Squamata represents the largest and most diverse order of living reptiles, comprising all lizards and snakes. With over 11,000 described species, squamates have successfully colonized nearly every terrestrial and marine habitat on Earth, except for the polar regions.

These reptiles range in size from the tiny 0.63 in (16 mm) Brookesia nana chameleon to the massive reticulated python reaching lengths of 21.3 ft (6.5 meters). Squamates are characterized by several distinctive features, including scaleless skin that is periodically shed, a highly mobile skull with a movable quadrate bone, and a specialized chemosensory organ (Jacobson’s organ).

The order is divided into three major suborders: Lacertilia (lizards), Serpentes (snakes), and Amphisbaenia (worm lizards). While most squamates possess four limbs, various lineages have independently evolved limbless body forms, demonstrating evolutionary plasticity in body plan modification.

Squamates display an extraordinary range of behaviors and adaptations that enhance their survival. Many species exhibit camouflage abilities, from the color-changing capabilities of chameleons to the cryptic patterns of vipers. Some, like the flying dragons (Draco species), have developed unique gliding mechanisms, while others show complex social behaviors including parental care and territorial displays. Venom production, particularly advanced in snakes, represents one of their most significant evolutionary innovations, ranging from simple toxic saliva to highly sophisticated venom delivery systems.

Today, squamates exhibit extraordinary diversity in form, behavior, and ecology. They play crucial roles in ecosystems as both predators and prey, contributing to the regulation of pest populations and serving as important indicators of environmental health. Many species display complex social behaviors, advanced hunting strategies, and sophisticated methods of defense against predators.

In this comprehensive article, we’ll explore the fascinating world of Squamata, examining their diverse characteristics, evolutionary innovations, and ecological significance. From their unique anatomical features to their varied reproductive strategies and behaviors, we’ll investigate what makes these reptiles one of the most successful and adaptable groups of vertebrates on Earth.

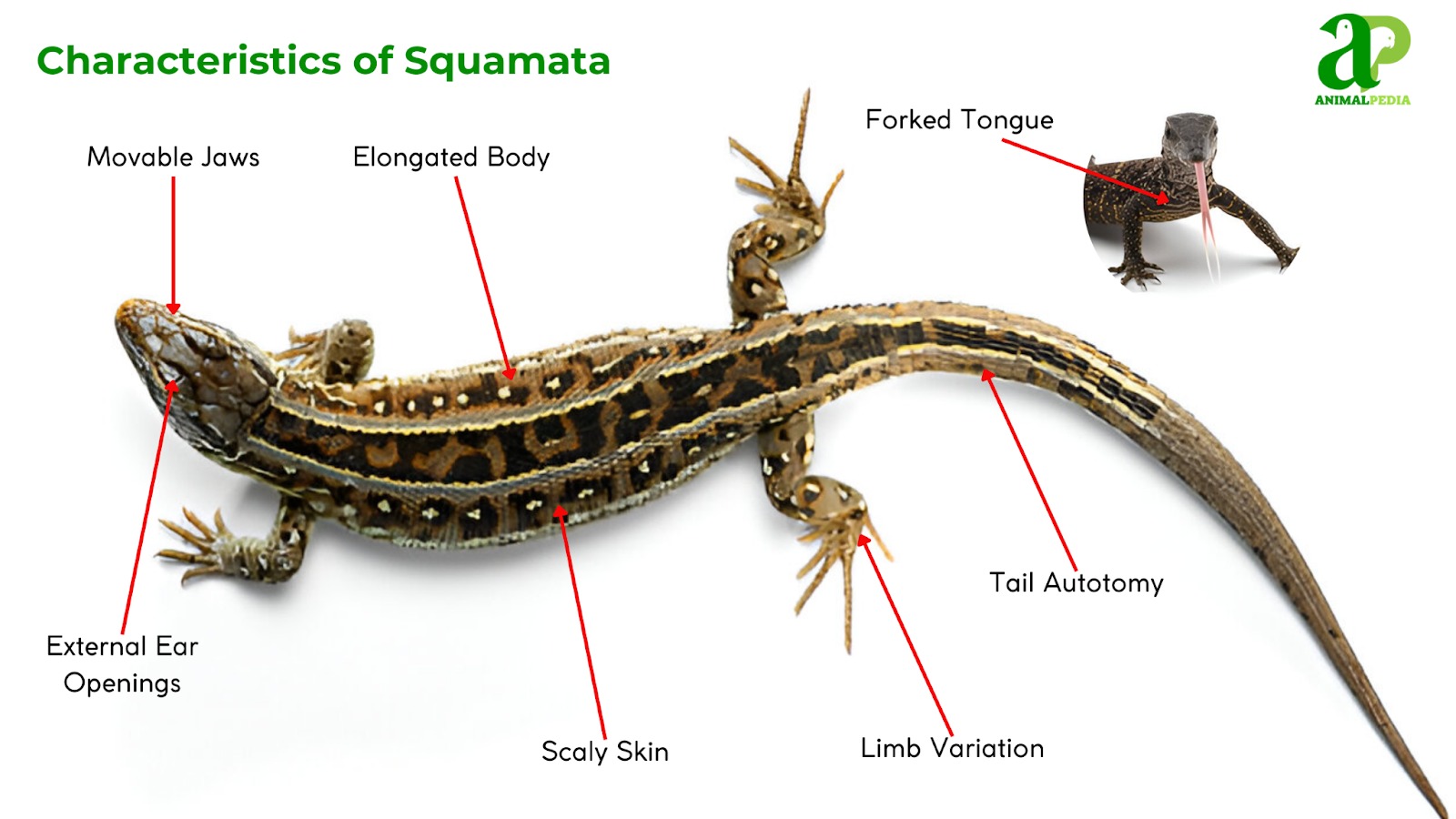

What are Squamata characteristics?

Squamata has 4 features as follows

- The size range is approximately 0.33 ft to 10+ ft.

- Squamate skin, rich in β-keratin, provides protection, water resistance, flexibility, and thermoregulation.

- Skulls are highly mobile, aiding in prey capture, defense, and ecological adaptations.

- Tongues aid in chemoreception, prey capture, and feeding, adapting to diverse ecological needs.

Size

The order Squamata includes an incredibly diverse range of species, from tiny geckos to massive constrictor types of snakes. This diversity allows them to occupy various ecological niches, leading to significant differences in body size.

Most lizards range between 4 to 24 inches (10 cm to 60 cm), though some, like monitor lizards, can grow beyond 6.5 ft (2 m). Snakes vary widely, with common species like garter snakes and rat snakes measuring 1.6 to 5 ft (50 cm to 1.5 m), while large constrictors such as boas and pythons often exceed 10 ft (3 m).

- Smallest Squamate

The nano-chameleon (Brookesia nana) holds the record as the smallest reptile, measuring only 22 mm (0.87 inches) from head to tail. Similarly, dwarf geckos (Sphaerodactylus ariasae) have a body length of just 16 mm (0.63 inches).

