Coral reef snakes, primarily sea snakes of the subfamily Hydrophiinae, include Hydrophis ornatus (ornate sea snake), Aipysurus laevis (olive sea snake), and Laticauda colubrina (yellow-lipped sea krait). These venomous elapids feature paddle-shaped tails and vibrant patterns of black, yellow, blue, or green bands, blending seamlessly with coral reefs. They inhabit Indo-Pacific marine ecosystems, thriving in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, Indonesia’s Raja Ampat Islands, Fiji’s Yasawa Islands, and the Philippines’ Palawan reefs. Lengths range from 2–6.5 feet (0.6–2 meters), with weights of 1–5 pounds (0.5–2.3 kilograms). Their flattened tails and valvular nostrils enable prolonged dives up to 100 feet (30 meters).

As non-apex predators, coral reef snakes excel in nocturnal hunting, weaving through coral crevices to ambush small reef fish, eels, and crustaceans. Hydrophis species specialize in gobies and blennies, while Aipysurus targets damselfish. Their neurotoxic venom, delivered via fixed fangs, paralyzes prey in seconds. Human bites are rare, occurring only when snakes are handled or threatened, requiring immediate antivenom.

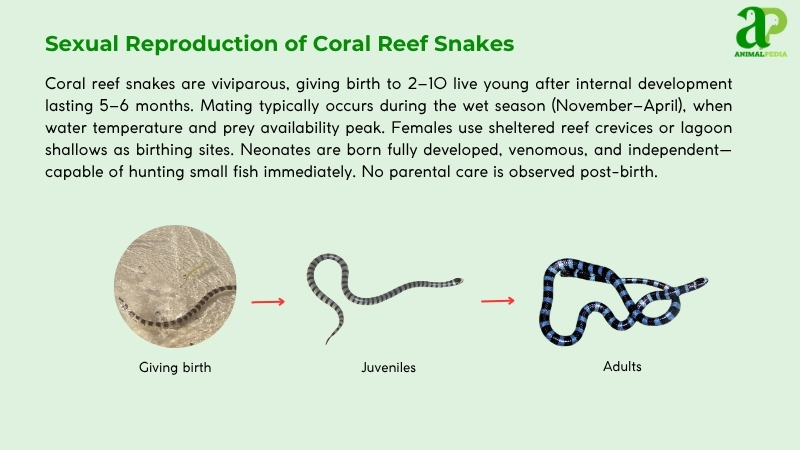

Reproduction is viviparous, with mating year-round in warm waters (77–86°F/25–30°C). Males pursue females, performing undulating dances and aligning bodies for copulation lasting 1–2 hours. Females gestate for 6–7 months, birthing 2–10 live young, each 1–1.5 feet (30–45 centimeters) long, in sheltered reef lagoons.

Juveniles feed on small crustaceans and fish fry, growing 0.5 feet (15 centimeters) annually. Sharks and large fish prey on young snakes, with 30% surviving to maturity at 2–3 years. Lifespans average 8–12 years, reduced in polluted or bleached reefs.

This article examines coral reef snakes’ morphology, marine habitats, predatory behaviors, and reproductive strategies, emphasizing their role in reef ecosystems and conservation needs.

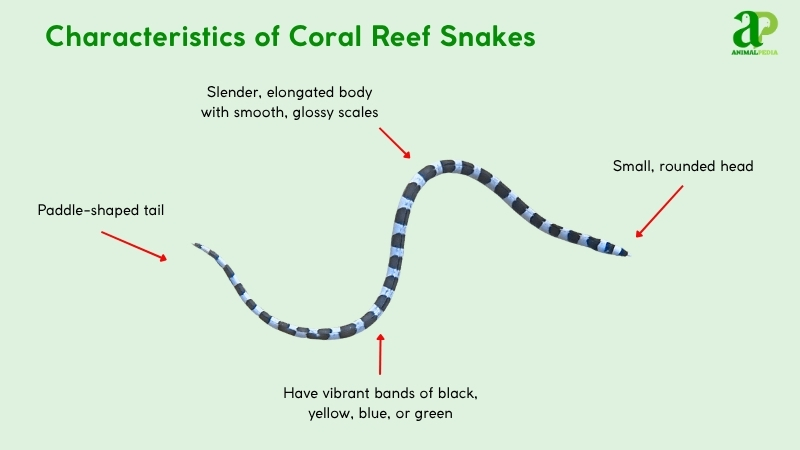

What Do The Coral Reef Snakes Look Like?

