Crocodilia is an ancient order of large, predatory reptiles that includes crocodiles, alligators, caimans, and gharials. With 27 living species, crocodilians have survived for over 200 million years, making them contemporary with dinosaurs and one of the most successful animal groups in evolutionary history. These formidable predators range in size from the dwarf crocodile at 4.9 ft (1.5 meters) to the massive saltwater crocodile reaching lengths of up to 20.2 ft (6.17 meters). The scientific study of crocodilians, part of herpetology, reveals their adaptations and complex behaviors.

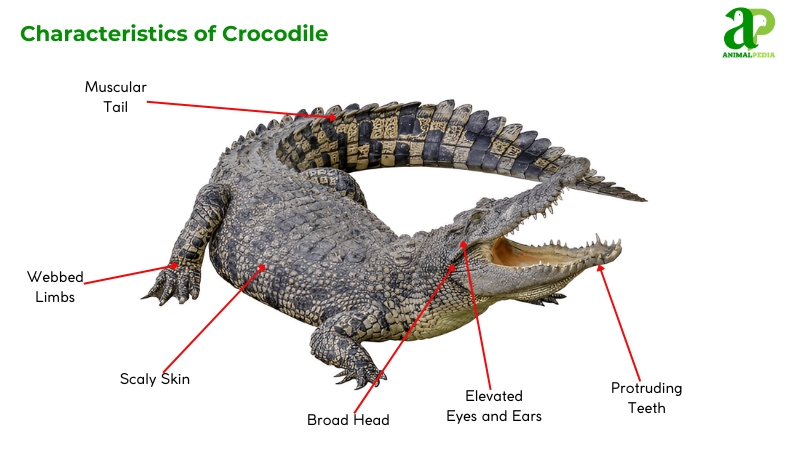

Crocodilians are characterized by several distinctive features, including heavily armored bodies covered in osteoderms, powerful jaws with conical teeth, and a specialized “secondary palate” that allows breathing while partially submerged. They possess sophisticated sensory adaptations, including pressure-sensitive organs on their scales, excellent night vision, and complex hearing mechanisms. As members of Archosauria, they share a closer evolutionary relationship with birds than with other living reptiles.

The evolutionary history of Crocodilia extends back to the Late Cretaceous period, though their ancestors, the Crocodylomorpha, first appeared in the Late Triassic around 225 million years ago. During their evolution, crocodilians have developed aquatic adaptations while retaining features of their terrestrial ancestors. Ancient crocodilians exhibited greater diversity in form and lifestyle, including fully marine species and terrestrial hunters, before settling into their current semi-aquatic niche.

Crocodilians display sophisticated behaviors and adaptations that belie their primitive appearance. They exhibit complex social structures, including hierarchical relationships and elaborate courtship rituals. Their parental care is among the most developed in the reptile world, with mothers guarding nests and protecting hatchlings. These reptiles also show intelligence, capable of tool use and cooperative hunting strategies.

Today, crocodilians are apex predators in their ecosystems, playing crucial roles in maintaining aquatic and riparian habitat balance. They demonstrate extraordinary physiological capabilities, including efficient heart structure, powerful immune systems, and the ability to survive long periods without food. Their unique combination of primitive and advanced traits makes them fascinating subjects for scientific research.

In this comprehensive article, we’ll explore the captivating world of Crocodilia, examining their diverse characteristics, evolutionary heritage, and ecological importance. From their sophisticated hunting strategies to their complex social behaviors, we’ll investigate what makes these ancient reptiles one of nature’s most successful survivors and how they maintain their position as dominant predators in modern ecosystems.

What are Crocodilia’s characteristics?

Crocodilia has 3 features as follows:

- The size range is 10–13 feet (3–4 meters ) in length and weighs around 660–1,100 lbs (300–500 kg).

- Skin features keratinized scales, collagen-rich dermis, bony osteoderms, and ISOs for protection, flexibility, and sensory detection.

- Teeth are conical, continuously replaced, highly mineralized, interlocking, and specialized for gripping prey and executing the “death roll.”

Size

Crocodilians are among the largest and heaviest of present-day reptiles. On average, an adult crocodile typically measures 3–4 meters (10–13 feet) in length and weighs around 300–500 kg (660–1,100 lbs).

However, this number can vary depending on the species and habitat.

The heaviest Crocodilia is the saltwater crocodile, weighing 2,400 pounds (about 1,075 kg). In particular, the Nile Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) of Africa and some saltwater crocodiles in Southeast Asia and Australia can reach up to 7 meters long and weigh nearly 2,650 pounds (more than 1,200 kg).

On the contrary, the smallest Crocodilians were the smooth-fronted caiman (Paleosuchus) and the dwarf species (Osteolaemus tetraspis), whose length is about 1.7 meters.

Skin

Crocodile skin consists of three specialized layers providing protection and sensory capabilities. This intricate system comprises multiple specialized layers that work together to form an exceptionally durable and functional integument.

