Geckos, small reptiles with vibrant colors and adhesive toe pads, comprise over 1,500 species worldwide. Their soft skin, large eyes, and slender bodies adapt to diverse ecosystems, from dense rainforests to arid deserts. These lizards thrive on islands like Madagascar and Hawaii, ranging from the tiny 1.6 cm Jaragua sphaero to the robust 40 cm New Caledonian giant gecko.

Key species include the Gekko gecko (tokay gecko), recognized for its distinctive vocalizations, and Phelsuma madagascariensis (Madagascar day gecko), valued for its brilliant green coloration. The Eublepharis macularius (leopard gecko) is a favored pet due to its gentle temperament. These examples showcase the diversity in gecko morphology and behavior.

Geckos’ specialized adaptations include their toe pads that enable vertical climbing and their exceptional night vision. Found primarily across tropical and subtropical regions, they flourish on isolated islands such as the Galápagos and Seychelles. Most species measure under 20 cm. Their regenerative abilities and unique vocalizations, exemplified by the tokay’s bark-like call, set them apart from other reptiles.

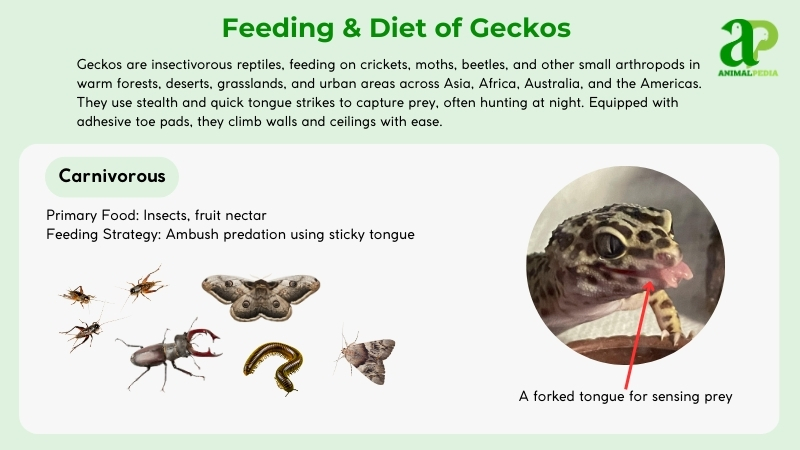

In their ecological niche, geckos function as mid-level predators, employing stealth tactics to capture insects, arachnids, and small vertebrates. Nocturnal species depend on highly developed sensory systems. Their diet consists mainly of insects, though some species consume fruit or nectar. Human interactions vary—leopard geckos thrive in captivity, while tokays feature prominently in Asian folklore and traditional medicine.

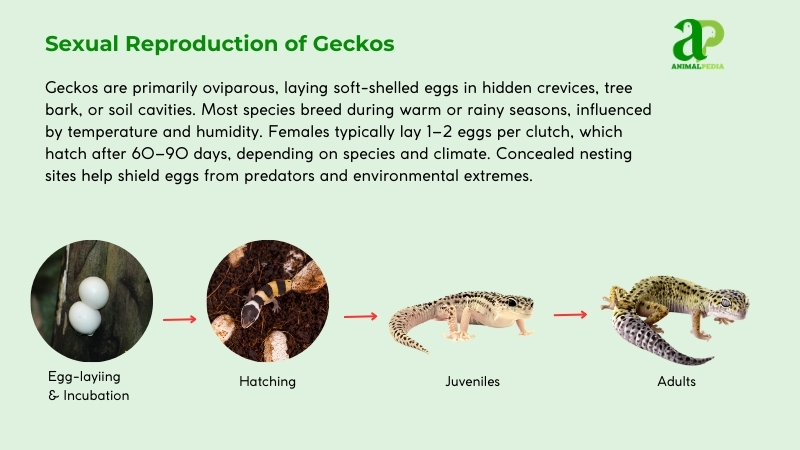

Reproduction intensifies during warmer months. Females typically deposit 1–2 eggs per clutch in protected locations. Incubation spans 30–90 days, varying by species and environmental temperature. Hatchlings emerge self-sufficient, hunting independently within days. Sexual maturity occurs at 1–2 years, with lifespans ranging from 5–15 years in the wild.

