Salamanders, amphibians with slender bodies and long tails, boast over 700 species. Notable species include Ambystoma mexicanum (axolotl) and Salamandra salamandra (fire salamander). They thrive globally, from North America’s Appalachian Mountains to Japan’s Honshu Island, preferring damp forests and streams.

The axolotl, famed for limb regeneration, grows to 30 cm, while fire salamanders, with bold black-yellow patterns, reach 20 cm. Their moist skin and vibrant colors, often with spots or stripes, distinguish them. These traits highlight their adaptability and ecological roles.

Salamanders are not apex predators but skilled hunters. They ambush insects, worms, and small invertebrates, using sticky tongues for prey capture. Their diet is specialized, focusing on soft-bodied organisms, with minimal human interaction, though habitat encroachment poses risks.

Reproduction varies; most breed in spring, laying eggs in water or moist soil. Egg clutches range from 10-400, hatching in 2-8 weeks. Larvae metamorphose in months, reaching maturity in 1-3 years. Lifespans average 10-20 years, with some axolotls exceeding 15 years in captivity.

This article explores salamanders’ appearance, habitats, and behaviors, delving into their ecological significance and unique adaptations for survival.

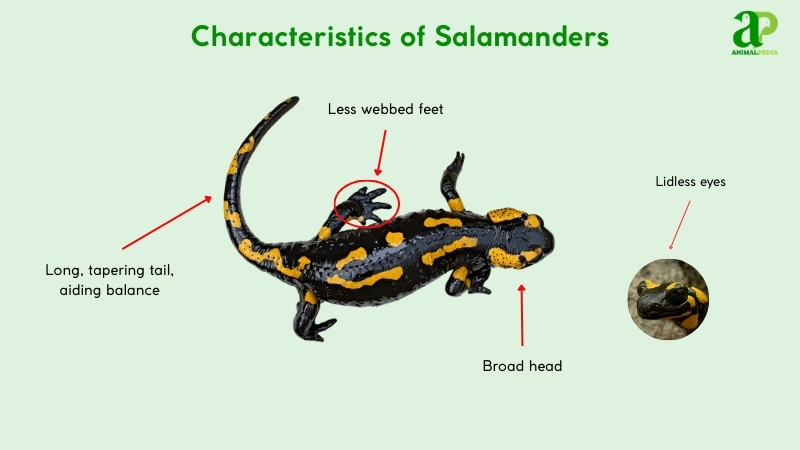

What do the Salamanders look like?

Salamanders have sleek, elongated bodies, measuring 10-30 cm (4-12 inches) long. Their smooth, moist skin lacks scales. Coloration varies widely—axolotls (Ambystoma mexicanum) display pale pink or black with speckles, while fire salamanders (Salamandra salamandra) show bold black with yellow patterns. Their permeable skin feels slick and functions in respiration.

Their anatomy includes a broad head with small, lidless eyes for sharp vision; a sticky tongue for capturing prey; a flexible neck; a cylindrical trunk; four short limbs with 4-5 digits; and a long, tapering tail that often comprises half their length, aiding balance and locomotion.

Terrestrial salamanders have less webbed feet than newts. Their heads appear flatter than frogs, with larger, rounder eyes than lizards. Axolotls uniquely retain external gills as adults, unlike most species that lose them after metamorphosis. The vivid markings on fire salamanders signal toxicity—a trait less evident in plainer species like the red-backed salamander (Plethodon cinereus). These distinctive features—gill structure, warning coloration, and foot morphology—define salamanders within amphibian classification.

