Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) are ancient reptiles that represent the sole surviving member of the order Rhynchocephalia, a lineage dating back over 200 million years. These creatures belong to the class Reptilia and phylum Chordata, distinguishing them from lizards despite superficial similarities in body form. Adults measure 24 to 31 inches (61 to 80 cm) in length and weigh between 1.1 and 2.9 pounds (0.5 to 1.3 kg), with males larger than females.

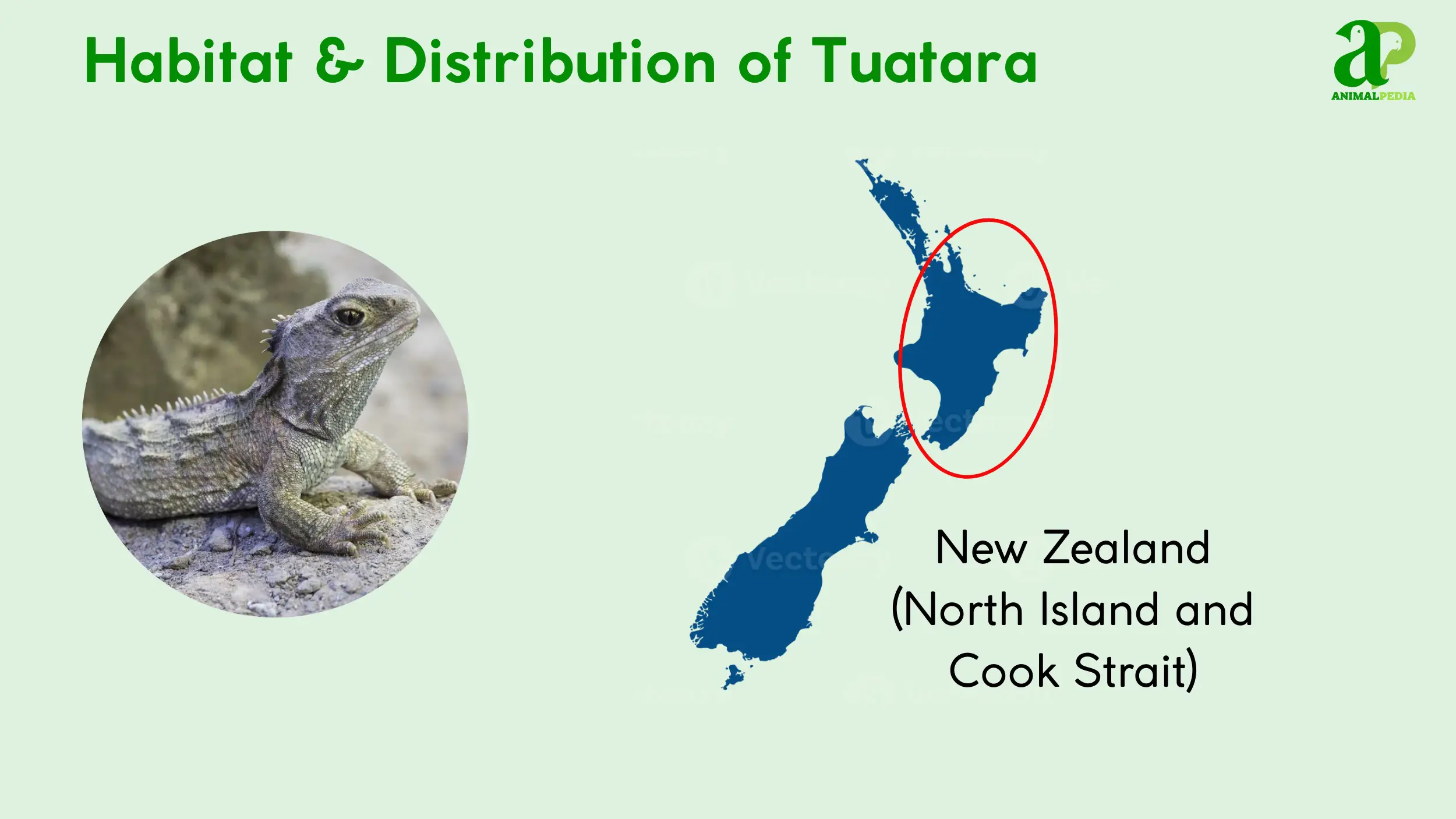

They inhabit offshore islands in New Zealand, particularly around the North Island and Cook Strait, where coastal forests provide essential burrows. Their diet consists mainly of insects and arthropods, supplemented by small lizards, seabird eggs, and earthworms, making them carnivorous opportunists.

