Lizards are fascinating cold-blooded vertebrates within the order Squamata, which also includes snakes. With around 7,000 species identified worldwide (Reptile Database, 2024), they are among the most diverse vertebrate groups.

Key traits include external ears, movable eyelids, and behavioral thermoregulation for controlling body temperature. Lizards also display autotomy, the ability to detach and regenerate their tails as a defense mechanism.

Their origins date back 150 million years to the Late Jurassic, with fossils such as Paramacellodus offering crucial evolutionary insights (Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology). These adaptable reptiles inhabit a wide range of ecosystems, from rainforests to deserts, and exhibit dietary diversity, with most being insectivorous and some herbivorous.

Human relationships with lizards are complex. They are appreciated as pest controllers and exotic pets but face threats from habitat loss and human activities. Conservation efforts, like protecting Komodo dragons in Indonesia, highlight their ecological importance. Lizards’ adaptability and evolutionary history underscore their significance in biodiversity.

Let’s go on a fascinating journey through the world of lizards, exploring the vibrant diversity and intriguing adaptations of these reptiles that have thrived on Earth for millions of years.

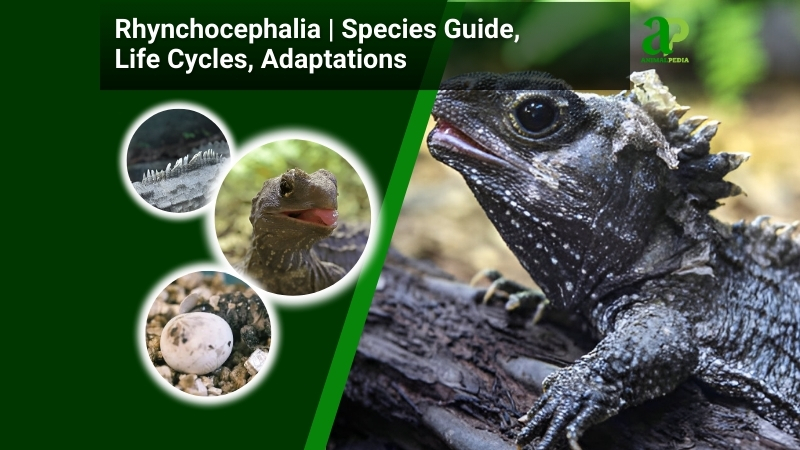

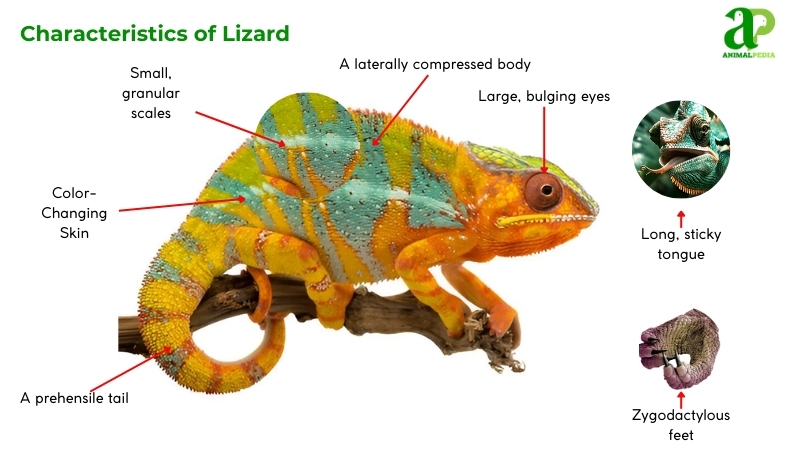

What are Lizard’s characteristics?

Here are some detailed characteristics of lizards that showcase their incredible adaptability and survival strategies.

- Scales provide protection, camouflage, and moisture retention.

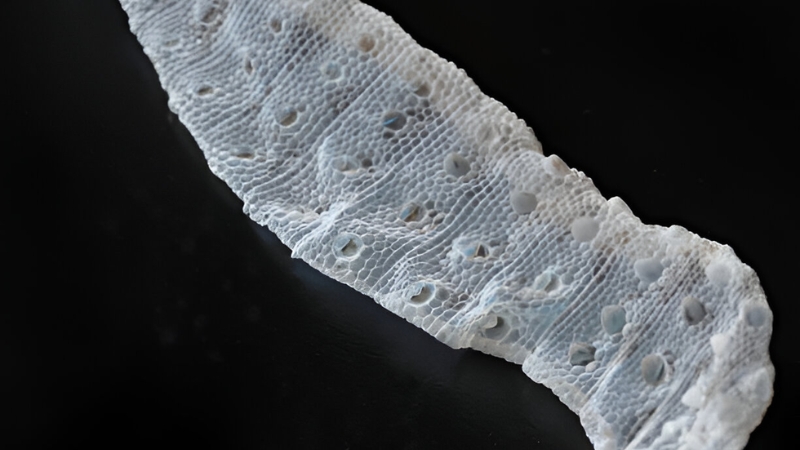

- The skin shedding process, which supports growth, health, and nutrient recycling.

- Tails, including balance, fat storage, and defense.