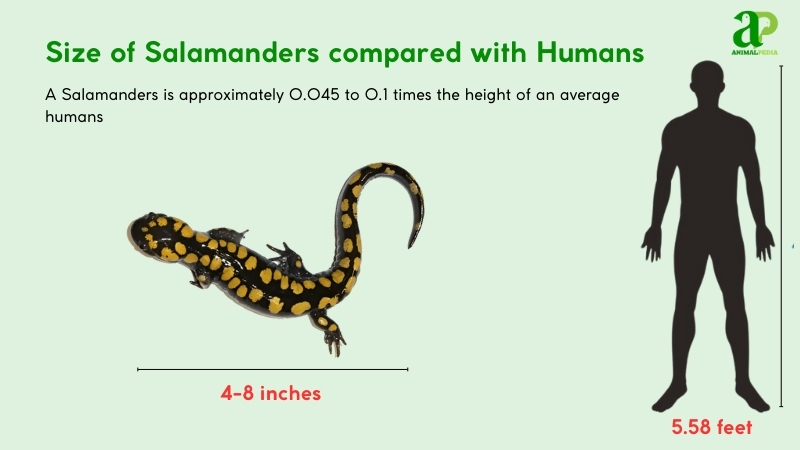

How big do Salamanders get?

Salamanders average 4-8 inches (10-20 cm) in length and weigh 0.02-0.1 lbs (10-50 grams). These amphibians vary widely, with smaller species like the pygmy salamander (Thorius spp.) at 1.18 inches (3 cm) and larger ones reaching greater sizes.

The largest, the Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus), grows to 5.9 feet (1.8 meters) and 110 lbs (50 kg), discovered in China’s Yangtze River basin, per AmphibiaWeb (2020). Adults typically measure 15 cm snout to tail for common species like the fire salamander. Males and females show minimal size differences, with females slightly larger for egg-carrying.

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 5.5–5.9 in (14–15 cm) | 5.9–6.2 in (15-16 cm) |

| Weight | 0.02–0.08 lbs (10–40 g) | 0.08–0.1 lbs (15–50 g) |

What are the unique physical characteristics of the species?

Salamanders possess a remarkable trait: cutaneous respiration. This allows oxygen absorption through their moist, permeable skin—a feature rare among vertebrates. Many species like the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) retain external gills into adulthood, enabling aquatic breathing without lungs.

Research by Vitt and Caldwell (2019) shows how this skin-based respiration ensures survival in damp environments. Blood vessels positioned near the skin surface maximize gas exchange efficiency. The axolotl’s feathery gill structures stand unique among amphibians, maintaining oxygen uptake in stagnant waters. This distinguishes them from lung-dependent species like newts, which shed their gills after metamorphosis.

How do Salamanders sense their environment with its unique features?

Salamanders sense their environment through cutaneous respiration, absorbing oxygen through their moist skin as they navigate damp forests and streams. This specialized respiration supports their energy requirements for hunting and predator avoidance in low-oxygen habitats.

Their acute vision detects minimal movement, enabling successful prey capture even in low light conditions. Chemical detection occurs through specialized sensory receptors on their skin that interpret environmental cues, guiding navigation and reproductive behaviors. Mechanoreceptors in their limbs sense ground vibrations, providing early warning of approaching threats. Olfactory perception via highly developed nasal passages helps track food sources, particularly enhancing their foraging efficiency in turbid aquatic environments.

Anatomy

Salamanders possess unique anatomical adaptations that reflect their dual life in water and on land. Their physiology serves survival in moist environments, from forest floors to freshwater habitats. Each organ system contributes to their hunting, breathing, and predator evasion with remarkable efficiency.

- Respiratory System: Moist skin and gills (in some species) enable cutaneous respiration, supplemented by simple pulmonary structures for oxygen absorption in damp microhabitats.

- Circulatory System: A three-chambered heart pumps blood efficiently, supporting low-metabolic lifestyles with oxygen transport to integumentary surfaces and locomotor muscles.

- Digestive System: Short alimentary canal processes arthropods and annelids quickly, with a projectile tongue aiding prey capture across diverse ecological niches.

- Excretory System: Mesonephric kidneys filter nitrogenous waste, producing dilute urine to maintain optimal hydration in wet sylvan or aquatic environments.

- Nervous System: Compact cephalic ganglia with acute sensory afferents drive rapid responses to threats and food sources, enhancing survival in dynamic ecosystems.

