Reptiles (Class Reptilia) are a diverse group of cold-blooded, ectothermic, vertebrate animals characterized by breathing with lungs and possessing scaly skin [1]. This ancient lineage, comprising over 11,000 extant species, distinguishes itself from other animal classes through several key external features, notably the presence of epidermal scales or scutes that provide protection and prevent desiccation, a unique adaptation for terrestrial life [1, 2].

Unlike amphibians, reptiles typically lay amniotic eggs with leathery or calcareous shells, freeing them from aquatic environments for reproduction, a significant evolutionary advancement [1].

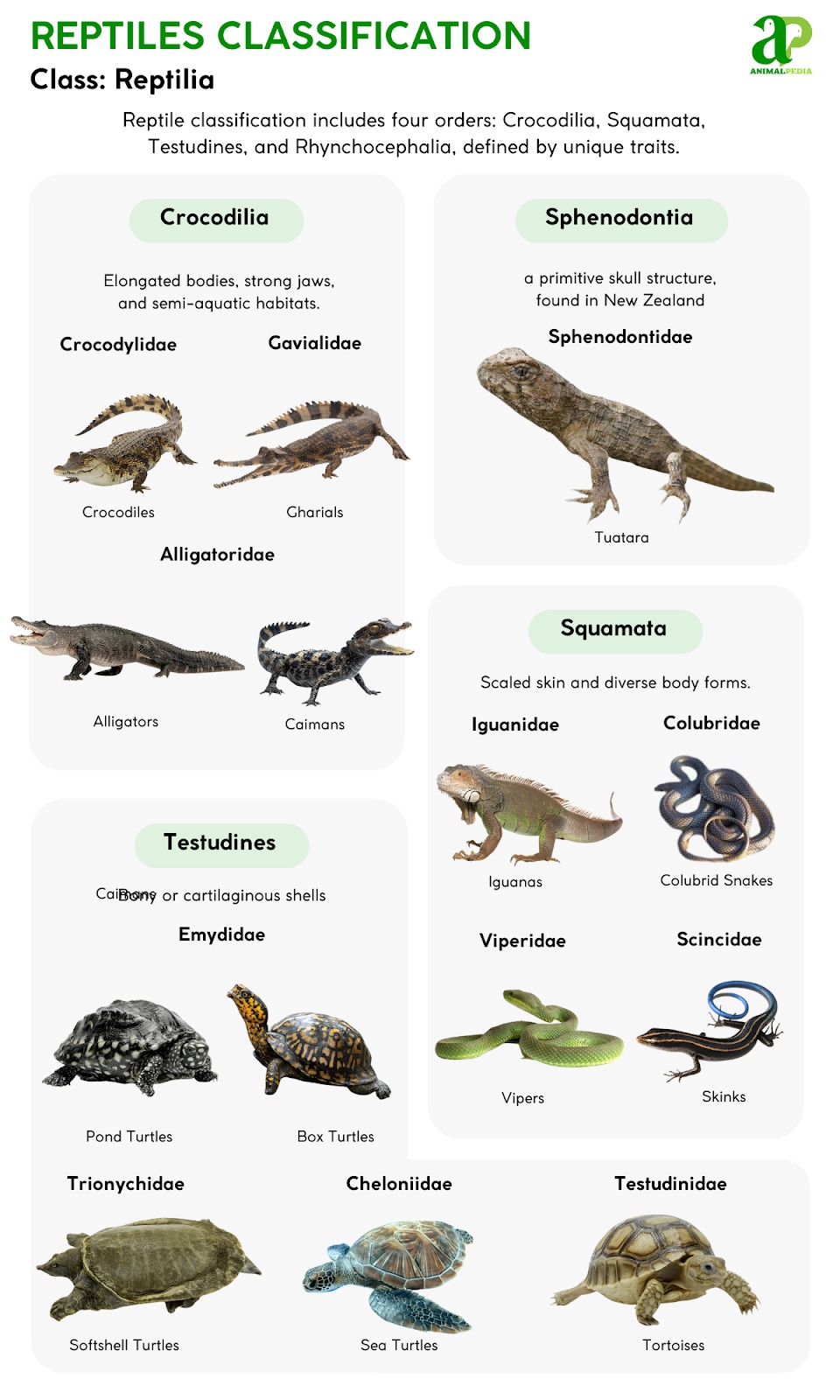

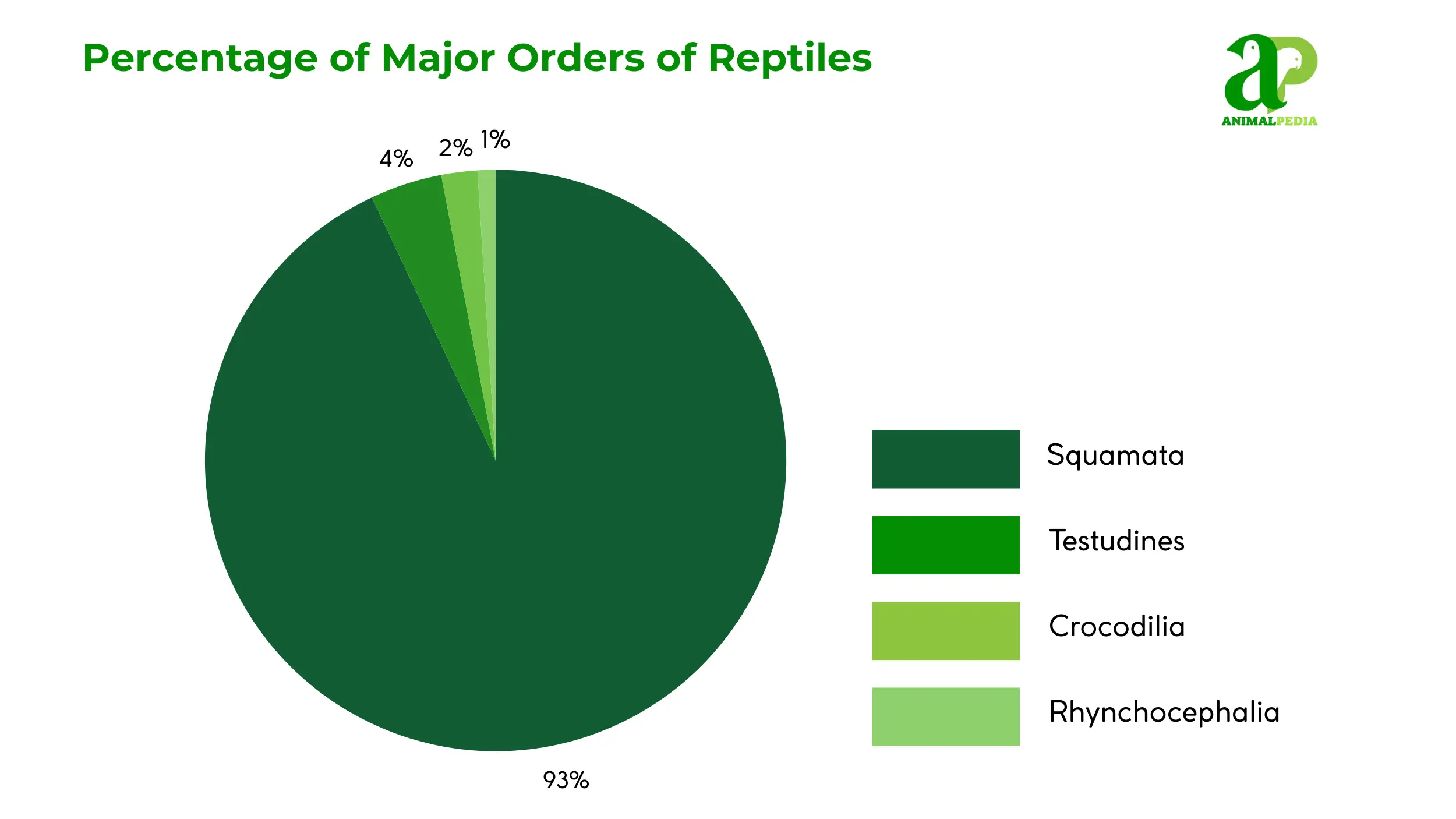

The class Reptilia is broadly divided into four main extant orders: Crocodilia (alligators, crocodiles, gharials, and caimans), Squamata (lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians), Testudines (turtles and tortoises), and Rhynchocephalia (tuataras) [3].

These animals exhibit a vast array of behavioral features, from the highly social dynamics of some crocodilians to the solitary hunting strategies of many snakes, and their reproductive methods vary from oviparity (egg-laying) to viviparity (live-bearing), playing crucial ecological roles as both predators and prey across diverse biomes [1]. This comprehensive guide will delve into the myriad species, distinctive characteristics, and fascinating facts that define this group.

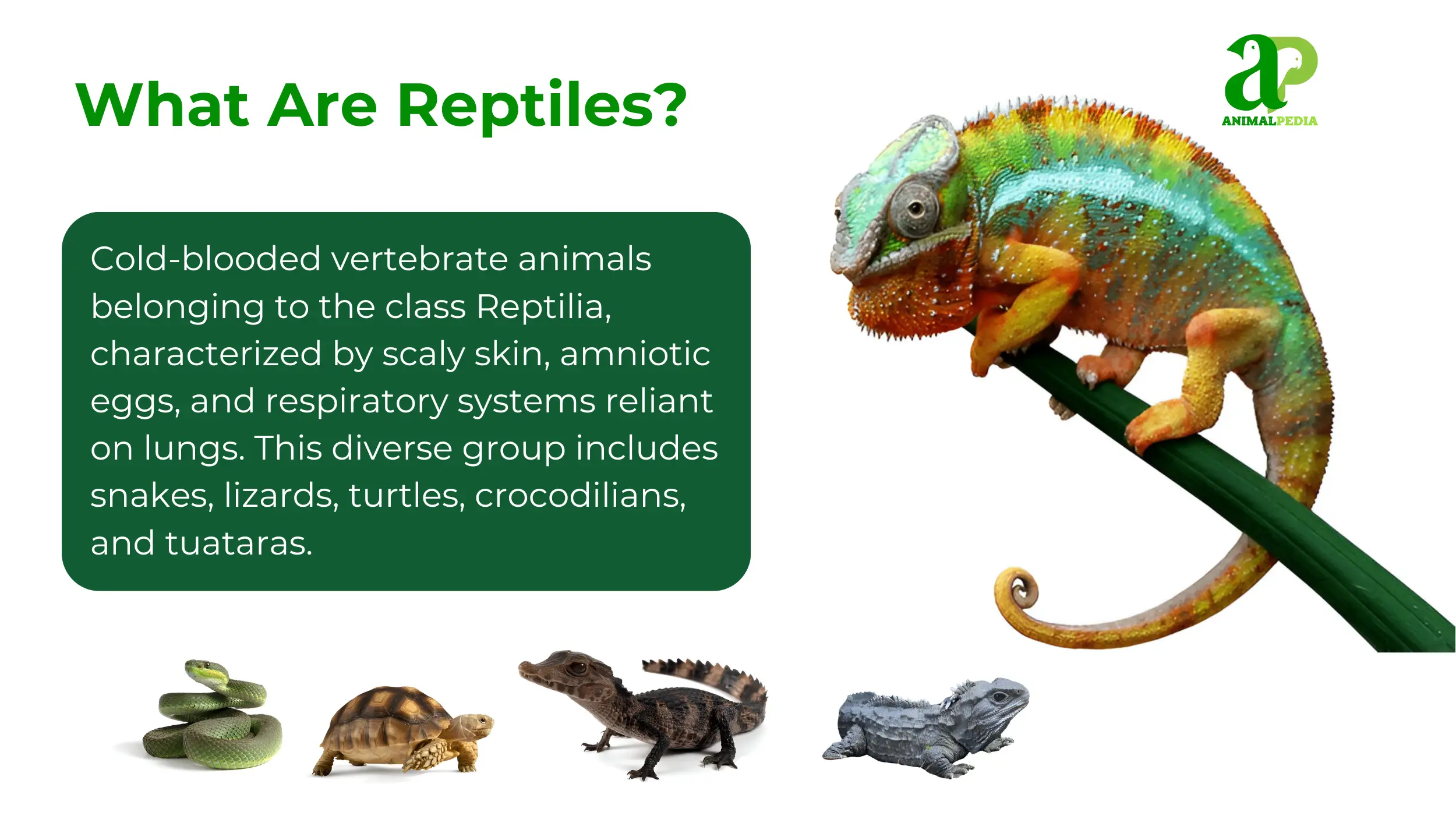

What are Reptiles?

Reptiles (Class Reptilia) are definitely cold-blooded vertebrates, characterized by lungs for respiration and skin covered in scales or scutes, a feature distinguishing them from other tetrapods [1]. This class, comprising over 11,000 species, is an amniote, meaning their embryos develop within a protective amniotic membrane, which enables them to lay eggs on land or give birth to live young without relying on water for reproduction —a critical adaptation for terrestrial existence [1, 2].

