Boa snakes belong to the Boidae family, encompassing over 50 species with diversity. Their powerful, muscular bodies covered in smooth scales display colors ranging from vibrant greens to subdued browns, with distinctive patterns that enhance camouflage. The Boa constrictor, particularly notable, reaches 6–10 feet in length, with exceptional specimens growing to 13 feet and weighing 60 pounds. These reptiles inhabit regions throughout Central and South America, with subspecies like Boa constrictor imperator thriving on isolated islands such as Honduras’ Cayos Cochinos. Their triangular heads and specialized heat-sensing pits are key identifying features, enhancing their ability to detect prey in low-light environments.

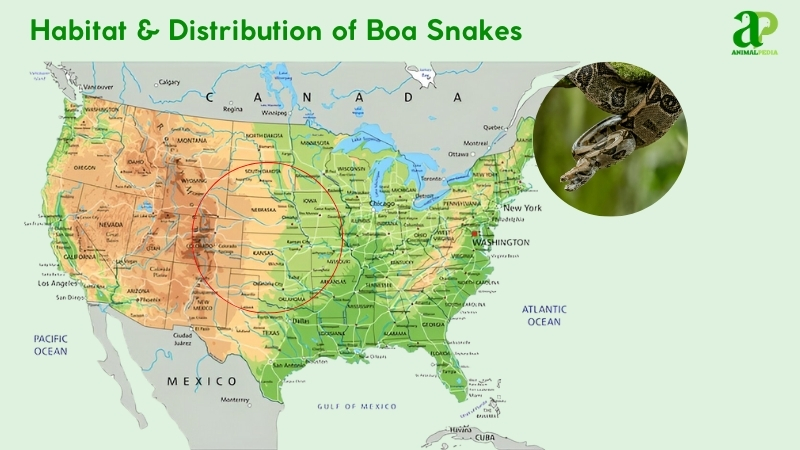

These constrictors adapt to diverse ecosystems, from dense rainforests to arid savannas. The common Boa constrictor favors humid forest habitats, while Dumeril’s boa (Acrantophis dumerili) survives in Madagascar’s dry regions. They show habitat versatility, occupying various altitudes, often establishing territories near water sources for hunting. Juvenile boas frequently climb trees, while adults primarily navigate ground level. Island populations, such as those in Dominica, exhibit distinct characteristics from continental specimens due to geographic isolation, highlighting their evolutionary adaptability.

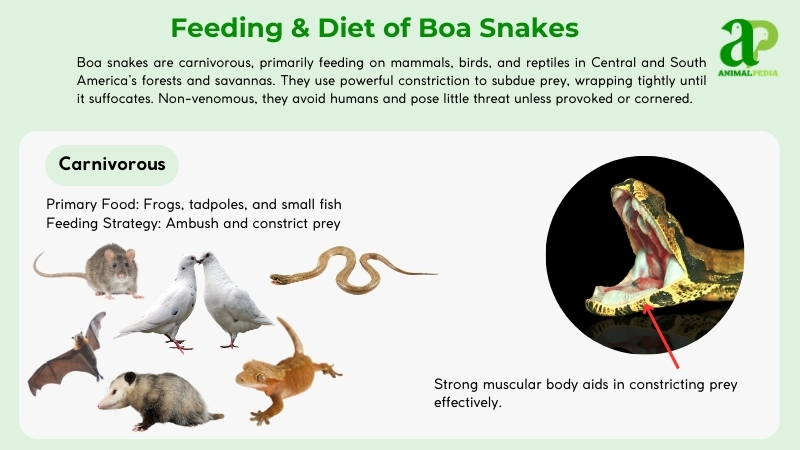

As apex predators, boas function as non-venomous constrictors within their food webs. They ambush mammals, birds, and reptiles, with their diet varying by size—smaller individuals target rodents, while larger specimens prey on animals as big as capybaras. Typically solitary hunters, they interact mainly during breeding seasons and avoid human contact, though they may defend themselves when threatened. Their nocturnal behavior and specialized heat-detection organs ensure hunting precision, solidifying their ecological dominance.

