Marine iguanas stand alone among lizards—the single species Amblyrhynchus cristatus. These remarkable reptiles, commonly called “sea iguanas,” display dark colors—black, gray, or reddish after feeding on algae. Endemic to the Galápagos archipelago, they inhabit islands from Fernandina to Española. Their most striking feature? Size. Adults reach 2-4 feet (60-120 cm), with males growing larger and displaying prominent dorsal crests that evoke prehistoric times.

These specialized lizards dominate the volcanic coastlines, thriving where few reptiles could survive. Their geographic distribution is limited to specific Galápagos islands—notably Isabela and Santa Cruz. They prefer rocky shores and intertidal zones. Here they bask on lava formations, absorbing heat after cold ocean dives. This ecological niche remains uniquely theirs.

Marine iguanas are not predators but specialized herbivores. They dive—sometimes 30 feet (9 meters) deep—to harvest algae from submerged rocks. Their blunt snouts and razor-sharp teeth perfectly scrape this marine vegetation. They hunt alone, never chasing prey. Human encounters? Minimal impact. When threatened, they retreat, expelling salt through specialized nasal glands—an effective defense mechanism.

Reproduction begins in December, peaking from January through March. Females deposit 1-6 eggs in sandy nesting burrows, dug deep to maintain temperature. Incubation lasts 90-120 days before hatchlings emerge, immediately facing predation from crabs and birds. Young iguanas grow rapidly, reaching sexual maturity in 3-5 years. Their lifespan ranges from 5-12 years, though some individuals survive longer in this harsh environment.

This examination of Amblyrhynchus cristatus covers physical characteristics, habitat requirements, and behavioral patterns. It explores their unique Galápagos existence, from marine foraging to reproductive challenges, presenting scientific facts with natural authenticity.

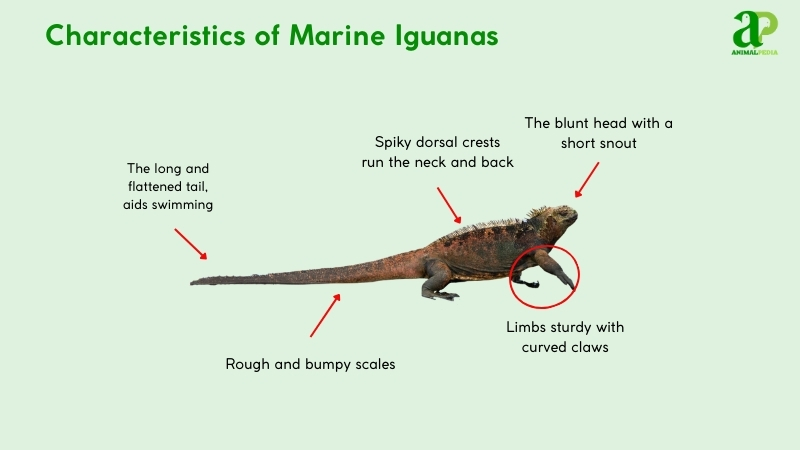

What Do The Marine Iguanas Look Like?

Marine iguanas have powerful, flat bodies measuring 2-4 feet long. Their dark coloration—primarily black or gray—may show reddish tints after feeding on algae. Rough scales cover their skin, creating a wrinkled texture perfect for gripping volcanic rocks.

Their blunt heads feature short snouts, small alert eyes, and flicking tongues. Spiny crests run along their necks and backs. Strong limbs with curved claws help them navigate both land and sea. Their flattened tails function as swimming paddles, essential for marine mobility.

Unlike their land-dwelling relatives (Conolophus), marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) lack bright greens or yellows. Their camouflage coloring blends with Galápagos lava formations. Their specialized salt-excreting nostrils expel excess salt—a unique adaptation absent in terrestrial species.

Their underwater vision surpasses that of land iguanas, while their tail and claw structure enables efficient swimming at speeds up to 1 mph. These endemic reptiles represent textbook examples of evolutionary adaptation, with bodies perfectly designed for their amphibious lifestyle on the volcanic shores of the Galápagos archipelago.

