Rhynchocephalia, a unique order within the class Reptilia, represents a fascinating lineage that has captivated herpetologists and nature enthusiasts alike. Often referred to by its sole extant member, the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), this ancient group offers a glimpse into reptilian evolution, showcasing characteristics that have remained relatively unchanged for millions of years. Unlike most reptiles, tuataras possess a distinctive parietal eye, a third eye located on the top of their heads, which plays a role in regulating their circadian rhythms and reproductive cycles.

Found primarily in the lush ecosystems of New Zealand, tuataras are fascinating for their adaptability to both temperate and subtropical habitats. Their unique physiological traits, such as a slow metabolism and a long lifespan, allow them to thrive in environments where other reptiles might struggle. As nocturnal creatures, they exhibit a range of behaviors that illustrate their role in their native ecosystems, including their diet of insects, small vertebrates, and plant matter.

Historically, rhynchocephalians were more diverse, with numerous species inhabiting various regions across the globe. Today, the tuatara stands as a living testament to the resilience of this ancient lineage, symbolizing the importance of conservation in preserving biodiversity. Facing challenges from habitat loss and climate change, the tuatara’s survival is a critical reminder of the delicate balance within ecosystems.

Join us as we explore the intriguing world of Rhynchocephalia, uncovering the evolutionary history, unique adaptations, and conservation efforts necessary to protect these reptiles for future generations.

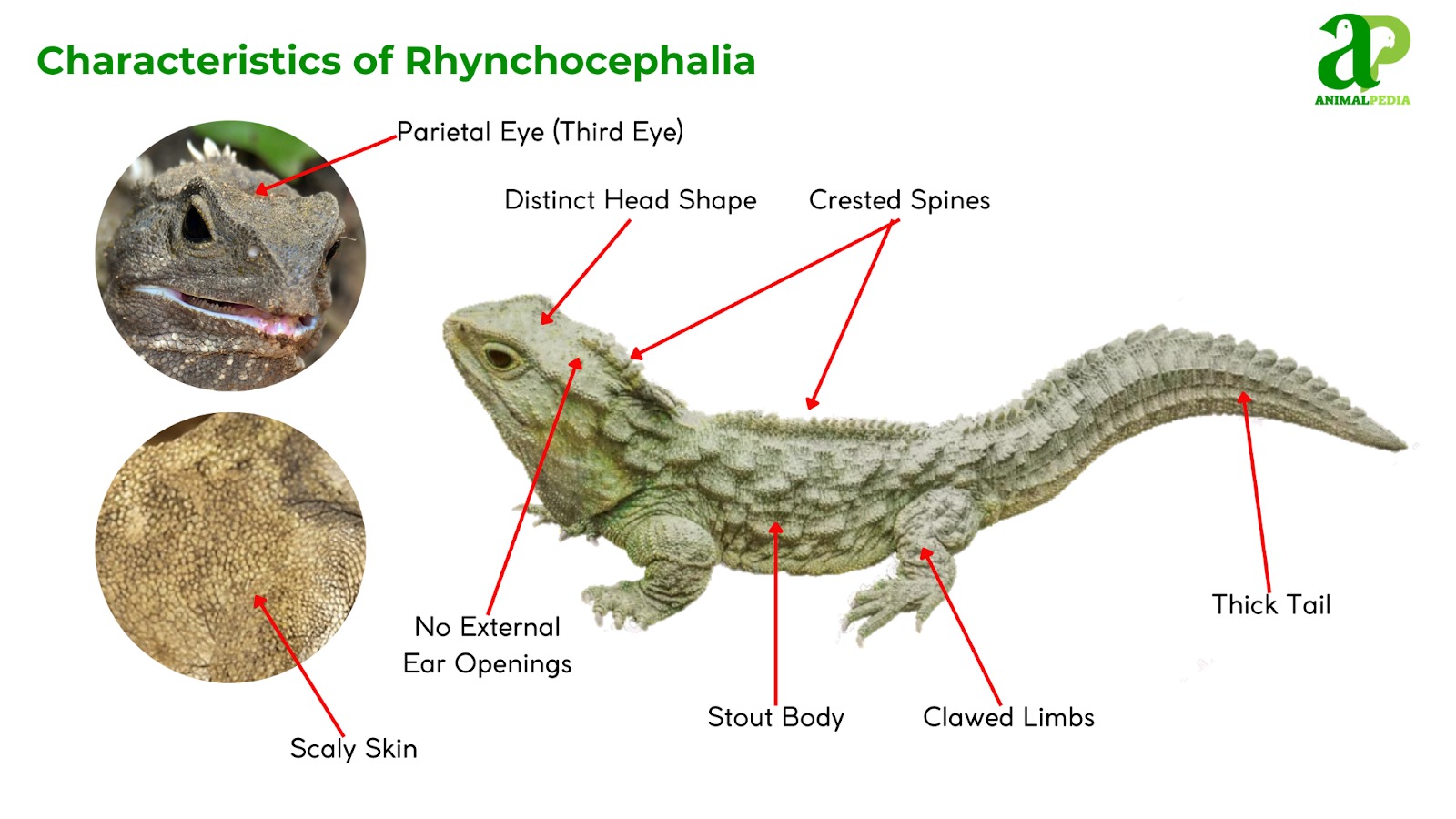

What are the characteristics of Rhynchocephalia?

Rhynchocephalia has outstanding features as follows

- 12 to 31 inches (30 to 80 centimeters) in length and 0.44 to 2.2 pounds (200 and 1,000 grams) in weight.

- Two layers of skins made of alpha and beta keratin.

- Beta-keratin spiky crest.

- Sharp, acrodont, non-replacing teeth with shearing function.

- Highly adaptable, night-vision eyes with a unique third eye.

Let’s explore these adaptations in greater detail, beginning with their size and physical features.