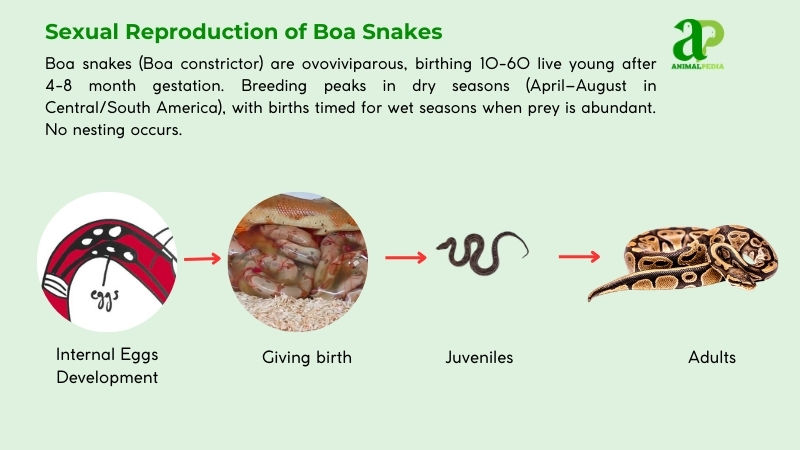

Reproduction peaks during dry months, April through August. Being ovoviviparous, females internally incubate eggs for 4–8 months before delivering 10–60 live young. Newborns measure 15–20 inches and immediately function independently. Sexual maturity occurs at 2–3 years, with lifespans extending 20–30 years in favorable conditions. These reptiles provide no parental care—offspring disperse immediately after birth.

This examination reveals boa snakes’ striking morphology, ecological adaptability, efficient predation strategies, and specialized reproductive traits. From their island-specific adaptations to their crucial ecological functions, boas represent fascinating subjects for both herpetology enthusiasts and conservation biologists studying evolutionary adaptation and predator-prey dynamics.

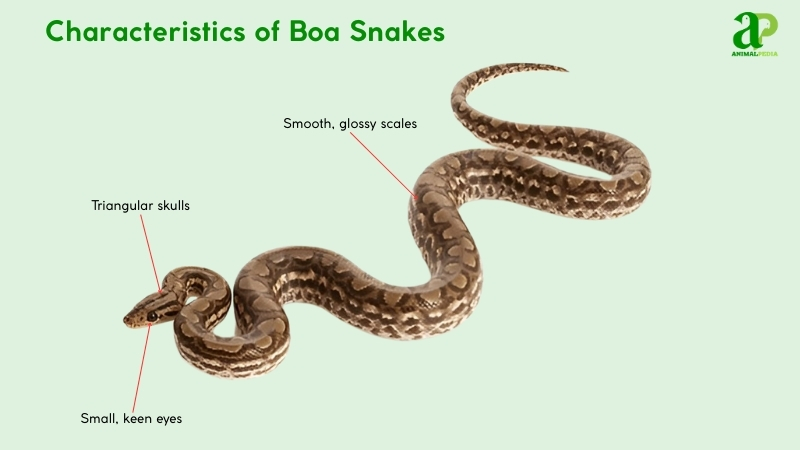

What Do Boa Snakes Look Like?

Boa snakes have strong, round bodies that narrow from head to tail. Their smooth scales feel glossy to touch, helping them move silently through their environments. Colors vary widely—from rich greens to earth-toned browns—with distinct patterns like saddles or diamonds that provide natural camouflage.

The common boa constrictor (Boa constrictor) typically shows tan coloration with dark patches, while the emerald tree boa (Corallus caninus) displays striking green hues. These natural markings help distinguish boas from pythons, which have rougher scales and less consistent patterns.

The head of a boa is triangular with small, sharp eyes containing vertical pupils—an adaptation for hunting at night. Heat-sensing pits line their mouths, detecting warm-blooded prey with precision that colubrid snakes lack. Their forked tongues collect chemical information from their surroundings.

Without the limbs or claws seen in lizards, a boa’s body moves with flexibility. In tree-dwelling species, the short, prehensile tail functions as a fifth limb for gripping branches—unlike the heavier tails of ground-dwelling pythons. These distinctive traits—glossy scales, heat-detection systems, and grasping tails—combine natural beauty and hunting efficiency in these reptiles.