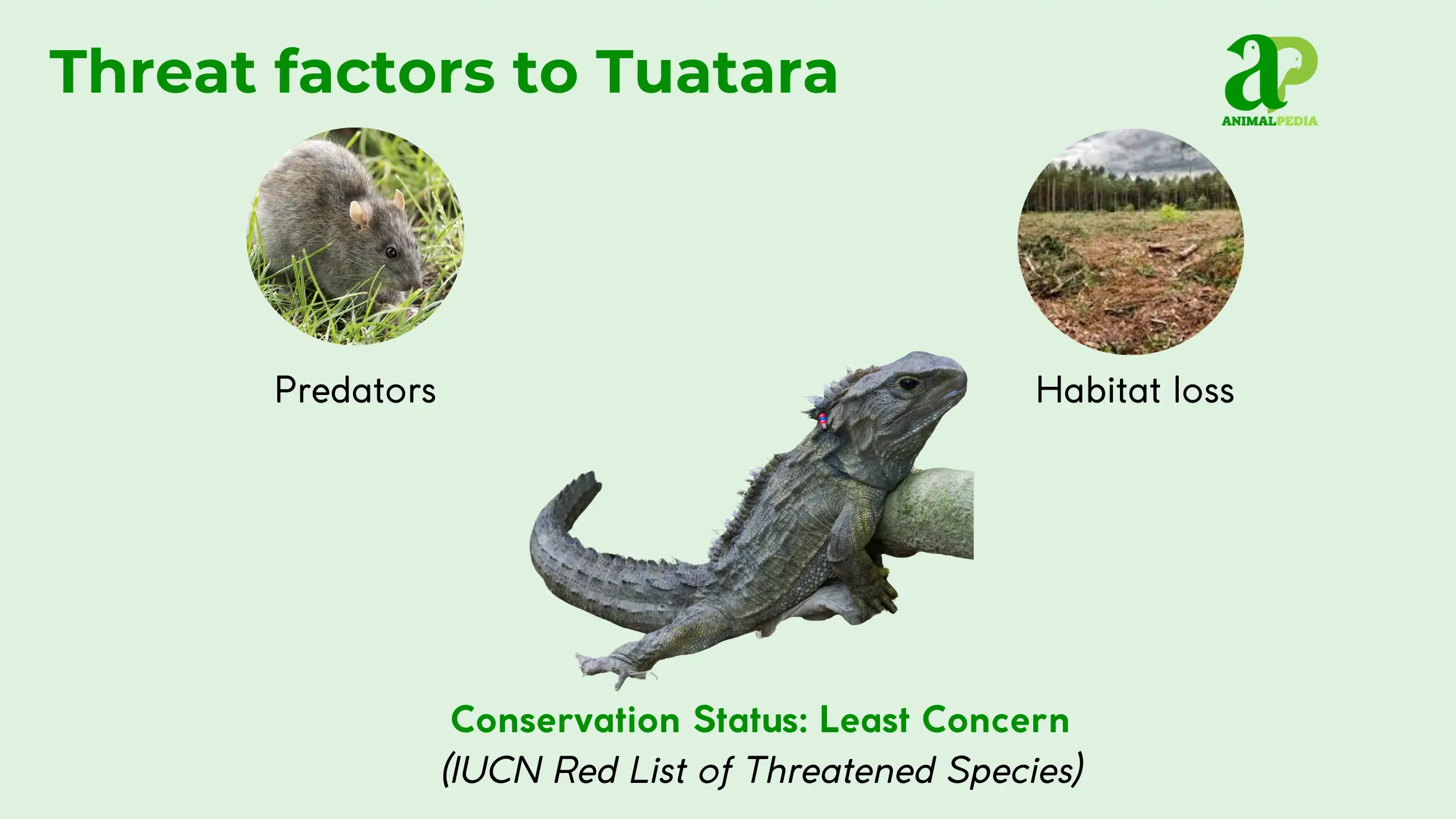

Tuatara move slowly on land with a top speed of 5 to 10 miles per hour (8 to 16 km/h) in bursts, relying on sturdy limbs for burrowing. They exhibit nocturnal patterns, emerging at night to hunt while basking during cooler days, and hibernate in winter. Conservation status lists them as Least Concern by IUCN, yet threats like invasive predators demand ongoing protection efforts.

This comprehensive guide delves into their unique third eye, natural habitat, and key facts to enhance understanding of this evolutionary relic. Discover how these features shape their survival in modern ecosystems. Now, examine the parietal eye that sets tuatara apart from other reptiles.

What Are Tuatara?

Tuatara, scientifically known as Sphenodon punctatus, is a species of reptile endemic to New Zealand that exhibits a distinct parietal eye and an ancient taxonomic lineage. They are the sole surviving species of the order Rhynchocephalia, a reptile group that flourished during the Mesozoic Era. The common name “tuatara” originates from the Māori language, reflecting the prominent spiny crest along its back.

The scientific classification places the tuatara within the Family Sphenodontidae, making it a unique evolutionary anomaly with no direct living relatives. Research has confirmed this reptile’s distinct status; a 2020 genome study revealed that the tuatara diverged from snakes and lizards approximately 240 million years ago, preserving many primitive amniote features, such as a large genome of approximately 5 Gb (2). There has been debate over whether tuatara should be classified as one or two species, but recent genetic analysis has shown that insufficient divergence exists to justify a two-species classification.

The tuatara is a true reptile, but its unique biology has led some to label it a “living fossil,” a term that is still debated within the scientific community. While its morphology has changed little over millions of years, its genetics and biology have continued to evolve.

The animal’s evolutionary history is a subject of ongoing study, offering insights into reptile evolution. Studies continue to explore its unique reproductive system, including the first characterization of its sperm (8), and its dietary habits (9). As a result of these in-depth studies, our understanding of this species continues to deepen, moving beyond its initial description and classification.

The tuatara’s physical appearance holds the secrets to its survival. From its spiny crest to its unique skull, every feature plays a vital role.

What Do Tuatara Look Like?

The tuatara is a robust, lizard-like reptile with a distinctive spiny crest running along its back, from the nape of its neck to the base of its tail. Its body is covered in a skin composed of small, beaded scales, providing a rough, textured feel and offering a range of colors from greenish-gray to olive-brown. The coloration often features small white or yellowish spots, which provide camouflage within their island habitats, blending seamlessly with the soil and leaf litter.

Research into the tuatara’s skin has provided insights into the early evolution of amniote skin, showing that the reptile possesses unique differentiation genes for its outer layer (10). While its overall morphology is similar to a lizard, its anatomical features, such as a rigid skull with an immovable quadrate bone, differentiate it from modern lizards and reflect its unique evolutionary path (7).