For instance, recent studies have highlighted the unique epidermal structure of reptilian skin, revealing its complex role in thermoregulation and defense, which significantly contributes to their adaptability across diverse environments [4].

While some might confuse reptiles with amphibians due to superficial similarities in appearance, the fundamental physiological differences in skin, reproduction, and respiratory systems delineate these distinct vertebrate groups [1].

Their geographic distribution is widespread, inhabiting every continent except Antarctica, thriving in ecosystems ranging from arid deserts and tropical rainforests to freshwater lakes and vast marine environments [3]. This pervasive presence is a testament to their evolutionary success and capacity for physiological adaptation.

Now that you know what reptiles are, let’s go beyond the basic definition. It’s time to dive into the incredible diversity of these creatures by exploring their main types.

What are the main types of Reptiles?

Reptiles Class Reptilia are classified into four primary orders: Squamata, Testudines, Crocodilia, and Rhynchocephalia, containing over 11,000 species worldwide as documented in global assessments (1).

- Squamata, which includes lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians, is the most successful group. With over 10,000 species, they make up about 93% of all living reptiles.

- Testudines is the order for turtles and tortoises. There are around 360 species, accounting for 4% of reptile diversity.

- Crocodilia includes alligators, crocodiles, caimans, and gharials. This group has 28 species, representing 2% of the total.

- Rhynchocephalia is a very special group, with only two surviving tuatara species. They are found exclusively in New Zealand.