This article examines geckos’ physical characteristics, habitat preferences, and behavioral patterns, emphasizing their ecological significance and evolutionary adaptations.

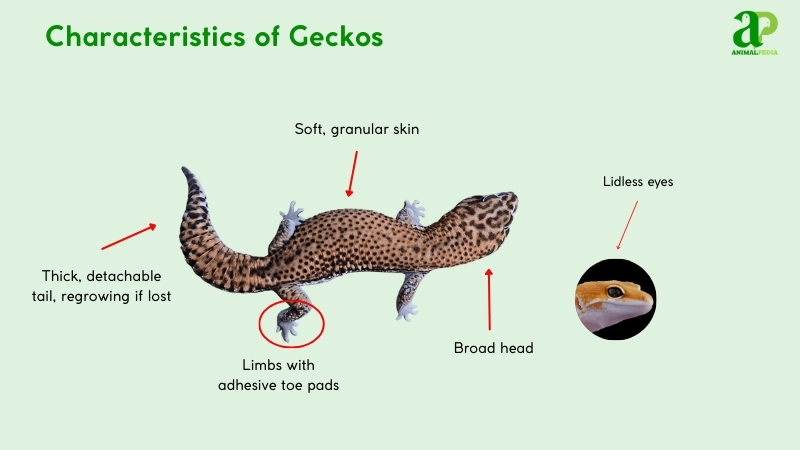

What do the Geckos look like?

Geckos have compact, elongated bodies with soft, granular skin covered in tiny scales. Their coloration varies widely – from vibrant greens in day geckos (Phelsuma spp.) to mottled grays in tokays (Gekko gecko). Most species display spots or stripes that serve as camouflage. Their velvety skin helps retain moisture.

Key physical features include a broad head with large, lidless eyes adapted for night vision; a forked tongue for detecting prey; a short neck; a slender torso; four limbs with specialized adhesive toe pads; and a thick, detachable tail that can regrow if shed. Geckos typically measure 5-15 cm in length.

Unlike chameleons, geckos can’t change color or grip with their tails. Their specialized toe pads – unique among lizards – contain microscopic structures that enable vertical climbing through molecular adhesion, distinguishing them from skinks, which have smooth feet. The tokay gecko’s distinctive barking vocalization separates it from quieter anole species, while day geckos’ daytime activity patterns contrast with the predominantly nocturnal habits of most gecko species (Gamble et al., 2017).

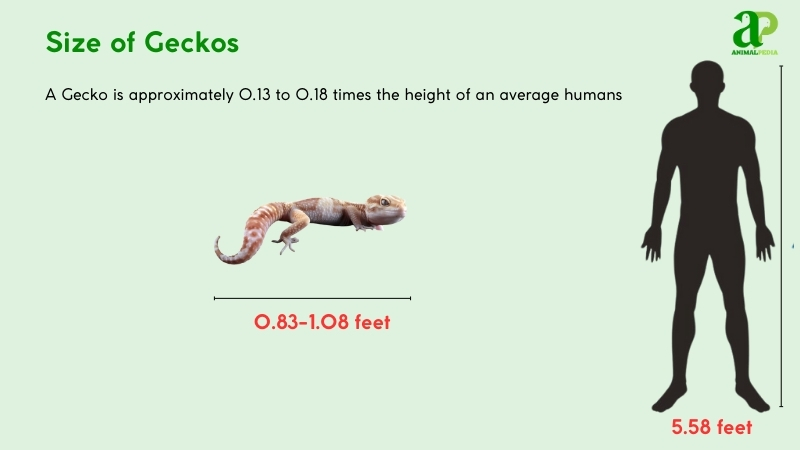

How big do Geckos get?

Geckos average 4-8 inches (10-20 cm) in length and weigh 0.03–0.11 lbs (15-50 grams). Most species stay compact, fitting their arboreal lifestyles.