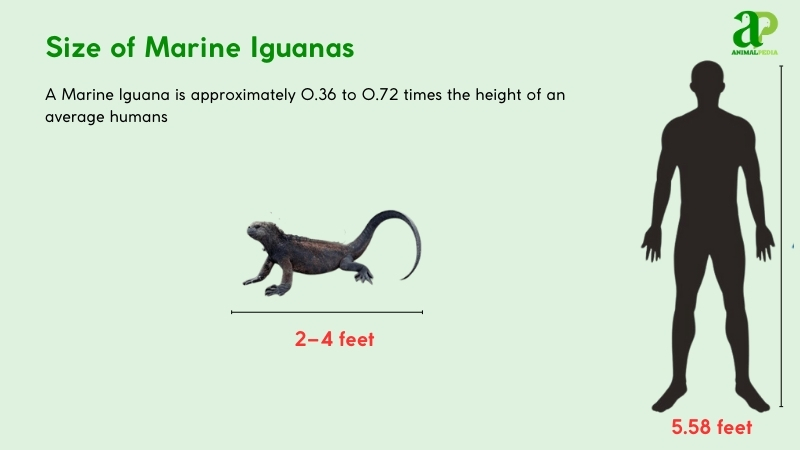

How Big Do Marine Iguanas Get?

Marine iguanas average 2-4 feet (0.6-1.2 meters) in length and weigh 1-3 pounds (0.5-1.5 kg). Males outsize females, hitting the upper end, while females hover at the lower. Adults typically reach 3 feet (0.9 meters) from snout to tail, though size varies by island.

The largest recorded specimen, found on Isabela Island, stretched 4.6 feet (1.4 meters) and tipped 11 pounds (5 kg), per a 2017 study by Nelson et al. in Herpetological Review.

Sexual dimorphism shapes their size. Males, heavier and longer, boast dorsal spines and bulk for dominance. Females, leaner, prioritize agility. Research shows males average 3.5 feet (1.1 meters) and 3 pounds (1.4 kg), females 2.5 feet (0.8 meters) and 1.5 pounds (0.7 kg). See the table below for clarity.

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 3.5 – 4 ft ( 1.1 – 1.2 m) | 2.5 – 3 ft ( 0.8 – 0.9 m) |

| Weight | 3 lbs ( 1.4 kg) | 1.5 lbs (0.7 kg) |

What Are The Unique Physical Characteristics Of The Marine Iguanas?

Marine iguanas possess unique adaptations found in no other lizard species. Their specialized nasal glands sit on top of their heads, efficiently expelling excess salt from seawater—a remarkable evolutionary feature uncommon among reptiles. Their skin coloration changes from black to reddish after feeding, directly linked to their algae consumption. The flattened, laterally compressed tail distinguishes them from land iguanas, enabling powerful swimming.

These Galápagos endemics (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) have evolved sharp dorsal spines and blunt snouts perfectly suited for their harsh environment—navigating volcanic rocks and cold ocean waters. Research by Berger et al. (2020) documents how their salt excretion mechanism works through distinctive snorting, a direct adaptation to marine life. Their powerful tails propel them to depths of 30 feet (9 meters) underwater, a diving capability unmatched by their terrestrial relatives, as confirmed in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

The pigmentation shifts observed in these reptiles reflect carotenoid absorption from red algae consumption, serving as visual indicators of health status. Their rigid, elongated spines provide crucial stability on wet, slippery coastal rocks. Each of these specialized features—salt glands, swimming tail, color-changing ability, and protective spines—represents the perfect fusion of evolutionary adaptation and survival strategy, making marine iguanas true outliers in the reptilian world.

How Do Marine Iguanas Adapt With Its Unique Features?

Marine iguanas thrive in the wild thanks to standout traits. Salt-excreting nasal glands flush seawater sodium, letting them feed on marine algae without dehydration. Flattened tails propel them 30 feet (9 meters) underwater, securing food from rocky depths. These Galápagos natives cling to volcanic shores, their rugged scales gripping lava.

Other senses bolster this survival. Keen eyes spot algae patches, aiding foraging in murky waters. Sharp claws dig into rocks, stabilizing them against waves. Sensitive skin detects temperature shifts, guiding basking to rewarm after dives. A flicking tongue samples air, alerting them to predators. Together, these traits fuse form and function for oceanic life.

Anatomy

Marine iguanas, the only ocean-swimming lizards on Earth, have evolved extraordinary internal systems to thrive on the volcanic shores of the Galápagos Islands. Every organ system is tuned to the demands of their unique habitat—icy waters, wave-battered rocks, and algae-based diets.