Size

Rhynchocephalia exhibits a range in size across different species and sexes. Generally, they are considered relatively small to moderately sized reptiles compared to their kin.

Adult Rhynchocephalia can range from approximately 12 to 31 inches (30 to 80 centimeters) in total length (snout to tail). This body length can vary significantly depending on the species, with some individuals reaching lengths closer to the upper end of this spectrum.

The weight of Rhynchocephalia also demonstrates considerable variation, influenced by factors such as age, sex, and overall health. Adult Rhynchocephalia typically weigh between 0.44 to 2.2 pounds (200 and 1,000 grams), with more prominent individuals usually males.

The heavyweight champion of the Rhynchocephalia family is the Sphenodon punctatus, also known as the tuatara. These impressive reptiles can reach sizes of up to 24 inches (60 centimeters) in length and weigh around 2.2 pounds (1 kilogram). This species is endemic to two islands in New Zealand: North Island and Stephens Island.

Skin

Rhynchocephalia’s skin consists of two main layers: the epidermis, which contains hardened scales made of alpha and beta keratin, and the dermis, which is rich in collagen, providing elasticity and protection. Unlike many reptiles, they lack large skin glands that produce mucus or toxins, making their skin uniquely adapted to their environment.

A distinctive feature is their gastralia system—a set of belly bones that support movement and provide extra protection. Combined with keratinized scales, this system minimizes water loss and shields against physical damage. While the exact chemical composition of tuatara skin is not well studied, it likely contains high concentrations of oleic acid (45.62%) and palmitic acid (39.87%), similar to other reptiles, aiding in flexibility and hydration retention.

Their skin also plays a role in thermoregulation, with darker pigmentation absorbing heat. During reproduction, slight skin color changes signal mating readiness, and specialized male scales provide protection during encounters. Unlike snakes and lizards, tuatara shed their skin in small patches, a gradual process that reduces damage, highlighting another adaptation crucial to their survival.

Spiky Crest

The spiky crest of Rhynchocephalia is a defining feature made of beta-keratin scales. Running from head to tail, it is more pronounced in males and lacks a bony structure, making it purely integumentary.

This crest plays key roles in social interactions. Males raise their crests to assert dominance in territorial disputes and attract mates during breeding season, with larger crests signaling better health and genetics. It also serves as a defense mechanism—creating an illusion of greater size to deter predators.

Additionally, the crest aids thermoregulation by increasing surface area for heat exchange, helping tuataras maintain optimal body temperature. It even provides slight mechanical protection in physical encounters.

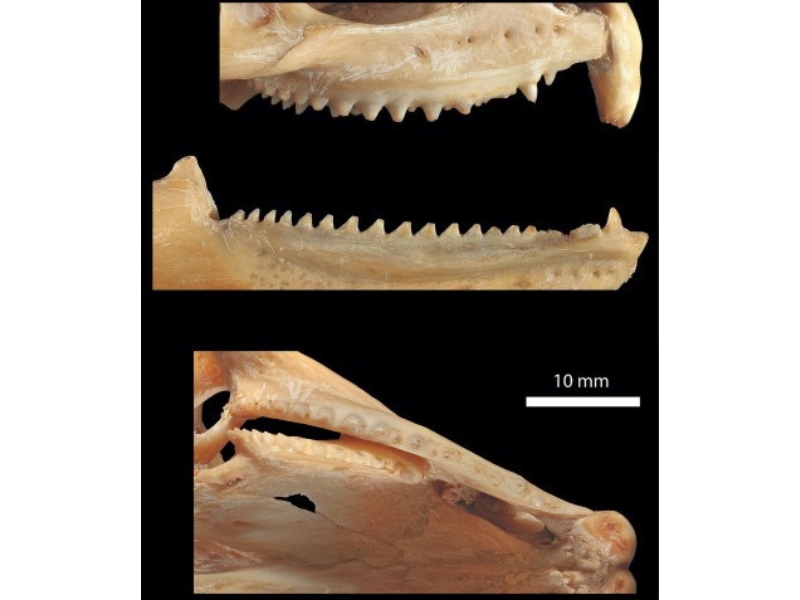

Teeth

Rhynchocephalia’s teeth include small cylindrical, broad, and slender types, with anterior teeth being acrodont—fused directly to the jawbone without roots. Some prehistoric species had both pleurodont (shallow-rooted) and acrodont teeth, indicating an evolutionary transition.

Tuatara teeth have an enamel hardness of 4.00 GPa and an elastic modulus of 73.17 GPa, lower than mammals. Their thin, non-prismatic enamel minimizes wear. Unlike snakes and lizards, tuatara do not replace lost teeth; instead, their jawbone develops sharp edges for cutting.

They use a propalinal (forward-backward) chewing motion, shearing prey like insects and small vertebrates. Teeth also aid in defense and competition, inflicting deep wounds. Evolutionarily, Rhynchocephalia developed diverse dentition, from sharp carnivorous teeth to plate-like structures for crushing, enabling them to exploit various ecological niches and even compete with early mammals.

Eyes

The main eyes of Rhynchocephalia resemble those of modern reptiles, featuring corneas, lenses, and retinas. With an accommodative ability of up to 8 diopters, they can adjust focus flexibly. Uniquely, each eye can move independently, enhancing their field of vision.

A defining trait is their parietal eye, a third eye atop the head. Though it cannot form images, it detects light intensity and regulates circadian rhythms, a feature found only in Rhynchocephalia and some lizards. Their retinas contain rod and cone cells, providing excellent low-light vision, essential for nocturnal hunting. Their cornea’s optical power of 101 diopters ensures sharp visual acuity, aiding in prey detection.

Beyond sight, their visual system plays key roles in survival. The parietal eye acts as a natural light meter, regulating melatonin and daily activity cycles. Independent eye movement allows for a broad visual field, crucial for spotting predators. Additionally, their eyes aid in social interactions by detecting subtle light changes, helping them respond to environmental cues. These adaptations have supported the tuatara’s survival for millions of years.