- Largest Squamate

Among the largest squamates, the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus) is the heaviest snake, reaching 250 kg (550 lbs) and growing up to 9 m (29.5 ft). The reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) holds the title for the longest snake, with individuals exceeding 10 m (33 ft). The Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) is the largest lizard, reaching 3 m (10 ft) in length and weighing around 70 kg (150 lbs).

Scaly Skin

Squamate skin has three main layers: the stratum corneum, composed of β-keratin for rigidity and water resistance; the stratum granulosum, which contains lipids that minimize water loss; and the stratum basale, responsible for generating new cells.

They rely on β-keratin, which provides superior abrasion resistance and mechanical strength, particularly useful in arid environments. Their scale structure varies based on ecological needs—overlapping scales in snakes and skinks enhance flexibility, granular scales in geckos improve grip, and keeled scales in vipers and some lizards aid in camouflage.

The keratinized skin helps prevent dehydration, crucial for species living in dry environments. The lipid layer in the stratum granulosum reduces water loss, while armor-like scales in some species (e.g., Helodermatidae) offer additional protection. Scale pigmentation influences thermoregulation, with darker species absorbing heat efficiently.

Skull

Squamates (lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians) possess one of the most specialized forms of cranial kinesis (skull mobility) among vertebrates. Cranial kinesis varies across squamates, with most species possessing kinetic skulls, meaning their skull bones can move at specialized joints. In contrast, akinetic skulls, like those in crocodiles, turtles, and mammals, lack such mobility. Squamate skulls exhibit different forms of kinesis depending on their ecological needs.

This mobility enables efficient prey capture, particularly in species that swallow large food items by expanding their jaws. The specialized pterygoid walk mechanism allows gradual ingestion without chewing, while jaw flexibility enhances bite strength, grip, and venom delivery in predatory species.

Skull adaptations also play a role in defense and survival, aiding in threat displays, such as hood expansion or blood-squirting mechanisms, to deter predators. In burrowing species, modifications allow for efficient soil penetration, reducing resistance while digging. Additionally, cranial kinesis supports stealth feeding strategies, where subtle movements help manipulate prey with minimal disturbance.

Tongues

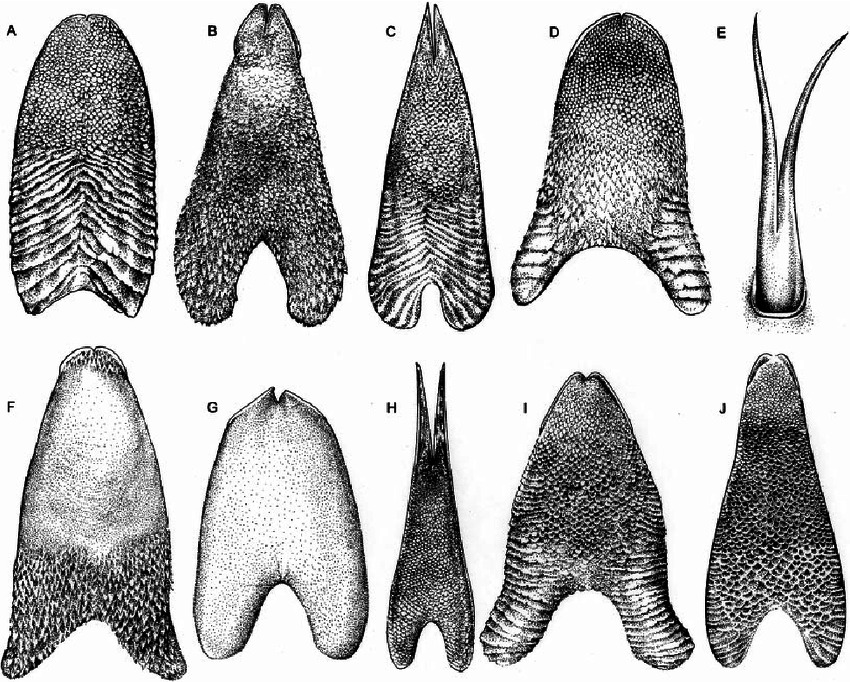

According to the study of El-Mansi & et (2020), the tongue of P. sibilans is divided into three main parts: the apex, body, and root. Morphometric analysis revealed that it is relatively short (0.68 ± 0.01 in) compared to the lower jaw length (2.57 ± 0.14 in), with varying thickness across its regions—0.04 ± 0.005 in at the apex, 0.06 ± 0.015 in at the body, and 0.08 ± 0.02 in at the root.

The tongue epithelium consists of four layers: the stratum basale, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and stratum corneum. The forked tongue tips are positioned in the cranial part of the mandible, near a pair of structures called sublingual plicae. These plicae are slightly inclined toward the midline but gradually diverge as they extend posteriorly along the floor of the mouth. These anatomical adaptations play a crucial role in sensory perception and feeding efficiency.

Variation in tongue form in squamate lizards. (A)Xantusia (Xantusiidae). (B)Abronia (Anguidae). (C)Podarcis(Lacertidae). (D)Coleonyx (Gekkonidae). (E)Varanus (Varanidae). (F)Gonocephalus (Agamidae). (G)Crotophytus (Iguanidae).(H)Cnemidophorus (Teiidae). (I)Cordylus (Cordylidae). (J)Dasia (Scincidae). (From Schwenk, ’95; Drawing by M. J. Spring.

The tongues of squamates serve key functions in chemoreception, prey capture, and feeding adaptations. Many use forked tongues to collect airborne particles, transferring them to the Jacobson’s organ for precise scent tracking. Some lizards rely on tongue grasping for prey capture, while chameleons use ballistic tongues for rapid insect hunting. Certain species employ lingual luring, mimicking prey movement to attract victims.

In aquatic environments, some squamates lack functional tongues and instead rely on jaw suction to capture prey. These diverse adaptations highlight the crucial role of the tongue in squamate survival and ecological success.

According to a comprehensive study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution (2020), Squamata has demonstrated evolutionary success, with the highest species diversification rate among all reptile groups.

“This group’s extraordinary adaptability and diverse survival strategies have made them key players in nearly every terrestrial ecosystem.” notes Dr. Robert Henderson, curator emeritus of herpetology at the Milwaukee Public Museum. Research shows that Squamates occupy crucial ecological roles, from pest control to seed dispersal, making them essential contributors to ecosystem stability and biodiversity maintenance.

Which is the exception of Squamata?

In terms of the reproduction method, the Blind lizards (Amphisbaenidae) and three gecko families—Gekkonidae, Phyllodactylidae, and Sphaerodactylidae—produce eggs with hard, calcified shells while most Squamata lay eggs with parchment-like shells.