- Respiratory System: Enlarged lungs store air for up to 30-minute dives. Oxygen efficiency supports extended foraging beneath the waves.

- Circulatory System: Heart rate slows to as low as 9 beats per minute during submersion, redirecting blood to vital organs and preserving warmth in cold waters.

- Digestive System: Blunt snouts and tricuspid teeth shred algae. A long intestinal tract slowly ferments seaweed for maximum nutrient extraction.

- Excretory System: Specialized nasal salt glands excrete excess sodium from ingested seawater, preventing dehydration.

- Nervous System: Acute vision, especially underwater, and rapid tongue flicks detect algae patches and potential threats. Reflexes help them escape predators on rugged terrain.

Together, these systems form a finely tuned biological machine. From respiration to reflex, marine iguanas embody evolutionary precision—built to endure and excel where few reptiles dare to roam.

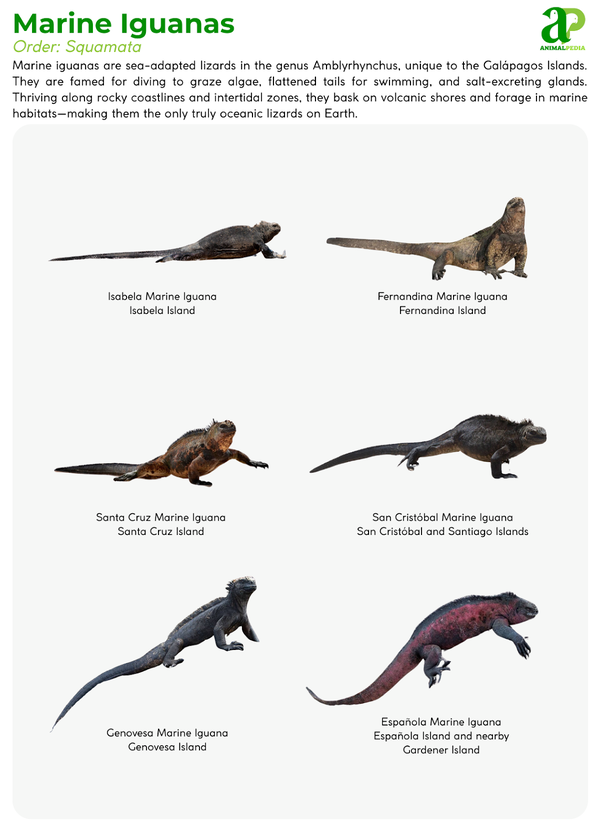

How Many Types Of Marine Iguanas?

Marine iguanas, whose scientific name is Amblyrhynchus cristatus, are a monotypic species, meaning they are the only living species in the genus Amblyrhynchus, within the family Iguanidae. However, they are divided into at least 11 genetically distinct populations or subspecies (around 6-7 marine iguana subspecies are popular and easy to recognize), each isolated on different Galápagos Islands, exhibiting slight variations in size, coloration, and behavior.

Classification follows the Linnaean taxonomy system, developed by Carl Linnaeus, and refined using both morphological traits and molecular genetics. Recent phylogenetic research has confirmed distinct population structures shaped by island biogeography and natural selection.

Order: Squamata

└── Family: Iguanidae

└── Genus: Amblyrhynchus

└── Species: Amblyrhynchus cristatus

A special case within this taxonomy involves localized subspecies (e.g., A. c. godzilla on San Cristóbal Island), which may warrant species-level distinction pending further genomic analysis. These divergences highlight the effects of adaptive radiation and allopatric speciation in island ecosystems (MacLeod et al., 2015).