The largest is the New Caledonian giant gecko (Rhacodactylus leachianus), which reaches 17 inches (43 cm) and 0.88 lbs (400 grams) and is found in New Caledonia’s forests, per Bauer (2019). Adult tokay geckos (Gekko gecko) typically hit 12 inches (30 cm) snout to tail. Males are slightly larger and heavier than females, with broader heads for territorial displays.

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 11–13 inches (28-33 cm) | 10–12 inches (25-30 cm) |

| Weight | 0.13–0.22 lbs (60-100 g) | 0.11–0.18 lbs (50-80 g) |

What are the unique physical characteristics of the species?

Geckos possess specialized adhesive toe pads, a trait found in few vertebrates, enabling them to climb vertical surfaces and even hang from ceilings. Unlike other reptiles, these pads use millions of microscopic setae that create van der Waals forces for grip without requiring sticky secretions.

Research by Autumn et al. (2018) shows that each seta—approximately 0.2 micrometers wide—generates enough adhesive force to support a gecko’s weight several times over. This evolutionary adaptation, absent in related lizards such as skinks and anoles, allows geckos to navigate across smooth glass, rough leaves, and rocky surfaces—even in inverted positions. This biomechanical innovation makes geckos uniquely adapted for both natural arboreal habitats and human-made urban environments.

How do Geckos sense their environment with its unique features?

Anatomy

Geckos possess specialized internal systems that enhance their survival in diverse environments, particularly arboreal and nocturnal habitats. Their physiology reflects adaptations for agility, stealth, and efficiency in warm, often dry ecosystems.

- Respiratory System: Simple lungs with thin walls enable efficient oxygen exchange, ideal for rapid climbing in humid environments.

- Circulatory System: A three-chambered heart pumps blood, sustaining energy for quick movements and nocturnal hunting.

- Digestive System: A short tract digests insects swiftly, with strong stomach acids breaking down chitin-rich prey.

- Excretory System: Kidneys filter uric acid, conserving water in dry habitats, producing concentrated waste.

- Nervous System: Compact brain and sharp sensory nerves drive fast reflexes, aiding predator evasion and prey capture.

These physiological systems collectively enhance geckos’ adaptability to challenging ecosystems, ensuring their success as small but highly efficient insectivores in tropical and subtropical regions.

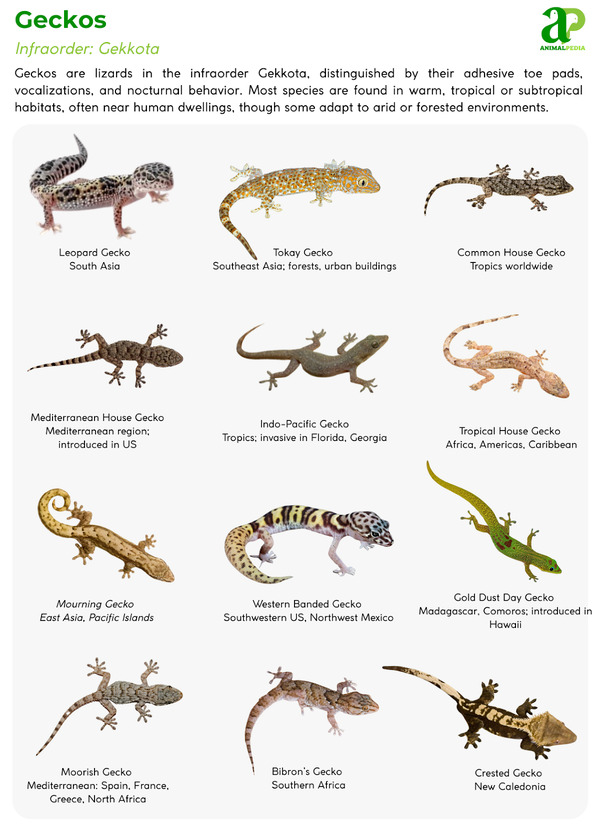

How many types of Geckos?

Over 2,000 gecko species exist within the Order Squamata. Classification is based on the Linnaean system, developed by Carl Linnaeus, which groups organisms by traits such as toe pad structure and reproductive modes.