Here is the difference between calcified shells and parchment-like shells:

|

Feature |

Calcified Shells (Hard-Shelled Eggs) |

Parchment-Like Shells (Soft-Shelled Eggs) |

| Structure & Composition | Thick, rigid shell with high calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) content | Thin, flexible, leathery shell with low calcium content |

| Texture | Hard, brittle, and crystalline | Soft, pliable, and leathery |

| Water Permeability | Low permeability, reducing water loss | High permeability, allowing water absorption from the environment |

| Protection | Provides strong mechanical protection against predators and environmental damage | More susceptible to desiccation and physical damage |

| Gas Exchange | Micropores facilitate oxygen diffusion while minimizing dehydration | More direct water and gas exchange with surroundings |

| Nesting Environment | Adapted for open nests in dry habitats or exposed areas | Laid in moist environments like soil or leaf litter |

| Adaptations | Prevents excessive water loss, suited for drier environments | Reduces egg breakage in confined spaces, suited for burrowing species |

| Examples | Crocodiles (Crocodylia) – Hard-shelled eggs buried in nests

Some Turtles (Cheloniidae) – Some aquatic turtles lay calcified eggs |

Snakes (Serpentes) – Most lay soft eggs, but some are viviparous

Lizards (Lacertilia) – Many, including geckos, lay parchment-like eggs Soft-Shelled Turtles (Trionychidae) – Lay pliable eggs in humid environments |

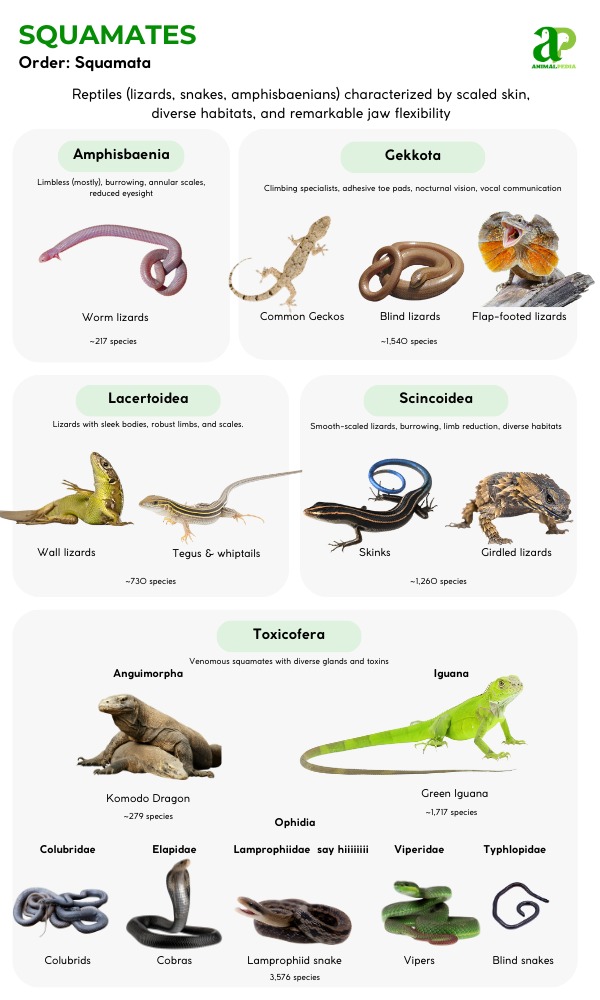

How is Squamata classified?

The classification of Squamata is based on the recent phylogenetic providing insights into the evolutionary relationships among squamates, leading to revisions in classification at the suborder, family and subfamily levels

Testudines are divided into 6 suborders and 63 families, encompassing a diverse range of species adapted to different ecological niches.

Suborder Amphisbaenia: Commonly known as worm lizards, this disorder characterized by. Amphisbaenians have elongated, cylindrical bodies and are adapted for a burrowing lifestyle. Some species have reduced or absent limbs, enhancing their ability to move through soil and leaf litter. They are primarily fossorial, spending most of their lives underground.

Two outstanding families in Amphisbaenia are:

- Amphisbaenidae – Includes common worm lizards, found mainly in South America.

- Rhineuridae – Includes the North American worm lizard, the only amphisbaenian native to the United States (Florida).

Suborder Lacertilia (or Sauria): This suborder primarily includes lizards. Typically features four limbs, a long tail, and a movable eyelid. Lizards exhibit diverse adaptations for various habitats, from arboreal to terrestrial environments. They often have varied diets, including insects, plants, and small vertebrates. Many lizards lay eggs (oviparous), while some species give birth to live young (viviparous).

Four popular families in Lacertilia order includes:

- Iguanidae – Includes iguanas and marine iguanas, primarily herbivorous and found in the Americas.

- Chamaeleonidae – Includes chameleons, famous for independent eye movement, projectile tongues, and color-changing abilities.

- Gekkonidae – Encompasses common house geckos and tokay geckos, featuring nocturnal habits and adhesive toe pads for climbing.

- Varanidae – Includes monitor lizards, such as the Komodo dragon, characterized by large size, carnivorous diet, and high intelligence.

Suborder Serpentes: Snakes lack external limbs, a significant evolutionary adaptation. They have elongated, flexible bodies with a unique method of locomotion, allowing them to navigate through various environments. Snakes possess specialized jaws that enable them to swallow prey whole, often consuming animals larger than themselves. Many snakes have developed heat-sensing pits to detect warm-blooded prey.

Here are four well-known families of Serpentes suborders:

- Viperidae – Includes rattlesnakes and vipers, possessing hinged fangs (solenoglyphous) and potent venom.

- Elapidae – Comprises cobras, mambas, and coral snakes, distinguished by fixed front fangs and neurotoxic venom.

- Pythonidae – Features pythons, large constrictors that lay eggs rather than give birth to live young.

- Hydrophiidae – Comprises sea snakes, which are fully aquatic and highly venomous.

Here is a simplified diagram for understanding the relationship between the above suborders and families of Squamata:

Amphisbaenia

│ └──Family: Amphisbaenidae (Tropical worm lizards) (~200 species)

│ └──Family: Bipedidae (Bipes worm lizards) (~3 species)

│ └──Family: Blanidae (Mediterranean worm lizards) (~5 species)

│ └──Family: Cadeidae (Cuban worm lizards) (~2 species)

│ └──Family: Rhineuridae (North American worm lizards) (1 species)

│ └──Family: Trogonophidae (Palearctic worm lizards) (~6 species)

Gekkota

│ └──Family: Carphodactylidae (Southern padless geckos) (~30 species)

│ └──Family: Dibamidae (Blind lizards) (~20 species)

│ └──Family: Diplodactylidae (Australasian geckos) (~130 species)

│ └──Family: Eublepharidae (Eyelid geckos) (~30 species)

│ └──Family: Gekkonidae (Common geckos) (~950 species)

│ └──Family: Phyllodactylidae (Leaf finger geckos) (~140 species)

│ └──Family: Pygopodidae (Flap-footed lizards) (~40 species)

│ └──Family: Sphaerodactylidae (Round finger geckos) (~200 species)