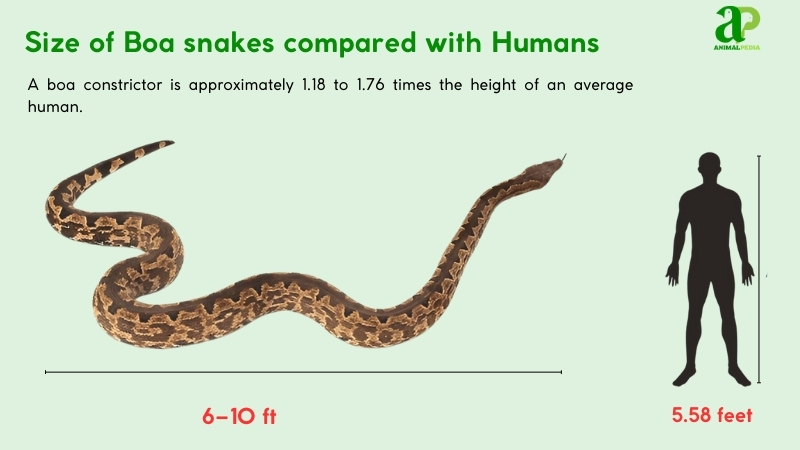

How Big Do Boa Snakes Get?

Boa snakes, notably Boa constrictor, average 6–10 feet (1.8–3 meters) in length and weigh 20–60 pounds (9–27 kg). Females typically outsize males, attaining greater length and weight due to reproductive demands. Their muscular, cylindrical bodies vary by habitat, with island subspecies often smaller. These measurements reflect healthy adults in diverse ecosystems, from rainforests to savannas.

The largest recorded Boa constrictor stretched 13 feet (4 meters) and weighed 99 pounds (45 kg), as documented in Suriname by Reed and Rodda (2021). Adults generally measure 6–10 feet (1.8–3 meters) from snout to tail. Sexual dimorphism is evident: females average 8–10 feet (2.4–3 meters) and 40–60 pounds (18–27 kg), while males hit 6–8 feet (1.8–2.4 meters) and 20–40 pounds (9–18 kg).

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 6–8 ft (1.8–2.4 m) | 8–10 ft (2.4–3 m) |

| Weight | 20–40 lbs (9–18 kg) | 40–60 lbs (18–27 kg) |

What Are The Unique Physical Characteristics Of The Boa Snakes?

Boa snakes within the Boidae family have heat-sensing pits, a feature missing in most snake species. These specialized organs line their upper lips, detecting infrared radiation from warm-blooded prey. This lets them hunt accurately even in darkness. This adaptation sets boas apart from colubrids and vipers, which use different sensory systems for hunting.

Their muscular, prehensile tails form another distinctive characteristic, especially in tree-dwelling species like the emerald tree boa. These tails grip branches securely, unlike ground-dwelling snakes. This adaptation supports their arboreal lifestyle and hunting strategy.

Research by Burghardt and Greene (2018) shows these thermal receptors contain trigeminal nerve endings sensitive to temperature shifts as small as 0.002°C. Boas use this ability to create thermal maps of their environment, essential for night hunting. Reed and Rodda (2021) documented that their prehensile tails exhibit unique vertebral flexibility, uncommon in other snakes. These specialized traits—heat detection and gripping tails—give boas exceptional adaptability, highlighting their distinct evolutionary path.

In understanding the unique traits of this species, it’s essential to explore the general squamata characteristics that define the group as a whole.

How Do Boa Snakes Sense Their Environment With Their Unique Features?

Boa snakes hunt with infrared-sensing pits along their upper lips. These specialized organs detect prey’s body heat, allowing precise strikes even in darkness. This thermoreception, unique to the Boidae family, gives boas a critical advantage when hunting in dense rainforest habitats and other low-light environments. Research by Burghardt and Greene (2018) confirms these heat-sensing organs can detect temperature differences as small as 0.003°C, making boas extraordinarily efficient predators.

Multiple sensory systems work together to enhance the boa’s environmental awareness. Their vertical-pupil eyes capture available light effectively, while their bifurcated tongue collects airborne particles when flicked. This chemosensory information travels to the Jacobson’s organ in the roof of the mouth, creating a three-dimensional scent map. Scale mechanoreceptors detect subtle ground vibrations, and specialized jaw structures sense nearby movements. This integrated sensory network allows boas to function as apex predators across diverse ecosystems from tropical forests to arid regions.

Anatomy

Boa snakes, powerful constrictors of the Boidae family, have evolved specialized anatomical systems for survival. Their distinct body structure enables them to thrive across diverse habitats, from dense rainforests to open savannas.