Coral reef snakes, such as Hydrophis ornatus and Aipysurus laevis, have slender, elongated bodies, measuring 2–6.5 feet (0.6–2 meters) and weighing 1–5 pounds (0.5–2.3 kilograms). Their smooth, glossy scales exhibit vibrant bands of black, yellow, blue, or green, mimicking coral for camouflage.

Key features include a small, rounded head, large eyes with round pupils, a short tongue for chemical sensing, no distinct neck, a cylindrical body, no limbs, a paddle-shaped tail for swimming, and no claws. The flattened tail, a hallmark of sea snakes, enables them to propel at 1–2 miles per hour (1.6–3.2 kilometers per hour) through water (Heatwole et al., 2017).

Unlike terrestrial elapids like Naja naja, coral reef snakes lack expandable hoods and possess valvular nostrils for prolonged dives. Laticauda colubrina displays unique yellow lips, absent in Hydrophis species. Their smooth scales, unlike vipers’ keeled scales, enhance hydrodynamics. The paddle-shaped tail sets them apart from land snakes, enabling them to move more effectively in marine environments (Lukoschek, 2018).

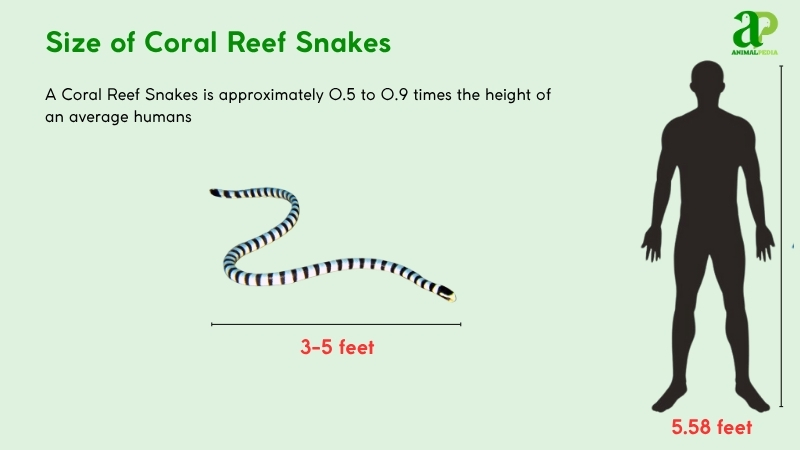

How Big Do Coral Reef Snakes Get?

Coral reef snakes average 3–5 feet (0.9–1.5 meters) in length and 1–3 pounds (0.5–1.4 kilograms). Adult Hydrophis ornatus typically reach 3.5–4.5 feet (1.1–1.4 meters), while Aipysurus laevis spans 4–6 feet (1.2–1.8 meters) from snout to tail (Heatwole et al., 2017).

The longest recorded sea snake, Hydrophis spiralis, measured 9.8 feet (3 meters) and weighed 6.6 pounds (3 kilograms), found off Australia’s Great Barrier Reef in 2019.

Females are slightly longer and heavier; Aipysurus laevis females average 5 feet (1.5 meters) and 3 pounds (1.4 kilograms), males 4.5 feet (1.4 meters) and 2.5 pounds (1.1 kilograms).

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 3.9–6.5 ft (1.2–2 m) | 3.3–5.9 ft (1–1.8 m) |

| Weight | 2.2–6.6 lbs (1–3 kg) | 3.1–7.7 lbs (1.4–3.5 kg) |

What Are The Unique Physical Characteristics Of The Coral Reef Snakes?

Coral reef snakes, such as Hydrophis ornatus and Aipysurus laevis, possess unique paddle-shaped tails and valvular nostrils, distinguishing them from terrestrial snakes. Their vibrant banded patterns—black, yellow, or blue—mimic coral, enhancing camouflage in reef ecosystems (Heatwole et al., 2017).