Lacertoidea

│ └──Family: Alopoglossidae (Alopoglossid lizards) (~20 species)

│ └──Family: Gymnophthalmidae (Spectacled lizards) (~250 species)

│ └──Family: Lacertidae (Wall lizards) (~320 species)

│ └──Family: Teiidae (Tegus and whiptails) (~140 species)

Scincoidea

│ └──Family: Cordylidae (Girdled lizards) (~60 species)

│ └──Family: Gerrhosauridae (Plated lizards) (~30 species)

│ └──Family: Scincidae (Skinks) (~1500 species)

│ └──Family: Xantusiidae (Night lizards) (~30 species)

Toxicofera

├──Anguimorpha

│ └──Family: Anguidae (Glass lizards, alligator lizards, and slowworms) (~130 species)

│ └──Family: Anniellidae (American legless lizards) (~6 species)

│ └──Family: Diploglossidae (Galliwasps and legless lizards) (~50 species)

│ └──Family: Helodermatidae (Beaded lizards) (~2 species)

│ └──Family: Lanthanotidae (Earless monitor) (1 species, Lanthanotus borneensis)

│ └──Family: Shinisauridae (Chinese crocodile lizard) (1 species, Shinisaurus crocodilurus)

│ └──Family: Varanidae (Monitor lizards) (~79 species)

│ └──Family: Xenosauridae (Knob-scaled lizards) (~10 species)

├──Iguana

│ └──Family: Agamidae (Agamas) (~400 species)

│ └──Family: Chamaeleonidae (Chameleons) (~200 species)

│ └──Family: Corytophanidae (Casquehead lizards) (~9 species)

│ └──Family: Crotaphytidae (Collared and leopard lizards) (~12 species)

│ └──Family: Dactyloidae (Anoles) (~400 species)

│ └──Family: Hoplocercidae (Wood lizards or clubtails) (~17 species)

│ └──Family: Iguanidae (Iguanas) (~40 species)

│ └──Family: Leiocephalidae (Curly-tailed lizards) (~29 species)

│ └──Family: Leiosauridae (Leiosaurid lizards) (~34 species)

│ └──Family: Liolaemidae (Tree iguanas and snow swifts) (~299 species)

│ └──Family: Opluridae (Malagasy iguanas) (~8 species)

│ └──Family: Phrynosomatidae (Earless, spiny, tree, side-blotched and horned lizards) (~148 species)

│ └──Family: Polychrotidae (Bush anoles) (1 species)

│ └──Family: Tropiduridae (Neotropical ground lizards) (~120 species)

├──Ophidia

├── └──Alethinophidia

│ └──Family: Acrochordidae (File snakes) (~3 species)

│ └──Family: Aniliidae (Coral pipe snakes) (1 species)

│ └──Family: Anomochilidae (Dwarf pipe snakes) (~3 species)

│ └──Family: Boidae (Boas) (~60 species)

│ └──Family: Bolyeriidae (Round Island boas) (1 species)

│ └──Family: Colubridae (Colubrids) (~1800 species)

│ └──Family: Cylindrophiidae (Asian pipe snakes) (~10 species)

│ └──Family: Elapidae (Cobras, coral snakes, mambas, kraits, sea snakes, sea kraits, Australian elapids) (~390 species)

│ └──Family: Homalopsidae (Indo-Australian water snakes, mud snakes, buck adams) (~50 species)

│ └──Family: Lamprophiidae (Lamprophiid snakes) (~300 species)

│ └──Family: Loxocemidae (Mexican burrowing snakes) (1 species)

│ └──Family: Pareidae (Pareid snakes) (~30 species)

│ └──Family: Pythonidae (Pythons) (~40 species)

│ └──Family: Tropidophiidae (Dwarf boas) (~30 species)

│ └──Family: Uropeltidae (Shield-tailed snakes, short-tailed snakes) (~50 species)

│ └──Family: Viperidae (Vipers, pitvipers, rattlesnakes) (~360 species)

│ └──Family: Xenodermidae (Odd-scaled snakes and relatives) (~18 species)

│ └──Family: Xenopeltidae (Sunbeam snakes) (~2 species)

├── └──Scolecophidia

│ └──Family: Anomalepidae (Dawn blind snakes) (~18 species)

│ └──Family: Gerrhopilidae (Indo-Malayan blindsnakes) (~18 species)

│ └──Family: Leptotyphlopidae (Slender blind snakes) (~140 species)

│ └──Family: Typhlopidae (Blind snakes) (~250 species)

│ └──Family: Xenotyphlopidae (Malagasy blind snakes) (1 species)