- The epidermis, the outermost layer, is composed primarily of keratinized cells that provide essential water resistance and protection. High concentrations of keratin in the epidermis layers form tough protective scales. The dermis features abundant Type I and III collagen, providing crucial structural support and elasticity. Additionally, lipids and glycoproteins help maintain optimal skin hydration and flexibility.

- The thicker layer is rich in collagen fibers and connective tissues that give the skin its renowned strength and elasticity.

- Embedded within the dermis are osteoderms, or bony scutes – calcified plates that offer additional protection against predators, UV radiation, and physical injuries.

The presence of Integumentary Sensory Organs (ISOs) is one of the most fascinating features of crocodile skin. These organs function as highly sensitive pressure receptors, allowing crocodiles to detect water movement, vibrations, and locate prey even in complete darkness.

The skin’s adaptations include sophisticated camouflage through variable pigmentation, effective waterproofing through specialized scales and oil-producing glands, and robust UV protection via thick, keratinized scales. These features make crocodile skin one of the most well-adapted reptilian integuments for survival in diverse environments.

Teeth

Each crocodile possesses 60-70 conical, sharp teeth set in individual sockets within the jaw—a configuration known as the codont dentition. Throughout their lifetime, crocodiles can replace each tooth 50-70 times, with younger individuals replacing teeth more frequently than older ones. This ensures they maintain sharp, functional teeth despite the considerable wear from their aggressive feeding habits.

This is called polyphyodonty, the ability of certain animals to continuously replace lost or damaged teeth throughout their lifetimes, ensuring they always have functional teeth for feeding.

The teeth consist of an outer enamel layer and an inner dentine core, similar to human teeth but with substantially higher mineralization. This composition results in exceptional hardness and wear resistance, essential for their predatory lifestyle. When the jaw closes, the upper and lower teeth interlock precisely, creating an incredibly secure grip on prey.

Crocodile teeth are specifically adapted for their hunting strategy, focusing on gripping and holding rather than chewing. This adaptation works in concert with their infamous “death roll”—a powerful spinning maneuver used to tear apart large prey. This dental system produces the strongest recorded bite force of any animal, ranging from 3,700 to 5,000 pounds per square inch.

Which is the exception of Crocodile?

The False Gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii) and African Dwarf Crocodile (Osteolaemus tetraspis) represent fascinating exceptions to typical crocodilian patterns, showcasing the diverse adaptations within this ancient family.

- False Gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii)

Despite its gharial-like appearance with a long, narrow snout adapted for fishing, genetic analysis firmly places it within the Crocodylidae family. While initially thought to be a specialized fish-eater like the true gharial, recent research reveals a broader diet including large mammals such as monkeys and deer. Unlike their more aggressive relatives, False Gharials are secretive and rarely engage in territorial conflicts with humans.

- African Dwarf Crocodile (Osteolaemus tetraspis)

At just 1.5-1.9 meters in length, the African Dwarf Crocodile is notably smaller than most crocodiles that reach 3-6 meters. Its lifestyle also differs significantly, favoring a semi-terrestrial existence with nocturnal habits and extensive burrow use. Their diet consists primarily of smaller prey like insects, crustaceans, and small vertebrates, contrasting sharply with the large-prey hunting strategy of typical crocodiles.