These features collectively highlight the evolutionary innovations that have allowed lizards to thrive in diverse habitats across the globe:

Scales

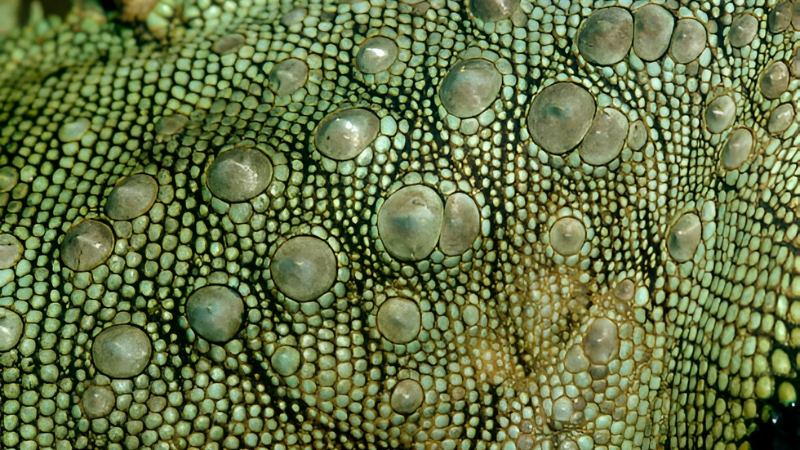

The scales of lizards are complex and multifunctional, consisting of two primary layers: the outer epidermis and a deeper dermis layer. The epidermis is composed of beta-keratin, the same durable material found in human hair and nails, which provides a sturdy outer shield. Beneath this lies the dermis, offering additional support and structure. Lizard scales vary in texture and shape, ranging from smooth to keeled (ridged) and granular, each type serving different roles in adaptation and survival.

These scales serve as formidable armor, protecting lizards from abrasion, environmental hazards, and predators. Certain species, like the Gila Monster, possess osteoderms—bony plates under their scales—that provide an extra layer of defense. Beyond protection, scales play a crucial role in camouflage. Their coloration and patterns enable lizards to blend seamlessly into their surroundings, with some species capable of changing color to match their environment more closely, aiding in their camouflage, though not as extensively as chameleons.

Furthermore, scales are integral in minimizing water loss, a critical adaptation for species inhabiting arid deserts. They are tightly overlapped to prevent dehydration, ensuring the lizard’s survival in dry climates. Additionally, specialized scales enable certain lizards, such as desert species and geckos, to navigate their unique habitats effectively. For example, geckos have specialized toe pads that allow them to adhere to and climb vertical surfaces, while certain desert lizards have scales that facilitate movement on loose, sandy terrain.

Skin Shedding

Skin shedding, or ecdysis, is a vital process for lizards, enabling them to grow and maintain healthy skin. This intricate procedure begins with the formation of a new skin layer beneath the old one. As the new layer develops, the lizard secretes a fluid between the old and new layers, facilitating their separation. This allows the old skin to come off, which can occur in pieces or as a single dramatic shed, depending on the species and the individual’s condition.

The frequency of skin shedding in lizards is primarily influenced by their growth rate, age, and environmental factors. Younger lizards, which grow more rapidly, shed their skin more frequently than older ones. Environmental conditions, such as humidity and temperature, also play a significant role in determining how often a lizard sheds its skin, with optimal conditions promoting more frequent shedding.

Many lizards, such as geckos, iguanas, and bearded dragons, eat their shed skin. This behavior serves multiple purposes: it recycles valuable nutrients back into their bodies, helping them conserve energy. Additionally, by consuming their shed skin, lizards effectively remove evidence of their presence, making it harder for predators to track them down. This combination of nutritional and protective benefits highlights the efficiency and adaptability of lizards in their natural habitats.

Tails

Lizard tails serve multiple critical functions, from facilitating movement to offering a means of defense. These versatile appendages are integral to the survival strategies of various species.

Balance and Movement:

- Lizard tails act as counterweights, enhancing stability and agility during movement. This is especially evident in species like the basilisk lizards, which can run bipedally across water surfaces, using their tails to balance and steer.

- Tails provide additional support in climbing and navigating complex terrains. Arboreal species, for example, rely on their tails for balance as they move through the canopy, allowing for precise and safe navigation through trees and bushes.

Fat Storage:

- For many lizards, tails are vital energy reserves, where fat is stored for periods when food is scarce. Species in desert or seasonal environments often have noticeably thicker tails, serving as a buffer against food shortage.

Defense:

- Autotomy, or the voluntary release of the tail, is a defense mechanism in lizards. When grabbed by a predator, a lizard can detach its tail, leaving it behind as a distraction. This tail will often continue to wriggle, drawing the predator’s attention away from the lizard itself. The tail is then regenerated through complex muscle mechanisms, although the new tail may differ in appearance.

- Like certain species of spiny-tailed lizards, some lizards possess tails covered in sharp spines. These spiky tails can be used as formidable weapons against predators, delivering painful thwacks to deter or injure aggressors.

- Prehensile tails are a special adaptation found in some arboreal lizard species that function like an extra limb. These tails can grasp and wrap around branches, providing stability and support as the lizard climbs or hangs. This adaptation benefits dense forests or jungles where mobility and security are paramount.

Which is the exception of Lizards?

Among these, Amphisbaenians, or worm lizards, stand out for their specialized subterranean lifestyle and unique features.

Amphisbaenians exhibit significant anatomical changes for underground living. Most species are limbless, an adaptation that enhances their burrowing efficiency, except for the Mexican burrowing lizard (Bipes biporus), which retains small, functional forelimbs. Their accordion-like movement through soil exemplifies their exceptional burrowing capabilities (Journal of Morphology, 2022).

Their underground existence has driven further adaptations. Heavily reinforced skulls, up to 50% denser than those of surface-dwelling lizards, act as effective digging tools and protect tunneling (University of Florida, 2023). Additionally, their vestigial eyes, covered by protective scales, mark a significant departure from the well-developed vision of most lizards, perfectly suiting their dark habitats.

These adaptations have enabled Amphisbaenians to thrive in diverse underground environments across the Americas, Africa, and Europe. By exploiting this niche, they avoid competition with surface predators and gain access to plentiful resources, such as underground insects and larvae.

