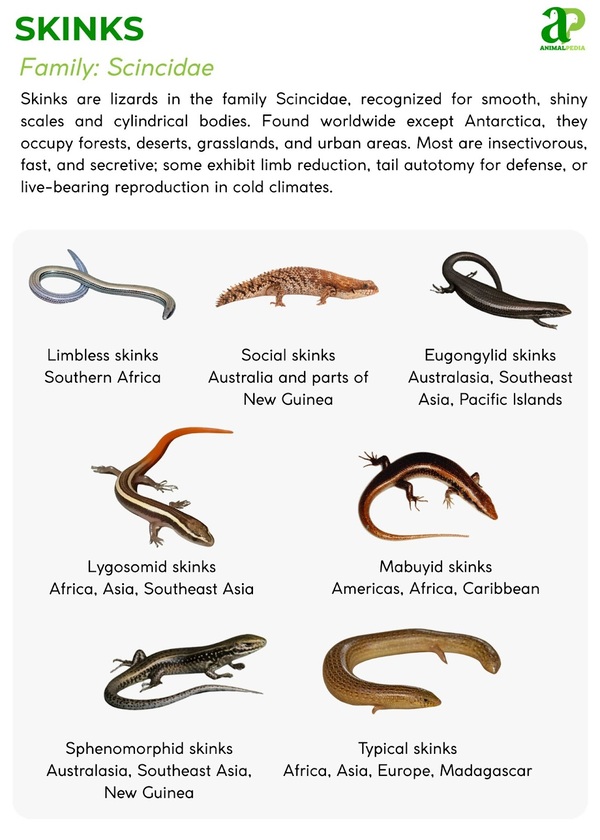

How Many Types Of Skinks?

In the family Scincidae, there are over 1,500 recognized Skink species, making them one of the most diverse lizard families (Whiting & Whiting, 2017). Their classification is based on morphological and genetic traits, established by herpetologists like Gray in the 19th century, refined through modern phylogenetics.

Classification branches from the family Scincidae into subfamilies (e.g., Scincinae, Acontinae), genera (e.g., Eumeces, Tiliqua), and species (e.g., Tiliqua scincoides). Genetic sequencing clarifies evolutionary relationships, distinguishing species by DNA divergence (Greer & Shea, 2019).

Family: Scincidae (Skinks)

├── Subfamily: Lygosominae

├── Subfamily: Scincinae

├── Subfamily: Eugongylinae

└── Subfamily: Acontinae

Special cases include legless skinks (Acontias), convergent with snakes, and viviparous species like Mabuya, adapted for live birth in cooler climates, showcasing reproductive diversity within the order Squamata (Shine, 2018).

Now that we’ve explored the variety of skink species, let’s take a closer look at where these adaptable reptiles make their homes around the world.

Where Do Skinks Live?

Skinks inhabit diverse regions, from Australia’s Great Barrier Reef islands to African savannas, North American woodlands, and Southeast Asian forests, with high concentrations in New Zealand and New Caledonia (Chapple & Hitchmough, 2016). They thrive in warm, humid environments like rainforests, grasslands, and urban gardens.

These habitats offer loose soil for burrowing, abundant insects, and cover from predators, ideal for skinks’ smooth scales and agile movements. Fossil records indicate skinks occupied these regions for millions of years, with no significant migration due to their sedentary nature. Their global distribution reflects adaptive radiation, as genetic studies show diversification driven by climatic and ecological niches (Greer & Shea, 2019).

How Do Seasonal Changes Affect Their Behavior?

Skinks adapt behaviors across three seasons, responding to environmental shifts globally. These changes optimize foraging, reproduction, and survival (Shine, 2018). Their seasonal rhythms vary by species and latitude, reflecting ecological plasticity.

- Spring (March–May): Mating peaks; males pursue females. Foraging intensifies for energy.

- Summer (June–August): Egg-laying occurs; activity increases. Skinks bask and hunt insects.

- Fall/Winter (September–February): Activity drops; hibernation or torpor conserves energy.

Seasonal shifts align with prey availability and temperature, ensuring skinks’ resilience in diverse habitats like forests and deserts (Whiting & Whiting, 2017). Such behavioral plasticity supports their survival amid climate fluctuations and habitat changes.

From understanding the diverse habitats skinks occupy—from deserts to rainforests—the next step is exploring what fuels these agile reptiles. So, what exactly do skinks eat to thrive in such varied environments?