The overwhelming dominance of the Squamata highlights their evolutionary success and adaptive radiation, allowing them to occupy nearly every terrestrial and many aquatic habitats globally. This broad classification provides a framework for understanding the incredible array of forms and functions within the reptilian lineage, leading us to a more detailed examination of each distinct order.

Order Squamata (Lizards and Snakes)

The Order Squamata, representing the most species-rich group within Class Reptilia, comprises over 10,000 species, accounting for approximately 93% of all extant reptiles globally [3, 5]. Squamates are characterized by their kinetic skulls, which allow for greater jaw mobility, particularly evident in snakes’ ability to consume prey larger than their heads [1]. Their primary physical traits include overlapping epidermal scales that are regularly shed. While most possess four limbs, snakes and some lizards exhibit limblessness, an evolutionary adaptation that enables specialized locomotion [1].

Squamates exhibit a global distribution, inhabiting virtually every terrestrial and many aquatic environments, from tropical rainforests to arid deserts [3]. Their behavioral repertoire is equally vast, encompassing a wide range of feeding strategies, from herbivory and insectivory to specialized predation, alongside diverse reproductive methods including oviparity and various forms of viviparity [1].

Ecologically, squamates play vital roles as both predators and prey, influencing insect and rodent populations, and serving as food sources for birds of prey and mammals, thereby maintaining delicate ecosystem balances [5].

Order Testudines (Turtles and Tortoises)

The Order Testudines comprises approximately 360 extant species, representing a distinct lineage within reptiles [3]. Their most defining physical characteristic is the bony shell, a unique structure formed by the fusion of vertebrae, ribs, and dermal ossifications [1]. This protective shell, divided into a dorsal carapace and a ventral plastron, offers formidable defense against predators [1].

Testudines are broadly categorized into two suborders based on neck retraction mechanisms: Cryptodira, which retract their necks by bending them vertically (e.g., most freshwater turtles and tortoises), and Pleurodira, which retract their necks sideways (e.g., side-necked turtles) [1].

Geographically, Testudines are widely distributed across terrestrial, freshwater, and marine environments globally, absent only from the extreme poles [3]. Their behaviors vary significantly; tortoises are primarily herbivorous terrestrial dwellers, while marine turtles are powerful swimmers migrating vast distances for foraging and breeding [1].

All species of Testudines are oviparous, laying eggs on land, even marine species [1]. Their ecological roles are diverse, ranging from maintaining aquatic plant populations to acting as significant seed dispersers in terrestrial ecosystems, thereby contributing to the health of habitats and biodiversity [5].

Order Crocodilia (Crocodilians)

The Order Crocodilia comprises 28 species of large, semi-aquatic reptiles, making it the smallest order by species count among extant reptiles, yet it is home to the largest living reptile — the Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus).

This order encompasses alligators, crocodiles, caimans, and gharials, all characterized by their robust, armored bodies covered in thick, scaly skin reinforced by bony osteoderms [1]. Crocodilians possess powerful jaws with numerous conical teeth, laterally compressed tails for propulsion in water, and specialized valved nostrils and ears that can close underwater [1].

Primarily found in tropical and subtropical regions across Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Americas, crocodilians inhabit a variety of freshwater and brackish environments, including rivers, lakes, swamps, and estuaries [3]. These apex predators are known for their ambush hunting techniques, patiently waiting to seize prey that ranges from fish and birds to large mammals [1].

Notably, crocodilians exhibit complex social behaviors, including parental care for their hatchlings and sophisticated vocalizations, a trait uncommon among reptiles [6]. Ecologically, they are crucial keystone species, shaping wetland ecosystems by creating and maintaining habitats and regulating prey populations [5].

Order Rhynchocephalia (Tuataras)

The Order Rhynchocephalia is the most exclusive among extant reptiles, comprising only two species within the single genus Sphenodon, commonly known as tuataras, both of which are endemic to a few offshore islands of New Zealand [3, 7]. These reptiles are characterized by their primitive characteristics, closely resembling their Triassic ancestors, making them a subject of intense evolutionary study [1].

Physically, tuataras possess a distinctive parietal eye (or “third eye”) on the top of their heads, which is sensitive to light and thought to play a role in circadian rhythms and hormone production, although it does not form images [1]. They also exhibit a unique dentition, with teeth fused directly to the jawbone, unlike the socketed teeth of most other reptiles [1].

Tuataras are predominantly nocturnal and insectivorous, though they also consume small vertebrates and seabird eggs [7]. Their extremely slow growth rate and longevity, with individuals living over 100 years, are significant biological features [7]. Reproduction is notably slow, with females laying clutches only every two to five years [7]. Ecologically, tuataras are vital components of their island ecosystems, sharing burrows with seabirds and acting as mesopredators (a predator that occupies a mid-ranking trophic level in a food web) [7].

Now that we’ve covered the main types of reptiles, you might be surprised to learn that within each category are many familiar examples, or the one you might already know!

Complete List and Examples of Reptiles

The following examples of reptiles are divided into three groups, including the common group, iconic examples, and the A-Z list of reptiles.

Commonly Encountered Examples

- Common Garter Snake (Thamnophis sirtalis): A slender North American serpent found in diverse habitats.

- Green Anole (Anolis carolinensis): A small, arboreal lizard of the southeastern United States known for its chameleon-like color changes.

- Leopard Gecko (Eublepharis macularius): A nocturnal lizard from arid regions of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India, widely kept as a pet.

Large and Iconic Examples

- Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus): The largest living reptile, found in coastal and estuarine environments across Southeast Asia and Australia.

- Komodo Dragon (Varanus komodoensis): The world’s heaviest lizard, native to a few Indonesian islands, an apex predator.

- Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas): One of the largest hard-shelled sea turtles, migrating across vast oceanic distances.

Specialized or Unique Habitats Examples

- Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus): A critically endangered fish-eating crocodilian characterized by a distinctively long, slender snout, found in the freshwater river systems of the Indian subcontinent.

- Marine Iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus): Unique to the Galápagos Islands, the only lizard that forages in the ocean, feeding on marine algae.

- Flying Dragon (Draco volans): A small, arboreal lizard from Southeast Asian rainforests that glides between trees using extended ribs and skin flaps.

A-Z Reference List (Examples from diverse families)

- African Spurred Tortoise (Centrochelys sulcata): Sahara Desert, Sahel; up to 80 cm, 90 kg.

- Ball Python (Python regius): West and Central Africa; up to 1.8 meters.

- Black Mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis): Sub-Saharan Africa; up to 4.3 meters, highly venomous.

- Burmese Python (Python bivittatus): Southeast Asia; up to 5.7 meters.

- Caiman Lizard (Dracaena guianensis): Amazon Basin; up to 1.2 meters, semi-aquatic.

- Chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus): Yemen, Saudi Arabia; up to 60 cm, arboreal.

- Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus): Southeastern and Central United States; up to 1.8 meters.

- Gila Monster (Heloderma suspectum): Southwestern United States, Mexico; up to 56 cm, venomous lizard.

- Green Tree Python (Morelia viridis): New Guinea, Australia; up to 2 meters, arboreal.

- King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah): Southeast Asia, India; up to 5.8 meters, the longest venomous snake.

- Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta): Atlantic, Pacific, Indian Oceans; up to 1.1 meters carapace length.

- Pancake Tortoise (Malacochersus tornieri): East Africa; up to 18 cm, flat shell.