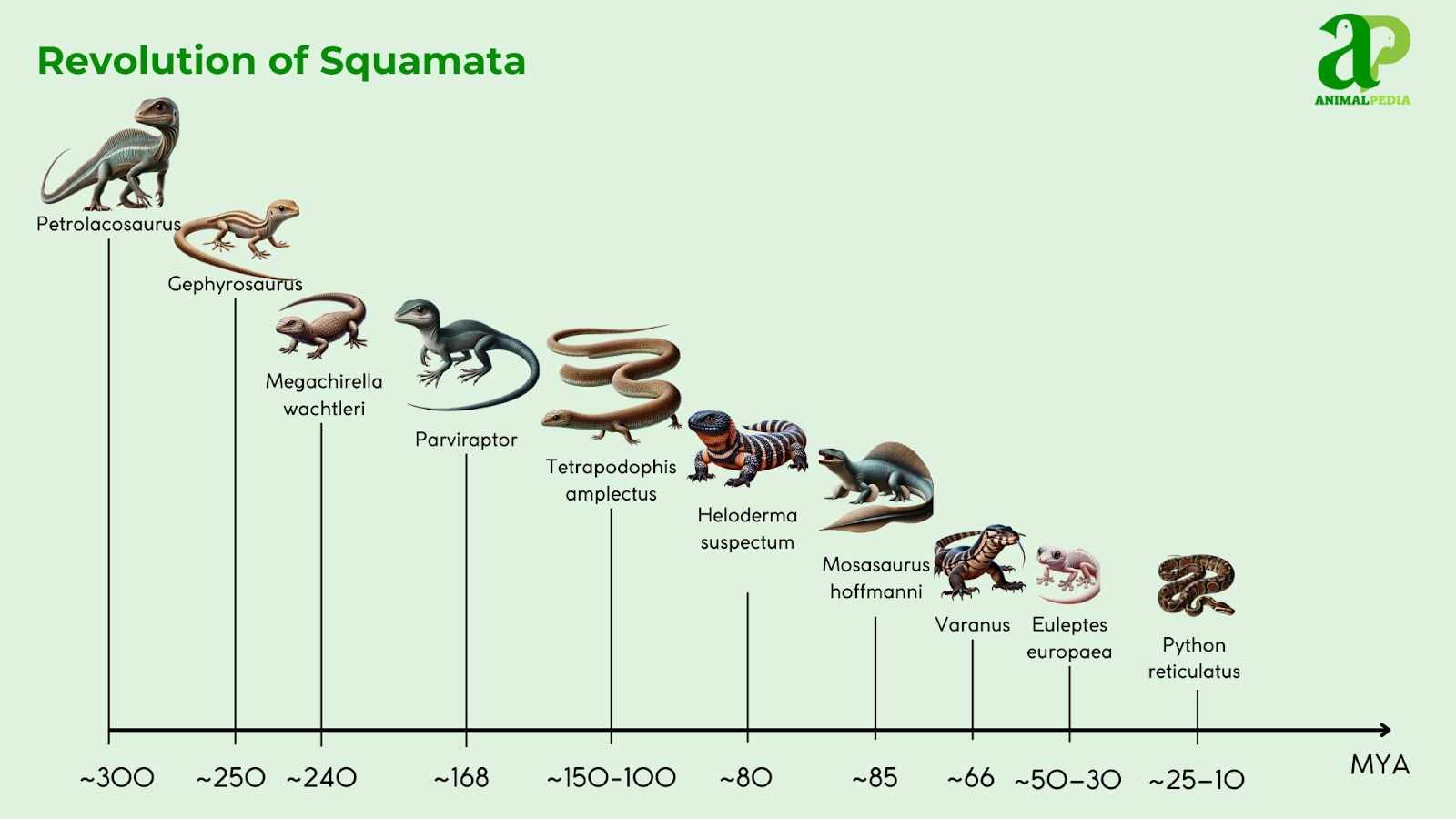

What did Squamata evolve from?

Squamata evolved from early lepidosaurian reptiles, a group that shares a common ancestor with Rhynchocephalia (represented today by the tuatara, Sphenodon). The evolutionary history of Squamates spans over 300 million years, marked by significant transitions and adaptations that shaped modern lizards and snakes.

- ~300 million years ago, Late Carboniferous – Early Permian: Origin of Diapsids

Diapsids, the ancestors of Squamata, were reptiles distinguished by two temporal fenestrae—skull openings that enhanced jaw muscle strength. These early diapsids evolved into several lineages, one of which gave rise to Lepidosauria, the group that later included Squamata.

- ~250 million years ago, Early Triassic: Divergence of Lepidosauria

During the Early Triassic, Lepidosauria diverged into two primary groups: Rhynchocephalia (which includes modern tuataras) and Squamata (encompassing lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians). Early lepidosaurians were small, slender-bodied creatures that likely resembled modern skinks.

- ~240 million years ago, Middle Triassic: Oldest Known Squamate Fossil

The discovery of Megachirella wachtleri, the earliest known squamate fossil, provides compelling evidence that Squamata had already evolved by this period. Phylogenetic analysis places Megachirella as a crucial transitional form, bridging early lepidosaurs and modern squamates.

- ~168 million years ago, Middle Jurassic: Early Squamate Radiation

Fossil records from the Middle Jurassic indicate an early diversification of lizards, with forms resembling modern geckos and skinks. Squamates began to occupy various ecological niches, adapting to different environmental conditions.

- ~100-150 million years ago, Late Jurassic – Early Cretaceous: Origin of Snakes

Early snake fossils, such as Najash rionegrina (95 million years ago) and Tetrapodophis (120 million years ago), still retained small hind limbs, suggesting a gradual transition from lizard-like ancestors. This evidence supports the theory that snakes evolved from burrowing lizards.

- ~80-100 million years ago, Late Cretaceous: Evolution of Venom

Molecular studies indicate that venomous snakes and some lizards, such as Heloderma (the Gila monster), evolved toxic salivary proteins during this period. Venom became a critical adaptation, aiding in predation and survival.

- ~85–66 million years ago, Late Cretaceous: Dominance of Mosasaurs

Mosasaurs, large marine squamates, emerged as apex ocean predators during the Late Cretaceous. Fossil evidence suggests that mosasaurs evolved from semi-aquatic ancestors similar to modern monitor lizards, gradually adapting to a fully marine lifestyle.

- ~66 million years ago: Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) Mass Extinction

The asteroid impact that marked the end of the Cretaceous period caused a mass extinction, wiping out non-avian dinosaurs, mosasaurs, and many squamate species. However, some squamate lineages survived and diversified in the new ecological landscape.

- ~50–30 million years ago, Eocene: Expansion of Modern Squamates

The Eocene epoch saw the rapid diversification of modern squamates, including geckos, iguanas, skinks, and snakes. During this time, various adaptations emerged, such as arboreal (tree-dwelling) and fossorial (burrowing) lifestyles, allowing squamates to thrive in different environments.

- ~25–10 million years ago, Miocene: Evolution of Advanced Snakes

During the Miocene, major snake lineages evolved into specialized groups. Boidae (boas) and Pythonidae (pythons) developed large constrictor species, while Elapidae (cobras, mambas) and Viperidae (vipers, rattlesnakes) became highly specialized venomous snakes, further shaping the ecological roles of squamates worldwide.

Where does Squamata live?

Squamata reptiles are found on every continent except Antarctica, showcasing their incredible adaptability to diverse environments. They thrive in various habitats, from urban areas and grasslands to mountains, deserts, and rainforests. Tropical regions and islands stand out as biodiversity hotspots, providing abundant food, suitable habitats, and unique conditions that foster endemic species.

Madagascar, the world’s fourth-largest island, is home to many endemic Squamata species, including the peculiar Leaf-tailed Geckos (Uroplatus spp.) and the vibrant Panther Chameleon (Furcifer pardalis). Over millions of years, these reptiles have adapted to the island’s varied habitats, from arid woodlands to lush rainforests.

What are the behaviors of Squamata?

The behaviors of Squamata are expressed through fascinating aspects such as feeding mechanisms, locomotion, communication, defense mechanisms, social behaviors, and reproduction. These behaviors highlight their adaptability and survival strategies in diverse habitats.

- Feeding Mechanisms: Squamates employ varied feeding strategies, from the foraging habits of green iguanas to the ambush tactics of vipers. Their diets range widely, including insects, plants, and small animals.

- Locomotion: Movement strategies include lizards’ agile quadrupedal motion and snakes’ serpentine or sidewinding techniques, adapted to environments like forests, deserts, or tight spaces.

- Communication: Squamates communicate through visual displays (e.g., color changes), chemical cues via pheromones, and auditory signals such as hissing. These methods serve territorial, reproductive, and defensive purposes.

- Defense Mechanisms: Camouflage, mimicry, venom, and tail autotomy are common strategies. For instance, geckos use camouflage, while snakes like cobras rely on venom or visual intimidation.

- Social Behaviors: Squamates exhibit territoriality and complex courtship, such as anoles’ throat pouch displays and cobras’ hood spreading.

- Reproduction: Squamata reproduction includes egg-laying (oviparity) and live birth (viviparity), with variations like parental care or independent hatchling survival.

Let’s start by diving into Feeding Mechanisms, showcasing Squamata’s adaptive dietary strategies.