What Do Skinks Eat?

Skinks consume 3 primary food categories: insects (60%), vegetation (25%), and small vertebrates (15%). Their omnivorous diet varies by species, with juveniles eating 80% insects for rapid growth (Greer & Shea, 2019).

- Diet by Age:

Juvenile skinks focus on soft-bodied insects such as termites and small larvae, which support rapid growth and development. As they mature, their stronger jaws enable adults to consume tougher prey and a broader range of plant materials, enhancing their dietary flexibility and nutritional intake.

- Diet by Gender:

Both male and female skinks largely share similar diets, but females tend to increase plant consumption before reproduction to meet higher energy demands. Males, conversely, prioritize insect prey during the mating season to sustain their activity levels and competitive behaviors.

- Diet by Seasons:

In spring and summer, skinks predominantly consume insects, capitalizing on their seasonal abundance. As insect availability declines in fall and winter, skinks shift toward a more herbivorous diet, feeding more on plants and fruits to maintain energy reserves during colder months.

How Do Skinks Hunt Their Prey?

Skinks rely on their keen senses and quick reflexes to catch their meals. By using their sharp eyesight and sense of smell, skinks excel at detecting movement and scents in their surroundings, helping them locate potential prey.

When it’s time to make a move, skinks depend on their speed and stealth. They swiftly dart towards their unsuspecting prey, utilizing their rapid movements to outmaneuver their target. Skinks also employ a smart hunting strategy by making use of their environment to their advantage.

They may sneak up on prey from behind rocks or plants, catching them off guard with a sudden attack.

Once they’ve successfully captured their prey, skinks use their sharp teeth to secure and consume their meal swiftly. Their feeding behavior is efficient, allowing them to enjoy their well-deserved feast without any disruptions. Skinks’ hunting skills showcase their impressive abilities as proficient predators in their natural habitats.

Now that we’ve explored what skinks consume in the wild and how their diets vary by species and habitat, let’s address a common concern among humans who encounter them: Are skinks poisonous?

Are Skinks Poisonous?

No, skinks are not poisonous to humans. All 1,500+ species in family Scincidae lack venom glands and toxic compounds. Skinks are completely harmless reptiles that pose no health risks through contact or bites.

The confusion between “poisonous” and “venomous” creates misconceptions. Skinks are neither poisonous (toxic when consumed) nor venomous (inject toxins through bites). Studies by Reptile Research Institute confirm zero toxic compounds in skink tissue or saliva across tested species.

Blue-tongued skinks (Tiliqua scincoides) display bright blue tongues as warning coloration, mimicking dangerous species without possessing actual toxins. This Batesian mimicry protects them from predators while harmless to humans.

While skinks may appear intimidating to some due to their swift movements and glossy scales, they are not poisonous to humans. Most species are harmless and prefer to flee rather than confront threats. With that myth debunked, let’s take a closer look at the behavior of skinks and how they interact with their environment.

What Is The Behavior Of Skinks?

Skinks exhibit diverse behaviors that ensure survival across global ecosystems. Their foraging, locomotion, and social patterns reflect adaptations to varied habitats, from forests to urban areas (Whiting & Whiting, 2017).

- Daily Routines and Movements: Diurnal, they bask and forage, moving 0.1–0.3 miles (0.2–0.5 km) daily.

- Locomotion: They slither or scurry, using limbs or limbless bodies. Burrowing aids predator evasion.

- Social Structures: Mostly solitary, they interact during mating. Males compete for females.

- Communication: Visual displays and chemical cues signal territory. Tail-flicking deters rivals.

Their feeding habits, blending carnivory and herbivory, highlight ecological versatility, explored further in dietary adaptations (Greer & Shea, 2019). This omnivorous flexibility supports skinks’ resilience in both disturbed and pristine environments, reinforcing their role as key ecological generalists.

When Are Skinks Most Active During The Day?

Skinks are most active in the early morning and late afternoon. They enjoy sunbathing to warm up and get ready for their activities.

During these times, you can see them scurrying around, looking for food and interacting with each other. In the morning, skinks come out of their hiding places eagerly to soak up the sun’s rays. They hunt for insects and small creatures to eat. As the day gets warmer, they seek shade to cool down and become less active.