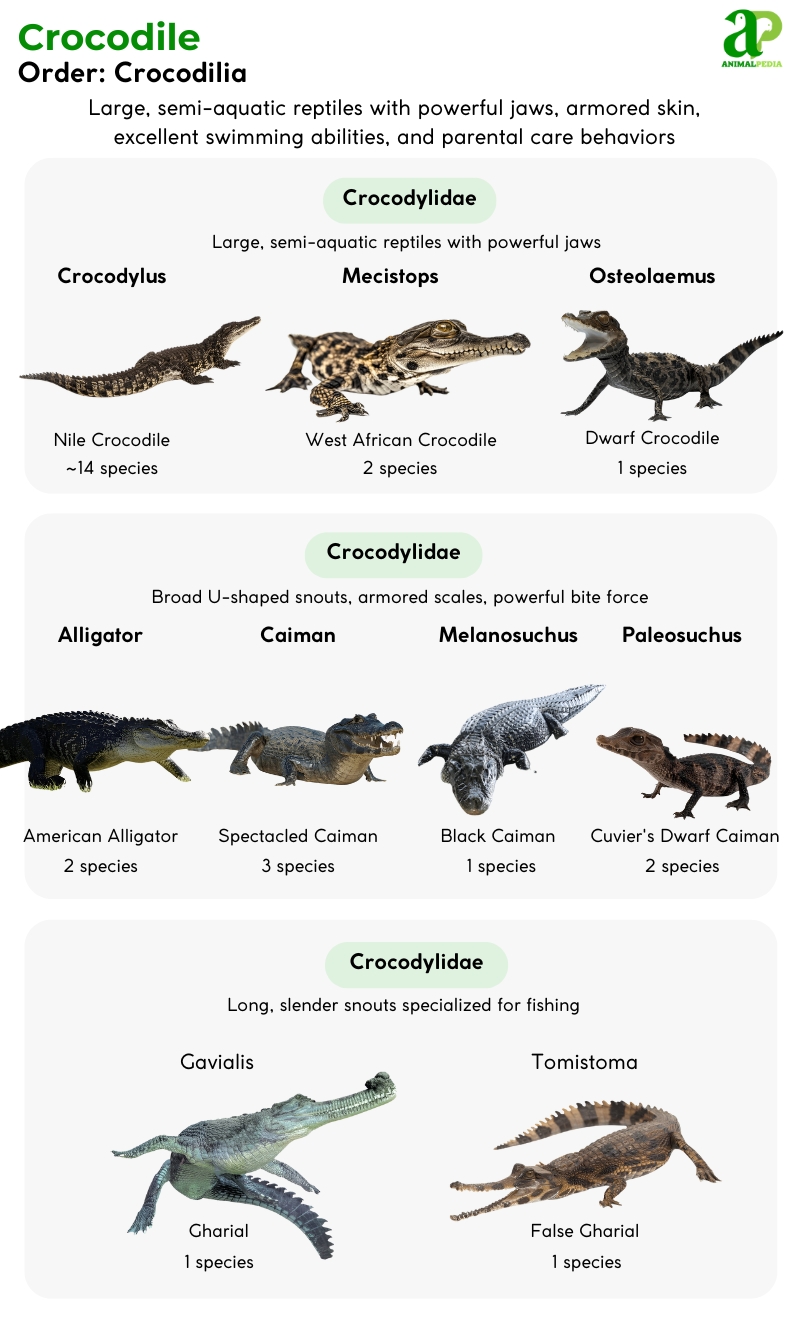

How is Crocodilia classified?

Crocodiles are classified based on morphological traits, genetic analysis, and evolutionary history. These principles distinguish Crocodiles into three families. Morphologically, snout shape, dental structure, and salt gland functionality distinguish the three families: Gavialidae, Alligatoridae, and Crocodylidae.

- Family Crocodylidae: The first is Crocodylidae, which includes true crocodiles. These reptiles are typically found in freshwater and saltwater environments such as rivers, lakes, and coastal areas. They are characterized by a V-shaped snout, powerful jaws, and a robust body. Crocodiles are primarily ambush predators, often waiting for prey to approach the water’s edge.

- Family Alligatoridae: The second family is Alligatoridae, which encompasses alligators and caimans. Alligators have a U-shaped snout that is broader than that of crocodiles and are primarily found in freshwater environments such as swamps, marshes, and rivers. They are known for their vocalizations and social behavior, particularly during the breeding season.

- Family Gavialidae: The third family is Gavialidae, which includes gharials and false gharials. Gharials are characterized by their long, narrow snouts, which are adapted for catching fish. They primarily inhabit river systems in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia and are specialized fish-eaters, using their elongated jaws to snatch prey from the water.

Here is the classified diagram with the specific number of species for each family.

Crocodilia: ~27 species

├── Family: Crocodylidae

│ ├── Genus: Crocodylus: ~14 species

│ ├── Genus: Mecistops: 2 species

│ └── Genus: Osteolaemus: 1 species

├── Family: Alligatoridae

│ ├── Sub-family: Alligatorinae

│ │ ├── Genus: Alligator: 2 species

│ ├── Sub-family: Caimaninae

│ │ ├── Genus: Caiman: 3 species

│ │ ├── Genus: Melanosuchus: 1 species

│ │ └── Genus: Paleosuchus: 2 species

├── Family: Gavialidae

├── Genus: Gavialis: 1 species

└── Genus: Tomistoma: 1 species

Where do Crocodilians live?

Crocodilians are amphibious reptiles that thrive in both aquatic and terrestrial environments. They inhabit diverse water bodies, including rivers, lakes, wetlands, swamps, estuaries, and mangrove forests. On land, they utilize forests, savannas, grasslands, and even deserts for basking, nesting, and regulating body temperature. Besides, Crocodilians inhabit tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, with distinct distribution patterns across families and species.

In terms of distribution, Crocodiles demonstrate the widest geographic range, including the Indo-Pacific region from Southeast Asia to Australia, throughout Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Australia.

The saltwater crocodile has the widest range of any crocodilian species, spanning from eastern India to New Guinea and northern Australia. Florida is the only region where crocodiles and alligators coexist.

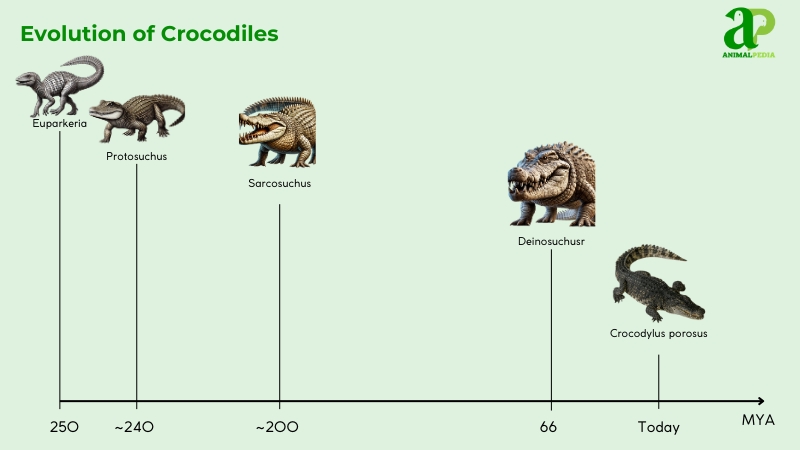

What did Crocodilia evolve from?