These integrated systems enable salamanders to thrive as stealthy, adaptable urodele amphibians. Their anatomy reflects both evolutionary heritage and specialized adaptations for life in the fluctuating conditions of mesic terrestrial and lentic aquatic habitats.

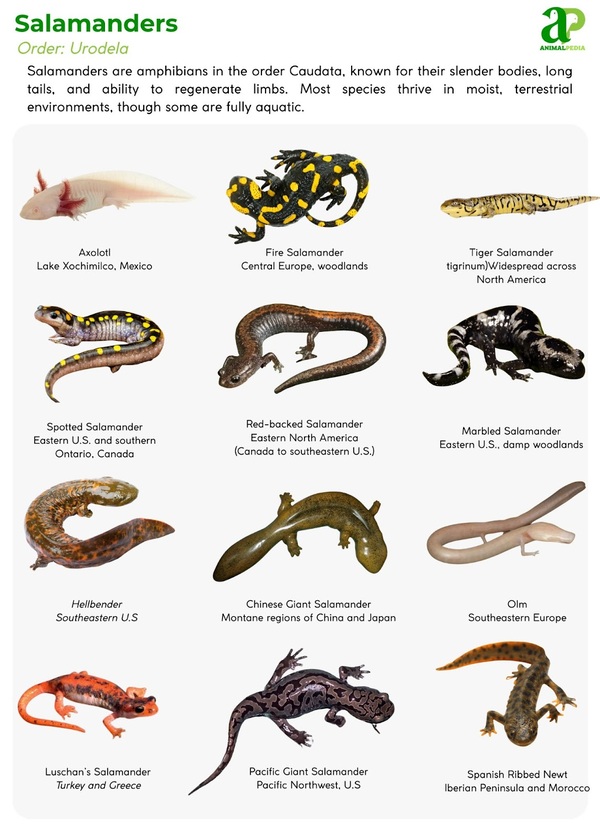

How many types of Salamanders?

Over 700 salamander species exist within the order Caudata. Classification follows the Linnaean system, established by Carl Linnaeus, grouping species by shared traits like limb structure and reproductive habits.

The taxonomic hierarchy branches as: Order Caudata → Families (e.g., Salamandridae, Ambystomatidae) → Genera → Species.

Order Caudata

├── Family Salamandridae

│ └── Genus Salamandra (e.g., S. salamandra)

└── Family Ambystomatidae

└── Genus Ambystoma (e.g., A. mexicanum)

Special cases include paedomorphic species like axolotls, retaining juvenile traits, challenging traditional classifications.

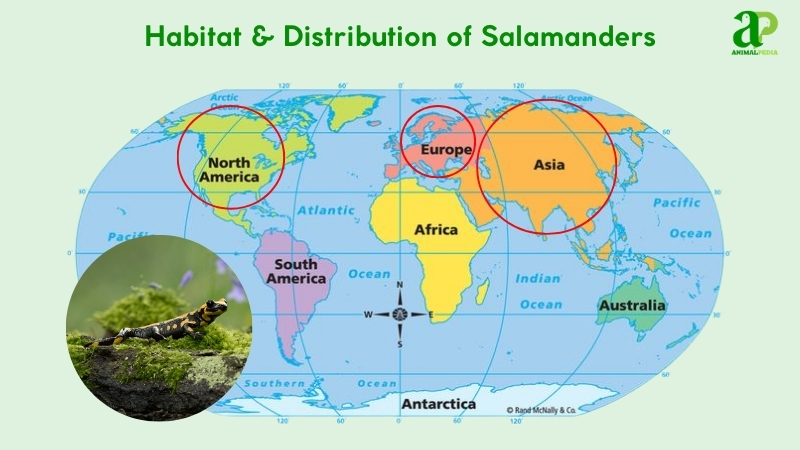

Where do Salamanders live?

Salamanders inhabit North America, Europe, and Asia, with thriving populations in the Appalachian Mountains, Honshu Island (Japan), and Mediterranean forests. They prefer damp habitats including woodland floors, mountain streams, and limestone caves.