- The respiratory system features asymmetrical lungs, with the right lung dominant for oxygen absorption. Their glottis controls airflow efficiently during constriction events, supporting their low-metabolism lifestyle without compromising oxygen intake.

- Boas maintain a three-chambered heart that powers their circulatory system, delivering oxygen to muscles during prolonged hunting periods. Blood flow adapts during constriction, maintaining vital organ perfusion when subduing prey.

- Their digestive apparatus includes an expandable stomach and potent digestive enzymes. This allows boas to consume prey whole, sometimes exceeding their own body diameter. Digestion may continue for 7-10 days, conserving energy through infrequent feeding cycles.

- The excretory system consists of paired kidneys that produce concentrated uric acid, minimizing water loss. This adaptation serves boas in both arid and humid environments, maintaining hydration during extended fasting periods.

- A sophisticated neural network coordinates their hunting behaviors. The brain processes information from heat-sensing pits while spinal nerves control the precise muscular contractions needed for lethal constriction. These neural pathways ensure accurate environmental responses, essential for predatory success.

These interconnected biological systems reveal the evolutionary adaptations of boa constrictors, making them both formidable hunters and fascinating subjects for comparative vertebrate anatomy.

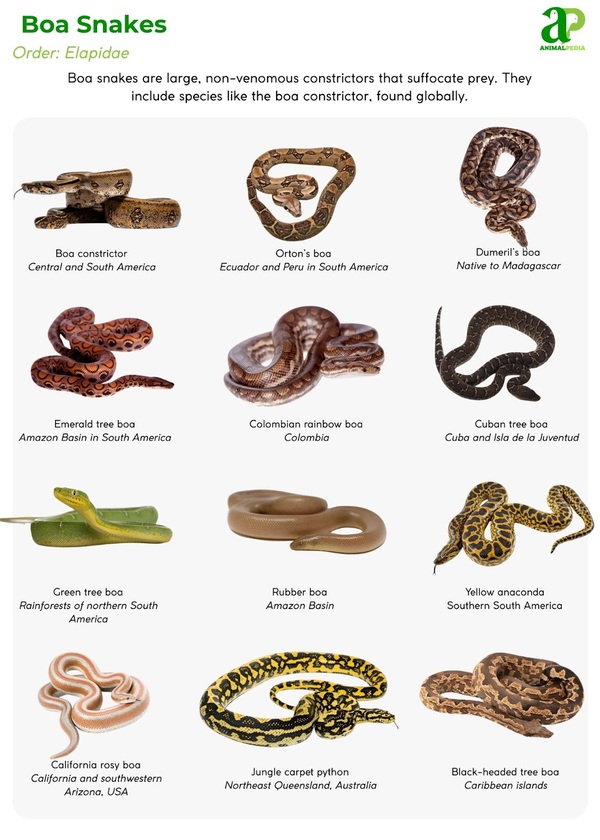

How Many Types Of Boa Snakes?

Boa snakes encompass over 50 species within the Boidae family, a diverse group of non-venomous constrictors. Key species include Boa constrictor (common boa) and Corallus caninus (emerald tree boa), each adapted to distinct ecological niches. Their classification, grounded in morphological and genetic traits, ensures precise taxonomic organization, vital for understanding their evolutionary divergence.

Carl Linnaeus laid the foundation for this classification in the 18th century, which has since been refined by modern phylogenetics. Recent studies integrate DNA sequencing to clarify relationships within Boidae, distinguishing boas from pythons based on pelvic spur presence and head scale patterns. This system, per Reynolds and Henderson (2018), supports accurate species delineation.

The branch diagram simplifies Boidae taxonomy:

- Family: Boidae

- Genus: Boa, Corallus, Acrantophis

- Species: Boa constrictor, Corallus caninus, Acrantophis dumerili

- Genus: Boa, Corallus, Acrantophis

Here is some outstanding types of Boa Snakes with its distribution:

Special cases include island subspecies such as Boa constrictor imperator on Cayos Cochinos, which exhibit dwarfism due to isolation, unlike their mainland counterparts. Another anomaly, the Eryx species, once classified as boas, now form a separate subfamily (Erycinae) due to distinct burrowing adaptations, highlighting classification complexity.

Where Do Boa Snakes Live?

Boa snakes live throughout Central and South America. Boa constrictor species dominate Amazon rainforests, Andean foothills, and isolated habitats like Honduras’ Cayos Cochinos. In contrast, Dumeril’s boa (Acrantophis dumerili) inhabits Madagascar’s western dry forests. These reptiles thrive across diverse ecosystems ranging from humid tropical jungles to dry savannas where prey is abundant.