Crocodilians (order Crocodilia) evolved from a group of ancient reptiles known as archosaurs, which also gave rise to dinosaurs and birds. Their evolutionary history dates back over 200 million years to the Triassic period.

- Archosaur Ancestors (250 million years ago)

The Crocodilia family tree begins in the Triassic period with the archosaurs, a group of ruling reptiles that also gave rise to dinosaurs and birds. Fossil evidence from this era reveals land-dwelling, bipedal creatures with hollow bones and sharp teeth.

- Early Crocodylomorphs (240 million years ago)

Archosaurs diversified as the Triassic gave way to the Jurassic. One branch, the crocodylomorphs, began developing key features we see in modern Crocodilians, such as a more sprawling posture and an elongated snout. Fossils from this period showcase these transitional forms.

- Aquatic Adaptations (200 million years ago)

The Cretaceous period saw the rise of the dinosaurs, but it was also a time of significant change for the ancestors of Crocodilia. Fossil evidence suggests these early crocodylomorphs began spending more time in the water, developing streamlined bodies and powerful tails for swimming.

- Modern Crocodilians (66 million years ago)

The mass extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs also impacted Crocodilia diversity. However, some lineages survived and evolved into the modern crocodilians we see today. Fossil records from the Paleocene and Eocene epochs provide a good glimpse into these early ancestors of our modern crocs.

What are the behaviors of Crocodilians?

Crocodilians exhibit a wide range of fascinating behaviors that showcase their adaptability, ecological importance, and complex social interactions. These behaviors include their feeding strategies, locomotion techniques, basking habits, territoriality, and reproductive processes, all of which play a critical role in their survival and dominance in aquatic ecosystems:

- Feeding Habits: Crocodilians are apex predators known for ambush hunting and their famous “death roll,” which allows them to subdue and consume prey efficiently. They are opportunistic feeders, consuming a wide variety of prey, from fish and birds to larger mammals.

- Locomotion: Their movement showcases versatility, with streamlined swimming aided by powerful tails, sliding for rapid transitions between land and water, and a unique walking gait for navigating land-based habitats.

- Basking: Thermoregulation through basking helps crocodilians optimize body temperature for hunting, digestion, and overall survival, with favorite basking spots like mud banks, sandbars, and rocks.

- Territoriality: Fiercely territorial, crocodilians use scent marking, vocalizations, and physical displays to establish dominance and attract mates, maintaining control over critical resources.

- Reproduction: Their reproductive strategies include temperature-dependent sex determination, elaborate courtship behaviors, and nest-building, reflecting evolutionary adaptations to ensure offspring survival.

Let’s start by delving into Feeding Habits, which demonstrate the predatory adaptations of crocodilians.

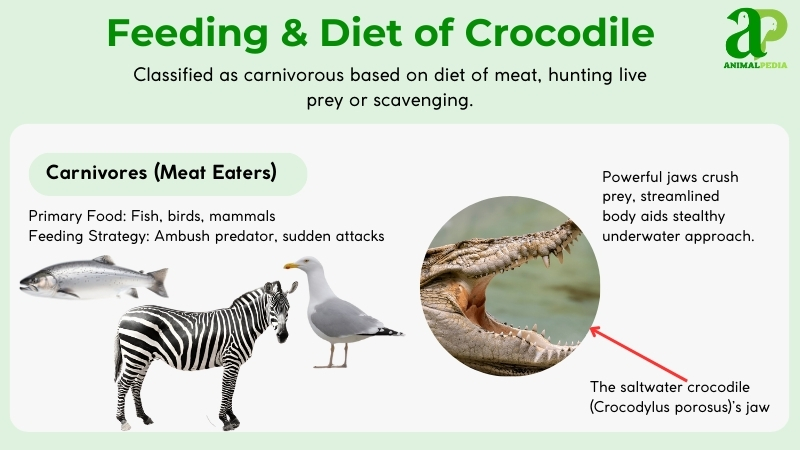

Feeding habits

Crocodiles are apex predators, exhibiting a range of feeding habits that reflect their adaptations to various environments. Crocodiles primarily feed on fish, birds, mammals, and occasionally carrion. Larger species, such as the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), can take down large prey, including deer and livestock.

As ambush predators, crocodiles often lurk beneath the surface, using their camouflaged bodies to blend into their surroundings. They strike quickly and with great force, utilizing their powerful jaws to capture prey. To subdue larger animals, they employ a technique known as the “death roll,” where they spin in the water to tear off chunks of flesh. This method is particularly effective for handling sizable prey.