These amphibians require moisture-rich environments for their permeable skin and reproduction needs. The stable, cool conditions of these regions support their low-metabolic lifestyle and provide essential breeding grounds.

Research by Vitt and Caldwell (2019) shows these urodele amphibians have occupied these territories for millions of years. Their limited dispersal patterns reflect evolutionary adaptation to specific microhabitats that meet their ecological requirements.

How do seasonal changes affect their behavior?

Salamanders show distinct seasonal behavior shifts tied directly to temperature and moisture. These adaptations optimize survival in changing environments.

During the wet season (March–August), salamanders increase foraging and mating. The abundant moisture and prey availability fuel their activity and reproduction cycles.

In the cool-dry season (September–February), they reduce movement significantly. Many species enter torpor or hibernation in colder regions, with some burrowing underground to avoid harsh conditions.

These temporal patterns are crucial for energy conservation, population sustainability, and breeding success. Salamanders time their activity with environmental cues like precipitation, photoperiod, and temperature gradients to maximize resource use while avoiding environmental stressors such as drought or freezing.

Microhabitat selection also changes seasonally, with individuals seeking thermal refugia during extreme conditions and selecting optimal breeding sites when moisture levels permit reproduction.

What is the behavior of Salamanders?

Salamanders display a range of behavioral adaptations shaped by their reliance on moist environments. These behaviors are crucial for avoiding desiccation, securing food, reproducing, and interacting with their surroundings.

- Feeding Habits: They ambush insects and worms, using sticky tongues to capture prey. Diet focuses on soft-bodied invertebrates.

- Bite & Venomous: Non-venomous, their bites are weak and defensive. They pose no threat to humans.

- Daily Routines and Movements: Nocturnal, they hide under logs by day, foraging at night. Movements span 1–2 meters nightly.

- Locomotion: They crawl with short limbs, using lateral undulation. Tail aids balance on uneven terrain.

- Social Structures: Mostly solitary, they gather only during mating. Interactions are minimal outside breeding.

- Communication: Chemical cues and body postures signal mating readiness. Vocalizations are rare.

These behavior patterns reflect salamanders’ evolutionary adaptations to their ecological niches. To understand their survival, let’s explore feeding habits in detail.

What do Salamanders eat?

Salamanders are carnivorous, favoring insects, worms, and small invertebrates. Their preferred prey includes beetles and slugs, easily caught with sticky tongues. They do not attack humans, as their diet targets small organisms.

- Diet by Age

Diet varies by age; larvae consume tiny aquatic crustaceans suited to their smaller size and aquatic habitat, and adults feed on larger invertebrates, such as beetles, slugs, and earthworms. Hunting behavior remains consistent across ages, relying on ambush and sticky tongues to catch prey.

- Diet by Gender

No significant dietary differences exist between males and females. Both sexes use identical ambush tactics and consume similar invertebrate prey with flexible jaws allowing both to swallow prey whole, though large prey may be regurgitated.

- Diet by Seasons

Seasonal changes affect prey availability. Wet seasons provide abundant insects, increasing feeding activity and diversity of prey. During dry periods, salamanders eat fewer and smaller invertebrates due to reduced availability. Seasonal feeding adjustments help conserve energy and reduce exposure to dry conditions.

How do Salamanders hunt their prey?

Salamanders hunt with stealth and precision. These amphibians employ varied techniques to capture prey. They wait motionless until prey approaches, then strike with lightning speed.

Specialized adaptations aid their hunting success. Many species possess projectile tongues covered with adhesive secretions that snatch prey in milliseconds. Others rely on rapid lunges to seize passing invertebrates. Their chemosensory abilities allow them to detect prey through smell and taste receptors.

Salamanders display environment-specific hunting strategies. Aquatic species use suction feeding to capture small fish and crustaceans. Terrestrial salamanders ambush insects and arthropods on forest floors. Arboreal species employ their prehensile tails for stability while hunting among branches.