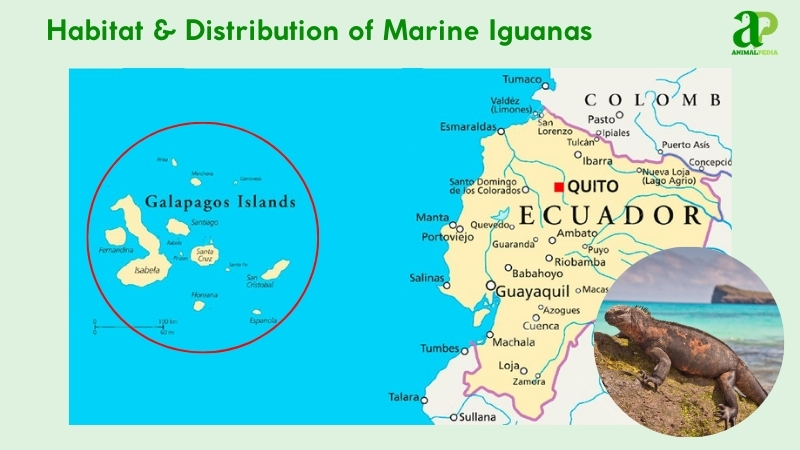

Where Do Marine Iguanas Live?

Marine iguanas inhabit the Galápagos Archipelago, located in the eastern Pacific Ocean about 600 miles off Ecuador’s coast. They primarily occupy the coastal zones of Fernandina, Isabela, Santa Cruz, and Española islands. Rocky shores and lava fields form their natural territory. Each island hosts distinct subspecies adapted to local environmental conditions.

Their ecosystem features volcanic substrates, cold Humboldt currents, and rich algal beds – creating ideal conditions for these unique reptiles. Sun-baked coastlines provide essential warmth after cold-water feeding dives, while nutrient-dense waters support abundant macroalgae, their primary food source. This environment perfectly complements their specialized salt-excretion glands and laterally-compressed tails evolved for marine survival.

These endemic reptiles have occupied the Galápagos for millions of years without migration elsewhere. Phylogenetic studies and fossil evidence analyzed by Nelson and colleagues (2017) indicate they descended from mainland iguana ancestors that rafted to the islands on floating vegetation. Geographic isolation drove their evolution into the world’s only marine lizards, permanently binding them to their volcanic island home.

How Do Seasonal Changes Affect Their Behavior?

Marine iguanas display remarkable seasonal adaptability, shaped by the Galápagos’ harsh and fluctuating climate. Their behavior shifts in response to two distinct periods:

- Wet Season (Dec–May): Warmer seas stimulate algae blooms. Iguanas dive frequently, feeding to build reserves. Males engage in intense territorial displays as mating peaks.

- Dry Season (Jun–Nov): Cold currents reduce algae. Iguanas bask for warmth and limit movement. Remarkably, they shrink their body size by up to 20% to survive.

This reversible size change—rare among vertebrates—highlights their physiological plasticity. As Berger et al. (2020) revealed, marine iguanas’ survival hinges on synchronized behavioral and metabolic adjustments in a volatile ecosystem.

What Is The Behavior Of Marine Iguanas?

Marine iguanas exhibit unique behaviors shaped by their Galápagos home. These reptiles balance survival with an oceanic twist, showcasing distinct habits.

- Feeding Habits: They dive up to 30 feet (9 meters) to graze algae. It’s their sole diet, scraped with sharp teeth.

- Bite & Venomous: No venom here—just a mild bite if threatened. They’re harmless to humans, preferring flight over fight.

- Daily Routines: Mornings mean basking on rocks; afternoons, diving for food. Energy conservation drives their slow pace.

- Locomotion: They swim with flattened tails, crawl with sturdy limbs. Speeds hit 1 mph (1.6 kph) in water.

- Social Structures: Mostly solitary, males turn territorial in mating season. Groups bask together but don’t bond.

- Communication: Salt snorts and head bobs signal warnings. Visual cues dominate their sparse chatter.

These quiet creatures thrive through timing, energy control, and aquatic finesse—true masters of island life. Curious about their meals? Let’s dive deeper into feeding habits next.

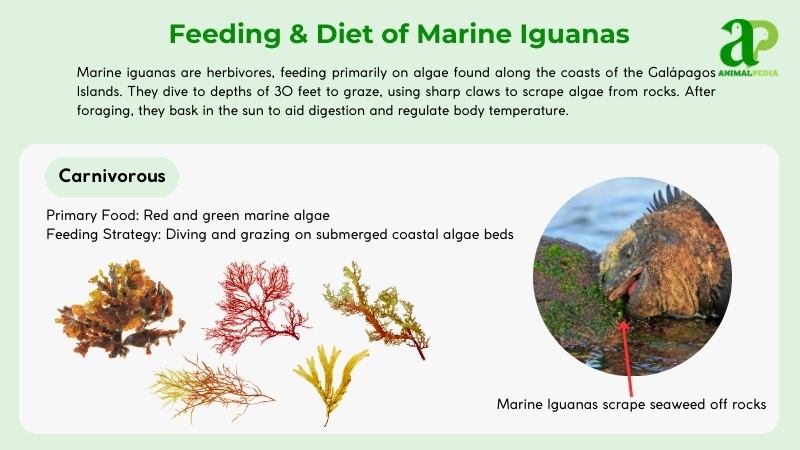

What Do Marine Iguanas Eat?