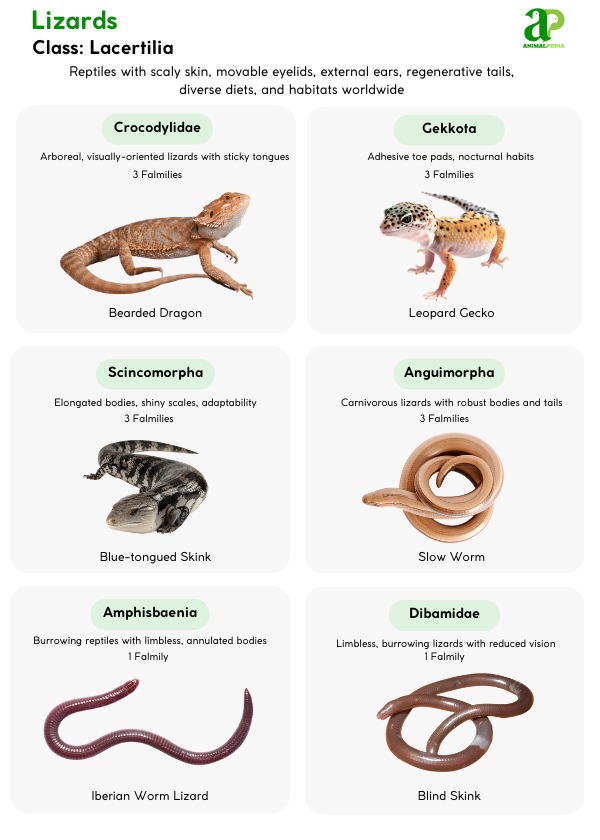

How are Lizards classified?

Lizards belong to the order Squamata within the class Reptilia. They are classified into various families, genera, and species based on morphological characteristics, habitat preferences, behavior, and reproductive strategies. The systematic classification of lizards has evolved over time, with significant contributions from herpetologists who study reptilian and amphibian classification.

The classification of lizards is primarily based on features such as body shape and scale arrangement. These features can be extreme, such as the famous flattened body and defensive “horns” (which are specialized scales) of the Horned Lizard. The head structure, limb structure, and coloration also play crucial roles in classification. Additionally, the tail type (long or short) and the method of locomotion are important criteria.

Lizards are further divided into several families, each with unique characteristics:

- Family Iguanidae: This family includes iguanas and related species, known for their robust bodies and herbivorous diets. They often display vibrant colors and distinctive throat sacs.

- Family Agamidae: Family Agamidae: Commonly known as dragon lizards, this family includes a variety of unique reptiles, with the most famous example being the Frill-necked Lizard and its iconic defensive frill.

- Family Chamaeleonidae: Chameleons are renowned for their ability to change color, their prehensile tails, and their unique zygodactylous feet adapted for climbing.

- Family Scincidae: Skinks, characterized by their smooth, shiny scales and elongated bodies, often have reduced or absent limbs. They are highly adaptable and can be found in a range of environments.

- Family Varanidae: This family includes monitor lizards, known for their large size, strong limbs, and keen sense of smell. They are often active predators and can be found in diverse habitats.

- Family Teiidae: The teiids, or whiptails, are known for their agility and speed. Many species exhibit distinct coloration and patterns, and some are parthenogenetic, reproducing without males.

- Family Eublepharidae: This family consists of eyelid geckos, characterized by their movable eyelids and lack of adhesive toe pads, differentiating them from other gecko families.

In summary, the classification of lizards is a complex process that incorporates morphological, behavioral, and genetic data. As research progresses, our understanding of their diversity and evolutionary history continues to expand, reflecting the intricate relationships within the reptilian world.

Lacertilia (Lizards)

│

├── Infraorder: Iguania

│ ├── Family: Iguanidae (~45 species)

│ ├── Family: Agamidae (~400 species)

│ ├── Family: Chamaeleonidae (~200 species)

│

├── Infraorder: Gekkota

│ ├── Family: Gekkonidae (~1,500 species)

│ ├── Family: Pygopodidae (~40 species)

│ ├── Family: Phyllodactylidae (~160 species)

│

├── Infraorder: Scincomorpha

│ ├── Family: Scincidae (~1,700 species)

│ ├── Family: Lacertidae (~300 species)

│ ├── Family: Teiidae (~150 species)

│

├── Infraorder: Anguimorpha

│ ├── Family: Anguidae (~100 species)

│ ├── Family: Helodermatidae (2 species)

│ ├── Family: Varanidae (~80 species)

│

├── Infraorder: Amphisbaenia

│ ├── Family: Amphisbaenidae (~200 species)

│

├── Infraorder: Dibamidae

│ ├── Family: Dibamidae (~20 species)

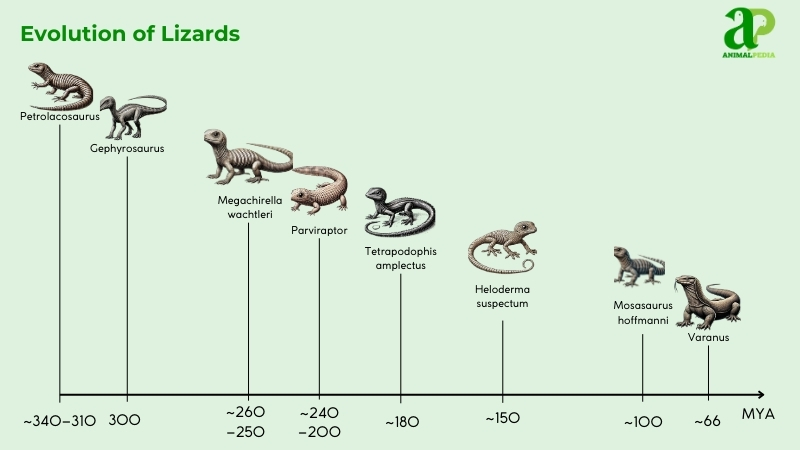

What did Lizards evolve from?