The taxonomy branches as: Order Squamata → Families (e.g., Gekkonidae, Carphodactylidae) → Genera → Species.

Order Squamata

├── Family Gekkonidae

│ └── Genus Gekko (e.g., G. gecko)

└── Family Carphodactylidae

└── Genus Carphodactylus (e.g., C. laevis)

Special cases include parthenogenetic species like Lepidodactylus lugubris, reproducing without males, defying typical classification.

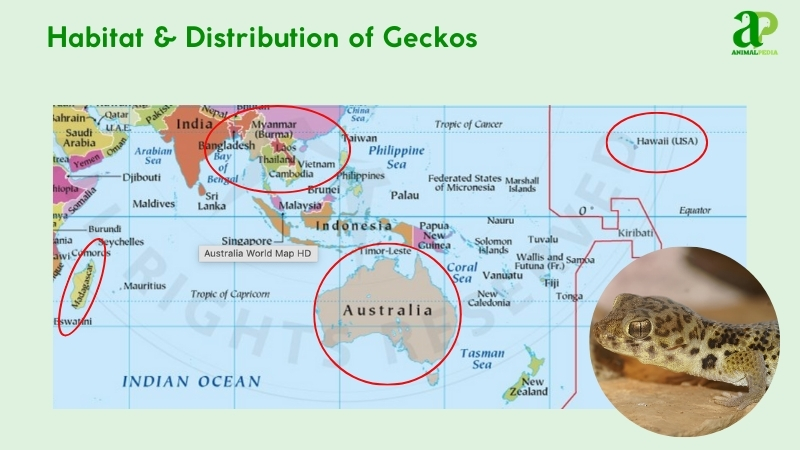

Where do Geckos live?

Geckos live in warm tropical and subtropical regions worldwide. They thrive in Madagascar’s lush rainforests, Australia’s arid outback, and Hawaii’s rugged volcanic slopes. Biodiversity hotspots like New Caledonia and Southeast Asia’s dense jungles host particularly high concentrations of gecko species.

These reptiles prefer humid environments with abundant vegetation and rocky surfaces. Their specialized adhesive toe pads allow them to exploit vertical habitats inaccessible to other animals, clinging to trees, rocks, and even smooth surfaces.

According to herpetologist Aaron Bauer (2019), gecko populations have inhabited these ecological niches for millions of years. Their habitat fidelity is strong, with minimal migration patterns due to the relatively stable environmental conditions in their native regions.

How do seasonal changes affect their behavior?

Geckos, especially those in tropical environments, exhibit seasonal behavioral shifts to align with environmental changes in temperature, humidity, and prey availability. These cycles directly affect their activity, reproduction, and survival strategies. Geckos adapt to two seasons in tropical regions: wet (April–September) and dry (October–March).

- Wet Season (April–September): Increased rainfall boosts insect prey, spurring nocturnal hunting and mating activity.

- Dry Season (October–March): Reduced food leads to less movement; geckos conserve energy, hiding in crevices.

These seasonal adjustments reflect geckos’ ability to maintain energy balance and reproductive success in fluctuating tropical climates.

What is the behavior of Geckos?

Geckos exhibit behaviors perfectly suited to their nocturnal and arboreal nature. These patterns help them thrive in both forest canopies and urban settings throughout warm regions worldwide.

- Feeding Behavior: They ambush insects, especially moths, with lightning-fast tongue strikes. Their diet consists exclusively of arthropods, making them valuable pest controllers.

- Defense Mechanisms: Non-venomous reptiles, such as geckos, bite only when threatened. Larger species, such as Tokay geckos, may deliver warning nips when handled improperly.

- Activity Patterns: Strictly nocturnal, these lizards shelter during daylight hours. They typically patrol territories spanning 2-5 meters after sunset, with peak hunting activity occurring at dusk and dawn.

- Movement Capabilities: Their adhesive lamellae (specialized toe pads) enable vertical climbing on almost any surface. They move with agility, using their tails for balance during rapid lateral movements.