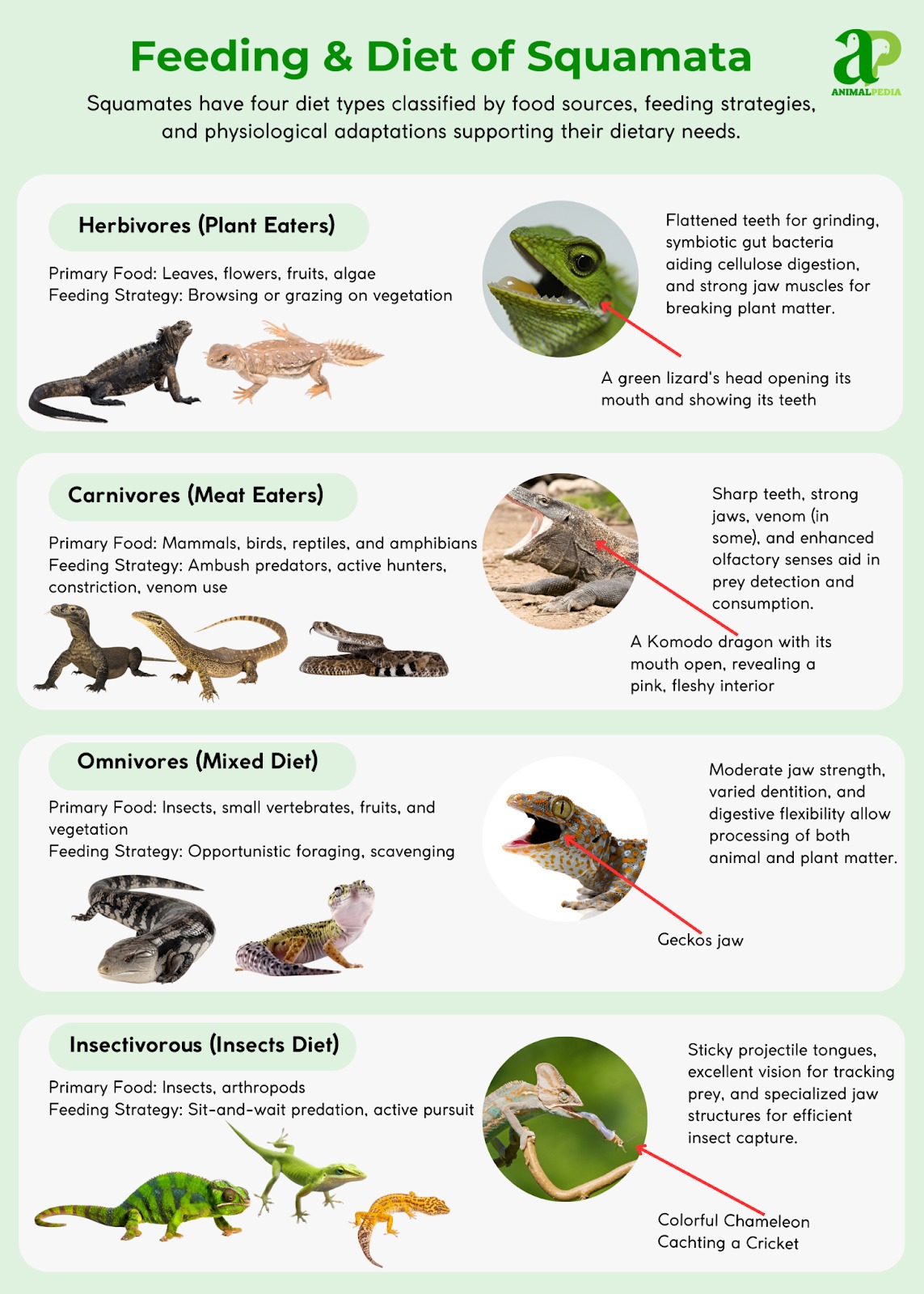

Diet and Feeding mechanism

Diets of Squamates range from herbivory to carnivory. Some species are strict herbivores, such as iguanas, which primarily consume leaves, while others, like spiny-tailed lizards, feed on desert vegetation, flowers, and fruits. These herbivorous squamates possess specialized gut microbiota that help break down cellulose.

Squamates have evolved diverse feeding mechanisms to enhance prey capture and consumption as follows.

- Cranial kinesis, highly developed in snakes, allows them to swallow large prey, while monitor lizards use moderate flexibility for a stronger grip.

- Venom evolution aids predation, with elapids using neurotoxins for paralysis and vipers relying on hemotoxins for tissue destruction.

- Constriction, seen in boas and pythons, applies immense pressure to induce circulatory arrest.

Squamates also employ different hunting strategies, with sit-and-wait predators like vipers, chameleons, and geckos ambushing their prey, while active foragers, such as monitor lizards and racer snakes, continuously search for food.

Locomotion

Squamata have developed 2 locomotion strategies, limbed and limbless to adapt to their environments. Their movement is influenced by body shape, the presence or absence of limbs, and external conditions.

- Limbed Locomotion

There are four styles of moving using their well-developed limbs as follows.

- Quadrupedal Walking & Running: Lizards move using a lateral undulation of the spine, coordinated with leg movement. Faster speeds often involve a bipedal gait (e.g., basilisk lizards).

- Bipedal Running: Some lizards run on their hind legs, often to escape predators.

- Climbing & Clinging: Arboreal lizards have specialized toe pads with microscopic setae that allow them to adhere to smooth surfaces.

- Gliding: Flying lizards use extended rib-supported flaps to glide between trees.

Snakes and some legless lizards have evolved five unique movement methods as follows.

- Lateral Undulation (Serpentine Movement): The most common and efficient mode, where the body forms S-shaped waves that push against the ground or water.

- Sidewinding: Used by desert-dwelling species (e.g., sidewinder rattlesnakes) to move across loose, shifting sand with minimal surface contact.

- Concertina Movement: Used in confined spaces like tunnels, where the body contracts and extends in sections.

- Rectilinear Movement: Slow, caterpillar-like movement using vertical lifting of belly scales; used by large snakes like pythons.

- Burrowing & Sand Swimming: Some species (e.g., sand boas) move through loose sand using wave-like movements.

Furthermore, several Squamata species have adapted to aquatic environments. Water-dwelling snakes, such as sea snakes, and semi-aquatic lizards utilize lateral undulation to propel through water. Basilisk lizards employ rapid leg movements and specialized foot fringes to run across water, exploiting surface tension and velocity.

Communication

Communication of Squamates primarily relies on visual, chemical, tactile, and acoustic signals, for social interactions, mating, territorial defense, and predator avoidance.

- Visual Communication: Includes body movements (head bobbing, push-ups, tail displays) and color changes to signal dominance, aggression, or mating readiness. Some species expand frills or display eye spots for intimidation.