- Rattlesnake (Crotalus spp.): Americas; various sizes, venomous.

- Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans): Central and Southern United States; up to 40 cm, freshwater turtle.

- Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus): Southeast Asia, Australia; up to 6+ meters.

- Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina): North America; up to 49 cm, freshwater.

- Tokay Gecko (Gekko gecko): Southeast Asia; up to 40 cm, vocal.

- Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus): New Zealand (islands); up to 80 cm.

- Veiled Chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus): Yemen, Saudi Arabia; up to 60 cm, arboreal.

- Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta scripta): Southeastern United States; up to 30 cm, freshwater turtle.

Although there are many species in the reptile class, as you see above, they still share some prominent characteristics. So, which are they, and how do they function in the reptile’s lifetime.

What are the key characteristics of Reptiles?

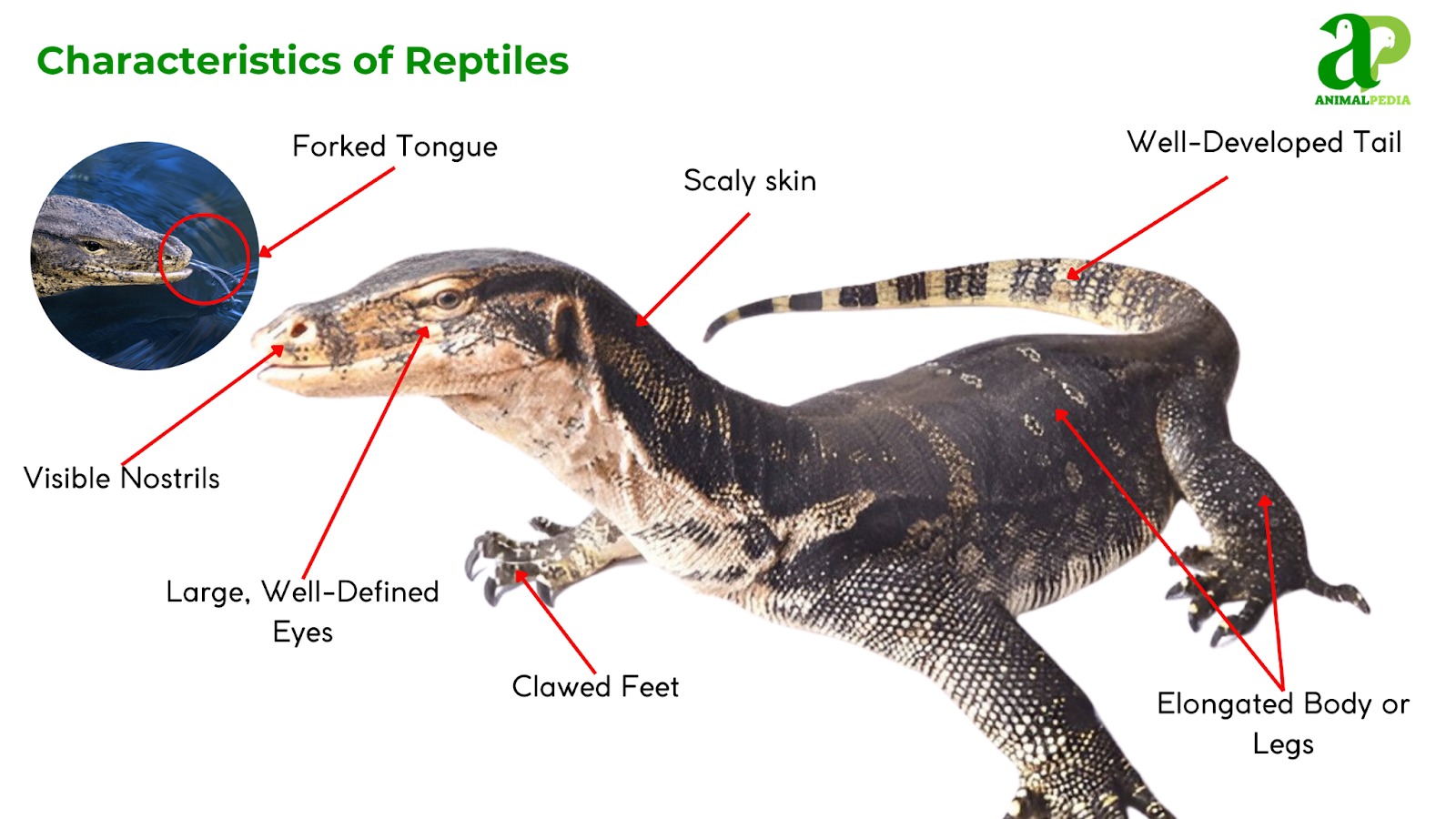

All Class Reptilia share four key characteristics that distinguish them from other animal groups: ectothermy, scaly skin, amniotic eggs, and lung respiration [1]. These fundamental traits have been pivotal to their success in diverse terrestrial and aquatic environments.

- Ectothermy (Cold-bloodedness): Reptiles are ectothermic, meaning they rely on external heat sources to regulate their body temperature, rather than generating significant internal heat like mammals and birds [1]. This adaptation allows them to thrive in environments with fluctuating temperatures, minimizing metabolic energy expenditure. For example, a study on desert reptiles demonstrated how behavioral thermoregulation, such as basking and seeking shade, is crucial for maintaining optimal body temperatures for metabolic processes [8].

- Scaly Skin: The skin of reptiles is covered in epidermal scales or scutes, composed of keratin, which provides protection against physical injury and, crucially, prevents water loss through evaporation [1, 4]. This epidermal covering is a significant adaptation for life on land, contrasting sharply with the moist, permeable skin of amphibians. Periodically, reptiles undergo ecdysis (shedding their skin) to allow for growth and to remove parasites [4].

- Amniotic Eggs: Reptiles are amniotes, meaning their embryos develop within an amniotic egg that contains a series of protective membranes and a yolk sac, providing nourishment and a self-contained aquatic environment [1]. This evolutionary innovation freed reptiles from the necessity of returning to water for reproduction, enabling them to colonize diverse terrestrial habitats [1]. Some species, like certain snakes and lizards, have further evolved viviparity (live birth), where eggs hatch internally [1, 5].

- Lung Respiration: All reptiles, without exception, breathe using lungs throughout their life cycle [1]. Unlike amphibians, which may use gills or skin for respiration, even aquatic reptiles like marine turtles and crocodiles depend on pulmonary respiration for oxygen intake [1]. This reliance on lungs is directly tied to their terrestrial independence and efficient oxygen uptake.

Every feature we’ve just explored plays a crucial role in the survival and development of the Reptiles. But how did they develop such extraordinary adaptations? The answer lies in their fascinating evolutionary journey.

How did Reptiles evolve?

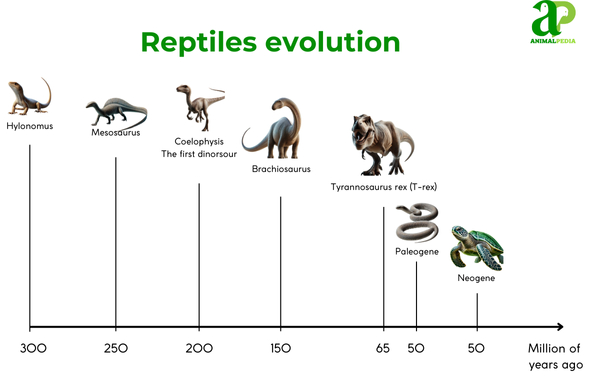

Reptiles first appeared during the Carboniferous period, approximately 320 million years ago, evolving from early amniote ancestors that diverged from amphibians [1, 10].