Their locomotor agility enables effective predation across diverse habitats. Most salamanders target invertebrates including worms, insects, and small crustaceans. Larger species may consume small vertebrates. This trophic flexibility allows them to thrive in various ecosystems.

Salamanders function as mesopredators in food webs, controlling invertebrate populations while serving as prey for larger animals. Their hunting behavior represents an evolutionary balance between energy expenditure and nutritional gain.

Are Salamanders Venomous?

Most salamanders lack venom glands, but certain species like the rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa) produce potent defensive neurotoxins. When threatened, these amphibians secrete tetrodotoxin through specialized skin glands—the same compound found in pufferfish. This powerful toxin blocks nerve transmission and can be lethal to predators.

Their aposematic coloration—bright orange underbellies and dark backs—serves as a natural warning signal to potential threats. This vivid pattern effectively communicates toxicity through a biological phenomenon called warning coloration. The salamander’s bright appearance telegraphs danger to would-be predators, creating an effective defense mechanism without physical confrontation.

When are Salamanders most active during the day?

Salamanders show peak activity during the early morning and late afternoon hours. These crepuscular amphibians emerge to forage, mate, and explore during these cooler periods. In morning hours, they actively hunt for invertebrate prey and small organisms across their habitat.

As midday temperatures rise, salamanders retreat to microhabitats – cool, damp refugia beneath rocks, logs, or leaf litter. This behavioral thermoregulation helps them avoid desiccation, as their permeable skin requires consistent moisture.

When temperatures moderate in the late afternoon, salamanders resume their activities. This bimodal activity pattern directly correlates with their physiological need for humid conditions and moderate temperatures. Their ectothermic metabolism functions optimally within specific thermal ranges, typically between 50-70°F (10-21°C).

For field observation of salamander species, targeting these crepuscular periods yields the highest encounter rates. Their temporal niche exploitation represents an evolutionary adaptation to balance predator avoidance, resource acquisition, and physiological constraints.

How do Salamanders move on land and water?

Salamanders move with distinct techniques across terrestrial and aquatic environments. On land, they progress through lateral undulation—a side-to-side body motion—while their limbs provide stability and forward thrust. Their nimble movements let them navigate forest floors, rocky terrain, and vegetation efficiently.

In water, salamanders transform into expert swimmers. Their streamlined bodies and powerful tails generate propulsive waves for movement. Many species possess webbed feet that function like paddles, enhancing their swimming capability. Aquatic salamanders use axial locomotion, where body and tail undulations create thrust while limbs primarily steer.

Some salamanders, like the newts and mudpuppies, demonstrate amphibious locomotion—smoothly transitioning between terrestrial and aquatic movement patterns. Fully aquatic species like the axolotl retain specialized features such as external gills and fin-like tails, optimizing their underwater mobility.

The biomechanics of salamander movement fascinates evolutionary biologists, as these amphibians represent important models for studying the vertebrate transition from water to land. Their locomotion adaptations reflect millions of years of evolutionary refinement across diverse habitats.

Do Salamanders live alone or in groups?

Salamanders vary widely in their social behaviors. Some species live alone, while others gather in groups. The red-backed salamander typically lives a solitary life in damp forest habitats, carving out individual territories and only meeting others during mating season.

By contrast, spotted salamanders exhibit more social tendencies, forming small groups called congresses during breeding periods. These gatherings serve essential reproductive functions for population maintenance.

The social spectrum of salamanders ranges from territorial loners to communal breeders. Their diverse social structures reflect specific ecological adaptations and survival strategies. Amphibian biologists note that habitat conditions, predation pressure, and food availability strongly influence whether a salamander species evolves solitary or group-living behaviors.

How do Salamanders communicate with each other?

Salamanders communicate through three main channels: chemical signals, visual cues, and tactile vibrations. Their primary method involves pheromones—specialized chemical compounds released to transmit information to conspecifics. These chemical messengers serve dual purposes: attracting potential mates during breeding periods and establishing territorial boundaries to ward off rivals.