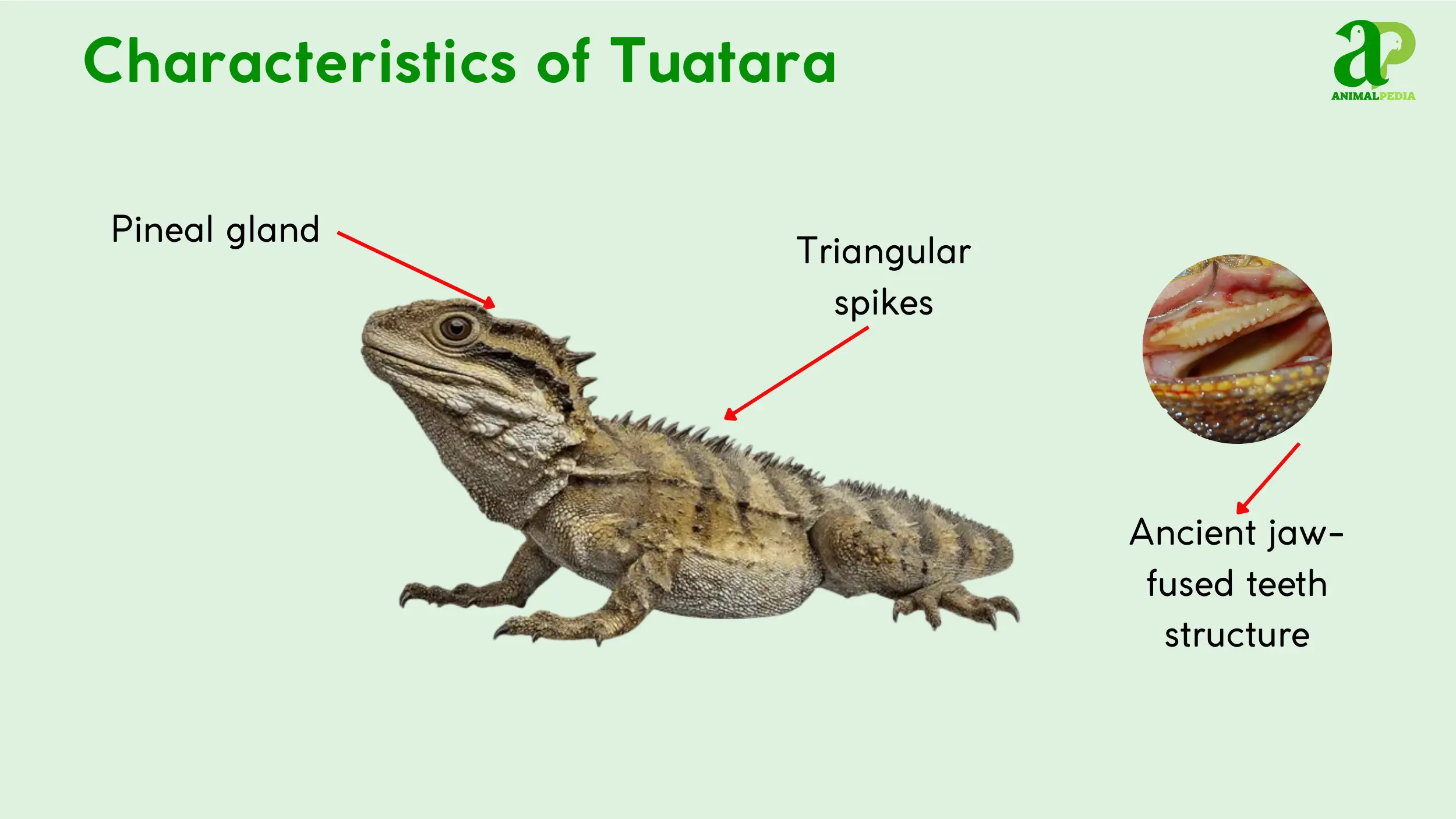

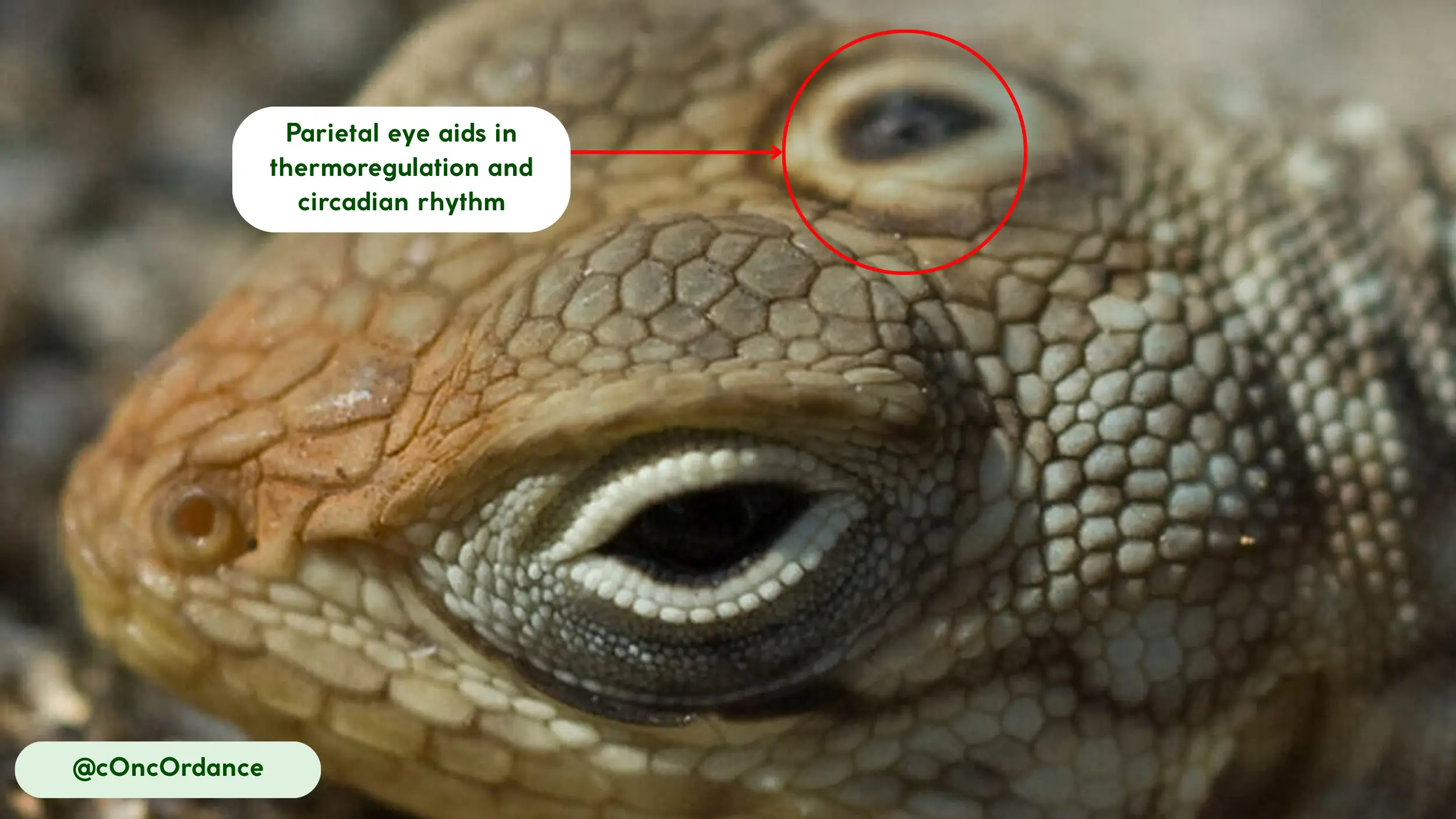

The tuatara possesses three distinct physical characteristics that set it apart from other reptiles: the parietal eye, its unique dentition, and the spiny crest.

- Parietal Eye: This photoreceptive organ on the top of its head, also called the pineal gland, is covered by translucent scales in adults. While not capable of seeing images, it is believed to detect changes in light intensity and UV radiation, which helps regulate the animal’s circadian rhythms and melatonin production (10). The tuatara’s slow metabolism and nocturnal habits are directly linked to this organ’s function.

- Acrodont Dentition: The tuatara’s teeth are an ancient feature, fused directly to the jawbone rather than set in sockets. This dentition, which remains unchanged throughout its life, enables it to produce a unique chewing motion, capable of shearing through tough arthropod exoskeletons (9). As the tuatara ages and its teeth wear down, its diet shifts to softer food sources.

- Spiny Crest: The word tuatara means “peaks on the back” in the Māori language, directly referencing the prominent triangular spikes that run along its neck and back. This feature, more pronounced in males than females, is used in defensive displays and territorial posturing.

Male tuatara exhibit more pronounced crests and are noticeably larger and heavier than females, a clear example of sexual dimorphism in the species. While its appearance is striking, the sheer size of the tuatara is also a significant aspect of its biology. Next, learn how big this reptile can get.