Which is the exception of Rhynchocephalia?

There is no exception in the Rhynchocephalia order since the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) is the only living member. The tuatara’s unique traits and status as a “living fossil” make it an extraordinary representative of Rhynchocephalia.

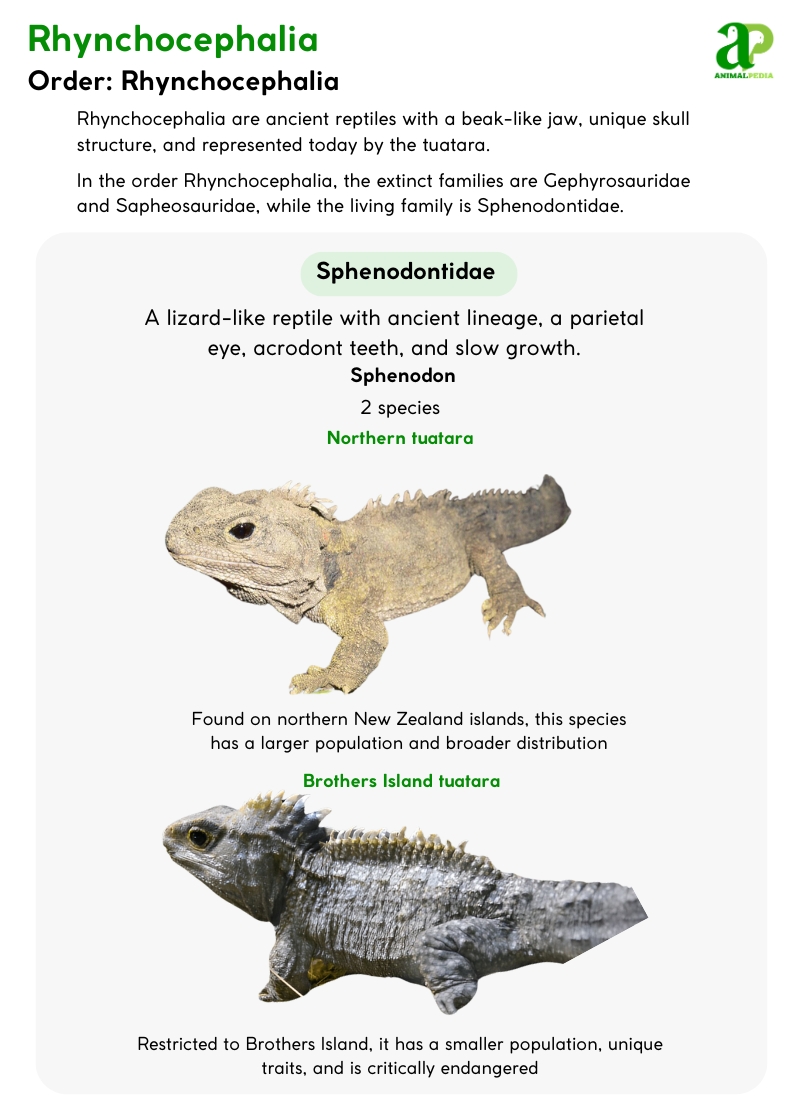

How is Rhynchocephalia classified?

The classification of families within the order Rhynchocephalia is based on evolutionary relationships and morphological characteristics. This order primarily consists of lizard-like reptiles, with the only extant representative being the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus). The division into families reflects both historical classifications and modern phylogenetic analyses.

There are three families in the Rhynchocephalia order, but only one is still alive nowadays.

- Sphenodontidae: Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus). Tuataras are the only living representatives of this ancient lineage, characterized by their diapsid skulls, which possess two temporal fenestrae (openings) behind the eyes, a feature shared with many reptiles but distinct in its arrangement.

- Clevosauridae: An extinct family known from fossils, recognizable by unique teeth and skull structures that set them apart from modern tuataras.

- Gephyrosauridae: Another extinct family with some members showing links to modern lizards (squamates), hinting at a complex evolutionary past.

Here’s a simplified diagram of Rhynchocephalia’s classification:

Rhynchocephalia

└── Sphenodontia (Suborder)

├── Sphenodontidae (Family)

│ └── Sphenodon (Genus, includes the tuatara): 2 species

├── Gephyrosauridae (Family, extinct)

└── Sapheosauridae (Family, extinct)