Marine iguanas are strict herbivores, subsisting almost entirely on marine algae. Marine Iguanas’ diet and foraging patterns shift based on age, body size, and seasonal algae availability. Adapted to harsh coastal environments, they are the only lizards that forage in the ocean.

- Diet by Age

Hatchlings and juveniles feed primarily in the intertidal zone, where algae are accessible without deep diving. Their small body size and lower energy demands suit this limited foraging range. As adults, marine iguanas—especially larger males—dive deeper (up to 9 meters) to reach submerged algae beds rich in Ulva and Gracilaria. They develop strong claws and flattened tails to aid underwater feeding.

- Diet by Gender

Males and females eat the same algal species, but males often dive more frequently and forage in deeper waters. This is driven by their larger size and territorial behavior during the mating season, which increases energy demands. However, there is no distinct difference in foraging technique between sexes.

- Diet by Seasons

In the wet season (December–May), warmer waters boost algae growth, leading to more frequent and longer dives. During the dry season (June–November), cold currents reduce algae availability. Iguanas feed less, lose body mass, and spend more time basking to conserve energy (Berger et al., 2020).

How Do Marine Iguanas Hunt Their Prey?

Marine Iguanas aren’t hunters in the traditional sense. These herbivorous reptiles feed exclusively on marine algae and seaweed in the Galápagos ecosystem. They dive into cold Pacific waters, using their powerful tails to propel through ocean currents with remarkable efficiency.

Specialized feeding occurs when they reach submerged rocks. Marine Iguanas use their uniquely adapted blunt snouts and sharp teeth to scrape algae from volcanic surfaces. Their teeth function like effective tools, removing plant material that clings to underwater formations.

While appearing lethargic on land, these ectothermic lizards transform underwater. They can hold their breath for up to 30 minutes during foraging dives that reach depths of 15 meters. Their salt glands expel excess sodium through distinctive “sneezing” after feeding sessions.

The Amblyrhynchus cristatus has evolved specific adaptations for this marine grazing. Their flattened tails provide swimming power, while their dark coloration absorbs solar radiation to counter the thermal challenges of cold water immersion. Their digestive microbiome processes tough algal material other animals cannot utilize.

This specialized feeding strategy maintains the ecological balance of Galápagos marine environments by regulating algae populations. During El Niño events, when food becomes scarce, these remarkable creatures can actually shrink their skeletal structure to survive – a response unique among vertebrates.

Are Marine Iguanas Venomous?

Marine Iguanas lack venom. These Galápagos reptiles use sharp teeth only to graze on algae and seaweed.

Their most remarkable feature is specialized salt-excreting glands near their nostrils. These glands filter excess sodium from their bloodstream, allowing them to thrive in saltwater environments while feeding on marine vegetation. The expelled salt often appears as white residue on their heads.

Amblyrhynchus cristatus – their scientific name – are exceptional divers. They plunge to depths of 30 feet, where they scrape algae from submerged rocks. Their thermoregulation abilities let them survive both cold ocean waters and hot volcanic rocks. Their black coloration helps absorb heat quickly after cold ocean dives.

Though lacking venom, these marine-adapted ectotherms possess physiological adaptations unmatched by other lizard species. Their specialized claws, flattened tails for swimming, and blunt snouts for efficient algae harvesting make them perfectly suited to their unique ecological niche in the harsh Galápagos archipelago.

When Are Marine Iguanas Most Active During The Day?

Marine Iguanas are most active during the day, with their peak activity occurring in the mornings. At this time, you can often see them sunbathing on rocks or sandy shores to warm up their bodies.

As the day progresses and the sun gets higher, Marine Iguanas become more active and start foraging for food along the coastlines or in shallow waters. One of the fascinating sights is watching them dive into the water to feed on underwater algae, their primary food source.