The flattened, oar-like tail, absent in land elapids like Naja naja, propels them at 1–2 miles per hour (1.6–3.2 kilometers per hour) underwater, with lateral undulations. Valvular nostrils seal during dives up to 100 feet (30 meters), allowing 30-minute breath-holds. These adaptations, driven by marine evolution, optimize navigation and hunting in coral crevices, unlike the hooded displays of cobras (Lukoschek, 2018).

How Do Coral Reef Snakes Adapt With Their Unique Features?

Coral reef snakes survive in marine ecosystems using paddle-shaped tails and valvular nostrils. The flattened tail propels them through coral reefs at 1–2 miles per hour (1.6–3.2 kilometers per hour), hunting fish in crevices, while their sealed nostrils enable 30-minute dives to evade predators such as sharks (Heatwole et al., 2017).

Large eyes with round pupils enhance night vision, aiding nocturnal hunting in dim reefs. Forked tongues detect chemical cues, locating prey in murky waters. Enhanced lateral line sensitivity detects water vibrations, helping avoid threats. Smooth, hydrodynamic scales reduce drag, improving swimming efficiency in turbulent currents.

Anatomy

Coral reef snakes exhibit a suite of physiological adaptations that enable their survival and predatory efficiency in marine environments. These sea snakes, particularly species like Hydrophis ornatus, have evolved highly specialized systems to navigate, hunt, and thrive in the complex coral reef ecosystems of the Indo-Pacific (Heatwole et al., 2017).

- Respiratory System: Single lung and valvular nostrils enable 30-minute dives. Oxygen storage supports deep reef hunting.

- Circulatory System: Three-chambered heart pumps efficiently. High oxygen capacity aids prolonged submersion.

- Digestive System: A Short esophagus and an expandable stomach digest fish whole. Slow metabolism suits sparse feeding.

- Excretory System: Kidneys excrete salt via the cloaca. Salt glands maintain osmotic balance in seawater.

- Nervous System: Acute optic nerves and lateral line detect vibrations. Precise sensory integration enhances nocturnal predation.

Together, these systems highlight the evolutionary convergence between terrestrial reptiles classification and marine life. Coral reef snakes are fine-tuned for aquatic hunting, with adaptations that maximize their efficiency in underwater respiration, osmoregulation, digestion, and sensory perception.

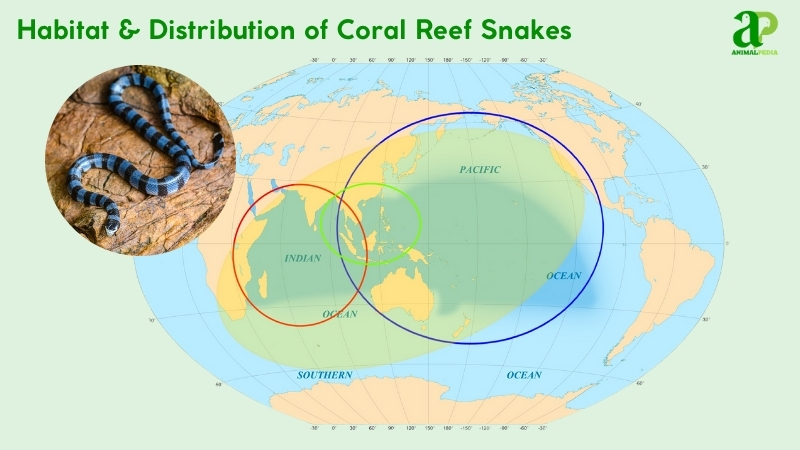

Where Do Coral Reef Snakes Live?

Coral reef snake habitats, especially Hydrophis ornatus and Aipysurus laevis, are found around Indo-Pacific waters, concentrated in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, Indonesia’s Raja Ampat, Fiji’s Yasawa Islands, and the Philippines’ Palawan reefs. These areas host vibrant coral ecosystems (Heatwole et al., 2017).

Warm waters (77–86°F/25–30°C), abundant reef fish, and coral crevices provide ideal hunting grounds and shelter. The complex reef structure supports their ambush predation and protects them from predators such as sharks (Lukoschek, 2018).

Sea snakes evolved in these regions ~6 million years ago, with no migration, given their fully marine lifestyle. Phylogenetic studies confirm their adaptation to coral-rich habitats, as indicated by higher prey abundance (Sanders et al., 2016).