- Chemical Communication: Relies on pheromones and scent marking from specialized glands to attract mates, establish territories, and detect conspecifics. Snakes and some lizards use their vomeronasal organ (Jacobson’s organ) to process chemical cues.

- Acoustic Communication: Less common but includes vocalizations such as clicks, chirps, hisses, and rattles for territorial defense, mate attraction, and warning signals.

- Tactile Communication: Involves physical interactions like courtship biting, tail whipping, and combat grappling for mating and dominance establishment.

Defense mechanisms

Squamates employ four defense mechanisms, including behavioral, morphological, physiological, and chemical categories to evade predators and increase survival.

- Morphological defenses involve physical traits that deter predators. Cryptic coloration, or camouflage, allows squamates to blend into their environment, making them less visible. Some species use aposematism, displaying bright warning colors to signal toxicity or unpalatability. Others rely on body inflation and posturing, such as spreading hoods or extending frills, to appear larger and more intimidating.

- Behavioral defenses include specialized actions that reduce predation risk. Many squamates engage in thanatosis (playing dead), tricking predators into losing interest. Caudal autotomy (tail shedding) allows lizards to escape while their detached tail distracts attackers. Some species evade threats through burrowing or rapid escape, using speed or sand-diving to avoid capture.

- Physiological and chemical defenses provide additional protection. Venomous species deter predators with toxic bites, while others use blood-squirting or foul-smelling cloacal secretions to repel threats. Snakes and lizards may also utilize acoustic and visual distractions, such as rattling, hissing, or flashing bright body parts, to startle predators and create an opportunity for escape.

- Mimicry and deception further enhance survival. Some harmless species mimic venomous or toxic animals to deter predators, a strategy known as Batesian mimicry. Others, like certain snakes, feign death with dramatic body postures and foul odors to mislead attackers.

Together, these defense mechanisms showcase the adaptability of squamates, allowing them to thrive across diverse habitats despite constant predation pressures.

Social Behavior

Squamates, once thought to be mostly solitary, actually show 4 common social behaviors, from defending territories to forming family groups and even cooperating.

- Most are solitary, interacting mainly for mating or defending their space. However, some lizards, like skinks, live in family groups, while others, like garter snakes, hibernate together for warmth.

- Territoriality is common, with males using visual displays (head bobbing, push-ups, dewlap extensions) or physical fights (biting, tail whipping) to defend their space. Some species form social hierarchies, where bigger or more colorful individuals dominate.

- Mating behaviors vary—many males compete for multiple females (polygyny), while a few, like shingleback skinks, stay with one partner (monogamy). Courtship involves visual signals, pheromones, and physical contact to attract mates.

- Aggression and conflict happen over territory and mates, with males wrestling or displaying dominance. Some squamates, though, avoid fights by showing submissive gestures.

These behaviors show that squamates are more socially complex than once believed, adapting their interactions based on their environment and needs.

Reproduction

Most squamates reproduce sexually, with males and females engaging in internal fertilization. Polygyny—where one male mates with multiple females—is the most common system, though some species, like shingleback skinks, form monogamous pair bonds. Additionally, certain species can reproduce asexually through parthenogenesis, a process in which females produce offspring without males. This allows for rapid population growth but reduces genetic diversity.

Internal fertilization is made possible by hemipenes, specialized male reproductive organs. Some females can store sperm for months or even years, enabling delayed fertilization and providing flexibility in reproductive timing.

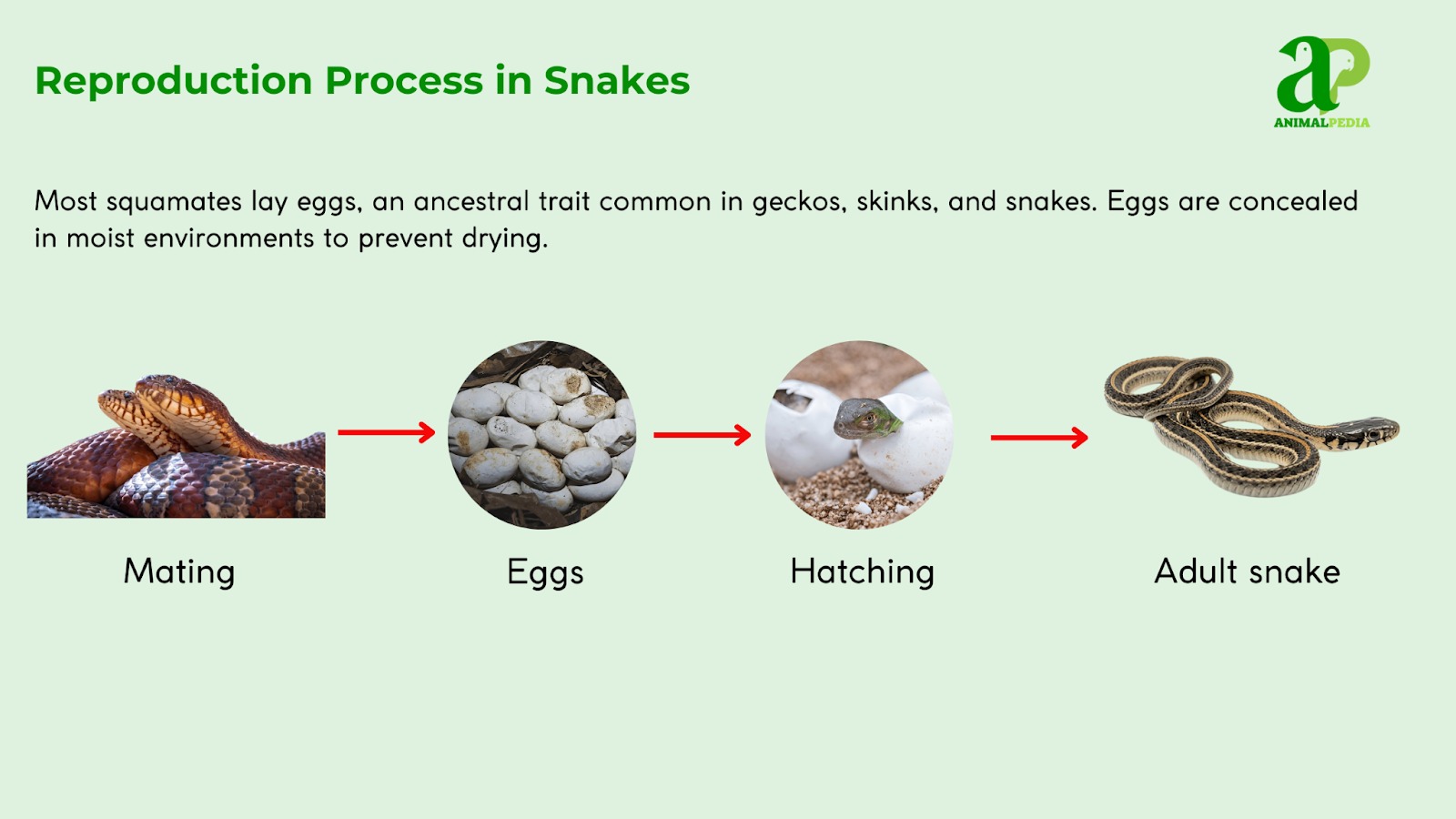

Squamates exhibit three reproductive modes as follows.