This critical evolutionary transition involved the development of the amniotic egg, a pivotal innovation that enabled reproduction to occur entirely on land, eliminating the need for aquatic larval stages. Early reptiles, known as anapsids (characterized by skulls without temporal fenestrae), gave rise to various lineages, including the ancestors of modern turtles [1].

However, it was the divergence into diapsids (possessing two temporal fenestrae in their skulls) that led to the vast majority of extant reptiles, including the Lepidosauromorpha (lizards, snakes, and tuataras) and Archosauromorpha (crocodilians and, notably, birds, which are now considered avian reptiles) [1, 11].

The Mesozoic Era, often referred to as the “Age of Reptiles,” witnessed significant adaptive radiations of various reptilian groups, including the dominance of dinosaurs, marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs, and flying pterosaurs [1]. While many of these ancient lineages became extinct, the evolutionary trajectories established during this period paved the way for modern reptilian diversity.

Where Do Reptiles Live?

Reptiles are found across nearly all continents, excluding Antarctica, exhibiting an extraordinary global distribution that underscores their adaptability [3]. Their habitats span a vast spectrum, from scorching deserts to lush tropical rainforests, temperate forests, expansive grasslands, and diverse wetland and freshwater environments [1].

Furthermore, several lineages, notably sea turtles and some sea snakes, are fully adapted to marine environments, inhabiting oceans worldwide [1].

The distribution of reptiles is heavily influenced by their ectothermic physiology, necessitating environments with suitable temperature regimes for thermoregulation [1]. Consequently, diversity is highest in tropical and subtropical regions near the equator, where consistent warmth allows for year-round activity and greater metabolic efficiency.

As latitude and altitude increase, reptilian diversity generally declines due to cooler temperatures and shorter active seasons [5]. However, specialized adaptations allow some species to inhabit cooler temperate zones, such as the common garter snake found in parts of Canada or certain lizards in high-altitude deserts. These habitat specializations, from burrowing in arid soils to arboreal life in canopies, exemplify their evolutionary success.

Living in various habitats, reptiles have developed a wide range of behaviors that make them incredibly diverse and successful survivors. Some even exhibit surprising social behaviors, challenging common perceptions.

How do Reptiles Behave?

Reptiles exhibit a wide array of behaviors crucial for their survival and adaptation across diverse environments. Their actions are primarily centered around obtaining food, reproducing, moving efficiently, and interacting with their surroundings for communication and defense.

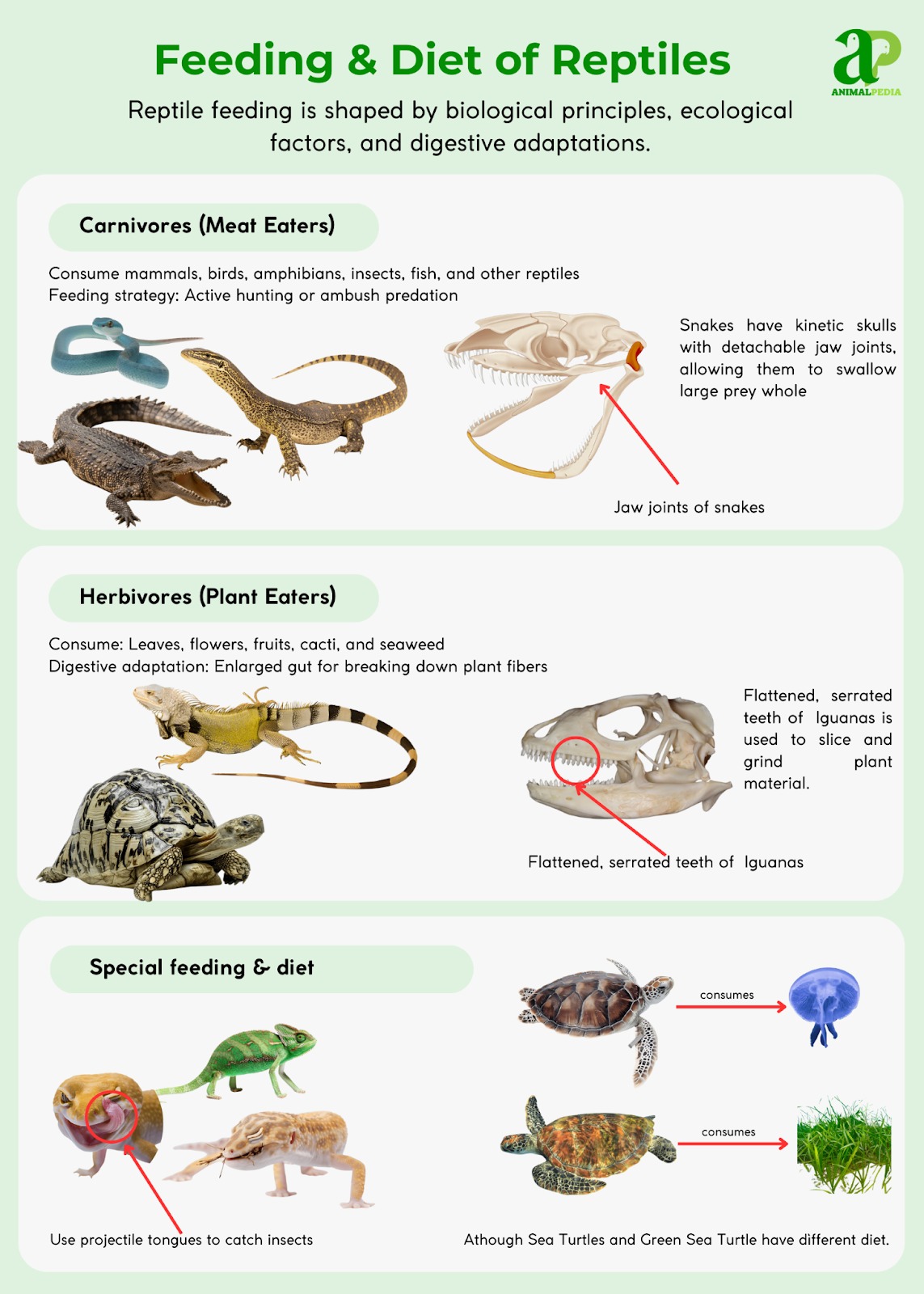

- Diet and Feeding Strategies: Reptiles have diverse diets (carnivores, herbivores, omnivores) and varied feeding strategies like ambush predation, active hunting, or grazing, supported by specialized adaptations.