Visual communication complements chemical signaling in many salamander species. During courtship, males perform species-specific displays that may include distinctive body postures, color intensification, and rhythmic movements. These visual signals help females identify suitable mates of the same species and assess their fitness as potential reproductive partners.

The vibrational communication system represents a less-studied but crucial aspect of salamander interaction. By tail-slapping, body-drumming, or producing substrate vibrations, salamanders create tactile signals that travel through soil or water. These mechanical communications prove especially valuable in dark or turbid environments where visual and even chemical cues might be limited, allowing for multi-modal signaling across various ecological conditions.

How do Salamanders reproduce?

Salamanders reproduce through oviparity (egg-laying) or ovoviviparity (live birth). Breeding season begins in spring, typically March to May. Males deposit spermatophores on the substrate; females collect these with their cloacas. Courtship rituals include nudging behaviors and tail-waving displays, signaling reproductive readiness in moist environments.

Female salamanders lay between 10-400 eggs, each weighing 0.1-0.5 grams, in water or damp soil. They guard their clutches beneath logs or rocks; some species wrap eggs in leaves for protection. Males depart after mating, while females often remain to protect the developing eggs. Environmental stressors like drought or predation can disrupt the egg-laying process.

Eggs hatch within 2-8 weeks. Larvae, primarily aquatic, undergo metamorphosis in 2-6 months, feeding on small invertebrates. Juvenile salamanders reach sexual maturity in 1-3 years.

The life cycle of most salamanders spans 10-20 years. Axolotls represent a unique case, exhibiting neoteny – the retention of larval characteristics throughout life, including external gills and aquatic habitat preference.

How long do Salamanders live?

Salamanders typically live 10-20 years in their natural habitats. Their life cycle progresses from egg to sexual maturity within 1-3 years. Some species, including the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum), display neoteny—retaining juvenile characteristics throughout adulthood.

The average lifespan for common species like the fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) ranges from 12-15 years. Research by Vitt and Caldwell (2019) indicates no significant longevity differences between males and females across salamander taxa. Amphibian lifespans vary based on environmental factors, predation risks, and species-specific metabolism rates.

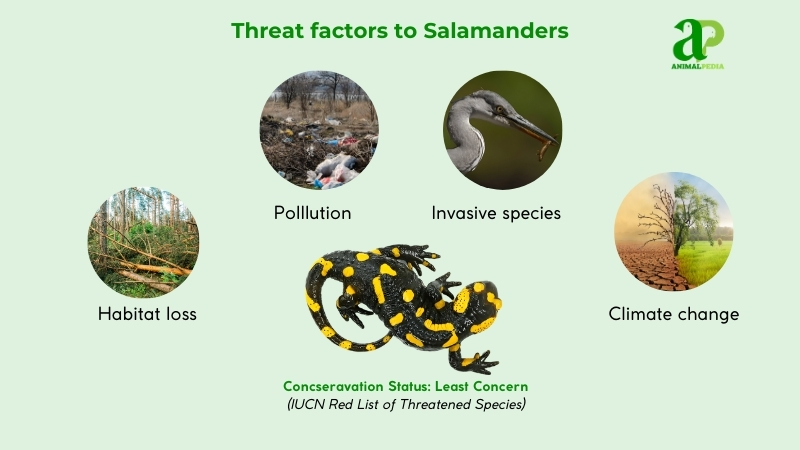

What are the threats or predators that Salamanders face today?

Salamanders face severe threats across their habitats today. These amphibians serve as sensitive bioindicators because their permeable skin absorbs environmental changes directly.

Natural Predators

Salamanders’ primary natural enemies include:

- Wading birds (herons, egrets)

- Reptiles (water snakes, garter snakes)

- Mammals (shrews, raccoons, skunks)

Human-Caused Threats

- Habitat destruction: Deforestation and development have eliminated breeding pools and forest floor habitats, reducing populations by 40% in affected regions.

- Chemical pollution: Pesticides, fertilizers, and industrial runoff penetrate salamanders’ skin, causing 25% mortality rates in contaminated watersheds.