The evolutionary journey of lizards spans hundreds of millions of years, revealing a story of adaptation and survival. From their humble beginnings as early land vertebrates to becoming one of the most diverse reptile groups today, lizards have continuously evolved to thrive in countless environments worldwide. Let’s explore this fascinating timeline.

- Origin of Amniotes (~340–310 million years ago, Late Carboniferous)

Amniotes evolved from amphibian-like tetrapods, developing eggs with protective membranes. This innovation freed them from aquatic reproduction, allowing full land colonization. Early amniotes split into synapsids (leading to mammals) and sauropsids (leading to reptiles), setting the foundation for lizard evolution.

- Rise of Sauropsids and Early Reptiles (~310–300 million years ago, Carboniferous to Early Permian)

Sauropsids emerged with scaly skin and efficient lungs for terrestrial life. They became dominant land vertebrates, diversifying into anapsids (turtles) and diapsids (leading to lizards, snakes, birds, and crocodiles). Early diapsids were small and lizard-like with two skull openings for improved muscle attachment.

- Emergence of Lepidosaurs (~260–250 million years ago, Late Permian to Early Triassic)

Diapsids split into archosaurs (dinosaurs, birds, crocodiles) and lepidosaurs. Lepidosaurs—direct ancestors of modern lizards—developed overlapping scales and more flexible skeletons. Early lepidosaur fossils, such as Sophineta, exhibit transitional features that would later become characteristic of modern lizards.

- First Squamates (~240–200 million years ago, Middle Triassic to Early Jurassic)

Squamata emerged within lepidosaurs, developing advanced jaw flexibility and specialized scales. This order marks the origin of true lizards and their relatives. Megachirella wachtleri, dated to ~240 million years ago, is considered one of the oldest known squamates and resembles early lizards.

- Divergence of Lizards and Snakes (~200–180 million years ago, Early to Middle Jurassic)

Squamates split into lineages leading to lizards and snakes. While most lizards retained limbs, snakes later evolved limblessness. Early lizards developed diverse adaptations for specific niches—enhanced vision, specialized tongues, and varied locomotion methods for arboreal, terrestrial, and burrowing lifestyles.

- Major Radiation of Lizards (~150–100 million years ago, Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous)

Lizards diversified into major modern families like Iguanidae, Gekkonidae, and Scincidae. Continental drift and climate shifts created new habitats, driving adaptation to deserts, forests, and islands. Jurassic fossils like Eichstaettisaurus show early gecko-like traits developing during this crucial period.

- Cretaceous Diversification (~100–66 million years ago)

Lizards evolved specialized features like adhesive toe pads (geckos), color-changing skin (chameleons), and live birth (some skinks). These adaptations allowed them to thrive alongside dinosaurs and survive the mass extinction event. Chameleons and monitor lizards began appearing in recognizable forms.

- Post-Extinction Expansion (~66 million years ago to Present, Cenozoic Era)

After the K-Pg extinction eliminated non-avian dinosaurs, lizards filled vacant niches. Modern genera emerged, resulting in today’s 7,000+ species showcasing incredible variety—legless lizards, gliding lizards, and giant monitors. Paleocene and Eocene fossils reveal lizards resembling modern forms.

Where do Lizards live?

Lizards inhabit a wide range of environments across the globe, from arid deserts to lush rainforests. Their adaptability to diverse climates and terrains has allowed them to thrive on every continent except Antarctica. The following list highlights examples of lizards found in different regions and their unique adaptations to their habitats:

Africa:

Africa is home to a diverse range of lizard species, each uniquely adapted to its environment. The following examples highlight some of the fascinating lizards found on this continent and their distinctive traits:

- Agama Lizard (Agama agama): Often called the “African Rainbow Lizard,” this species is known for its vivid colors, especially in males, which can display a range of hues from blues and oranges to reds during breeding seasons.

- Armadillo Girdled Lizard (Ouroborus cataphractus): This small lizard from South Africa resembles an armadillo because of its unique defense mechanism: rolling into a ball and gripping its tail in its mouth to protect its underbelly from predators.

Asia:

Asia is home to a diversity of lizards, each uniquely adapted to its environment. The following examples highlight two iconic species that showcase the region’s rich ecological diversity and the fascinating adaptations of its lizard inhabitants:

- Komodo Dragon (Varanus komodoensis): The Komodo dragon is the largest living lizard, found on the Indonesian islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, and Gili Motang. They are apex predators known for their impressive size, growing up to 10 feet long and weighing over 150 pounds.

- Flying Gecko (Genus Ptychozoon): Flying geckos are found in Southeast Asia and have adapted flaps of skin along their limbs, sides, and tails that allow them to glide through the air, effectively jumping and steering between trees to escape predators or to catch prey.

Australia:

Australia is home to a diverse array of lizard species, each uniquely adapted to the continent’s varied landscapes, from arid deserts to tropical forests. The following are notable examples of lizards found in Australia and their traits:

- Tegu Lizards (Genus Tupinambis): Tegus are large, intelligent lizards known for their ability to regulate body temperature, in part through external means —a trait uncommon among reptiles.

- Monitor Lizards (Family Varanidae): The famous Perentie (Varanus giganteus), which can grow up to 2.5 meters in length, making it the largest lizard in Australia. These lizards are adaptable and can be found in a variety of habitats across the continent.

Europe:

Europe is home to several fascinating lizard species, each uniquely adapted to its environment. The following examples showcase some of the most notable lizards found across the continent and their distinctive characteristics:

- Ocellated Lizard (Timon lepidus): This is one of the largest European lizards, found in the Iberian Peninsula and parts of France and Italy. It sports a striking green or blue coloration with eye-like spots (ocelli) along its back, which gives it its name.