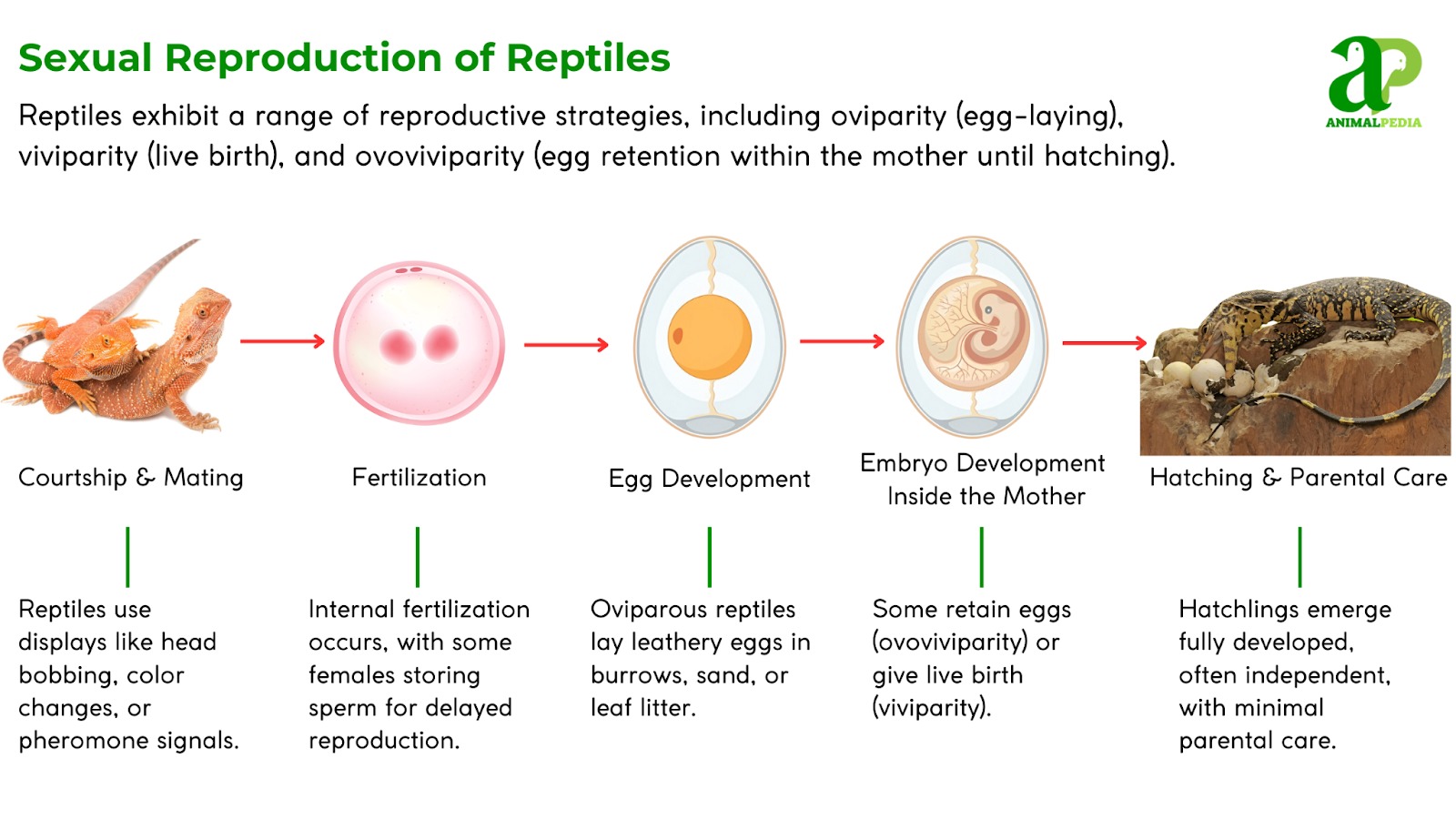

- Reproduction and Development: Reptiles employ diverse reproductive methods (oviparous, viviparous, and ovoviviparous) with unique mating behaviors and varying levels of parental care to optimize survival.

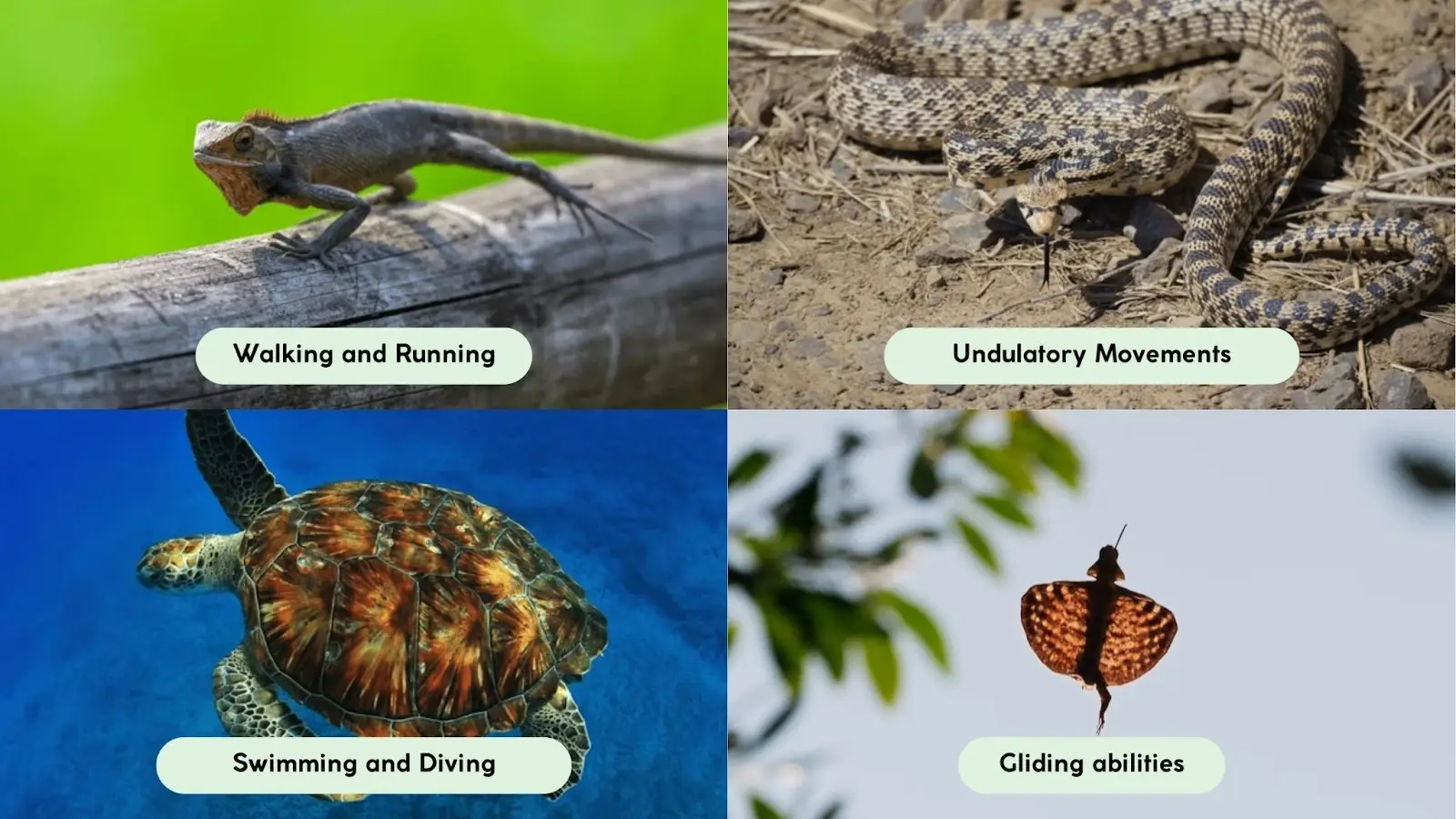

- Movement and Locomotion: Reptiles exhibit varied locomotion, from lizards’ agile gaits to sea turtles’ swimming and unique strategies like sidewinding, all adapted for their environment.