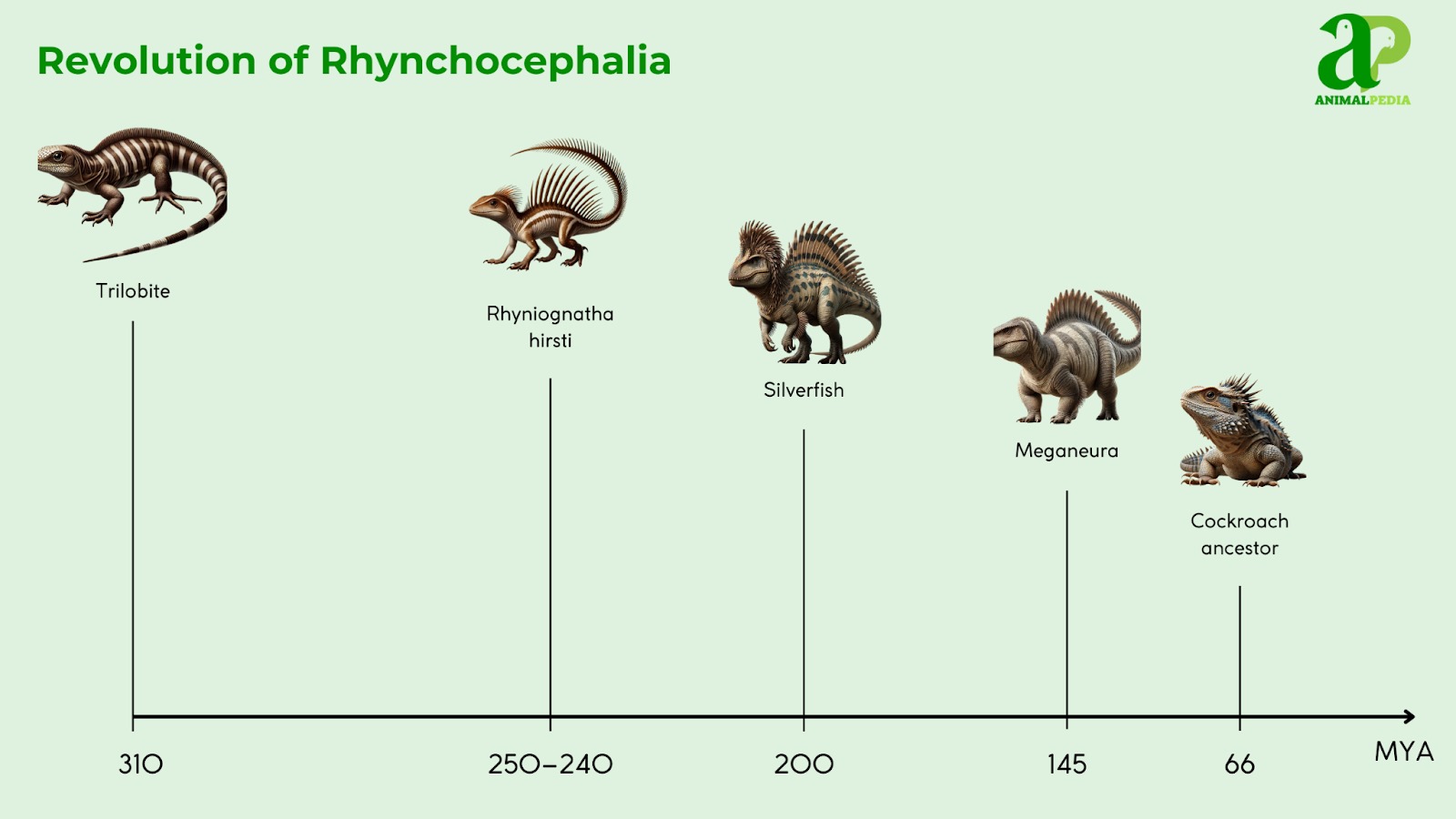

What did Rhynchocephalia evolve from?

Rhynchocephalia evolved from early Lepidosauromorpha, a group of reptiles that also gave rise to squamates (lizards and snakes). Their closest ancestors were primitive diapsid reptiles that emerged in the Late Permian to Early Triassic, around 250 million years ago.

- 310–250 Million Years Ago (Late Carboniferous – Permian Periods)

Around 310 million years ago, the ancestors of Rhynchocephalia and Squamata (lizards & snakes) first appeared. By 260–250 million years ago, small reptiles like Paliguana and Sophineta showed traits common to both groups, marking the early stages of their evolutionary path.

- 250–240 Million Years Ago (Early Triassic Period)

Rhynchocephalia diverged from squamates and began evolving independently. Fossils of Gephyrosaurus and Diphydontosaurus from this period reveal early rhynchocephalians with simple teeth and lizard-like bodies, establishing their distinct lineage.

- 200–145 Million Years Ago (Jurassic Period)

This period marked their peak diversity. Some species, like Eilenodon robustus, evolved herbivorous diets, while others, such as Clevosaurus, developed sharp teeth for carnivory. Aquatic adaptations also emerged in the Pleurosauridae family. By 150 million years ago, rhynchocephalians were widespread, with fossils found in Europe, North & South America, and India.

- 145–66 Million Years Ago (Cretaceous Period)

Rhynchocephalia began to decline due to competition with faster-reproducing squamates and the rise of mammals. By 80–66 million years ago, they were nearly extinct, surviving only in isolated regions.

- 66 Million Years Ago – Present (Cenozoic Era)

Following the K-Pg extinction (~66 MYA), the tuatara remained as the sole survivor. Its ability to adapt to cooler climates, slow metabolism, and long lifespan helped it persist while other rhynchocephalians vanished. Remaining largely unchanged for ~200 million years, the tuatara stands as a true “living fossil.”

Where does Rhynchocephalia live?

The tuatara is endemic to New Zealand. These ancient reptiles are found on approximately 30 offshore islands, primarily in predator-free environments. Natural populations exist on Stephens Island, Little Barrier Island, and Brothers Island, while conservation efforts have led to successful reintroductions in protected reserves such as Zealandia in Wellington.

Tuatara inhabit coastal forests, shrublands, and rocky areas, where they rely on burrows for shelter. In some cases, they even share these burrows with seabirds, benefiting from the warmth and protection of their nests. Their specialized habitat preferences and isolation on predator-free islands have been crucial to their survival, allowing them to persist despite the decline of their ancient relatives.

What are the behaviors of Rhynchocephalia?

The behaviors of Rhynchocephalia highlight their unique evolutionary adaptations for survival as follows.

- Diet: a nocturnal ambush predator with a carnivorous diet, feeding on insects, spiders, small reptiles, and bird eggs. Its unique shearing bite enables precise prey slicing, enhancing hunting efficiency.

- Burrowing: Tuataras create and utilize burrows to regulate body temperature, conserve energy during inactivity, and protect themselves from predators. Burrows also play a role in social interactions, such as establishing territories or attracting mates.

- Sun Basking: As ectothermic reptiles, tuataras bask in sunlight to absorb heat for metabolic functions, digestion, and muscle activity. Basking also facilitates vitamin D synthesis for healthy bone and scale development.