- Social Organization: Predominantly solitary creatures, geckos interact primarily for reproduction. Males establish and actively defend small territories from rivals.

- Acoustic Communication: Many species produce distinctive vocalizations—barks, chirps, and clicks—to announce territory ownership or attract mates. Body language complements these sounds through head-bobbing and tail-waving displays.

These adaptive behaviors enable geckos to efficiently capture prey, secure mates, and avoid predators within the complex three-dimensional habitats they occupy.

What do Geckos eat?

Geckos are carnivorous, primarily feeding on insects such as crickets, moths, and beetles. They do not attack humans; they focus solely on small invertebrates.

- Diet by Age

Hatchlings consume tiny insects, such as fruit flies, while adults hunt larger prey, such as beetles and worms.

- Diet by Gender

Males and females share similar diets, targeting the same insect species with no preference distinction.

- Diet by Seasons

During the wet season (April–September), prey like moths become abundant, increasing feeding activity. In the dry season (October–March), food becomes scarcer, limiting intake to smaller insects like flies.

Across all ages and sexes, geckos use stealth and quick tongue strikes to ambush prey. They swallow prey whole, crushing exoskeletons with powerful jaws. Oversized prey can lead to choking and may be regurgitated, per Bauer (2019.

How do Geckos hunt their prey?

Geckos hunt with deadly efficiency. They target insects like crickets, flies, and spiders using keen vision to spot movement. These reptiles stalk slowly, then pounce with explosive speed. Their limbs work as natural springs, launching them at prey with precision.

The gecko’s famous adhesive toe pads give them a hunting edge. They climb walls and ceilings without effort, attacking from above or below. This three-dimensional hunting strategy enables them to approach prey from unexpected angles, thereby increasing their success rate across various microhabitats.

Some gecko species exhibit aerial hunting. They leap and intercept flying insects mid-air, demonstrating exceptional spatial awareness and reflexes. Their hunting behavior showcases the evolutionary adaptations that make these small lizards such effective predators in their ecological niches.

Are Geckos venomous?

The majority of geckos you come across aren’t venomous. Geckos use their speed, agility, and sharp teeth to capture their prey, rather than relying on venom.

They’ve fascinating hunting techniques that involve chasing down insects and small creatures in their natural habitats. While some geckos may have mild toxins in their saliva to immobilize their prey, these substances are harmless to humans.

Geckos’ hunting skills are truly worth observing in action, showcasing their unique adaptations for survival in the wild.

When are Geckos most active during the day?

Geckos are nocturnal creatures, most active after sunset rather than during daylight hours. They use their exceptional night vision to hunt insects in the dark. These reptiles hide during the day, conserving energy in sheltered spots.

When darkness falls, geckos emerge with agility and stealth. Their specialized toe pads enable them to climb vertical surfaces while searching for prey such as moths, mosquitoes, and spiders. This nighttime activity pattern helps them avoid diurnal predators such as birds and larger lizards.

Gecko species around the world share this pattern, from the common house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus) to regional species like the Mediterranean House Gecko, which thrives in warm coastal environments and urban settings. Their eyes, packed with rod cells, are adapted to capture minimal light, granting superior night vision compared to most reptiles.

If you want to observe geckos in action, evening hours provide the best opportunity. Their hunting prowess and climbing abilities become apparent as they patrol walls and ceilings after dark, demonstrating evolutionary adaptations perfected over millions of years.

While occasional daytime sightings occur, particularly in disturbed habitats, their peak activity period consistently happens during nighttime hours when temperatures drop and insect prey becomes abundant.

How do Geckos move on land and water?

Geckos are masters of movement across both land and water, utilizing specialized adaptations for each environment.

On land, gecko locomotion relies on their adhesive toe pads with millions of microscopic setae that enable them to grip surfaces through van der Waals forces. They move with a lateral undulation pattern, alternating limb pairs while keeping low to the ground.

In water, these reptiles employ a hydrophobic skin that repels water. When swimming, geckos use limb paddling combined with lateral tail movements for propulsion. Some species can even perform a feat called water running, where they use a combination of surface tension and rapid limb movement to briefly sprint across water surfaces.