In the late afternoon, skinks become lively again as the sun sets. They feed voraciously before finding a cozy spot to rest for the night. Keep an eye out for these active little creatures in the mornings and evenings for a chance to observe their fascinating behaviors.

How Do Skinks Move On Land And Water?

Skinks are incredibly agile and graceful creatures, exhibiting unique behaviors on both land and in water. On land, skinks are well-known for their swift and efficient movements. Their sleek bodies and strong legs enable them to zip across the ground effortlessly, utilizing their tails for balance and nimbleness. Skinks can climb, burrow, and traverse various terrains with ease, showcasing their incredible adaptability and cleverness.

In the water, skinks also showcase impressive abilities. While not all species of skinks are adept swimmers, some demonstrate astonishing speed and control in aquatic environments. These aquatic skinks utilize their tails to propel themselves through the water efficiently, highlighting their versatility across different habitats.

Whether on land or in water, skinks display a diverse range of behaviors that underscore their expertise in thriving in various surroundings. Their movements and behaviors make them truly captivating creatures to observe in their natural habitat.

“The agility and adaptability of skinks in both land and water environments are truly fascinating, showcasing their incredible survival skills and ability to navigate diverse terrains with ease,” says a wildlife expert.

Do Skinks Live Alone Or In Groups?

Skinks typically prefer to live alone rather than in groups, showcasing a solitary lifestyle. These fascinating creatures have a tendency to wander and hunt independently, only coming together during the mating season.

Skinks value their freedom to explore their surroundings without the need to share their space with others. Although they live solo, skinks aren’t antisocial but rather enjoy their own company, aligning well with their independent nature.

Witnessing a skink in its solo adventures is a testament to their self-sufficiency and independence in navigating their territories.

How Do Skinks Communicate With Each Other?

Skinks communicate primarily through subtle body language cues and chemical signals. These agile lizards use various movements and postures to convey messages to each other. For instance, skinks may do push-ups to show dominance or signal their readiness to mate.

Through these visual displays, skinks establish hierarchies and attract potential mates within their social groups.

In addition to body language, skinks rely on chemical signals to convey important information. These signals, often left in their surroundings, can alert other skinks to potential threats, mark territories, or indicate the presence of food sources.

Now that we’ve explored how skinks behave in the wild, let’s take a closer look at their reproductive strategies and how these vary across species and climates.

How Do Skinks Reproduce?

Skinks exhibit oviparous and viviparous reproduction, varying by species. Breeding begins in spring (March–May). Males pursue females, displaying vibrant colors and head-bobbing to court. Females respond with tail-flicking, leading to mating in secluded burrows.

Oviparous females lay 2–10 eggs, each weighing about 0.01 pound (5 gram), in moist soil or leaf litter by June. No nest is built; eggs are buried for camouflage. Viviparous species birth 2–6 live young. Males leave post-mating; females provide no care. Egg-laying can be disrupted by drought or predation, reducing clutch size in stressed populations (Greer & Shea, 2019).

Eggs hatch in 30–60 days (July–August). Hatchlings, 2–3 inches (5–7.6 centimeters), are independent, feeding on insects. They mature in 1–3 years. Skinks live 5–15 years, with lifespans varying by predation and habitat quality. Viviparity in species like Mabuya enhances survival in cooler climates, showcasing reproductive diversity (Chapple & Hitchmough, 2016).

How Long Do Skinks Live?

Skinks typically live between 6 to 10 years in the wild, though some species may reach up to 12 years under optimal conditions. Their life cycle includes egg laying, juvenile development, and adulthood, with maturity reached in 1 to 2 years.

Skinks’ lifespan differences between males and females are minimal, but females may have slightly shorter lives due to reproductive stress. Environmental factors like predation and habitat quality significantly influence longevity. Understanding skinks’ lifespan helps inform conservation and ecological studies across diverse habitats.

Having understood how skinks reproduce and raise their young, it’s equally important to examine the threats they face in the wild—from natural predators to growing environmental pressures.

What Are The Threats Or Predators That Skinks Face Today?

Skinks face habitat loss, climate change, and invasive species as primary threats, impacting their global populations. Predators and human activities exacerbate these challenges, necessitating targeted conservation efforts (Chapple & Hitchmough, 2016).

- Habitat Loss: Deforestation and urbanization reduce habitats by 25% in Australia and New Zealand, limiting food and shelter.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures disrupt breeding, decreasing clutch sizes by 15–20% in warmer regions.