These constrictors prefer environments with dense vegetation and reliable water sources, which support their ambush-hunting strategy and temperature-regulation needs. The tropical climate zones perfectly match their ectothermic physiology, while varied elevations have driven adaptive specialization.

Unlike terrestrial pythons, arboreal boas such as the emerald tree boa (Corallus caninus) have evolved to exploit forest canopies. Paleontological evidence indicates boas have occupied these regions for millions of years without significant range shifts, demonstrating ecological stability. Island populations exhibit notable genetic adaptations, confirming their perfect ecological niche fit.

How Do Seasonal Changes Affect Their Behavior?

Boa snakes adapt behaviors across two main seasons: wet (November–April) and dry (May–October), driven by ecological shifts in their tropical habitats.These wet–dry season shifts mirror broader patterns discussed in snake behaviors.

- Wet Season: Boas increase hunting, targeting abundant prey like rodents and birds. Activity peaks at night, with females preparing for gestation, leveraging humidity for thermoregulation.

- Dry Season: Hunting slows as prey scatters; boas conserve energy, often resting in shaded areas. Mating intensifies as males seek females, and parturition occurs late in the season.

These shifts optimize survival, aligning activity with resource availability and reproductive cycles.

What Are The Behaviors Of Boa Snakes?

Boa snakes exhibit complex behaviors that help them survive in diverse habitats. As non-venomous constrictors, they rely on stealth and strength, and they showcase unique patterns in feeding, movement, and social interactions, shaped by their ecological roles.

- Feeding Habits: Boas ambush prey, constricting mammals and birds. Their diet adapts to size, targeting larger animals as they grow.

- Bite & Venomous: Lacking venom, boas use sharp teeth to grasp prey. Bites are non-lethal, used defensively if threatened.

- Daily Routines and Movements: Nocturnal, boas rest by day, hunting at night. They move slowly, conserving energy for ambushes.

- Locomotion: Boas slither with rectilinear motion, using muscles for grip. Arboreal species climb, aided by prehensile tails.

- Social Structures: Solitary except during mating, boas avoid interaction. Males compete briefly for females.

- Communication: Boas use pheromones and tongue-flicking to sense mates or rivals. Physical cues signal during rare encounters.

To dive deeper, their feeding habits reveal a masterful predatory strategy that blends patience with power.

What Do Boa Snakes Eat?

Boa snakes are strict carnivores, preying on mammals, birds, and reptiles, with rodents and bats as favored targets in Central and South America’s forests. Non-venomous, they avoid humans, using constriction for prey, not defense.

- Diet by Age

Diet shifts with growth to match energy needs. Hatchlings (0–6 months) eat small rodents and lizards, supporting rapid development. Juveniles (6 months–2 years) target medium rodents and birds, perfecting ambush skills. Subadults (2–3 years) pursue larger rodents, strengthening constriction. Adults (3+ years) consume capybaras and monkeys, thriving in diverse habitats like Amazon rainforests.

- Diet by Gender

Males and females have identical diets, focusing on similar prey, such as rodents. Both employ constriction and swallow prey whole, with females occasionally eating more during gestation.

- Diet by Seasons

Seasons alter feeding. In the wet season (November–April), abundant prey drives frequent hunts. In the dry season (May–October), scarcer prey leads to reduced feeding, with boas resting in shaded areas to conserve energy.

How Do Boa Snakes Hunt Their Prey?

Boa snakes, like the boa constrictor and rainbow boa, hunt with deadly precision. They strike first, seizing prey with backward-curved teeth designed for gripping without escape.

After capture, boas employ constriction – wrapping muscular coils around the prey and tightening with each exhale. This doesn’t crush the victim but interrupts blood flow, causing rapid cardiac arrest. The entire process often takes minutes, not hours, as commonly believed.

These ambush predators use heat-sensing labial pits along their mouths to detect warm-blooded prey even in darkness. Boas don’t chase – they wait motionless for the perfect moment, sometimes hanging from branches to strike downward at passing animals.

Alimentary adaptation enables these serpents to consume prey much larger than their head diameter. Their hinged jaws and elastic skin allow them to swallow animals whole, while powerful digestive enzymes efficiently break down bones and tissues. After a substantial meal, a boa may not need to feed again for weeks.