Feeding habits may vary with the seasons. During warmer months, crocodiles may hunt more frequently due to increased prey availability, while in colder months, they may reduce their activity and feeding. Additionally, crocodiles possess strong stomach acids that allow them to digest bones and tough tissues, making them efficient scavengers.

While generally solitary hunters, crocodiles may congregate in areas with abundant food, showcasing social interactions during feeding. Understanding crocodiles’ feeding habits provides insight into their ecological role and the importance of their presence in aquatic ecosystems. Their predatory behavior not only helps control prey populations but also contributes to the overall health of their habitats.

Locomotion

Crocodilians exhibit three types of locomotion methods, both on land and in water, adapted to their semi-aquatic lifestyle. These are swimming, sliding, and walking.

- Swimming

Crocodilians’ streamlined bodies, combined with short legs, minimize drag, allowing for smooth and effortless movement. The powerful, muscular tail acts like a giant fin, generating strong propulsion and enabling swift navigation through the water. Additionally, their partially webbed feet aid in paddling and precise maneuvering.

To remain submerged without disruption, crocodilians possess specialized features. Their nostrils and ear canals are equipped with special valves that close when underwater, preventing water from entering while still allowing them to detect sounds and vibrations. They rely on a powerful sculling motion of the tail, creating a wave-like movement that propels them forward with agility. In short bursts, they can reach swimming speeds of up to 35 km/h.

Although they are air-breathing reptiles, crocodilians have impressive breath-holding abilities. They can remain submerged for extended periods—sometimes up to an hour—allowing them to hunt stealthily or ambush prey with precision. These adaptations make them highly effective aquatic predators.

- Sliding

Crocodilians use a specialized movement technique called “sliding,” which enables them to move quickly in short bursts. This technique is particularly useful in three key situations. When transitioning between water and land, a crocodilian may slide to achieve a swift, efficient entry or exit. On land, sliding allows for rapid movement over short distances, such as when pursuing prey that has escaped the water. Additionally, crocodiles may incorporate sliding into their hunting strategy, using it to ambush unsuspecting animals near the water’s edge.

Several anatomical adaptations support a crocodile’s ability to slide. Thick, overlapping belly scales protect the underside from abrasions as the animal moves across rough terrain. Powerful legs provide the necessary propulsion, pushing against the ground to generate momentum. While not the primary driver of movement, the tail aids in steering and contributes additional thrust, enhancing the crocodile’s agility during a slide.

- Walking

Regarding walking ability, their limbs are laterally positioned, meaning they sprawl out to the sides of their bodies, unlike our legs, which are positioned underneath. This limits their flexibility and range of motion on land. When walking, they lift their entire body off the ground with each step, move their front and back legs on the same side together in a paddling-like motion, and keep their body relatively straight, with minimal bending at the hips or knees.

Despite their clumsy walk, Crocodilians can move at about 1-2 km/h, with short bursts of speed on land rarely exceeding 10 km/h. Some freshwater Crocodiles can reach speeds of up to 18 km/h.

While they can reach impressive speeds for short bursts, Crocodilians tire quickly on land. They rely on the water for sustained movement. In some studies, the average human walking speed is around 4.8-6.4 km/h, which falls within the range of a crocodile’s slow walk. However, humans can maintain this speed for much longer distances.

Basking

Crocodilians rely on external heat to regulate their body temperature—a process known as thermoregulation. Crocodilians are most active during the day, particularly in the mornings and late afternoons. This is when the sun is at its strongest, providing the ideal conditions for basking. They typically choose exposed areas for basking, such as:

- Mud banks: These provide a warm surface for the Crocodilia to lie on and absorb heat.

- Sandbars: Similar to mud banks, sandbars provide a warm basking spot, especially on sandy riverbanks.

- Rocks: In some cases, Crocodilians may bask on exposed rocks near the water’s edge. The dark color of the rocks absorbs heat effectively, creating a warm basking spot.

Basking has several benefits for Crocodilians. One of which is to increase body temperature. This allows them to become more active and agile when hunting prey. A Crocodilian with a higher body temperature can move faster and react quickly, improving its hunting success.

Another advantage is improved digestion, which helps keep their body temperature warmer and aids in the digestion of food. This is especially important after a crocodile has consumed a large meal. Basking may also help to boost the crocodile’s immune system, making them less susceptible to diseases.

Territoriality

Crocodilians are solitary creatures and fiercely territorial, especially dominant males. They establish and defend specific territories within their habitat, ensuring access to resources like food, mates, and basking areas. As for marking methods, they rely on a combination of:

- Scent marking: They release musky secretions from glands near their cloaca and throat. These secretions can travel through the water, alerting other Crocodilians to their presence.

- Vocalizations: Crocodilians produce a variety of deep bellows, growls, and hisses. These vocalizations serve as territorial warnings to other Crocodilians.

- Body displays: Dominant males may perform impressive displays of strength, such as head bobbing, body slapping on the water, and exposing their throat pouch. This serves as a visual threat to rivals.