- Courtship Rituals: Male tuataras exhibit complex courtship behaviors, including releasing pheromones, rhythmic head-bobbing, and producing low-frequency vocalizations (“chur calls”) to attract mates and establish dominance.

- Reproduction: Tuataras are oviparous, laying eggs after a unique courtship and mating process. Females breed every 2-5 years, and hatchling sex is determined by nest temperature, a phenomenon known as temperature-dependent sex determination.

Let’s explore diet and feeding behavior, an essential survival strategy for tuataras.

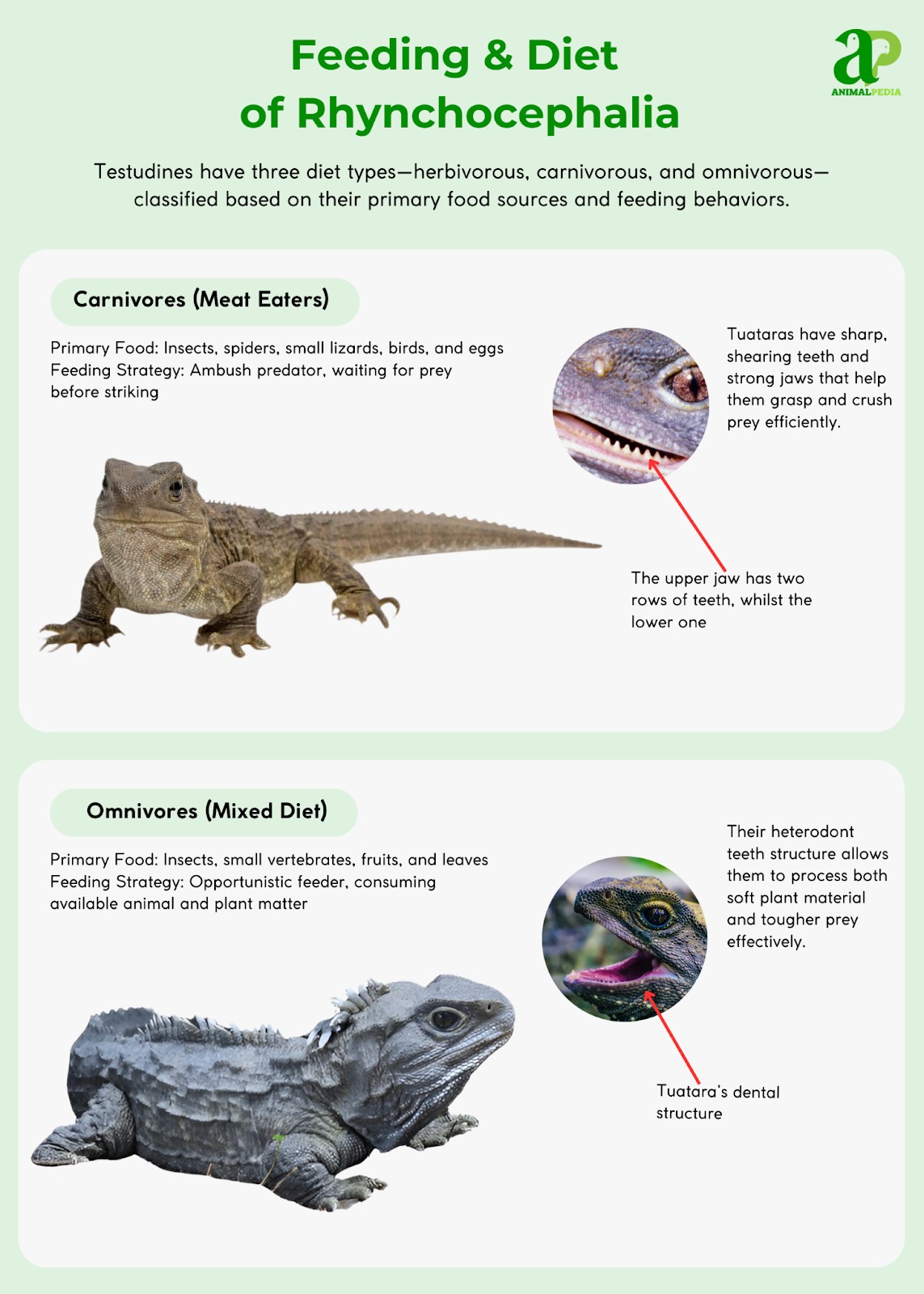

Diet & Feeding Behavior

As a carnivore, its diet includes a variety of prey. Tuatara primarily consume insects such as beetles, crickets, and grasshoppers, along with spiders, which form a significant part of their diet in certain regions. They also feed on small reptiles, occasionally preying on lizards, and opportunistically consume bird eggs and chicks, especially from seabirds.

Though rare, they may also eat amphibians and carrion when available. Interestingly, some extinct rhynchocephalians, like Eilenodon robustus, were herbivorous, possessing broad teeth suited for grinding plant material.

Their “proal bite” involves the lower jaw sliding forward and backward, creating a shearing motion similar to a draw-cut saw. This adaptation allows them to slice prey with precision rather than chewing. Fossil evidence suggests that extinct relatives, such as Clevosaurus, had blade-like teeth similar to those of mammalian carnassials, indicating a strong bite force suited for slicing prey.

Their hunting strategy relies on ambush predation, where they remain still and strike quickly when prey comes within reach. Being nocturnal hunters, tuatara primarily feed at night, using their well-adapted vision to locate prey. They are also known to raid seabird burrows, taking advantage of hidden nests to steal eggs and chicks, showcasing their opportunistic and adaptive feeding behavior.

Burrowing

Burrowing behavior is vital for the survival of tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus and Sphenodon guntheri), the last living members of the Rhynchocephalia order. Their burrows provide a stable microclimate for thermoregulation, allowing them to escape extreme temperatures and maintain their preferred body temperature. These subterranean shelters also protect them from predators, offering a safe retreat.