After a busy day of feeding and swimming, Marine Iguanas typically return to their favorite sunbathing spots to rest and regulate their body temperature. This daily routine helps them thrive in their coastal habitats and adapt to their unique environment.

How Do Marine Iguanas Move On Land And Water?

Marine Iguanas exhibit a fascinating mix of behaviors both on land and in water as they navigate their coastal habitats. These remarkable creatures show remarkable adaptability, effortlessly transitioning between their terrestrial and aquatic environments. On land, they showcase impressive agility by using their robust limbs to move across rocks and sandy shores in search of food or a sunny spot to soak up warmth. Whether swiftly darting or delicately perching on rugged surfaces, their exceptional balance is evident.

However, it’s in the water where Marine Iguanas truly shine. These adept swimmers glide through the ocean with ease, using powerful tail strokes to propel themselves forward. Their movements underwater are captivating, displaying grace and fluidity as they navigate their marine realm.

Whether gracefully swimming along the ocean floor or elegantly surfacing for air, Marine Iguanas move with efficiency and beauty, a testament to their incredible adaptation to living both on land and in the sea. Witnessing these creatures in their element is a true marvel of nature’s ingenuity.

Do Marine Iguanas Live Alone Or In Groups?

Although they’re typically solitary creatures, Marine Iguanas can gather in large groups, especially during breeding seasons or in areas with abundant resources. These gatherings are mainly for enhancing foraging efficiency and protection against predators rather than socializing. Within these groups, individuals may display dominance behaviors as they establish territories.

The choice to live alone or in groups varies for these intriguing creatures, showcasing their adaptable nature crucial for survival. They possess the freedom to adjust their social interactions based on current needs, demonstrating remarkable flexibility in behavior patterns. Understanding how Marine Iguanas communicate and navigate their dynamic social environment provides insight into their fascinating lifestyle.

How Do Marine Iguanas Communicate With Each Other?

Marine Iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) use clear non-verbal signals in their Galápagos coastal habitats. They rely on physical displays and body language to convey messages within their colonies. During territorial disputes, these reptiles bob their heads, inflate their bodies, or engage in ritual biting to establish dominance hierarchies or defend territory.

For reproductive signaling, male iguanas undergo dramatic chromatic transformation. Their skin displays vibrant pigmentation – striking reds and greens that indicate breeding readiness. This visual communication serves as a powerful courtship display.

Females communicate receptiveness through subtle postural changes or permitting closer proximity without displaying threat behaviors.

Beyond visual signals, these endemic reptiles employ chemical communication. They deposit pheromone markers throughout their environment to establish territorial boundaries, warn of predator presence, or attract potential mates during breeding season.

This sophisticated multi-channel communication system reveals the complex social structure and adaptive behaviors that characterize Amblyrhynchus cristatus populations in their natural ecosystem.

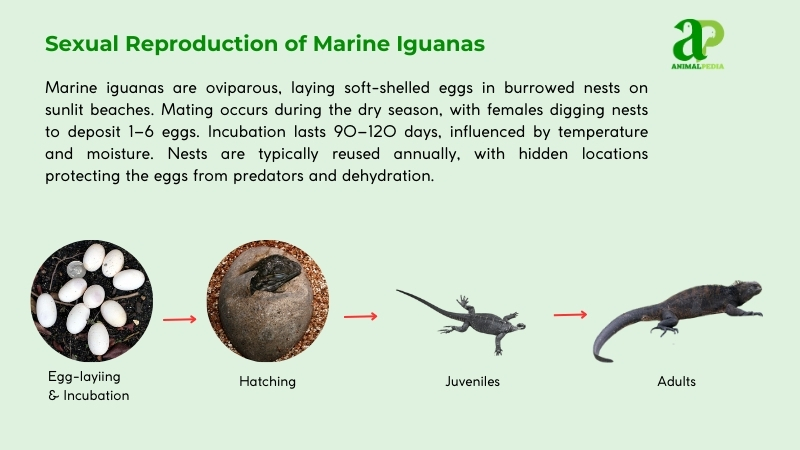

How Do Marine Iguanas Reproduce?

Marine iguanas reproduce sexually, laying eggs in a process shaped by island ecology.