The tokay gecko and day geckos exemplify this dual locomotion capability, shifting between terrestrial and aquatic movement with efficiency. Their musculoskeletal system permits quick direction changes and swift acceleration in both environments.

This biomechanical versatility explains why geckos have successfully colonized diverse habitats, from tropical rainforests to arid deserts, making them exceptional models for bioinspired robotics research.

Do Geckos live alone or in groups?

Geckos are known to live solitary lives, preferring to establish their territories on their own rather than in large social groups.

This behavior allows them to roam and hunt independently, choosing their basking spots or shelter without considering others’ preferences. Geckos enjoy the independence of solitary living, navigating their habitats with individuality and self-sufficiency.

How do Geckos communicate with each other?

Geckos have unique ways of communicating despite their solitary nature. They use body language, such as head bobbing and tail wagging, to convey messages like aggression or attraction.

Another way geckos communicate is through vocalizations such as chirps and clicks. Moreover, geckos use scent marking, using special glands to release pheromones to establish territories and communicate with potential mates or rivals.

This blend of visual cues, sounds, and scents allows geckos to interact effectively in their environment.

How do Geckos reproduce?

Geckos reproduce oviparously, laying eggs. Breeding occurs during the wet season, from April to August. Males attract females through loud chirps and tail-waving displays. Females signal receptiveness with subtle head bobs. Mating follows, with males briefly grasping females during copulation in hidden locations.

Females deposit 1-2 eggs per clutch, each weighing 0.5-1 gram. They attach eggs to rocks or tree bark with adhesive secretions. Mothers provide no nest protection; the eggs rely on natural camouflage. After mating, males and females separate. Environmental factors like drought or predation can disrupt egg-laying, as documented in 2017 research during El Niño events.

Incubation lasts 60-90 days, according to Bauer (2019). Hatchlings emerge 3-5 cm long and immediately fend for themselves, feeding on tiny insects. Growth happens rapidly, with sexual maturity reached in 1-2 years.

The life cycle spans 7-15 years. Some gecko species, including Lepidodactylus lugubris, reproduce through parthenogenesis—development without male fertilization.

How long do Geckos live?

Geckos typically live 7-15 years. They develop from egg to adulthood in 1-2 years. Some species, such as Lepidodactylus lugubris, reproduce asexually through parthenogenesis, an uncommon reproductive adaptation among reptiles.

The average lifespan of common species such as tokay geckos (Gekko gecko) ranges from 8 to 12 years. According to Bauer’s 2019 research, male and female geckos generally share similar longevity patterns.

Wild geckos face shorter lifespans than their captive counterparts due to natural predation, environmental stressors, and food scarcity. Proper husbandry in captivity—including appropriate temperature regulation, nutritional balance, and habitat enrichment—can substantially extend a gecko’s life expectancy.

What are the threats or predators that Geckos face today?

Geckos face mounting threats across their native tropical habitats. Environmental changes have triggered population declines, especially among forest-dependent species.

- Habitat destruction devastates gecko populations. Deforestation eliminates crucial climbing surfaces, slashing numbers by 30% in affected regions. Urbanization and agricultural expansion further fragment their territories.

- Climate change disrupts gecko survival patterns. Rising temperatures alter prey availability and seasonal cycles, reducing reproduction rates by 15%. Desert species are particularly susceptible to thermal stress.

- Invasive predators decimate gecko populations. Introduced rats, cats, and mongoose target eggs and juveniles, cutting hatchling survival by 25% in many island ecosystems.

- Agricultural chemicals contaminate their environments. Pesticides diminish insect populations, reducing gecko food sources by approximately 20% in farming regions.

Geckos face numerous natural hunters, including:

- Avian predators (hawks, owls, herons)

- Reptilian hunters (snakes, larger lizards)

- Mammalian threats (small carnivores, rodents)

Human activity is the most significant threat. Research by Woinarski et al. (2018) demonstrates that land clearing has reduced gecko ranges by 25% in Australia since 2000, highlighting the conservation challenges these reptiles face.