Tuatara use their strong limbs and sharp claws to dig burrows or repurpose existing cavities in rocks, soil, or vegetation. Burrows are essential during periods of inactivity, such as hibernation in winter or aestivation in summer, helping tuatara conserve energy, avoid desiccation, and minimize water loss.

In addition to providing refuge, burrows play a role in tuatara’s social interactions. They may defend burrow entrances to establish dominance or attract mates. Factors like age, sex, weather, and habitat conditions influence burrowing habits. Juveniles often dig less elaborate burrows, while males may excavate to establish territories or enhance mating opportunities.

Sun Basking

Sun basking is a vital behavior for tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus and Sphenodon guntheri), helping them regulate body temperature and optimize physiological functions. As ectothermic reptiles, basking in sunlight allows tuatara to absorb external heat, boosting their metabolism, aiding digestion, and enhancing muscle function.

Sunlight exposure is also essential for vitamin D synthesis, enabling proper calcium metabolism for strong bones and scales, crucial for movement and protection. Beyond physical benefits, basking helps tuatara balance activity and rest by efficiently regulating their body temperature.

Tuatara strategically select basking spots, such as exposed rocks, logs, or vegetation edges, depending on their thermoregulatory needs. The duration of basking varies based on ambient temperature, metabolic requirements, and activity levels, ranging from brief sessions to longer periods for maintaining optimal body heat.

Courtship Rituals

Courtship in tuatara is a sensory-rich process led by males, who use various behaviors to attract mates. They release pheromones from glands near their vent to signal reproductive readiness and mark territories. Males also perform rhythmic head-bobbing displays, often gaping their mouths to capture the female’s attention and assert dominance.

Vocalizations, known as “chur calls,” add an auditory element to courtship. These low-frequency sounds, emitted during the breeding season, likely aid in communication between males and females, potentially attracting mates or asserting territory.

Males may also circle around females, sometimes incorporating gentle nuzzling, to display interest and establish a connection. By combining visual, chemical, and auditory cues, male tuatara aim to impress females and boost their reproductive success.

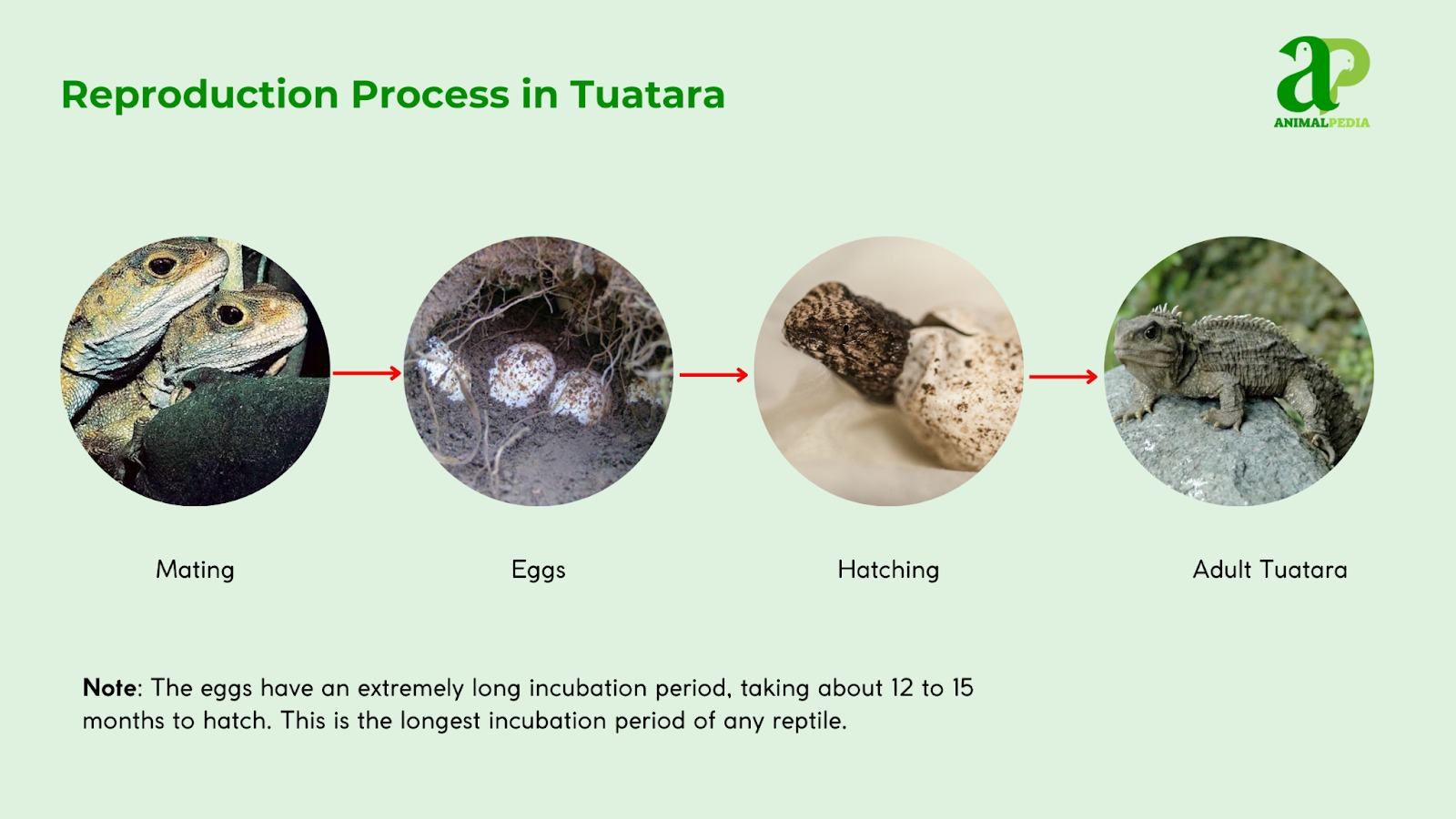

How Do Rhynchocephalia Reproduce?