Breeding season begins in December and peaks through March—during the wet season. Males transform dramatically, their bodies flushing with vibrant red coloration. They establish territories through head-bobbing displays and physical contests. Females select successful males, mating on coastal rocks. The copulation is brief but effective—tails align for precise sperm transfer.

After mating, females deposit 1-6 eggs weighing approximately 3 ounces (85 grams) each, as documented by Nelson et al. (2017). They excavate nesting burrows in sandy substrate, typically 1-2 feet (30-60 cm) deep. Unlike some reptiles, marine iguanas practice no parental care—females abandon nests after laying. Males depart immediately post-copulation. El Niño events can inundate nesting sites, as observed in 2016, causing significant reproductive failure.

Incubation spans 90-120 days. Hatchlings emerge measuring 9 inches (23 cm), immediately facing predation from crabs and hawks. Juveniles develop rapidly, reaching sexual maturity between 3-5 years, adopting the characteristic algae-grazing behavior of the species.

The lifespan of Amblyrhynchus cristatus typically ranges from 5-12 years, with exceptional individuals reaching 20. Environmental stressors, particularly nutritional scarcity and climate fluctuations, can significantly impact longevity and reproductive success.

How Long Do Marine Iguanas Live?

Marine iguanas have an average lifespan of 12 years, though some individuals may live up to 20 years in the wild under optimal conditions. Survival rates vary by island, population density, and environmental pressures like El Niño events, which can dramatically reduce food availability.

Males and females generally share similar lifespans, but larger males, due to higher energetic costs from territorial behaviors, may experience slightly shorter longevity (Wikelski & Trillmich, 2020). Predation and habitat changes can also influence longevity across subpopulations.

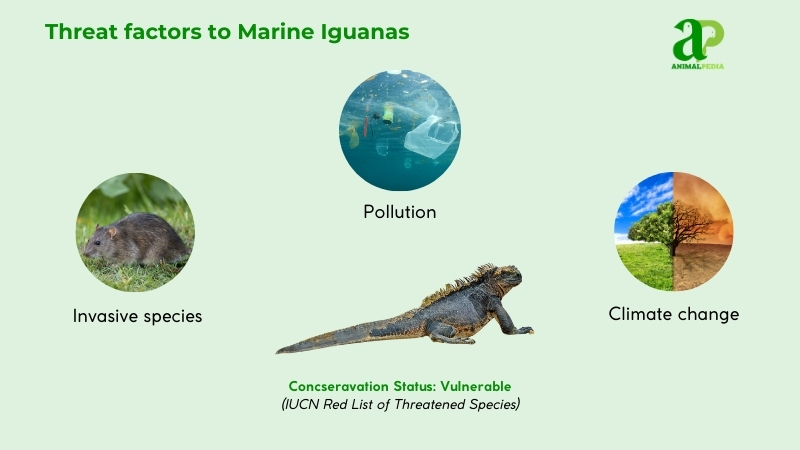

What Are The Threats Or Predators That Marine Iguanas Face Today?

Marine iguanas battle a gauntlet of threats and predators in the Galápagos. Climate change, invasive species, and human activity top the list, while natural hunters stalk their young.

Threats hit hard:

- Climate Change: El Niño floods drown nests, slashing hatchling survival by 80% (Nelson et al., 2017). Warming seas shrink algae stocks.

- Invasive Species: Rats and cats, brought by humans, are marine iguana enemies that raid eggs and juveniles. Populations on some islands drop 30% from these pests.

- Pollution: Oil spills coat shores, poisoning iguanas and food. Recovery lags years behind each spill.

There are also threats coming from Marine iguana predators that only target the vulnerable. Hawks (Buteo galapagoensis) snatch hatchlings fresh from eggs. Crabs and snakes grab stragglers on rocky beaches. Adults, armored by size, dodge most attacks—juveniles bear the brunt.

Humans amplify the mess. Tourism tramples habitats; boats spill fuel. Berger et al. (2020) found a 20% body size drop linked to food loss from human-driven shifts. Fishing nets tangle iguanas, and plastic chokes their guts. Conservation lags, but awareness grows—still, the clock ticks.

Are Marine Iguanas Endangered?

Marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) are vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Some subspecies face more severe threats, with classifications of Endangered or Critically Endangered (IUCN, 2020).