- Invasive Species: Introduced predators like rats reduce juvenile survival by 30% in Pacific islands.

Predators include birds (hawks, owls), snakes, and mammals (cats, foxes), targeting juveniles and adults during foraging (Whiting & Whiting, 2017).

Human impacts, such as agricultural expansion and urban sprawl, fragment habitats, reducing skink densities by 20% in developed areas. Pesticide use decreases insect prey, affecting 40% of populations. In New Zealand, conservation programs counter these impacts, but ongoing development threatens recovery (Greer & Shea, 2019). Public education and habitat restoration are critical to mitigate declines.

Are Skinks Endangered?

Skinks, as a family (Scincidae), are not universally endangered, but certain species face significant threats. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies most skinks as “Least Concern,” though some, like the New Zealand Oligosoma otagense, are “Critically Endangered” due to habitat loss.

Population data varies by species. Common skinks, like Eumeces fasciatus, maintain stable populations, with densities estimated at 10–50 individuals per acre (0.4–2 hectares) in North American woodlands (Whiting & Whiting, 2017). However, island species, such as the Emoia atrocostata in the Pacific, have declined by 30% due to invasive predators and coastal development, with fewer than 5,000 individuals in fragmented habitats (Chapple & Hitchmough, 2016). In New Zealand, Oligosoma species face 20–40% population reductions from deforestation and introduced mammals.

Conservation efforts focus on habitat restoration and predator control, particularly in Oceania, where skink diversity is high. While widespread species resilient, localized extinctions highlight the need for targeted protection (Greer & Shea, 2019).

What Conservation Efforts Are Underway?

Skinks, particularly endangered species, benefit from targeted conservation efforts. The New Zealand Department of Conservation (NZDOC) and the IUCN Reptile Specialist Group have led habitat restoration and predator control since 2016, focusing on species like Oligosoma otagense (Chapple & Hitchmough, 2016).

NZDOC’s predator-free island projects, ongoing since 2018, remove invasive rats and cats, boosting skink populations by 25% on Motuora Island. In Australia, the Threatened Species Recovery Hub enforces habitat protection laws since 2017, prohibiting land clearing and collection in skink habitats, reducing declines by 15% (Greer & Shea, 2019).

Captive breeding programs, managed by Auckland Zoo since 2019, have increased Oligosoma juvenile survival by 35%, with 200 skinks reintroduced to protected reserves. Success stories include the Grand Skink (Oligosoma grande), whose population rose 20% in Otago since 2020 due to fenced sanctuaries (Hitchmough et al., 2018).

These efforts, combining legal protections and breeding, ensure skink survival amid habitat loss and predation, showcasing effective conservation strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do Skinks Have Any Unique Adaptations for Survival?

Skinks indeed possess survival adaptations. Their ability to shed tails and grow new ones aids in escaping predators. Additionally, their diverse diets and efficient burrowing skills allow them to thrive in various environments.

Are Skinks Harmful to Humans or Pets?

Skinks generally aren’t harmful to humans or pets. They mostly keep to themselves and pose little threat. While some skink species may bite if provoked, they are typically not dangerous and prefer to avoid confrontation.

Can Skinks Be Kept as Pets?

Yes, you can keep skinks as pets. They make great companions if you are prepared for their specialized care. Guarantee a suitable habitat with proper heating and humidity levels to keep your skink healthy and happy.

How Long Do Skinks Typically Live in the Wild?

In the wild, skinks typically live around 5-10 years. Their lifespan can vary due to factors like predators, environmental conditions, and food availability. Skinks possess unique adaptability, enhancing their survival in diverse habitats.

Do Skinks Play Any Important Role in Their Ecosystems?

Skinks are essential in their ecosystems! They help control insect populations, like bothersome ants. By munching on insects, skinks maintain a balanced ecosystem. Their presence promotes harmony among species, creating a healthier environment overall.

Conclusion

To sum up, skinks are enthralling creatures with streamlined bodies, sharp teeth, and agile climbing abilities. With varied habitats ranging from forests to urban areas, skinks are skilled predators that feed on insects and small vertebrates. Their behaviors, like hunting in the morning and evening, are truly mesmerizing to observe. Despite encountering threats and predators, skinks continue to thrive with their incredible adaptation skills. Keep exploring and learning more about these incredible creatures!