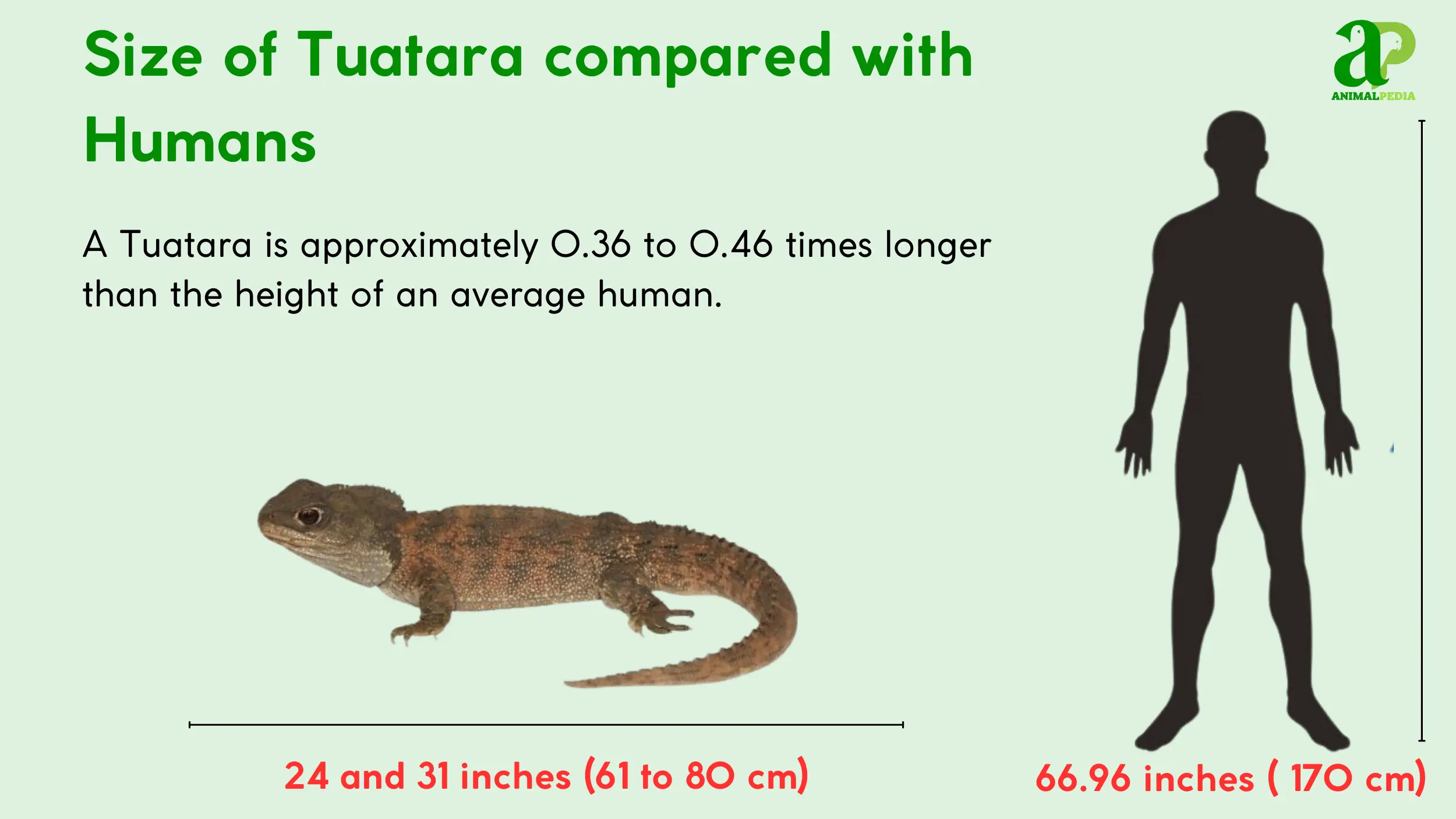

How Big Are Tuatara?

Adult tuatara typically measure between 24 to 31 inches (61 to 80 cm) in total length. They are stout reptiles, with a body weight ranging from 1.1 to 2.9 pounds (0.5 to 1.3 kg), and are among the heavier reptiles of their size.

A hatchling tuatara is small, weighing less than 0.2 ounces (5 grams) and measuring only a few inches (cm) long, roughly the size of a human finger. They grow slowly, taking decades to reach full maturity. An adult tuatara can be compared in size to a common house cat.

| Feature | Male | Female |

| Length | Up to 31 in (80 cm) | Up to 24 in (61 cm) |

| Weight | 1.8 to 2.9 lbs (0.8 to 1.3 kg) | 1.1 to 1.8 lbs (0.5 to 0.8 kg) |

| Record Size | The largest on record measured 39 inches (99 cm) and weighed 3.3 lbs (1.5 kg). |

Their size and physical traits are directly connected to the specific environments where they live. Discover how these island habitats shape their existence.

Where Do Tuatara Live?

Tuatara are native to New Zealand, inhabiting about 32 predator-free offshore islands. These islands, primarily off the coast of the North Island and in the Cook Strait, serve as their last remaining natural strongholds after their mainland populations were driven to extinction by invasive predators (13).

They live in coastal forests and shrublands, where they dig their own burrows or, more commonly, share burrows with seabirds, such as petrels and shearwaters. This symbiotic relationship provides them with food scraps and fertilizer from bird droppings.

Tuatara are well-adapted to cooler climates; their metabolism is so low that they can be active in temperatures as low as 5°C (41°F) (4). Despite this, they are territorial, with adult males defending their burrows and surrounding areas from other males.

The tuatara’s behavior is a direct result of its ancient evolutionary history and its island habitat. Their daily movements and seasonal patterns offer a glimpse into a world unlike any other reptile’s.

How Do Tuatara Behave?

The behavior of tuatara is characterized by adaptations to their unique environment and a slow metabolism that dictates their pace of life and rhythms. Their predatory instincts, movement, and daily patterns are all tailored to their niche as nocturnal, cool-weather reptiles.

- Diet and Feeding: Tuatara are opportunistic carnivores, primarily eating insects and other invertebrates, using a specialized jaw and unique dental structure to shear and chew their prey (9).

- Movement and Abilities: They are generally slow-moving but can achieve short bursts of speed, and they are excellent burrowers, often sharing their subterranean homes with seabirds.

- Daily/Seasonal Patterns: Their activity is mainly nocturnal, influenced by ambient temperatures, and they enter a state of dormancy during colder winter months.

To understand how these behaviors define the tuatara, we first examine their feeding habits.