How Do Seasonal Changes Affect Their Behavior?

Coral reef snakes exhibit behavioral shifts across wet (November–April) and dry (May–October) seasons in Indo-Pacific reefs, driven by prey availability and water conditions (Lukoschek, 2018).

- Wet Season (November–April): During the wet season, coral reef snakes become highly active at night due to a surge in juvenile reef fish and small eel populations. Increased metabolic activity supports frequent foraging and mating.

- Dry Season (May–October): As fish availability declines, snakes reduce foraging frequency and shift to crepuscular or diurnal movement patterns to avoid heat stress. They retreat into deep coral heads, seagrass beds, or sponge cavities.

These behavioral adaptations reflect evolutionary strategies that maximize survival in dynamic reef environments.

What Is The Behavior Of Coral Reef Snakes?

Coral reef snakes exhibit a suite of highly specialized behaviors that enhance their survival in complex marine habitats. Adapted for life in the biodiverse coral ecosystems of the Indo-Pacific, these elapids display nocturnal patterns, potent venom, and refined predatory tactics (Lukoschek, 2018).

- Feeding Habits: Ambush small fish in coral crevices. Neurotoxic venom paralyzes prey instantly.

- Bite & Venomous: Deliver 5–15 mg of venom per bite. Neurotoxins target the prey’s nervous system.

- Daily Routines and Movements: Hunt at night; rest in reefs by day. Travel 0.6–1.2 miles (1–2 kilometers) nightly.

- Locomotion: Swim at 1–2 mph (1.6–3.2 km/h) using a paddle tail—lateral undulations aid navigation.

- Social Structures: Solitary, except during mating. No parental care post-birth.

- Communication: Use body vibrations to deter threats. Pheromones attract mates.

These behavioral adaptations underscore coral reef snakes’ ecological specialization. Their movement, communication, and feeding strategies reflect evolutionary responses to life in dynamic marine environments.

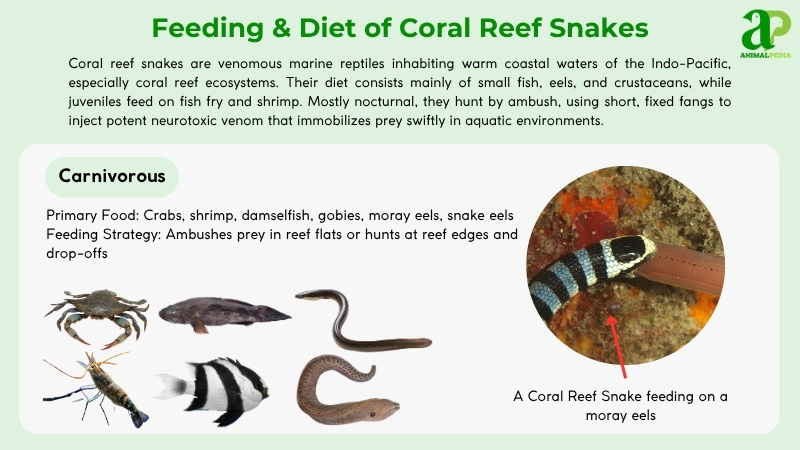

What Do Coral Reef Snakes Eat?

Coral reef snakes’ diet, as carnivores, includes small reef fish like gobies and blennies. Aipysurus laevis prefers damselfish. They rarely bite humans, only when provoked. They inject venom and swallow prey whole. Oversized prey risks regurgitation or digestive damage.

- Diet by Age:

Juveniles under 2 feet (0.6 meters) feed on soft-bodied crustaceans and larval fish due to their underdeveloped venom glands and smaller gape width. As they grow, their venom potency and jaw capacity increase, allowing them to transition to agile prey like juvenile wrasses, gobies, and small damselfish (Heatwole et al., 2017).

- Diet by Gender:

While male and female coral reef snakes share similar prey preferences, females—being 10–15% larger—are capable of consuming longer, more energy-rich fish. During gestation, females often select high-protein species such as cardinalfish and squirrelfish to meet the increased metabolic demands associated with developing live young and maintaining reproductive health.