- European Green Lizard (Lacerta viridis): Found throughout southern Europe, this brightly colored lizard is known for its vivid green coloration, which can vary from turquoise to dark green.

What are the behaviors of Lizards?

Lizards display fascinating behaviors that highlight their adaptability and ecological success. These behaviors span a wide range of aspects, showcasing their evolutionary ingenuity in surviving and thriving in diverse habitats:

- Feeding strategies: Lizards exhibit diverse diets, ranging from insectivory and herbivory to predation on small mammals, and adapt hunting techniques such as ambush predation, active foraging, and sticky-tongue prey capture.

- Locomotion techniques: Their movement strategies include climbing with specialized toe pads, running on sand with splayed toes, and even burrowing or gliding, tailored to their specific environments.

- Defense mechanisms: Lizards employ tactics such as camouflage, tail autotomy, venomous bites, and threat displays, such as frill extensions, to evade or deter predators.

- Sensory adaptations: Advanced sensory systems include excellent color vision, the Jacobson’s organ for chemical detection, and specialized heat-sensing pits in certain species, enhancing their environmental awareness.

- Thermoregulation: As ectotherms, lizards rely on behaviors such as basking, burrowing, and seeking shade to regulate their body temperature.

- Reproductive strategies: With about 80% oviparous and 20% viviparous species, lizards demonstrate flexibility, from species laying numerous eggs to live-bearing adaptations in extreme environments.

First, let’s explore the feeding strategies of lizards and how they reflect their adaptability.

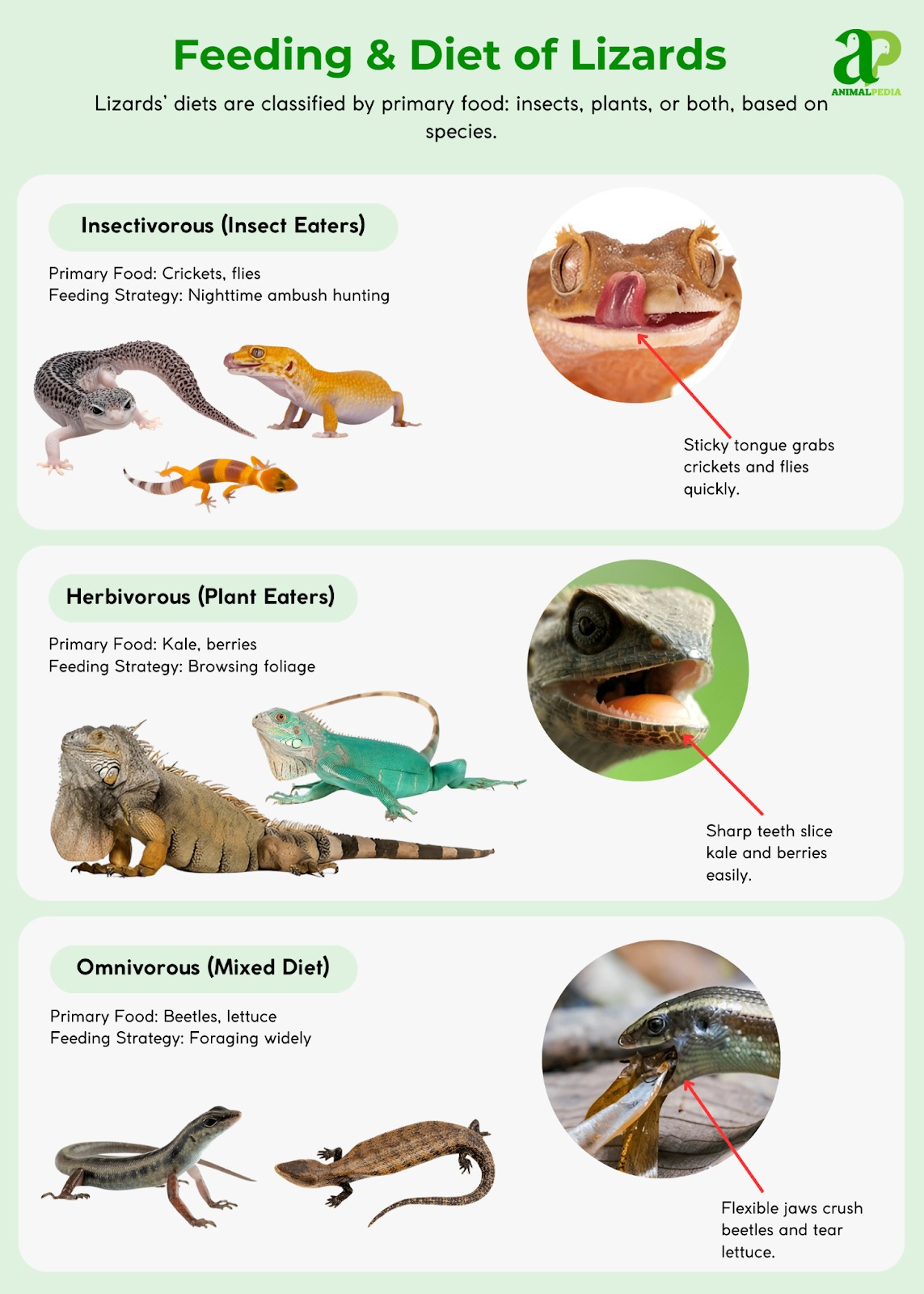

Diet & Feeding Strategies

The majority of lizards are carnivorous (especially insectivores), but there are also herbivorous and omnivorous species. Their diet depends on the species, size, habitat, and life stage. They usually eat small insects such as crickets, moths, and flies; fresh meat from large prey; and dark, leafy greens.