Diet and Feeding

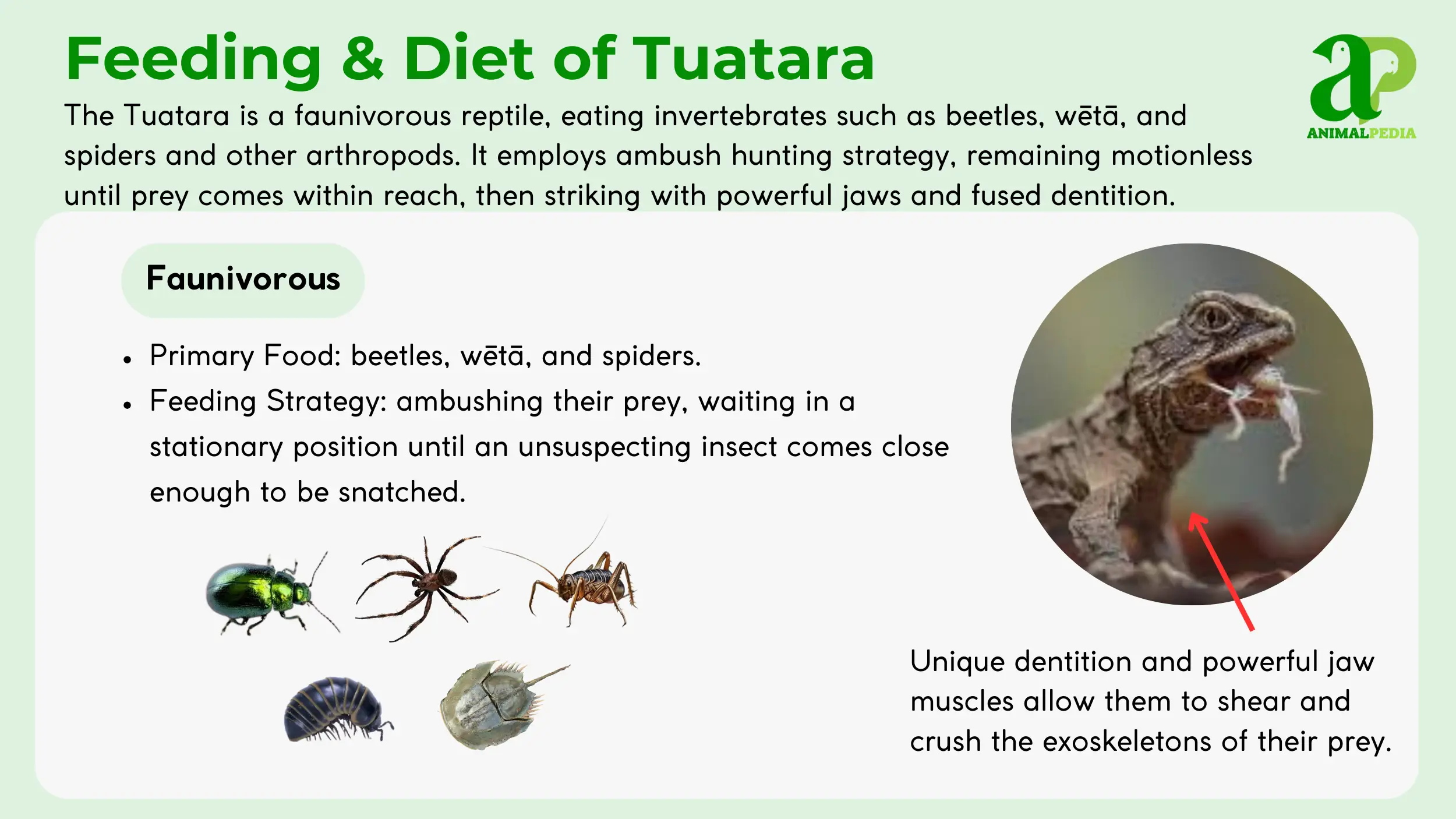

Tuatara are opportunistic carnivores that primarily consume invertebrates, with their diet classified as faunivorous. Their main prey includes beetles, wētā, spiders, and other arthropods. Research from 2022 on a New Zealand tuatara population showed that their morphological characteristics, particularly a wide head, were linked to a diet that included tougher prey (9).

They hunt by ambushing their prey, waiting in a stationary position until an unsuspecting insect comes close enough to be snatched. Their unique dentition and powerful jaw muscles allow them to efficiently shear and crush the exoskeletons of their arthropod prey.

While invertebrates form the bulk of their diet, tuatara also consume small lizards, seabird eggs, and chicks when available. This opportunistic behavior highlights their adaptability as a predator within their island ecosystems.

Studies have even explored the gut bacterial response of tuatara to changes in their diet (3). The ability to consume a wide range of prey helps them thrive in environments with fluctuating food availability.

Movement and Abilities

Tuatara move with a characteristic slow, deliberate gait. They are known for their sturdy limbs and slow pace, which is a result of their low metabolic rate.

While generally slow, they are capable of surprising bursts of speed when startled or pursuing prey. Tuatara can run at speeds up to 5 miles per hour (8 km/h). Their physical capabilities also include exceptional burrowing skills.

Their special abilities include their highly effective burrowing behavior and the parietal eye, which, as noted previously, aids in thermoregulation and circadian rhythm. The ability to dig extensive burrow systems or cohabitate with seabirds provides protection from predators and temperature fluctuations.

Daily/Seasonal Patterns

Tuatara are primarily nocturnal, with activity peaking after sunset and ceasing before sunrise. Their activity patterns are highly dependent on environmental temperatures. They are most active during warmer months, specifically the spring and summer.

During the day, they often bask near their burrow entrances to warm up, a behavior known as heliothermy. Their low metabolic rate allows them to stay active in cooler conditions, with some tuatara observed foraging at temperatures as low as 41°F (4).

Their seasonal activity varies significantly. They are most active during New Zealand’s spring and summer, from October to February, when temperatures are higher and food is abundant. In winter, they become largely inactive, entering a state of brumation (a reptilian hibernation) within their burrows to conserve energy.

Tuatara are non-migratory. They spend their entire lives within a small territory, typically centered around a burrow system. Research on tuatara translocations shows they adapt to new locations within their historic range, but do not naturally migrate over long distances (4).

The intricate behaviors of the tuatara, from their hunting habits to their burrowing skills, all lead to the ultimate goal of survival and reproduction. Learn about their slow but steady reproductive process.

How Do Tuatara Reproduce?