- Climate shifts: Rising temperatures dry crucial microhabitats, reducing egg survival and cutting reproductive success by 20% in warming regions.

- Exotic species: Introduced predatory fish and competing amphibians have decreased salamander abundance by 15% through resource competition and direct predation.

Recent research by Blaustein (2018) confirms these pressures have shrunk salamander ranges by 30% globally since 2000. Their decline signals broader ecosystem deterioration affecting woodland and aquatic habitats worldwide.

Are Salamanders endangered?

Some salamander species face endangered status, while others remain abundant. The IUCN classifies the European fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) as “Least Concern,” but the California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense) is listed as “Vulnerable” due to habitat destruction.

Population trends vary significantly across species. While global salamander numbers reach millions, certain species face critical decline. The axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) now numbers fewer than 1,000 in wild habitats, primarily due to water pollution and urbanization. Fire salamanders maintain relatively stable populations of 100,000-500,000 throughout European forests, according to Blaustein’s 2018 research.

Major conservation threats include urban development, environmental contamination, and amphibian pathogens. The deadly chytrid fungus has caused devastating regional declines, with North American salamander populations decreasing by 30% in recent decades. These declines highlight the urgent need for habitat protection and disease management strategies to prevent further species loss.

What conservation efforts are underway?

Habitat protection and disease prevention drive modern salamander conservation. Since 2016, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has restored critical wetlands and old-growth forests, focusing on endangered species like the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander. Their work established 25 breeding sites by 2020. The Foundation for the Conservation of Salamanders provides annual grants for essential field research.

The Lacey Act amendment (2016) restricts importing 201 salamander species to prevent the deadly Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans fungus. This legislation blocks interstate commerce of listed amphibians without proper permits, creating a protective barrier for native populations.

Captive breeding programs flourish at conservation centers like the Atlanta Amphibian Foundation. Their frosted flatwoods salamander project successfully raised 200 juveniles by 2019, enhancing wild population recovery. The axolotl breeding program expanded 30% between 2015-2020, supporting future reintroduction efforts.

Key conservation entities include the USFWS, FCSal, and USGS Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative. A conservation triumph: the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander‘s breeding habitats increased from just two sites in 1975 to 25 by 2013, primarily through Ellicott Slough National Wildlife Refuge protection measures.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do Salamanders Make Good Pets?

Yes, salamanders can make great pets if you enjoy observing their unique behavior and caring for their specific needs. They offer a fascinating glimpse into the world of amphibians and can be rewarding companions.

Can Salamanders Change Color Like Chameleons?

Yes, salamanders can change color like chameleons. Their ability to adjust hues based on environment and mood allows for camouflage and communication. It’s an impressive feature that keeps them safe and helps them thrive in diverse habitats.

Are All Salamanders Poisonous or Venomous?

No, not all salamanders are poisonous or venomous. Some species have toxins that can be harmful if ingested, while others lack toxicity altogether. Conducting research on different types before handling them is crucial.

Do Salamanders Have Any Unique Defense Mechanisms?

Yes, salamanders have a fascinating defense mechanism. When threatened, they can use their tails to distract predators, allowing them to escape. This unique ability showcases their impressive survival instincts and agility in the wild.

What Is the Lifespan of a Salamander in the Wild?

In the wild, salamanders typically live around 10 to 20 years. Factors like species, environment, and predators influence their lifespan. These fascinating creatures can face diverse challenges but adapt to their surroundings with resilience and grace.

Conclusion

Salamanders stand as remarkable amphibians with striking morphology, habitat versatility, and compelling behaviors. Their camouflage capabilities and nimble locomotion serve them well across terrestrial and aquatic environments. These creatures demonstrate exceptional predation strategies and adaptive mechanisms that ensure their survival against environmental pressures. Caudata species have evolved remarkable regenerative abilities and toxic skin secretions that distinguish them in the amphibian class. Their ecological significance extends to being bioindicators of environmental health in many ecosystems. The next salamander you encounter represents millions of years of evolutionary refinement—a living testament to nature’s ingenuity and resilience.