Their hunting techniques vary, including active foraging for prey, ambush predation (where they wait for unsuspecting victims), and using sticky tongues to capture insects. This versatility in feeding behaviors allows lizards to thrive in various ecosystems, showcasing their adaptability as predators and foragers.

Limbs and Locomotion

Lizards exhibit various limb adaptations and locomotion strategies, tailored to their specific environments and lifestyles.

Limbs and Locomotion:

- Short, Powerful Legs: Many desert-dwelling lizards have evolved short, stout legs that provide the burst of speed and power necessary for running across scorching sand. These legs are adept at quick, explosive movements, allowing lizards to dash to cover or chase down prey.

- Long, Slender Legs: Arboreal lizards, like many anoles, have long, slender legs that facilitate climbing and maneuvering through trees and bushes. Their longer, more flexible limbs allow greater reach and agility, which are essential for navigating complex vertical environments.

- Splayed Toes: Like fringe-toed lizards, certain species have developed splayed toes to aid in burrowing and running on loose sand. The expanded surface area of their toes prevents sinking and allows for efficient movement across unstable terrain.

- Specialized Pads: Some lizards, notably geckos, have toes equipped with specialized pads lined with microscopic hair-like structures known as setae. These setae exploit van der Waals forces to adhere to surfaces, enabling these lizards to climb smooth vertical walls and even traverse ceilings with ease.

Legless Lizards:

- Despite their appearance, legless lizards such as the European Legless Lizard, California Legless Lizard, and Eastern Glass Lizard are not snakes but belong to distinct lineages within the lizard family. They retain several lizard-like features, such as eyelids and external ear openings, which snakes lack. Moreover, many legless lizards have remnants of limbs or pelvic girdles, subtle indicators of their evolutionary heritage.

- The evolution of leglessness has occurred convergently multiple times across various lizard lineages, a testament to the adaptability of these reptiles. This adaptation allows them to burrow more effectively or navigate through dense underbrush with ease, demonstrating the diverse evolutionary strategies lizards have adopted to thrive in their environments.

Defense Mechanism

Camouflage is a common tactic many lizard species employ to blend into their surroundings. This passive defense allows them to avoid detection by predators, making it easier to escape unnoticed. The ability to match the color and texture of their environment can be sophisticated, providing an effective shield against predation.

Autotomy, or tail dropping, is another defense mechanism where a lizard voluntarily detaches its tail when threatened. The detached tail wiggles for a period, distracting the predator and allowing the lizard to escape. This process is an example of self-sacrifice for survival, as the lizard regrows its tail over time, though often smaller and less colorful. Threat displays are more active defense strategies that lizards use to deter predators. These can include puffing up their bodies to appear larger, hissing, or displaying bright colors.

A few lizard species have evolved venom as a defense mechanism. Notably, the Gila monster and the Mexican beaded lizard possess venomous bites that can be dangerous to humans and other predators. This venom is primarily used for defense rather than hunting, serving as a potent deterrent against larger threats.

Sensory Adaptation

Lizards exhibit a range of sensory adaptations that allow them to interact with their environment in sophisticated ways.

Eyesight:

- Lizards generally have good vision, with many species capable of perceiving colors, which helps them identify food, mates, and threats. Their eyes are equipped with movable eyelids and a nictitating membrane, a transparent third eyelid that helps protect the eye and keep it moist without obstructing vision.

- Nocturnal lizard species have eyes specialized for low-light conditions, allowing them to see effectively at night. These adaptations include larger pupils and a higher concentration of rod cells, which are more sensitive to light than cone cells.

Sense of Smell:

- The Jacobson’s organ is a specialized sensory structure in lizards, located in the roof of the mouth. Lizards use their tongue to collect chemical particles from the air or ground, which are then transferred to the Jacobson’s organ for analysis. This organ gives them a keen sense of smell to detect prey, predators, and potential mates.

Hearing:

- Unlike snakes, lizards have external ear openings, enabling them to detect airborne sound vibrations. This sense of hearing is beneficial for detecting the movements of predators or prey, although it is generally less developed than in mammals.

Other Senses:

- Heat-sensing pits: The Komodo Dragon has infrared-sensing pits on its face that allow them to detect the heat emitted by warm-blooded prey, even in total darkness.

- Specialized scales: Geckos have specialized scales that detect touch, pressure, and even environmental vibrations. This tactile sensitivity helps them navigate their habitats, detect prey, and communicate with other lizards.

Thermoregulation

Lizards, as ectotherms or “cold-blooded” animals, rely heavily on environmental heat sources to regulate their body temperature. Unlike endotherms, which can generate their heat internally, ectotherms depend on the sun’s warmth and the temperature of their surroundings to maintain the physiological processes necessary for survival. This reliance on external heat sources has led to various behavioral adaptations that allow lizards to regulate their body temperature effectively.

Lizards engage in thermoregulatory behaviors, such as basking in the sun, to warm up and boost their metabolism, which is crucial for activity and digestion. They seek shade during peak heat to avoid overheating and dehydration, maintaining an optimal temperature. Additionally, burrowing helps them escape extreme surface temperatures and predators, leveraging the more stable underground temperatures for warmth and cooling. These strategies are vital to their survival, enabling them to regulate body temperature effectively across a range of conditions.

How Do Lizards Reproduce?