These reptiles exist only in the Galápagos archipelago, making them particularly susceptible to ecological disturbances. Predation by non-native species—feral cats, dogs, and rats—significantly reduces hatchling survival. El Niño events severely limit the algal food sources these iguanas depend on, causing population crashes and physiological adaptations including body shrinkage.

Population estimates range from 200,000 to 300,000 individuals across 13 major islands and numerous islets (Romero et al., 2020). Distribution varies considerably, with certain island subpopulations showing alarming declines due to anthropogenic impacts, marine debris, and water contamination.

Environmental threats such as oil spills—like the 2001 San Cristóbal incident—and expanding tourism infrastructure continue to degrade crucial coastal habitats needed for both nesting and feeding activities.

What Conservation Efforts Are Underway?

Marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) benefit from focused conservation across the Galápagos archipelago. The Galápagos National Park Directorate (GNPD) and Galápagos Conservancy lead these efforts, which have intensified since 2015. These organizations protect critical habitats and reduce threats from non-native predators.

Ecuadorian law provides strict protection. The species appears in CITES Appendix II, blocking international trade. Local regulations forbid hunting, habitat damage, and introducing predators. Campaigns target feral cats and rats for removal. Coastal road speed limits protect hatchlings from vehicle strikes.

Breeding protection programs show results. The GNPD eliminated black rats from Pinzón Island by 2012, dramatically improving hatchling survival rates. While no formal captive breeding exists for marine iguanas, strategies borrowed from land iguana conservation prove effective. Research by Nelson et al. (2017) estimates the population at 200,000-300,000 individuals, remaining stable despite El Niño disruptions.

The “Iguanas from Above” initiative, a partnership between Leipzig University and the Galápagos Conservation Trust launched in 2019, uses drone technology for population surveys. Their 2023 count documented 9,308 iguanas on Española Island, validating non-invasive monitoring techniques.

Key conservation partners include the Charles Darwin Foundation, which drives research initiatives, and the International Iguana Foundation, which funds plastic pollution studies. Success appears in places like Playa de los Perros on Santa Cruz Island, where GNPD data shows population stabilization by 2020 after seven years of ranger monitoring. This combination of legislation, technology, and field conservation sustains the species.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do Marine Iguanas Have Any Unique Adaptations For Survival?

Yes, marine iguanas have unique adaptations for survival. They possess specialized nasal glands that help them expel excess salt ingested while feeding on seaweed. This adaptation allows them to thrive in their harsh marine environment.

Are Marine Iguanas Affected By Climate Change?

Yes, marine iguanas are affected by climate change. Rising temperatures impact their food supply, causing stress and population declines. Adaptation is pivotal for survival. Protecting their habitats and reducing carbon emissions can help these unique creatures thrive.

How Do Marine Iguanas Communicate With Each Other?

To communicate, marine iguanas use a combination of head bobs, body postures, and vocalizations. These signals convey messages about territory, courtship, and threats. By observing their behaviors closely, you can decipher the nuances of their interactions.

Can Marine Iguanas Adjust To Different Water Salinities?

Yes, marine iguanas can adjust to varying water salinities to survive. They possess specialized salt glands near their noses to expel excess salt ingested while feeding on marine algae. This unique adaptation allows them to thrive in various coastal environments.

Do Marine Iguanas Have Any Cultural Significance To Local Communities?

Yes, marine iguanas have cultural significance to local communities. They are revered for their resilience and unique connection to the sea. Understanding their behavior and adaptation strategies enriches local traditions and fosters environmental stewardship among communities.

Conclusion

Marine iguanas stand as remarkable evolutionary success stories in the Galapagos archipelago. Their hydrodynamic bodies and powerful swimming abilities demonstrate natural selection at work in an isolated ecosystem. The reptiles’ distinctive black coloration absorbs vital solar energy, while their specialized salt-expelling glands solve the fundamental problem of marine existence. Their long, compressed tails provide essential propulsion underwater, and their sharp claws anchor them against powerful ocean currents.

Understanding these endemic reptiles (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) illuminates broader principles of adaptation and specialization in island biogeography. Their marine herbivore niche represents a unique evolutionary pathway among modern iguanids. By appreciating these remarkable creatures, we gain insight into both the resilience and vulnerability of specialized species in our rapidly changing global environment.