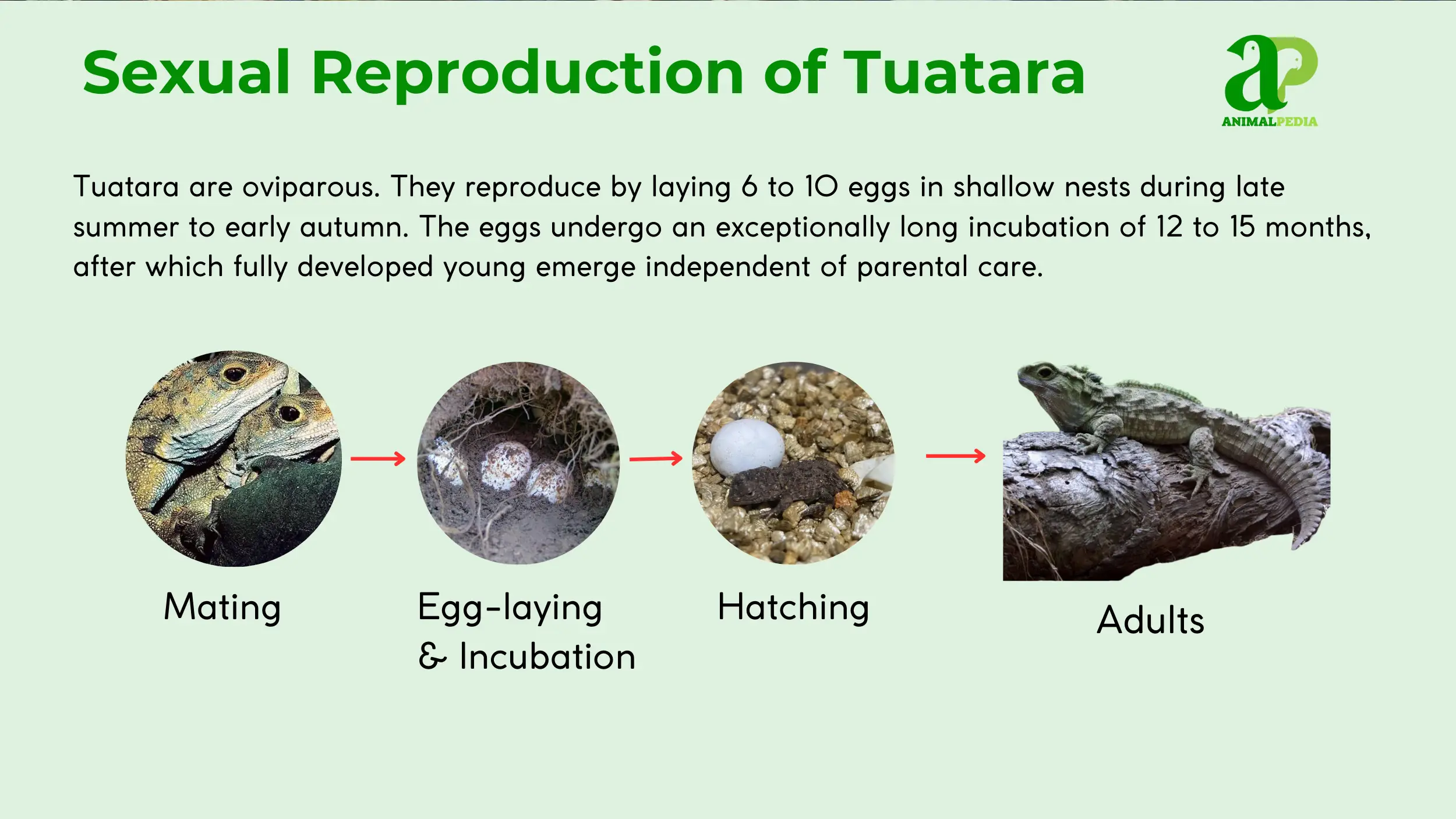

Tuatara are oviparous, meaning they lay eggs. Reproduction is a slow process for the species. Mating typically occurs in the late summer and early autumn (January to March) when males engage in territorial displays, including aggressive posturing and spine-raising, to attract females. Females lay clutches of 6 to 10 eggs in a shallow nest that they dig themselves.

The incubation period is among the longest of any reptile, lasting an exceptionally long 12 to 15 months, influenced by ambient temperatures. The hatchlings emerge fully developed and independent. Tuatara exhibit no parental care after the eggs are laid, and the offspring must survive on their own.

Studies have characterized their sperm (8) and also investigated male reproductive fitness and its relationship to immune stress (11). The slow pace of tuatara reproduction is mirrored by their exceptionally long lifespans. This longevity is one of the most important aspects of the species’ biology.

How Long Do Tuatara Live?