- Oviparity (egg-laying): The most common strategy, allowing large clutches while minimizing maternal energy investment in pregnancy.

- Viviparity (live birth): More common in species from colder or unpredictable environments, offering protection to developing offspring inside the mother’s body.

- Ovoviviparity (a hybrid strategy): Eggs develop internally but hatch inside or immediately after being laid, balancing protection with energy conservation.

Parental care is rare in squamates. However, some species, like pythons, guard their eggs and regulate temperature through shivering thermogenesis. Certain skinks even raise their young in family groups.

Environmental factors also shape reproduction. Some species exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD), where incubation temperatures influence offspring sex. Additionally, reproductive cycles are often seasonal, aligning with food availability and climate conditions.

What is the relationship between Squamata and Humans?

Squamates (lizards and snakes) have a complex relationship with humans, impacting ecosystems, economies, medicine, and culture. While some species provide ecological and economic benefits, others are feared, exploited, or threatened by human activities.

- Ecological Importance

Squamates play a crucial role in pest control, food webs, and ecosystem balance. Many species help reduce insect and rodent populations, preventing crop damage and disease spread. For example, snakes can consume 3,000–5,000 rodents per hectare per year in agricultural areas. They also serve as prey for birds, mammals, and other reptiles, contributing to biodiversity. Additionally, their presence acts as a bioindicator, reflecting habitat health and pollution levels.

- Economic and Commercial Impact

Squamates are valuable in the pet trade, leather production, and ecotourism. They make up 80% of the global reptile pet trade, with the U.S. market alone valued at $1.4 billion annually. The leather and meat trade generates billions, with python skin in high demand for luxury fashion brands. Ecotourism also plays a role, with attractions like Komodo National Park and the Galápagos Islands generating millions in revenue.

- Cultural and Religious Significance

Squamates have been symbols of power, fertility, and danger in various cultures. In Hinduism, Nagas are sacred deities, while in Christianity, the serpent represents temptation. Despite their significance, fear and superstition persist, with 30% of people worldwide experiencing ophidiophobia (fear of snakes). In some cultures, snakes are killed due to myths, while others, like Thailand, see geckos as symbols of good luck.

- Threats from Human Activities

Squamate populations face severe threats, primarily from habitat destruction, climate change, and the illegal wildlife trade. Deforestation and urbanization have placed 30% of species at risk, with areas like the Amazon losing 17% of habitat. Climate change disrupts reproductive cycles, as seen in bearded dragons, where extreme temperatures produce 98% female offspring. The illegal reptile trade, valued at $2 billion annually, further endangers many species.

- Human-Wildlife Conflict

Many squamates are persecuted due to fear or resource competition. Snakebites cause up to 138,000 human deaths annually, with India recording 58,000 deaths per year. Meanwhile, large monitor lizards and pythons prey on livestock, leading to retaliatory killings.

- Conservation and Coexistence

Efforts to protect squamates include wildlife reserves, education programs, and eco-tourism initiatives. Protected areas now cover over 2 million square kilometers, and community conservation projects in places like India and Costa Rica help relocate venomous snakes and promote awareness.

Squamates are essential to ecosystems and economies, but their survival depends on human understanding, conservation, and sustainable practices.

Are Squamata going endangered?

Yes, Squamata faces significant conservation challenges despite its vast diversity. Habitat loss and fragmentation caused by urbanization, deforestation, and agriculture are primary threats, compounded by climate change disrupting breeding, food availability, and habitats.

Invasive species, such as rats and mongooses, introduce predators and competitors, further destabilizing populations, particularly on islands. Overexploitation for bushmeat, the pet trade, and traditional medicine also endangers many species.

Efforts to support conservation include establishing protected areas like national parks and reserves to safeguard habitats. International agreements, such as CITES, regulate the trade of endangered Squamata species, while captive breeding programs help preserve genetic diversity and provide individuals for reintroduction. Habitat restoration, sustainable land practices, and managing invasive species mitigate habitat loss and fragmentation.

Community involvement is vital. Outreach and education programs promote sustainable practices, fostering local participation in conservation. Initiatives like ecotourism provide financial incentives, encouraging long-term protection of Squamata and their ecosystems.

How does Squamata affect humans and the environment?

Squamata plays essential ecological roles but can pose risks to human health and environmental balance. A primary concern is disease transmission, as reptiles carry Salmonella bacteria, responsible for about 6% of salmonellosis cases in the U.S., particularly among young children.

Venomous snakes also contribute to roughly 125,000 deaths annually, primarily in developing regions with limited access to antivenom. Invasive Squamata species disrupt ecosystems, such as the Burmese python in Florida’s Everglades, which has drastically reduced native wildlife populations.

Effective solutions are in place to address these challenges. Public health campaigns promoting hygiene when handling reptiles have lowered disease transmission by 30% in targeted areas. Region-specific antivenoms have reduced snakebite fatalities by 50% in treated communities.

Environmental programs, like Florida’s python removal initiative, have removed over 17,000 invasive snakes since 2017, aiding ecosystem recovery. Stricter exotic pet trade regulations have cut the introduction of invasive species by 40% in monitored regions, showcasing the success of preventive measures.

FAQs

Are snakes and lizards the only members of Squamata?

Of course, not all Squamata are snakes or lizards. Indeed, the Squamata order comprises a variety of reptiles, including worm lizards (Amphisbaenia) and tuatara (Rhynchocephalia). However, snakes and lizards are the most well-known members of this order. The bulk of the diversity of Squamata species is, nevertheless, represented by snakes and lizards.

Why are Squamata species important for ecosystems?

In the natural world, squamata species are essential predators, prey, and ecosystem builders. They help regulate food webs, cycle nutrients, control insect and small vertebrate populations, and function as markers of ecosystem health.

How can I help conserve Squamata species?

By supporting conservation organizations, promoting habitat protection and sustainable land management techniques, minimizing their ecological footprint, refraining from acquiring pets captured in the wild, and teaching others about the value of biodiversity conservation, individuals can help conserve Squamata.

Do all Squamata species lay eggs?

No, although a large number of Squamata species lay eggs, some also give birth to live offspring. Different species have different reproductive strategies, and environmental elements, including habitat, climate, and evolutionary history, can all impact them.

This article provides you with useful information about Squamata, including its definition, characteristics, classification, behaviors, and facts. With over 10,000 species, Squamates are found worldwide, exhibiting a wide range of behaviors and adaptations. Most are ectothermic (cold-blooded) and vary greatly in size, diet, and habitat. Please visit Animal Pedia if you want to explore the diversity of animals all over the world.