There are two reasons why Crocodilians mark their territory. One of which is to defend against rivals, such as other male Crocodilians. This helps to minimize competition for resources and potential fights. Besides, this action helps them to attract mates. Dominant males may use scent marking and vocalizations to attract females within their territory.

If another Crocodilia intrudes on a marked territory, the resident one will likely react aggressively. This may involve threat displays. The resident may perform intensified versions of the displays mentioned earlier, attempting to intimidate the intruder. Moreover, if the intruder persists, a fight might ensue. These fights can be brutal and sometimes lead to serious injuries or even death.

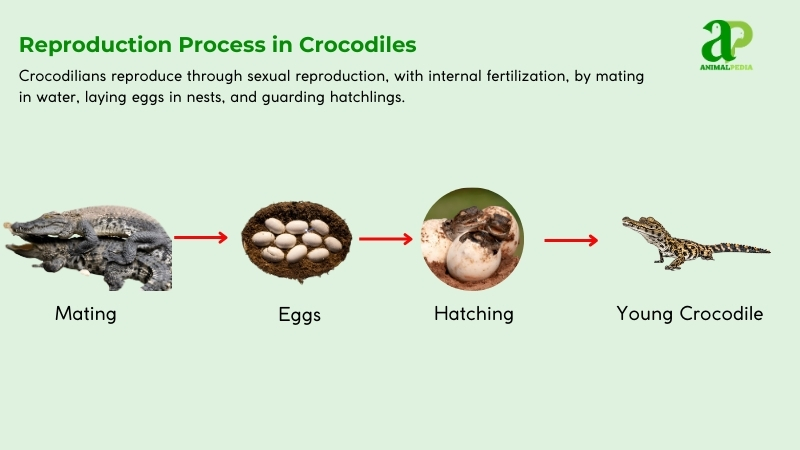

How Do Crocodilians Reproduce?

Crocodilians reproduce sexually, with internal fertilization. They are oviparous, meaning they lay eggs, and exhibit complex parental care compared to many other reptiles.

Once fertilization happens, the female prepares for egg-laying. This preparation involves a period of increased feeding, as she needs to build up energy reserves to nourish the developing eggs. Additionally, hormonal changes stimulate her to find suitable nesting sites. These nests are often located on land near water sources and may be elaborate mounds of mud, vegetation, and debris.

The female Crocodilia lays 20 to 60 leathery eggs within the prepared nest. The sex of the hatchlings is interestingly determined by the incubation temperature. Warmer temperatures produce more females, while cooler temperatures can result in males. The incubation period can last 65 to 95 days, depending on the species and ambient temperature. During this time, the mother Crocodilia may stay close to the nest, offering some protection. However, unlike birds, Crocodilians do not actively incubate their eggs.

Hatchlings are vulnerable upon emergence, and their survival depends on several factors. The incubation environment plays a crucial role. Too much moisture can lead to fungal infections in the eggs, while excessively hot temperatures can be lethal to developing embryos.

Once hatched, the tiny Crocodilians, called hatchlings, are completely independent and fend for themselves. Finding food is a significant challenge, and many succumb to predators or starvation in their early days. However, those that survive this initial vulnerable period grow rapidly and eventually become the apex predators we know today.

Lifespan of Crocodila

On average, Crocodilians can live anywhere between 30 and 75 years. However, some species can exceed this range by far. For instance, the mighty saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) is the longest-lived crocodile, with an average lifespan of around 70 years.

In contrast, some smaller Crocodilia species, like the dwarf Crocodilia (Osteolaemus tetraspis), have a shorter average lifespan of around 30 years.

Here are some examples of lifespan ranges for some common Crocodilia species:

- Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus): 70 years (can exceed 100 years in captivity)

- Nile Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus): 50-60 years

- American Crocodilia (Crocodylus acutus): 40-50 years

- Black caiman (Melanosuchus niger): 30-40 years

- Dwarf Crocodilia (Osteolaemus tetraspis): 20-30 years

Are Crocodilians dangerous to Humans?

Yes, Crocodilians are dangerous to humans due to their complex and often conflicting relationship with people. On the one hand, Crocodilians are not suitable pets. Their large size, powerful jaws, and wild instincts make them dangerous companions. Keeping a Crocodile as a pet is illegal in most places, and even experienced handlers face significant risks.

Zoos play a crucial role in crocodilian conservation. They provide safe havens for these reptiles, educate the public about their importance in the ecosystem, and even participate in breeding programs for endangered species. Living in a zoo provides a controlled environment with proper care and reduces the risks associated with Crocodilians in the wild. However, zoo life can’t fully replicate their natural habitat, which can affect their behavior.