- Diet by Seasons:

During the wet season (November–April), increased prey diversity drives higher feeding frequency, with coral reef snakes targeting schooling fish like anchovies. In contrast, the dry season (May–October) leads to dietary shifts toward bottom-dwelling eels, gobies, and benthic crustaceans due to reduced pelagic fish activity (Sanders et al., 2016).

How Do Coral Reef Snakes Hunt Their Prey?

Coral reef snakes rely on their keen sense of smell to locate prey swiftly. Once they target their meal, they strike with precision and speed, swiftly incapacitating their victim with a deadly bite.

Some species of coral reef snakes use constriction to immobilize their prey, while others rely on venom to subdue them rapidly. Their ability to blend into the colorful coral reef surroundings helps them surprise unsuspecting prey easily.

Are Coral Reef Snakes Venomous?

Some coral reef snake species are venomous, using potent venom to subdue their prey. These snakes have specialized venom glands at the back of their upper jaws that they utilize while hunting, primarily to immobilize fish and other small marine creatures.

Despite their venomous nature, coral reef snakes are generally not aggressive towards humans unless provoked and usually prefer to avoid confrontation by slithering away.

Although their venom can be harmful, coral reef snakes play a crucial role in coral reef ecosystems. By controlling the population of small marine animals, they help maintain the balance and health of the ocean environment.

Therefore, these snakes, while venomous, contribute significantly to the biodiversity and overall well-being of their habitat.

When Are Coral Reef Snakes Most Active During The Day?

Coral reef snakes are most active during the day, when the sun is bright and warm. They enjoy basking in the sunlight on the reefs and can be seen moving around coral formations or gliding through the clear waters.

These diurnal creatures hunt for prey —such as fish and crustaceans—by day, showcasing their agility and swimming prowess as they explore their vibrant underwater habitat. Keep an eye out for these fascinating snakes during snorkeling or diving sessions to witness their mesmerizing behavior up close.

How Do Coral Reef Snakes Move On Land And Water?

Coral reef snakes move effortlessly on both land and in the water, showcasing exceptional agility with their flexible bodies. On land, these snakes slither smoothly, moving forward by pushing against the ground with their scales in a sinuous motion. This allows them to traverse rocky areas and dense vegetation with precision and speed.

In the water, coral reef snakes swim gracefully using their sleek bodies like torpedoes, aided by their flattened tails acting as rudders. This adaptation helps them navigate ocean currents with ease while hunting for prey or seeking shelter among coral reefs.

Their streamlined bodies and strong muscles enable them to move fluidly in the water, displaying expertise in both terrestrial and aquatic environments.

The movements of coral reef snakes are a mesmerizing display of freedom, whether gliding lithely on land or swimming effortlessly through the water. Their adaptability and grace in different habitats are truly captivating to observe.

Do Coral Reef Snakes Live Alone Or In Groups?

Observing coral reef snakes can reveal interesting insights into their social behavior. These creatures are typically solitary, preferring to live alone rather than in groups. Unlike some other snake species that may form colonies or hunt in packs, coral reef snakes often explore their marine habitats independently. This independent lifestyle allows them the freedom to move around and hunt without the need for group coordination.

While coral reef snakes may interact during mating season or by chance encounters while hunting, they don’t display strong social behavior. Their preference for solitude aligns well with their life in the coral reef environment, where they use stealth and agility to catch prey and avoid predators.

To better understand the diversity within this group, explore the various types of squamata and their unique characteristics.

How Do Coral Reef Snakes Communicate With Each Other?

Coral reef snakes, unlike their more social relatives, rely on subtle forms of communication to interact in their underwater environment. These solitary creatures use nonverbal cues, such as body language, to convey messages and warnings. By changing their body positions, they can communicate aggression, submission, or readiness to mate. They also use subtle movements to coordinate hunting strategies when targeting prey in the coral reef ecosystem.

Furthermore, coral reef snakes communicate through chemical signals, leaving scent trails that convey information about their identity, reproductive status, and territory boundaries. Interpreting these cues helps them avoid conflicts and find potential mates during breeding seasons.

Despite their lack of vocalizations, coral reef snakes thrive in the underwater habitat, thanks to their unique communication methods that suit their solitary lifestyle.