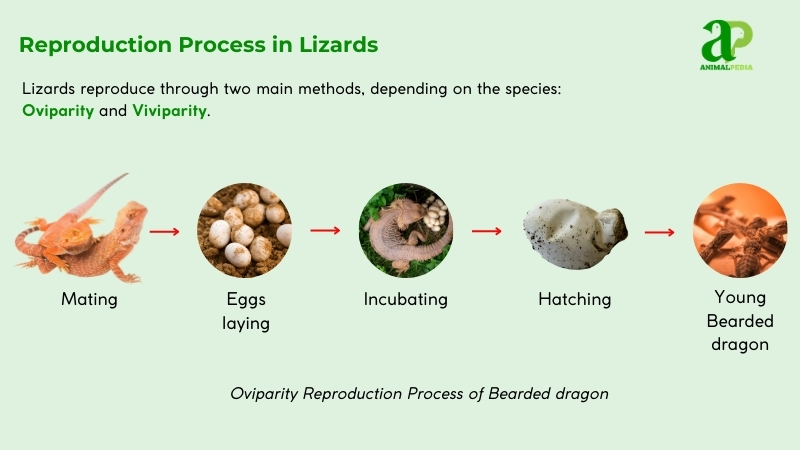

Lizards exhibit diversity in reproductive strategies, with about 80% oviparous (egg-laying) and 20% viviparous (live-bearing), and they adapt to diverse environments. This reproductive flexibility reflects millions of years of evolutionary refinement, as noted in recent herpetological studies.

Reproductive timing varies greatly among species. For example, the Green Iguana breeds in the dry season, laying 20-70 eggs after a 65-day gestation period. Meanwhile, the Common Wall Lizard breeds in spring, producing multiple clutches of 2-8 eggs. Uniquely, the Three-toed Skink can alternate between egg-laying and live births, depending on environmental conditions, showcasing an adaptive edge.

Courtship behaviors are intricate and species-specific, often involving displays such as head bobbing, push-ups, or vivid color changes by males to attract mates. After mating, oviparous females lay eggs in concealed locations, while viviparous species carry embryos internally until birth. Egg incubation generally lasts 30-60 days, depending on temperature.

Most lizards exhibit minimal parental care, but notable exceptions exist. The Great Desert Skink maintains elaborate burrows, providing protection for its offspring for weeks. Even more, the Solomon Island Skink demonstrates active parenting, with mothers carrying young in their mouths to shield them from predators and teaching foraging skills. These behaviors highlight the surprising complexity of lizard reproductive and parental strategies, even though such care is rare across the group.

What is the relationship between Lizards and Humans?

Lizards play a pivotal role in human life, offering significant contributions across various domains. From their deep-rooted cultural symbolism to their ecological and scientific importance, lizards have fascinated and benefited humanity in diverse ways:

- Culture and Mythology

Lizards hold significant roles in global cultural traditions, symbolizing wisdom, adaptability, and regeneration. In ancient Egypt, they represented good fortune, while Native American cultures viewed them as symbols of survival. The god Sobek, depicted as a crocodile-headed deity, embodied Nile fertility, showing the reverence these reptiles commanded. In Asian traditions, lizards were believed to ward off misfortune, their regenerative ability making them powerful symbols of renewal and growth.

From Australian Aboriginal creation myths where lizards act as tricksters or fire-bringers to European folklore considering them omens of fortune, lizards permeate our collective imagination. Modern pop culture continues this fascination through characters like Godzilla, reflecting our complex relationship with nature’s power. In cartoons and video games, lizards appear as wise companions or formidable adversaries, their ancient symbolism of wisdom and adaptability resonating through contemporary media.

- Resources

Lizards have played significant roles in human culture as both biological resources and material goods. Various cultures have historically harvested lizards for food, providing a valuable source of protein in regions with limited meat sources. Their bodies, especially larger species, have also been incorporated into traditional medicine systems worldwide, believed to treat conditions ranging from respiratory problems to joint pain, despite limited scientific validation.

Additionally, lizard skin has been prized for its distinctive patterns and durability, becoming a coveted material in luxury leather goods production. The commercial value of species like monitors and tegus has created substantial markets for belts, shoes, and accessories. While some sustainable harvesting programs exist today, conservation concerns have led to international trade regulations that balance human use with protection of vulnerable populations, especially as habitat loss threatens many lizard species worldwide.

- Scientific Study

Lizards are valuable subjects for scientific research, contributing to our understanding of evolution, adaptation, and regenerative biology. Their diverse traits and behaviors provide insights that advance both biological and medical sciences. From studies on Galápagos marine iguanas revealing environmental adaptation, to research on Anolis lizards demonstrating evolutionary dynamics in urban settings. This famous genus also includes some of the most striking examples of island speciation, such as the rare Blue Anole. These reptiles offer unique perspectives on natural selection.

The regenerative abilities of lizards are among the most fascinating areas of research. Many species can regrow lost tails, a capability that has captured the attention of medical researchers worldwide. By studying the cellular and molecular mechanisms behind this tissue regeneration, scientists hope to develop new therapeutic approaches for human medicine, potentially leading to breakthroughs in treating injuries and degenerative conditions that currently have limited treatment options.

- Pets

Lizards are increasingly popular as exotic pets, particularly leopard geckos and bearded dragons, prized for their manageable care requirements and docile nature. Caring for these pets demands a commitment to replicating their natural habitat, focusing on specific needs such as diet, temperature gradients, and appropriate lighting.

Ethical ownership is crucial, involving responsible sourcing to avoid supporting the illegal wildlife trade and understanding the commitment to their long-term well-being. It also includes preventing the release of non-native species to avoid ecological impacts.

Are Lizards going to become endangered?