The tuatara reproduces via oviparity, laying eggs instead of bearing live young. Their reproductive cycle is highly adapted, with females breeding every 2-5 years and males capable of annual mating. Courtship occurs during the southern hemisphere’s summer (January to March), with males performing a distinctive “proud walk,” characterized by an elevated posture, to attract females.

Unlike most reptiles, tuataras lack external reproductive organs, relying on a “cloacal kiss” for sperm transfer. After mating, females lay 4-18 eggs in spring, with clutches averaging 6-7 eggs. The eggs are buried in nests that range from shallow depressions to depths of 50 cm, requiring precise environmental conditions for development.

Parental care is limited, but females exhibit advanced nest-selection behavior to enhance hatchling survival. Nest temperature significantly influences offspring sex: warmer conditions (above 22°C) generally produce males, while cooler conditions yield females.

After emerging, hatchlings are fully independent, capable of hunting and self-defense. While they receive no parental care, juveniles often stay near their hatching site for several months as they establish territorial behavior. These adaptations highlight the tuatara’s unique evolutionary strategy and its survival in a narrow ecological niche.

What is the relationship between Rhynchocephalia and Humans?

The Rhynchocephalia holds immense importance in science, conservation, culture, and education. This ancient reptilian lineage provides valuable insights into evolution, environmental health, and biological research.

- Scientific & Evolutionary Importance

Tuatara are often called “living fossils” because they have remained largely unchanged for over 250 million years. As the closest living relatives to the common ancestor of lizards and snakes, they help scientists understand the evolution of lepidosaurs.

Their parietal eye (a light-sensitive organ) provides insights into circadian rhythms and pineal gland evolution, while their slow metabolism and extreme longevity (100+ years) offer clues about aging and metabolic regulation. Additionally, tuatara thrive in cold environments, unlike most reptiles, making them useful for studying climate adaptation and temperature-dependent biology.

- Conservation & Ecological Importance

Tuatara serve as bioindicators, meaning their health reflects changes in the environment. Their temperature-dependent sex determination is directly affected by climate change, influencing conservation efforts. As predators of insects, small reptiles, and birds, they help regulate prey populations, while their burrow-sharing behavior with seabirds contributes to soil aeration and nutrient cycling.

- Medical & Genetic Research Potential

Their slow metabolism and genetic stability make tuatara a potential model for studying anti-aging mechanisms. Research on their gut microbiome has revealed unique bacterial species that may improve our understanding of digestion and nutrient absorption.

- Cultural & Historical Significance

In Māori mythology, tuatara are considered sacred guardians of knowledge and symbols of longevity and resilience. They are also recognized as national treasures in New Zealand, where strict conservation laws protect their populations.

- Educational & Ecotourism Value

Tuatara attracts global attention, contributing to ecotourism and conservation awareness. They serve as valuable educational tools, helping people learn about evolution, biodiversity, and the importance of protecting endangered species.

Are Rhynchocephalia going endangered?