Are Geckos endangered?

Most gecko species are non-endangered, though conservation status varies significantly. The IUCN Red List classifies the Union Island gecko (Gonatodes daudini) as “Critically Endangered,” while the Tokay gecko (Gekko gecko) maintains “Least Concern” status.

The Union Island gecko, endemic to Saint Vincent’s Union Island in the Caribbean, faces extinction with a population below 500 individuals. Habitat destruction threatens its survival, according to Powell’s 2019 research. In contrast, Tokay geckos thrive across Southeast Asia with populations in the millions, adapting to diverse ecosystems, including human settlements.

The reptile family Gekkonidae generally maintains stable numbers, but specific species face critical threats. Primary dangers include deforestation, illegal wildlife trafficking, and climate change. These pressures have reduced certain localized gecko populations by approximately 20% over the past few decades.

What conservation efforts are underway?

Global gecko conservation efforts focus on three key strategies: habitat protection, invasive species control, and trade regulation. Fauna & Flora International has successfully protected Union Island geckos (Gonatodes daudini), increasing their population from critical levels to over 18,000 specimens by 2023. Similarly, the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources eliminated invasive rats on Monito Island, allowing the endemic Monito gecko (Sphaerodactylus micropithecus) population to rebound to 7,600 individuals by 2019.

International legislation provides crucial protection for threatened gecko species. CITES Appendix II listing for tokay geckos (Gekko gecko) in 2019 restricts unregulated exports and combats illegal wildlife trafficking. Regional laws, such as India’s Wildlife Protection Act (amended 2022), strengthen enforcement, with authorities in Assam confiscating 11 illegally captured tokay geckos in 2025.

Ex-situ conservation through captive breeding represents another vital component. The Association of Zoos and Aquariums coordinates breeding programs for threatened gecko taxa, particularly Phelsuma species, achieving a 38% reproduction success rate by 2023. Specialized facilities like Reunion Reptiles have maintained consistent breeding success with endangered Phelsuma klemmeri since 2018.

Conservation success stories demonstrate effective interventions. The Monito gecko earned delisting from the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 2019 following successful rat eradication. Union Island geckos were recovered through a combination of community-based conservation patrols and legal protection via CITES listing in 2018, as documented by Powell et al. (2019).

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Geckos Harmful to Humans or Pets?

Geckos are generally not harmful to humans or pets. They mostly eat insects and can help control pests. Keep a friendly coexistence with geckos, as they help maintain a natural balance in your environment.

Can Geckos Change Their Color Like Chameleons?

Sure, geckos can’t change color like chameleons do. Geckos have pretty consistent colors but might change shades due to stress, temperature, or their surroundings. Chameleons, on the other hand, have specialized cells that allow them to change color.

Do Geckos Steal Food From Other Animals?

Yes, geckos may opportunistically snatch food from insects or other small creatures. Their quick movements and hunting skills allow them to catch prey efficiently, helping them survive in their natural habitats.

Are Geckos Social or Solitary Creatures?

You might find it interesting that geckos can be both social and solitary creatures. They may choose to interact with others or go about their business alone, depending on their mood or circumstances.

How Do Geckos Defend Themselves From Predators?

To defend themselves from predators, geckos use their unique ability to drop their tails when threatened. This action distracts predators, allowing geckos to escape. This regrown tail will not replace the original in appearance but serves a functional purpose.

Conclusion

Geckos stand as reptiles with their vibrant scales, adhesive toe pads, and precise hunting techniques. Their ability to modify skin pigmentation for camouflage and their acrobatic mobility make them formidable predators in their ecosystems. These lizards thrive across diverse habitats, from tropical rainforests to arid deserts, displaying adaptive resilience. With specialized lamellae that generate van der Waals forces, geckos can scale vertical surfaces and even traverse ceilings—a feat that continues to inspire biomimetic engineering. Their nocturnal behaviors, distinctive vocalizations, and regenerative capabilities further distinguish them in the reptilian world. The enduring fascination with these creatures stems from their evolutionary success and specialized adaptations, which have enabled them to flourish for millions of years.