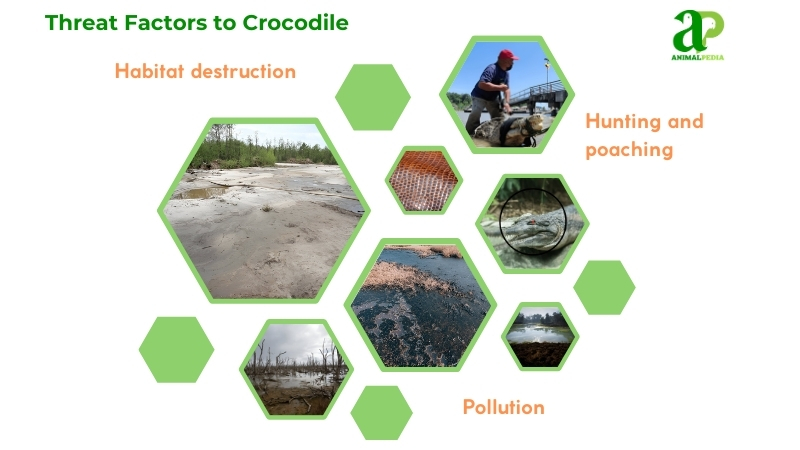

Human also has a huge impact on Crocodilians, which could lead to some negative consequences:

- Habitat destruction: Destroying wetlands and riverbanks disrupts Crocodilia breeding grounds and food sources, threatening their populations.

- Hunting and poaching: Hunting and poaching for meat or trophies can significantly reduce Crocodilia numbers, especially for larger, older individuals.

- Pollution: Pollutants in waterways can harm Crocodilians directly and contaminate their food chain.

As for positives, people have established protected areas for Crocodilians to safeguard their habitat and promote population growth. Additionally, increasing public awareness of the importance of Crocodilia conservation is crucial to their long-term survival.

On the other hand, Crocodilians are undoubtedly dangerous animals. Their powerful jaws and sharp teeth can cause severe injuries or even death. For example, saltwater Crocodiles and Nile Crocodiles are generally considered the most dangerous due to their large size and aggressive nature. Moreover, encroaching on crocodilian territory, disturbing them while nesting, or attempting to swim in crocodile-infested waters significantly increases the risk of an attack.

Are Crocodilians endangered?

They are not invincible, while adult Crocodilians reign supreme in their aquatic territories. Most predators view young Crocodilians as a readily available source of protein, so this could lead to a serious fight. In some cases, large mammals like jaguars might see young Crocodilians as potential competitors for prey and eliminate them. Here are some natural predators that hunt Crocodilians, particularly during their vulnerable stages:

- Large fish: Species such as tiger and bull sharks prey on young Crocodilians, especially those venturing into deeper waters.

- Birds: Birds of prey, such as eagles, hawks, and marabou storks, may target Crocodilia eggs and hatchlings. Their sharp beaks and talons can be deadly for these young reptiles.

- Large mammals: In some areas, large mammals like jaguars, leopards, and hyenas might prey on young Crocodilians that stray too far from the water’s edge.

- Other species: Territorial disputes or fights between large Crocodilians can sometimes result in injuries or even death.

Crocodilians are generally fearless hunters, but even these apex predators have a sense of caution:

- Larger Crocodilians: Smaller Crocodilians might be cautious around much larger individuals, especially during territorial disputes. Smaller Crocodilians can avoid larger ones to prevent serious injuries or death in territorial fights.

- Hippopotamuses: These massive herbivores are incredibly territorial and aggressive. They can threaten Crocodilians, particularly when competing for resources or space. Hippos are formidable opponents, and Crocodilians likely avoid them to minimize the risk of getting hurt.

- Humans: While not a natural predator, humans pose a significant threat to Crocodilians. Hunting and habitat destruction can make Crocodilians wary of human activity.

Conservation

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) maintains a Red List of Threatened Species, categorizing Crocodilians based on their risk of extinction. The status varies depending on the species:

- Critically Endangered: Cuban crocodile, Siamese crocodile, Orinoco crocodile.

- Endangered: Chinese alligator, Philippine crocodile.

- Vulnerable: American crocodile, Mugger crocodile.

- Least Concern: Saltwater crocodile, Nile crocodile.

These classifications were established by the IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group (CSG), a dedicated organization working to conserve Crocodilia worldwide.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) plays a vital role. CITES regulates international trade in endangered species, including crocodile skins and meat. CITES discourages trade in critically endangered and endangered Crocodilia species, promoting sustainable practices for those with less threatened classifications.

There are no exact figures on the total number of Crocodilians left in the world, but estimates suggest over 2 million. The population varies depending on the species:

- Saltwater Crocodile (est. >200,000): These are found in saltwater habitats throughout Southeast Asia, Australia, and parts of the Pacific Ocean.

- Nile Crocodile (not included in the 2 million estimate): found in African freshwater habitats.

- American Crocodilia (not included in the 2 million estimate): These are found in freshwater habitats in Central and South America, Mexico, and the southernmost tip of Florida in the United States.

- Some other Crocodilia species: The Siamese Crocodile and the Orinoco crocodile, are unfortunately listed as critically endangered.

What is the relationship between Crocodilia and Humans?