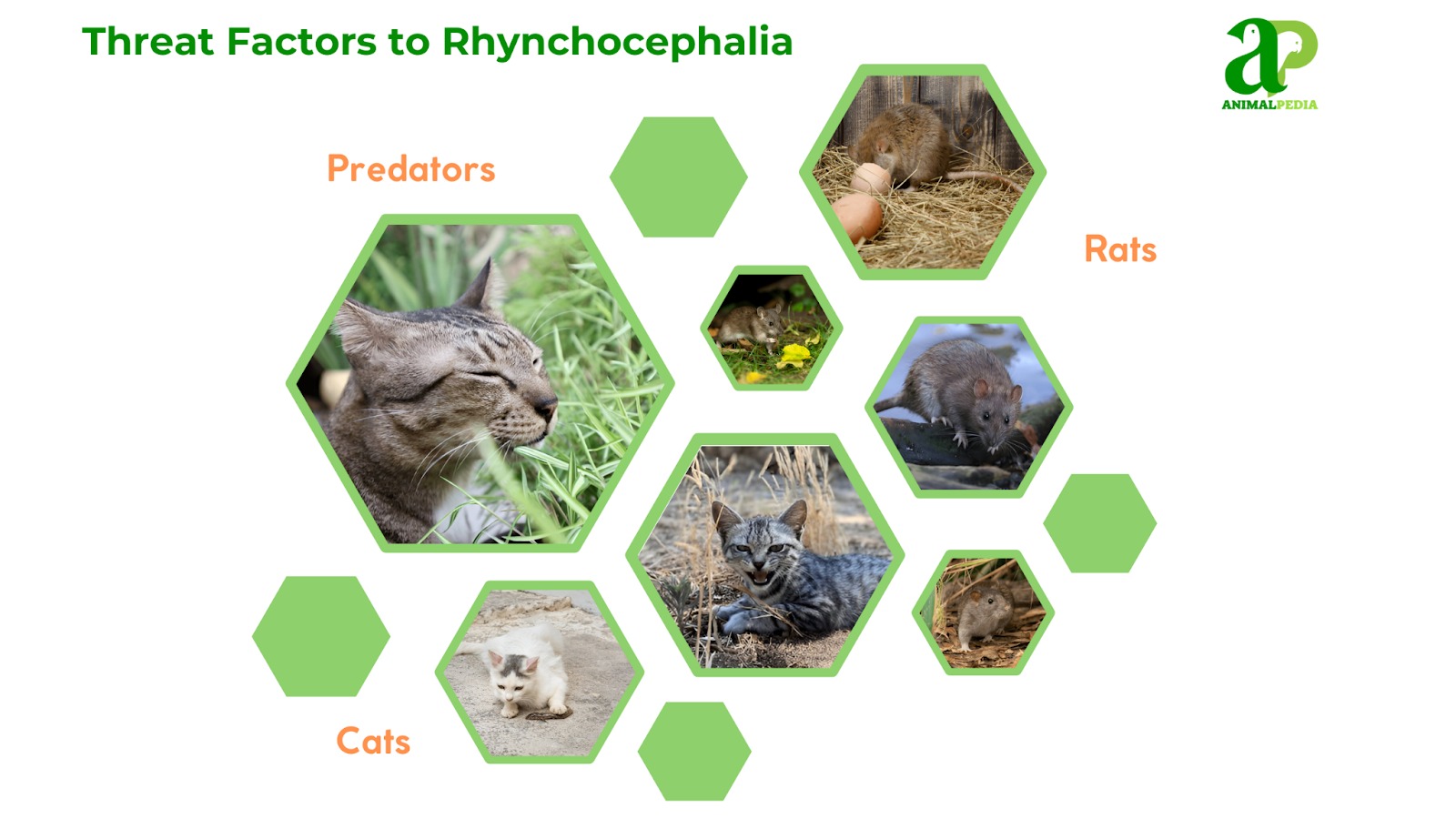

No, Rhynchocephalia, particularly tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus and Sphenodon guntheri) do not face significant predation pressure from native land-dwelling animals, because they have isolated on islands free from mammalian predators for millions of years. As a result, however, introduced predators that humans have introduced to their habitats can threaten Rhynchocephalia populations.

Introduced predators have had a significant impact on Rhynchocephalia, particularly the tuatara, by preying on their eggs, juveniles, and even adults. The following are some specific invasive species that pose a major threat to tuatara populations:

- Rats: Invasive rat species, such as the Pacific rat (Rattus exulans) and Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus), can threaten tuatara eggs, juveniles, and even adult individuals. They are known to prey upon eggs and young tuatara, reducing the survival rates of the population.

- Cats: Feral and domestic cats (Felis catus) are known to prey upon tuatara, particularly young individuals. Cats are agile hunters and can pose a significant threat to tuatara populations, especially in areas where they are abundant.

Rhynchocephalia have evolved in the absence of mammalian predators, and as a result, they do not have a natural fear response to mammalian predators. However, it’s important to note that they may still perceive mammals as potential threats due to their general instincts and responses to unfamiliar stimuli.

While tuatara may not have specific fears of particular species, they may exhibit defensive behaviors or attempt to flee when faced with potential predators. However, their specific responses to different predators have not been extensively studied due to their isolated and protected habitat.

Conservation

Organizations like the Department of Conservation (DOC) play a pivotal role in crafting and implementing protection strategies for tuatara. Establishing wildlife sanctuaries and national parks has provided much-needed safe havens for these vulnerable reptiles. Breeding and population management programs have also been instrumental in bolstering tuatara numbers.

These programs involve breeding tuatara in controlled environments, sometimes utilizing techniques like head-starting (raising young tuatara in captivity until less vulnerable) to increase their chances of survival upon release. A crucial benefit of these programs is preserving genetic diversity within the wild population, ensuring their long-term resilience.

New Zealand has taken commendable steps to protect Rhynchocephalia through a robust legal framework. The Wildlife Conservation Act of 1953 serves as a cornerstone of these efforts, regulating hunting, trade, and the overall well-being of tuatara. Conservation areas and national parks provide crucial protected areas for tuatara populations. Additionally, control programs target invasive species to minimize their predation pressure.

Lifespan of Rhynchocephalia

The average tuatara in the wild can live for 60 to 100 years, with some individuals documented to have surpassed a century. While information on the lifespans of other Rhynchocephalia species is limited due to the scarcity of extant species and ongoing research, it’s likely they also exhibited extended lifespans.

The key to unlocking the secrets of Rhynchocephalia longevity lies in a fascinating interplay between their physiological makeup and the environment. Factors like telomere length (protective caps on chromosomes) and potentially unique metabolic processes might contribute to their extended lifespans.

The quality and availability of their natural habitat also play a crucial role. Suitable habitats that provide access to essential resources like food and water, coupled with a relative absence of significant environmental stressors, can contribute to the health and longevity of Rhynchocephalia populations. Unfortunately, human activities can have a double-edged sword effect on their lifespans.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between Rhynchocephalia and squamata?

Rhynchocephalians, closely related to squamates, are now represented solely by the two species of tuataras in the genus Sphenodon. While resembling lizards in appearance, tuataras possess unique skeletal traits, such as gastralia (abdominal ribs), distinguishing them from squamates.

Are there any close relatives of the Rhynchocephalia order?

The Rhynchocephalia order is considered to be a distinct and unique reptile lineage. Its closest relatives are believed to be the squamates, which include lizards and snakes. However, the exact evolutionary relationships between Rhynchocephalia and squamates are still a subject of scientific investigation and debate. Rhynchocephalia represents a distinct branch of reptiles with its own set of unique characteristics and evolutionary history.

Can you keep a tuatara as a pet?

No, you cannot own a tuatara as a pet. These highly protected species are endemic to New Zealand, and their export is strictly prohibited. Additionally, their specialized care needs make them unsuitable for private ownership.

Can a tuatara regrow its tail?

Tuatara can regenerate parts of their tails, but the process is notably slow. Since this regeneration occurs alongside body growth, it is often referred to as “regengrow,” highlighting the simultaneous nature of regeneration and growth.

Rhynchocephalia, represented today solely by the tuatara, stands as a living testament to reptilian resilience and evolutionary history. This fascinating order, with its ancient lineage dating back over 230 million years, continues to intrigue scientists and nature enthusiasts alike. From its unique anatomical features to its ecological role in New Zealand’s habitats, the tuatara exemplifies survival amidst changing times. Efforts in conservation have become vital to protect this species from modern threats. Exploring the world of Rhynchocephalia offers a glimpse into Earth’s past and underscores the importance of preserving its biodiversity for the future.