Are Boa Snakes Venomous?

When Are Boa Snakes Most Active During The Day?

Boa Snakes are typically most active at night, showing increased activity levels under the veil of darkness. While you’re asleep, these reptiles are out exploring and hunting for prey.

Boa Snakes are nocturnal creatures, using their sharp senses to move in the dark and find food. Picture the thrill of observing these graceful animals gliding through the shadows, their robust bodies perfectly suited for silent movements under the moon’s glow.

It’s during these night adventures that Boa Snakes demonstrate their exceptional hunting prowess, relying on their constriction abilities to overpower their unsuspecting targets.

How Do Boa Snakes Move On Land And Water?

Boa snakes move with distinct locomotive patterns both on land and in water. On land, they employ lateral undulation—their primary movement method, in which muscular contractions create S-shaped waves that push against ground surfaces. These constrictors use their ventral scales as anchor points, generating forward thrust through friction against terrain irregularities.

Rectilinear progression appears when boas travel slowly across smooth surfaces. Their specialized ventral scales function like tank treads, with alternating muscle contractions creating a straight-line crawl. This technique allows silent movement, ideal for hunting.

In arboreal environments, boas utilize concertina locomotion, alternating between anchoring their body and extending forward sections to navigate branches. Their prehensile tails provide crucial support during climbing activities.

When swimming, these serpents execute lateral undulation with efficiency. Their streamlined morphology and powerful axial musculature propel them through water with minimal resistance. Boas can maintain buoyancy by trapping air in their lungs, allowing them to float partially submerged while keeping their heads above water for extended periods.

These diverse movement capabilities demonstrate the biomechanical adaptability that has made boas successful predators across varied habitats from the Neotropical rainforests to riparian environments throughout the Americas.

Do Boa Snakes Live Alone Or In Groups?

Boa constrictors live alone. These reptiles prefer solitary lifestyles throughout most of their lives. They seek their own territory, hunt independently, and avoid other snakes except during mating season. Solitary behavior benefits boas in several ways. Living alone lets them focus on survival without competition from other snakes. This independence allows each constrictor to develop hunting skills tailored to its specific habitat, whether tropical forests, grasslands, or semi-arid regions.

When hunting, boas rely on stealth and patience. They detect prey through heat-sensing pits and chemical cues. After striking, they use powerful muscular coils to subdue victims—a technique that works best for a lone predator rather than a group.

The only time boa snakes typically interact is during breeding season. Males will seek out females, sometimes competing with other males, but this social interaction is temporary. After mating, females return to solitary lives, even when carrying offspring.

Young boas receive no parental care after birth. They disperse immediately, beginning solitary lives as miniature versions of their parents, instinctively equipped for independent survival.

How Do Boa Snakes Communicate With Each Other?

Boa Snakes communicate mainly through body language and pheromones. They use various body movements to express emotions and intentions. When feeling threatened, they might coil tightly, hiss loudly, or even strike to show aggression.

Conversely, a relaxed boa snake can be observed basking under the sun, moving slowly, and flicking its tongue to sense scents and pheromones in the air. Pheromones are crucial for communication in boas, as they help detect each other’s presence, reproductive status, and other essential information.

How Do Boa Snakes Reproduce?

Boa constrictors reproduce through ovoviviparity, developing embryos internally rather than laying eggs. During the dry season (May–October), males track females by following pheromone trails. Males court females with tongue flicks and body wrapping, sometimes fighting other males for access. Mating lasts several hours to ensure successful fertilization.

After mating, female boas undergo a 4–8 month gestation period. They birth 10–60 live young, each measuring 15–20 inches (38–50 cm) and weighing 3–4 ounces (85–113 grams). Unlike oviparous reptiles, no external eggs or nests exist. The mother’s body provides protection throughout development. Environmental stress or poor nutrition can cause embryo reabsorption or stillbirths, particularly during drought conditions (Burghardt & Greene, 2018).

Post-reproduction, males return to solitary lives while females focus on pregnancy. Neonate boas emerge fully independent, hunting small prey such as lizards and rodents immediately after birth. They grow quickly, reaching sexual maturity at 2–3 years. Boa constrictors typically live 20–30 years in natural habitats, with females reproducing every 2–3 years. This reproductive strategy enhances offspring survival across diverse ecosystems from tropical rainforests to remote islands.