The relationship between crocodilians and humans is complex, marked by both conflict and cooperation. While attacks and habitat competition create tensions, conservation efforts and economic activities such as tourism and the crocodile leather trade foster a more collaborative dynamic.

- Conflict and Danger

Crocodilian attacks on humans are significant, with approximately 1,000 incidents reported annually, resulting in a nearly 50% fatality rate. The Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) is the most dangerous species, responsible for 300–700 attacks per year in Africa, while the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), the largest living crocodilian, accounts for 30–50 attacks annually in Southeast Asia and Australia.

In Tanzania, around 200 people are attacked by Nile crocodiles each year, particularly near Lake Victoria. In northern Australia, saltwater crocodiles pose a serious threat to swimmers and fishermen, prompting government efforts to capture and relocate large individuals. In Indonesia, habitat destruction due to deforestation has led to an increase in crocodile attacks as they venture into human settlements.

- Cultural and Historical Significance

Crocodiles have been revered in various cultures throughout history. In ancient Egypt, they were associated with the god Sobek, worshipped at the Sobek Temple in Kom Ombo. Some Aboriginal tribes in Australia regard crocodiles as ancestral spirits and perform rituals to appease them. In Indonesia, crocodiles are considered sacred, with local myths depicting them as protectors of holy rivers.

- Conservation and Extinction Risks

Of the 23 recognized crocodilian species, seven are classified as threatened by the IUCN, with two— the Philippine crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis) and the Chinese alligator (Alligator sinensis)—listed as critically endangered, with wild populations of fewer than 100 and 150 individuals, respectively. Conservation programs in China have successfully bred over 10,000 Chinese alligators in captivity.

In the Philippines, dedicated conservation efforts have increased the wild population of the Philippine crocodile from just 10 individuals in 2000 to over 100 by 2023. Similarly, the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), once on the brink of extinction, has rebounded to over two million individuals following protective legislation in 1967. In Australia, large saltwater crocodiles are relocated rather than culled to ensure population stability.

- Economic Value

The crocodile leather industry is a billion-dollar global market, with high-end fashion items such as Hermes Birkin bags fetching prices up to $100,000. Australia and Thailand lead the market, exporting over 100,000 skins annually. Crocodile-related tourism also generates significant revenue.

Gatorland in Florida attracts over 500,000 visitors each year, while Nile crocodile tours in Botswana and Kenya contribute millions to the tourism industry. In Darwin, Australia, crocodile farms draw over 300,000 visitors annually, balancing economic benefits with conservation efforts.

- Ecological Role and Scientific Research

As apex predators, crocodilians play a crucial role in regulating fish and amphibian populations, maintaining ecological balance. In the Everglades, American alligators create natural water holes that support diverse bird and fish species.

Their immune system is also of great scientific interest, as it is up to 100 times more effective at fighting bacteria than the human immune system, offering potential breakthroughs in antibiotic development. Additionally, crocodile skin has natural antimicrobial properties that could aid in wound treatment and infection prevention.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the difference between an alligator and a crocodile?

Here are some differences between an alligator and a crocodile:

- Snout: Alligators have a broad, rounded U-shaped snout, while Crocodilians have a narrow, pointed V-shaped snout.

- Teeth: When an alligator’s mouth is closed, its lower teeth are mostly hidden. A crocodile’s fourth lower tooth sticks out, fitting into a groove in the upper jaw.

- Habitat: Alligators prefer freshwater habitats such as swamps and lakes. Crocodilians are more at home in saltwater habitats, such as coasts and mangroves.

- Color: Alligators are typically darker (black or dark gray), while Crocodilians are lighter (olive green or tan).

- Behavior: Alligators are less aggressive than Crocodiles. Saltwater crocodiles are the most frequent attackers.

- Others: A 2018 study published in the Royal Society Open Science found that crocodilians typically have longer humeri and femora than alligators.

How long do Crocodiles live?

Crocodilians are long-lived reptiles; some estimates suggest they can live for more than 70 years, though their lifespan varies widely, ranging from 25 to 70 years. Some freshwater Crocodiles living in pools, creeks, rivers, and lagoons live for only 40 – 60 years.

How fast can a Crocodile run?

Crocodilians can burst into short sprints of up to 27 km/h on land. Saltwater Crocodiles are among the fastest creatures in water, reaching speeds of up to 35 km/h.

Can alligators and crocodiles mate?

No. According to Owlcation, alligators and Crocodiles are different species and cannot mate with each other.

Can Crocodiles climb trees?

Yes. Some young Crocodilians are agile climbers. They use strong claws and tails to navigate branches and trees near the water’s edge. A study in Herpetology Notes found that five crocodilian species in Africa, Australia, and North America can climb as high as six feet off the ground.

This article provides informative details about Crocodilians, including their definition, characteristics, classification, behaviors, and facts. With around 27 living species, Crocodilians are apex predators thriving in freshwater habitats across tropical and subtropical regions. Recognized for their robust bodies, armored skin, and powerful jaws, they exhibit unique features like interlocking or concealed teeth and impressive bite strength. Please visit Animal Pedia to explore the diversity of animals worldwide.