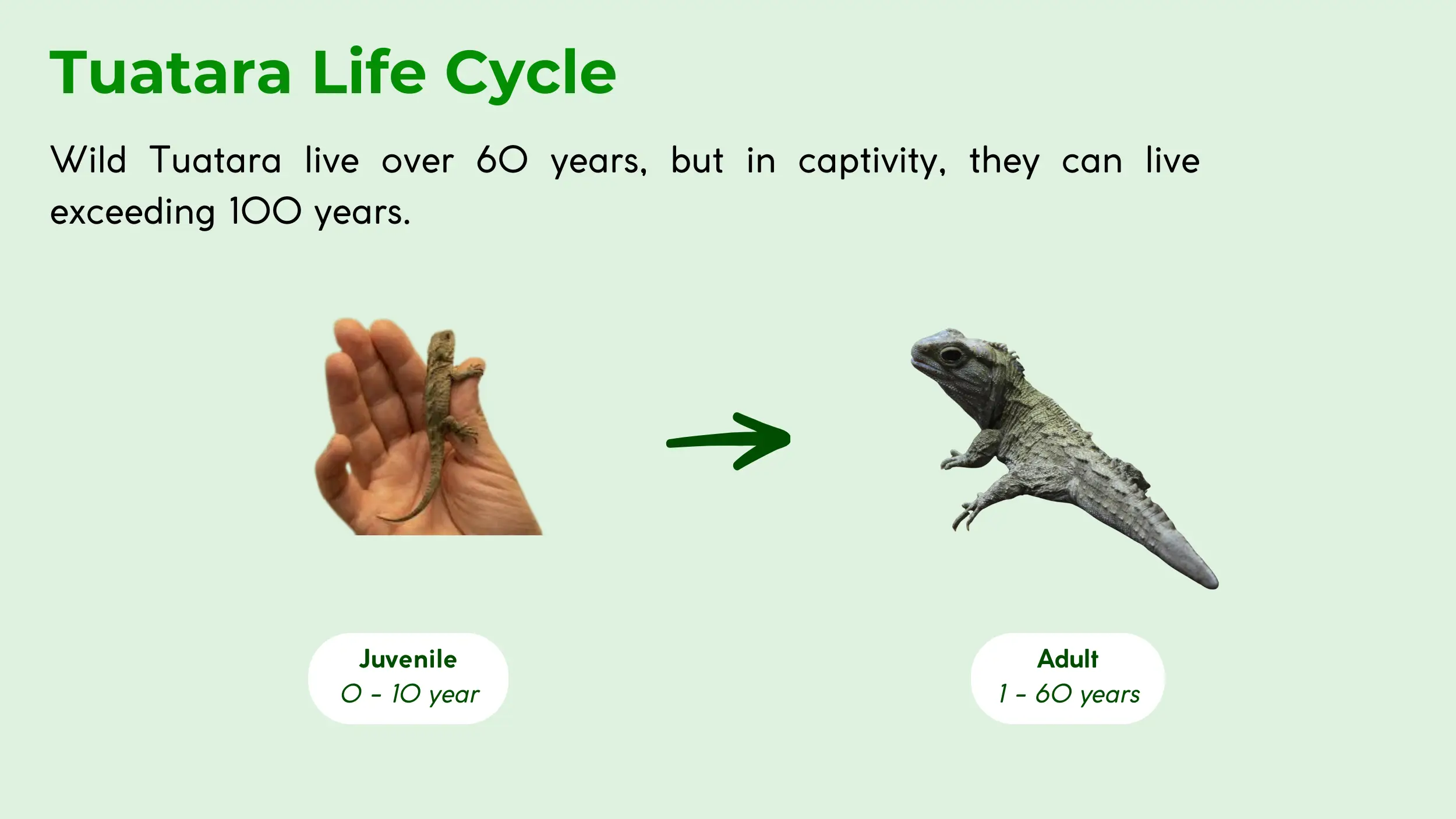

Tuatara live exceptionally long lives, with a life expectancy of over 60 years in the wild and a potential lifespan exceeding 100 years. Their extremely slow growth and maturation rates contribute to their longevity. They do not reach sexual maturity until they are 10 to 20 years old.

The oldest known tuatara in captivity, Henry, lived to be over 111 years old, a testament to the species’ endurance (12). Their longevity is attributed to a slow metabolism and an ability to thrive in cooler climates, factors that minimize cellular damage over time.

Despite their formidable appearance and ancient lineage, tuatara are not a threat to humans. In fact, they are a significant and beneficial species.

Are Tuatara Harmful/ Beneficial to Humans?

Tuatara are not harmful to humans and are considered a beneficial and culturally significant species. They are non-venomous and generally docile, posing no threat to people. When approached, their defensive behavior typically involves freezing or retreating into a burrow.

They are an important part of the ecosystem, especially in their island habitats, where they act as predators, helping control invertebrate populations. Their most profound benefit is their deep cultural significance to the Māori people, who consider them a taonga (special treasure) and a symbol of guardianship.

The tuatara is an ancient, sacred reptile, and its well-being is linked to the land and the Māori’s spiritual connection to nature. The modern history of the tuatara is a testament to dedicated conservation efforts. This success story has helped move them from the brink of extinction to a stable population.

Are Tuatara Endangered?

The tuatara’s conservation status is currently listed as Least Concern, but was described as “Rare” in a 1988 assessment, according to the IUCN Red List (5). This status reflects the success of intensive conservation efforts, which have secured their populations on offshore islands free of invasive predators. Historically, tuatara populations on mainland New Zealand were driven to extinction by rats and other introduced predators (13).

Their survival is a testament to modern conservation success. Since the early 1990s, the New Zealand government and conservation groups have actively managed predator-free islands and introduced tuatara to new, secure locations (1).

The species now has a stable population, with an estimated 100,000 individuals, but its survival remains tied to ongoing predator control and habitat protection efforts. The long history and survival of this species make it one of the most fascinating creatures on Earth. There are still many surprising facts to uncover about this living relic.

Frequently Asked Questions About Tuatara

Here are some of the most common questions and their definitive answers.

Are Tuataras Dinosaurs?

No, tuatara are not dinosaurs, but they are a distinct lineage of reptiles that coexisted with dinosaurs. They belong to a separate order, Rhynchocephalia, which diverged from the lineage of lizards and snakes approximately 240 million years ago.

How Are Tuataras Different From Other Reptiles?

Tuatara are different from other reptiles due to their unique anatomical features. They possess a parietal eye, a rigid skull with a fixed upper temporal arch, and a unique form of dentition. These ancient traits separate them from modern lizards and snakes.

Are Tuatara Dangerous?

Tuatara are not dangerous to humans. They are non-venomous and generally docile. When threatened, their primary defensive behavior is to retreat into their burrows. Human encounters with tuatara are rare and typically pose no risk.

Are Tuataras Good Pets?

No, tuatara do not make good pets. They are a highly protected species in New Zealand, and it is illegal to keep them as pets. Their specific dietary and environmental requirements are difficult to replicate, requiring specialized care.

Why Is Tuatara Not A Lizard?

Tuatara are not lizards because they belong to a separate reptile order, Rhynchocephalia. The key anatomical difference is in their skull. Tuatara have a rigid, unmoving quadrate bone, whereas lizards (order Squamata) have a flexible, hinged jaw.

Conclusion

The tuatara stands as a living testament to an ancient past, its unique biology and survival providing a window into the age of reptiles. At Animal Pedia, we are dedicated to providing scientifically accurate, visually engaging content to help you explore these incredible creatures. Continue your journey of discovery by exploring more of our comprehensive guides and articles on diverse animal life.