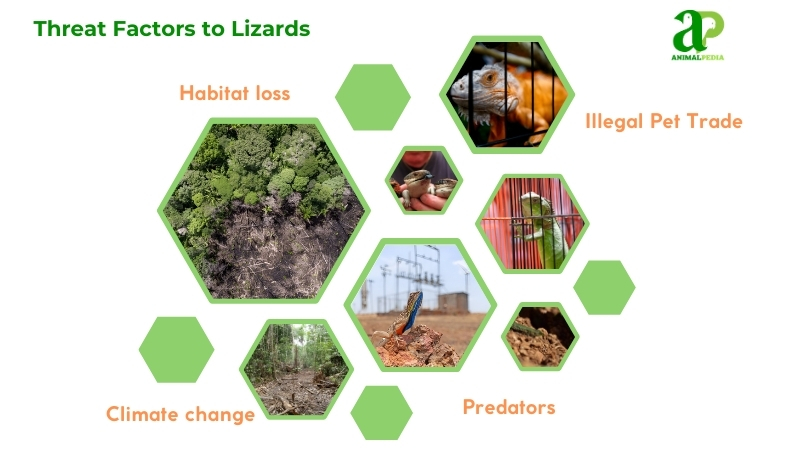

Yes, lizards face growing threats in today’s rapidly changing environment. A study by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) found that approximately 20% of reptiles, including lizards, are threatened with extinction.

In the modern world, lizards face significant challenges that threaten their survival, with specific examples highlighting the gravity of these threats:

- Habitat Loss: The deforestation in the Amazon affects countless species, including the diverse lizard populations that depend on this vast ecosystem for survival.

- Climate Change: The increasing temperatures and altered weather patterns severely impact the Galápagos marine iguanas, as rising sea levels and temperature changes affect their food sources and nesting sites.

- Illegal Pet Trade: Species such as the critically endangered Tokay Gecko are heavily impacted by the trade, with their populations declining due to overcollection for pets and traditional medicine.

Global conservation efforts are working to safeguard these creatures. In New Zealand, 83% of native lizard species are under active conservation programs, highlighting the nation’s dedication to conservation. Success stories like the Chinese Crocodile Lizard (Shinisaurus crocodilurus) and the Sri Lankan Leaf-nosed Lizard showcase how international partnerships and relocation initiatives have positively impacted at-risk species.

Conservation strategies involve multiple approaches. Protected areas, such as New Zealand’s predator-free islands and Southeast Asian rainforest reserves, shield critical habitats. The CITES convention has bolstered enforcement against illegal wildlife trafficking, targeting the exotic pet trade. Captive breeding programs also play a vital role in species recovery, while education campaigns reduce human impact. For instance, Argentina’s Liolaemus lizard conservation project integrates habitat restoration with community engagement, demonstrating the effectiveness of holistic approaches.

How does Lizard affect humans and the environment?

While lizards generally benefit ecosystems, certain scenarios result in negative environmental and societal impacts. Invasive lizard species, such as the Anolis lizard, disrupt native ecosystems by outcompeting local species and altering food webs, as highlighted in Biological Conservation (2020). In agricultural regions, lizards can accumulate pesticides in their tissues, posing risks to wildlife and human food chains when predators consume them.

Cultural misconceptions about lizards further exacerbate their decline. Negative beliefs in some regions lead to unnecessary killings, disruptingthe ecological balance. A study in the Journal of Ethnobiology (2018) noted that these misconceptions significantly harm lizard populations.

Solutions to these challenges are proving effective. Habitat restoration programs, such as the Australian Lizard Conservation Program, have revitalized over 1,000 hectares of critical habitat, boosting native lizard populations by 40%. Sustainable agriculture initiatives have reduced pesticide use in lizard-rich areas, fostering healthier ecosystems.

Community education programs are crucial in changing perceptions, reducing intentional killings, and encouraging conservation. Invasive species management, including early detection and rapid response protocols, has also successfully safeguarded native lizard populations globally. These efforts demonstrate that targeted strategies can mitigate threats and support lizard conservation.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does a lizard’s tail help it survive?

A lizard’s tail serves multiple survival functions. It can serve as a fat storage site, helping the lizard survive during periods of food scarcity. In instances of predation, many lizard species can detach their tails (autotomy) to distract predators and escape. The tail also plays a role in communication and mating rituals for some species.

Why do lizards have such varied scale patterns?

The varied scale patterns on lizards serve several purposes, including camouflage, thermoregulation, and sexual selection. Camouflage helps lizards blend into their environment to avoid predators and ambush prey. Different scale patterns can also facilitate heat absorption or reflection, aiding in thermoregulation.

How do some lizards run on water?

The basilisk lizard, also known as the “Jesus Christ lizard,” can run on water thanks to its unique foot structure and rapid stride. Its feet have flaps of skin that unfurl when striking the water, increasing surface area and creating a pocket of air that keeps them from sinking. Coupled with their lightweight bodies and swift movements, these lizards can dash across water surfaces for short distances without submerging.

Which lizards make popular pets, and why?

Leopard geckos and bearded dragons are among the most popular pet lizards due to their manageable size, docile nature, and relatively simple care requirements. Leopard geckos are nocturnal, known for their vibrant colors and patterns, and don’t require UV lighting. Bearded dragons are diurnal, friendly, and often enjoy human interaction, making them excellent companions.

How are human activities threatening lizard populations?

Human activities pose significant threats to lizard populations through habitat destruction, climate change, pollution, and the illegal pet trade. Urban development, agriculture, and deforestation result in habitat loss and fragmentation, making it difficult for lizards to find food, mates, and shelter. Climate change alters their habitats and can disrupt breeding cycles and food availability. Pollution affects their health and the ecosystems they depend on.

Lizards represent one of evolution’s most successful stories, thriving for over 250 million years through continuous adaptation. With more than 7,000 species displaying incredible diversity in form and function, they’ve colonized nearly every habitat on Earth except Antarctica. Their ecological significance is immense as insect controllers, prey, and contributors to biodiversity. However, many species now face unprecedented threats from habitat destruction, climate change, and human activities. Conservation efforts have shown promising results, highlighting the importance of protecting these ancient reptiles. By understanding lizards’ evolutionary journey and ecological roles, we gain valuable insights into nature’s resilience.