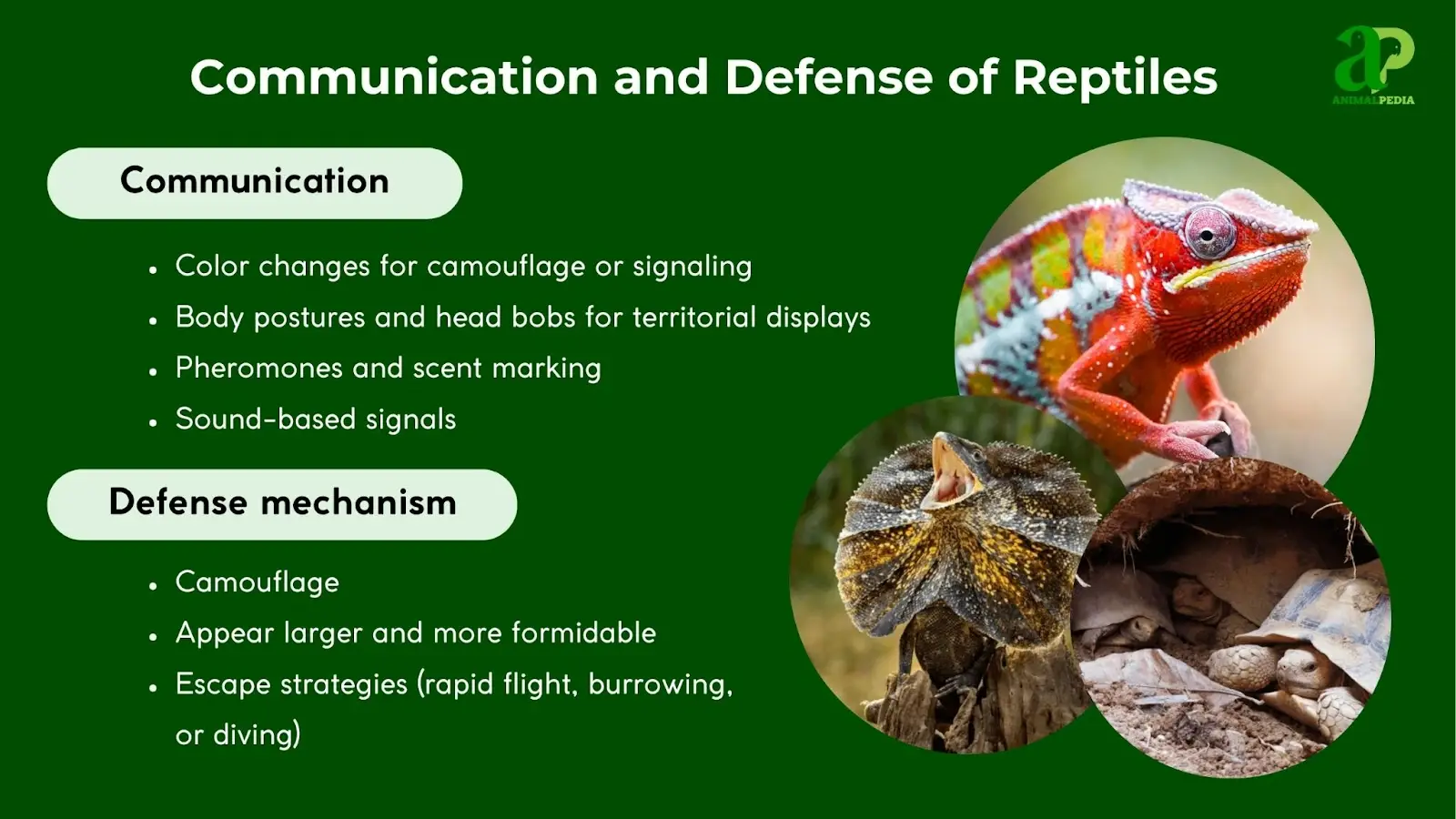

- Communication and Defense: Reptiles use visual (color, posture) and chemical communication (pheromones). Their defensive behaviors include camouflage, threat displays, and physical defenses, such as shells.

These survival-focused behaviors are tied to ectothermy, with basking regulating feeding and movement [15]. Unlike warm-blooded animals, reptiles conserve energy, aligning activities with environmental conditions, ensuring efficiency in predation, mating, and defense across diverse ecosystems.

Diet and Feeding Strategies

The diets of reptiles range from carnivory to herbivory and include opportunistic omnivory [1]. Most of them are carnivores, preying on insects, other invertebrates, fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals, while some species, such as tortoises and certain iguanas, are primarily herbivorous, consuming plant matter [1, 5]. A smaller number, including certain freshwater turtles, exhibit omnivorous diets, feeding on both plants and animals [1].

Reptiles employ varied feeding strategies, from the explosive ambush predation characteristic of many snakes and crocodilians, which rely on stealth and sudden attacks to subdue prey, to the more active foraging observed in many lizards [1].

Anatomical adaptations are crucial; snakes possess specialized hinged jaws and, in venomous species, fangs for delivering toxins [5]. Crocodilians utilize powerful jaws and conical teeth for crushing and gripping, while herbivorous tortoises have blunt, grinding surfaces on their jaws for processing vegetation [1].

Reproduction and Development

Reptile reproductive methods display significant variation, encompassing oviparity (egg-laying), viviparity (live birth), and ovoviviparity (eggs hatching internally before live birth) [1, 5]. The majority of reptiles are oviparous, laying their amniotic eggs in nests on land, often in concealed locations to protect them from predators and environmental fluctuations.

Conversely, viviparous and ovoviviparous species, primarily found among certain lizards and snakes, provide greater protection and thermal stability for their developing offspring within the maternal body [1]. Mating behaviors often involve elaborate courtship rituals and territorial displays, with males showcasing size, coloration, or physical prowess to attract mates and deter rivals [5].

Following successful mating, the life cycle progresses from egg development or internal gestation, through hatching (or birth), to juvenile growth [1]. The incubation period for eggs can vary widely, from weeks to months, often influenced by environmental temperature, which in many species, particularly turtles and crocodilians, determines the sex of the offspring (temperature-dependent sex determination) [12].

While most reptiles exhibit limited or no parental care after egg-laying or birth, notable exceptions exist, such as crocodilians, which may guard nests and protect hatchlings for extended periods [6]. Seasonal breeding patterns are common, typically triggered by environmental cues like temperature changes, rainfall, or photoperiod, ensuring offspring are born during optimal conditions for survival [5].

Movement and Locomotion

Reptiles exhibit a diverse array of movement and locomotion strategies, intricately linked to their varied body structures and habitats. Terrestrial locomotion includes the familiar walking and running of lizards and crocodilians, utilizing sprawling limbs that generate propulsion [1].

Snakes, lacking limbs, employ various undulatory movements such as serpentine locomotion, rectilinear movement, and specialized sidewinding in sandy environments, each adapted for efficiency on specific substrates [13]. Many arboreal species, like chameleons, demonstrate climbing abilities with prehensile tails and specialized feet [1].