How Long Do Boa Snakes Live?

Boa snakes live 20–30 years on average in the wild, with lifespans reaching 40 years in captivity. Their life cycle includes rapid juvenile growth, maturity at 2–3 years, and breeding every 2–3 years for females.

Males and females share similar lifespans, though females may face higher mortality during gestation due to energy demands. Environmental factors such as predation and habitat quality influence longevity, and island populations sometimes outlive mainland ones due to fewer threats.

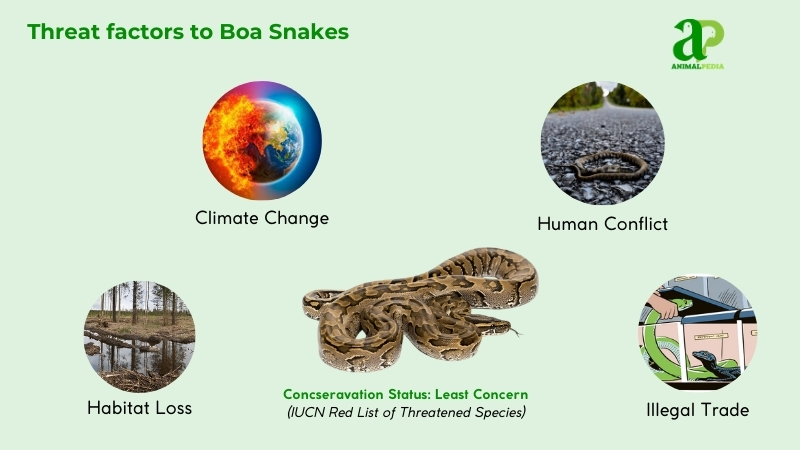

What Are The Threats Or Predators That Boa Snakes Face Today?

Boa constrictors face four major threats today: habitat destruction, climate shifts, wildlife trafficking, and human persecution. Natural predators primarily target young boas, including raptors, large mammals, and opportunistic reptiles. Human activities are their greatest survival challenge, disrupting entire ecosystems.

- Habitat fragmentation devastates boa populations. Rapid deforestation in the Amazon Basin and Central American rainforests eliminates crucial hunting territories, decreasing both prey abundance and shelter options. Isolated populations in heavily fragmented landscapes show alarming decline rates.

- Temperature fluctuations severely impact these ectothermic reptiles. Rising global temperatures disrupt prey availability and reproductive timing. Research indicates temperature-sensitive species like boas may lose up to 20% of their suitable habitat in vulnerable regions, affecting their physiological functions and survival rates.

- The exotic pet trade poses an existential threat. Poaching removes thousands of boas from wild populations each year, severely undermining genetic diversity. The CITES-listed species face particularly intense collection pressure, with B. c. imperator and B. c. constrictor subspecies suffering significant population declines.

- Human-wildlife conflict increases as development expands into boa territory. Vehicle collisions and deliberate killings from fear-based reactions reduce survival rates, especially for island-endemic subspecies with already limited ranges. Conservation efforts must address these anthropogenic threats to ensure the boa’s survival.

Threat factors to Boa Snakes

Predators vary by region. Jaguars and ocelots hunt adults in rainforests, while harpy eagles and hawks target juveniles. In Madagascar, fossas prey on Dumeril’s boa. Young boas face cannibalism from larger snakes, including conspecifics.

Human impact intensifies threats. Urban expansion fragments habitats, and poaching fuels black markets, with 80% of traded boas sourced illegally (Auliya et al., 2016). Conservation efforts, like protected reserves, aim to mitigate these pressures, but enforcement lags in remote areas.

Are Boa Snakes Endangered?

Most boa snake species aren’t endangered, but several face threats. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the common Boa constrictor as “Least Concern,” with healthy populations throughout Central and South America. However, isolated subspecies face greater risks. The Cayos Cochinos population of Boa constrictor imperator is “Vulnerable” due to habitat destruction and collection pressure. Similarly, Madagascar’s Dumeril’s boa (Acrantophis dumerili) is listed as “Vulnerable” due to forest clearing and wildlife trafficking.

Population estimates vary widely across the boa family (Boidae). Researchers believe Boa constrictor numbers reach the millions across their range, aided by their ability to thrive in diverse ecosystems (Reed & Rodda, 2021). Their adaptability to human-altered landscapes gives them resilience other reptiles lack. Yet island populations, such as the Pearl Island boa, likely number fewer than 10,000 individuals, with documented declines linked directly to human encroachment (Auliya et al., 2016).