In aquatic environments, reptiles display impressive adaptations for swimming and diving. Sea turtles, for example, possess highly modified flippers that enable powerful propulsion through water, while crocodilians utilize their muscular, laterally compressed tails for efficient aquatic movement [1].

Some species, such as the flying dragon (Draco volans), have evolved unique gliding abilities, utilizing extended ribs and skin membranes to traverse canopy gaps [1]. These diverse forms of locomotion underscore the evolutionary plasticity of reptiles, allowing them to exploit a vast range of ecological niches across terrestrial, arboreal, and aquatic realms.

Communication and Defense

Reptiles utilize a fascinating array of communication methods and defensive strategies to navigate their environments, interact with conspecifics, and evade predators. Visual communication is prominent, with species displaying vibrant color changes for camouflage or signaling, as seen in chameleons, or engaging in elaborate body postures and head bobs for territorial displays and courtship, common among many lizards [1, 14].

Chemical communication, primarily through pheromones and scent marking using glands or cloacal secretions, plays a crucial role in mate attraction, territorial demarcation, and individual identification, particularly in snakes and certain lizards [5]. While generally less vocal than other vertebrates, some reptiles produce sound-based signals, such as the distinctive hissing of snakes, which serves as a warning, or the complex vocalizations of crocodilians used for social cohesion and parental communication [6].

When threatened, reptiles employ a diverse range of defensive behaviors and physical adaptations. Camouflage is a primary defense, allowing many species to blend seamlessly with their surroundings, rendering them virtually invisible to predators [1]. If detected, many will engage in threat displays, such as the cobra’s hood expansion or a frilled-neck lizard’s intimidation display, to appear larger and more formidable [5].

Escape strategies include rapid flight, burrowing, or diving into water. Physical defenses range from the formidable bony shells of turtles and tortoises to the sharp claws and powerful bites of crocodilians, and the venom delivery systems of certain snakes, which serve both for predation and self-defense [1, 5].

So, we’ve explored what makes reptiles tick when it comes to their actions. But believe it or not, there’s even more to learn! Let’s explore some fascinating facts about them that may surprise you.

How Do Humans Interact With Reptiles?

Reptiles interact with humans in two main ways: through the pet trade, where captivating species like bearded dragons are popular companions, and via commercial uses, such as the demand for crocodile leather in the fashion industry.

These relationships underscore the cultural and economic significance of reptiles. The following sections examine the appeal of the pet trade and its associated care demands, as well as commercial applications, highlighting ethical considerations and conservation impacts [13, 11].

Reptiles as Pets and in Captivity

The ownership of reptiles as pets has seen a significant rise in popularity, driven by their unique characteristics, relatively low maintenance compared to some mammalian pets, and fascinating behaviors [23]. Species such as the Leopard Gecko (Eublepharis macularius), Bearded Dragon (Pogona vitticeps), and Ball Python (Python regius) consistently rank among the most favored due to their manageable size, docile temperaments, and diverse captive-bred morphs [24].

Beyond private ownership, reptiles play vital educational roles in zoos, wildlife centers, and nature conservancies. These institutions offer invaluable opportunities for public engagement, fostering appreciation for reptilian diversity and promoting conservation efforts by showcasing their biological significance and unique adaptations [25].

The popularity of reptiles in herpetoculture reflects human fascination with their diversity and adaptability.

Are Reptiles Endangered and How Can We Protect Them?

Unfortunately, yes, a significant number of reptile species are currently threatened with extinction. A comprehensive assessment published in 2022 on The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ revealed that at least 21% of all reptile species globally are at risk of extinction, classified as Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered [1, 2].

The primary threats driving these declines include pervasive habitat loss due to agriculture, deforestation, and urban development, the pervasive impacts of climate change, and the persistent threat of illegal wildlife trade for pets, leather, and traditional medicine [2, 31].

Despite these alarming statistics, notable conservation success stories are emerging. The American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), once severely endangered, has made a comeback due to robust conservation efforts and was delisted from the U.S.

Endangered Species Act just 20 years after its initial listing [32]. Similarly, the Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei) and the Christmas Island Blue-tailed Skink (Cryptoblepharus egeriae) have seen recovery through intensive captive breeding and invasive species control programs [33].

Individuals can contribute by supporting reputable conservation organizations, avoiding the purchase of wild-caught reptiles, advocating for habitat protection, and promoting responsible pet ownership. Protecting reptiles is crucial as they are keystone species in many ecosystems, regulating pest populations, dispersing seeds, and serving as vital links in food webs [34, 35].

Frequently Asked Questions About Reptiles

Interested in learning about reptiles? Let’s address some common questions!

Do All Reptiles Lay Eggs?

No, not all reptiles lay eggs. While the majority of reptile species are oviparous (egg-laying), some species, particularly certain snakes and lizards, are viviparous (live-bearing) or ovoviviparous (eggs hatch internally) [1, 5]. This adaptation allows for greater protection of offspring in diverse environments.

Are All Reptiles Dangerous to Humans?

No, the vast majority of reptiles are not dangerous to humans. While some species possess venom or powerful bites, most reptiles are shy and pose no threat unless provoked [1, 5]. Incidents are rare and often result from mishandling or accidental encounters in their natural habitats.

Do All Reptiles Have Scales?

Yes, all reptiles possess scales or scutes covering their skin. These epidermal structures, made of keratin, are a defining characteristic of the class Reptilia [1, 4]. They provide essential protection against physical injury and desiccation, enabling reptiles to thrive in terrestrial environments.

Do Reptiles Have Backbones?

Yes, all reptiles have backbones. Reptiles are vertebrates, meaning they possess a vertebral column, or backbone, which is a fundamental characteristic of this subphylum [1]. This internal skeletal structure provides support and protection for the spinal cord.

Which Reptile Makes the Best Pet for Beginners?

For beginners, the Leopard Gecko (Eublepharis macularius) or Bearded Dragon (Pogona vitticeps) is often recommended as an ideal reptile pet. They are relatively docile, manageable in size, and have well-understood husbandry requirements, making them easier to care for than many other species [24].

What’s The Difference Between Reptiles and Amphibians?

The primary difference lies in their skin, reproduction, and respiration. Reptiles have dry, scaly skin, lay amniotic eggs on land, and breathe with lungs throughout their lives [1]. Amphibians, conversely, typically have moist, permeable skin, lay non-amniotic eggs in water, and often undergo metamorphosis with larval stages that include gills [1].

Why Are Reptiles Cold-Blooded?

Reptiles are considered “cold-blooded” or ectothermic because they rely on external heat sources, such as sunlight, to regulate their body temperature [1, 9]. This metabolic strategy conserves energy, allowing them to thrive in environments with fluctuating temperatures and subsist on less frequent meals compared to warm-blooded animals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, reptiles represent an incredibly diverse and ancient lineage of vertebrates, uniquely adapted to thrive across nearly every corner of our planet. From their defining ectothermy and scaly skin to the evolutionary marvel of the amniotic egg, these creatures exhibit an array of characteristics, behaviors, and ecological roles.

While facing significant conservation challenges, ongoing efforts and responsible human actions are crucial for safeguarding their future. Understanding and appreciating reptiles is essential not only for their intrinsic value but also for recognizing their vital contributions to the health and balance of global ecosystems.