The primary conservation threats to boa snakes include deforestation, agricultural expansion, and unsustainable harvest for the exotic pet trade. Their generally wide distribution provides a buffer against extinction for most species. Conservation initiatives focus on habitat protection, captive breeding programs, and trade regulation to safeguard the most threatened populations and ensure long-term survival of these iconic constrictors.

What Conservation Efforts Are Underway?

Boa snakes, particularly boa constrictors, face threats from habitat destruction and the exotic pet trade. These challenges have triggered targeted conservation initiatives worldwide. The Puerto Rican boa (Chilabothrus inornatus), once critically endangered, shows recovery through dedicated protection efforts.

Since the 1970s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Puerto Rican conservation groups have restored crucial ecosystems. Their work focuses on coastal forests and karst landscapes where these serpents thrive. Translocation programs began in the early 2000s, moving boas from development zones to protected areas. These efforts have boosted populations to approximately 30,000 boas island-wide, prompting its proposed delisting in 2022.

Legal protections form the backbone of boa conservation. The Endangered Species Act of 1973 shields native boas by outlawing hunting and habitat destruction. Internationally, the CITES Appendix II regulates the boa constrictor trade with strict export controls. In Florida, authorities manage non-native boa populations under the Lacey Act, which limits interstate transport to prevent the spread of invasive species.

Captive breeding programs have proven vital for threatened species. The Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust launched breeding initiatives for the keel-scaled boa in Mauritius during the 1980s. This program, combined with predator eradication targeting rats and feral goats, increased their numbers from just 60 specimens in 1976 to stable populations by 2018.

Conservation success stories include the Puerto Rican boa’s population rebound and the keel-scaled boa’s improved status to vulnerable. These victories showcase effective habitat-restoration techniques and public education campaigns led by organizations such as the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation.

These multifaceted approaches—combining legal frameworks, strategic relocations, and scientific breeding—ensure the survival of boas across their range. Conservation agencies and local trusts continue driving progress, safeguarding biodiversity through evidence-based interventions and community involvement.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Boa Snakes Change Color Like Chameleons?

Yes, boa snakes cannot change color like chameleons. Boas have fixed coloration; however, color patterns vary between species. Boas don’t have the ability to rapidly change color in response to their surroundings.

Do Boa Snakes Lay Eggs Or Give Birth To Live Young?

Boa snakes give birth to live young, and within their species, they boast diverse birthing techniques. Some surprise with live offspring, while others bring forth egg sacs. Boas excel at a variety of reproductive methods, showcasing nature’s wonders.

What Is The Lifespan Of Boa Snakes In The Wild?

In the wild, boa snakes typically live around 20 to 30 years. Their lifespan can vary depending on factors such as habitat, food availability, and predation. Boas have the freedom to thrive in their diverse ecosystems.

Are Boa Snakes Endangered Or At Risk Of Extinction?

Some boa snake species are endangered due to habitat loss, poaching, and the pet trade. Conservation efforts are essential to prevent their extinction. Awareness and protection can help save these fascinating creatures from disappearing.

Can Boa Snakes Regurgitate Their Food?

Yes, boa snakes can regurgitate their food if stressed or disturbed. This process is essential for their survival. However, it should not be a common occurrence, as regurgitation can be harmful to their health.

Conclusion

Boas stand as reptiles in the serpent world. Their heat-sensing pits, muscular bodies, and specialized jaws demonstrate nature’s evolutionary masterwork. These constrictors thrive across diverse ecosystems from tropical rainforests to arid deserts, adapting their hunting strategies and physiology to local conditions.

The constriction method that Boas employed—cutting off blood flow rather than suffocation, as previously thought—highlights their efficient predation techniques. Their reproduction strategy of live birth (viviparity) rather than egg-laying sets them apart from many other snake families and represents an evolutionary adaptation to their environments.

Conservation challenges face many boa species today, with habitat destruction and the exotic pet trade threatening wild populations. Understanding these magnificent serpents helps build appreciation for their ecological role as mid-level predators maintaining ecosystem balance.

The world of boas continues to yield new discoveries as herpetologists study their behavior, physiology, and evolutionary relationships. These serpentine specialists are among nature’s most perfectly designed predators, worthy of both scientific study and conservation efforts.