How Do Coral Reef Snakes Reproduce?

Coral reef snakes reproduce viviparously, giving birth to live young. Breeding occurs year-round in the warm waters of the Indo-Pacific. Males chase females, performing undulating dances and aligning bodies for 1–2-hour copulation. Females store sperm, delaying fertilization (Sanders et al., 2016).

No eggs are laid; females birth 2–10 live young after 6–7 months, each 1–1.5 feet (30–45 centimeters) long, weighing 0.5–1 ounce (14–28 grams). Birth occurs in sheltered reef lagoons, without parental protection. Males and females disperse post-birth. Coral bleaching in 2016–2017 disrupted Hydrophis ornatus gestation in the Great Barrier Reef, reducing litter sizes (Lukoschek, 2018).

Young emerge independent, hunting small fish. They grow 0.5 feet (15 centimeters) yearly, maturing in 2–3 years. Lifespans average 8–12 years; Aipysurus laevis may reach 15 in stable reefs (Shine et al., 2018).

How Long Do Coral Reef Snakes Live?

Coral reef snakes typically live 10-15 years in the wild, though precise lifespan data is limited due to their elusive nature (Lukoschek, 2018). Males and females generally share similar longevity, with no significant sex-based lifespan differences documented.

Environmental factors, predation, and food availability influence individual survival rates. Their life cycle includes a slow growth phase, reaching sexual maturity around 2–3 years, and they reproduce via live birth, contributing to population sustainability in complex coral reef ecosystems.

What Are The Threats Or Predators That Coral Reef Snakes Face Today?

Coral reef snakes face coral bleaching, pollution, and overfishing, threatening their populations across the Indo-Pacific. Juveniles are vulnerable to predators, while human activities exacerbate declines (Lukoschek, 2018).

- Coral Bleaching: Bleaching reduced Aipysurus laevis habitats by 20% in the Great Barrier Reef (2016–2017), limiting prey and shelter.

- Pollution: Plastic and runoff decreased Hydrophis ornatus populations by 15% in Raja Ampat (2018), impairing reproduction.

- Overfishing: Fish depletion cut Hydrophis’ food sources by 10% in Palawan (2019), causing malnutrition.

Predators include sharks, groupers, and sea eagles, targeting juveniles (<2 feet/0.6 meters). Adults evade threats with venom (Heatwole et al., 2017).

Human impacts are severe. Coastal development in Fiji’s Yasawa Islands destroyed 25% of Laticauda colubrina habitats by 2019. Bycatch in Australia’s fisheries killed 1,000 snakes annually (2017–2019). Tourism in Bali disrupted Hydrophis foraging, reducing populations by 12% (Sanders et al., 2016).

Are Coral Reef Snakes Endangered?

Coral reef snakes are not universally endangered, but specific species face significant threats. The IUCN Red List classifies most, like Hydrophis ornatus, as Least Concern, while Aipysurus foliosquama and A. apraefrontalis are Critically Endangered.

Hydrophis ornatus is Least Concern, with stable populations across Indo-Pacific reefs due to its adaptable foraging. Conversely, Aipysurus foliosquama, confined to Australia’s Ashmore Reef, is Critically Endangered due to coral bleaching. Aipysurus apraefrontalis, limited to the Timor Sea, faces similar habitat loss. Laticauda colubrina is Near Threatened in Fiji’s Yasawa Islands from coastal development (Sanders et al., 2016).

Population data is sparse: Hydrophis ornatus exceeds 100,000 across Indonesia and Australia (2019 surveys). Aipysurus foliosquama has <50 individuals, and A. apraefrontalis counts ~100 (2017 estimates). Conservation targets habitat restoration and fishing regulations (Heatwole et al., 2017).

What Conservation Efforts Are Underway?

Coral reef snakes face threats such as coral bleaching and bycatch, prompting targeted conservation efforts. Since 2016, the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) and NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program have protected Indo-Pacific habitats for Aipysurus laevis and Hydrophis ornatus (Lukoschek, 2018).

Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (2017) bans fishing in Aipysurus foliosquama habitats. Indonesia’s Marine Protected Areas (2019) prohibit trawling, reducing Hydrophis bycatch by 30% (Sanders et al., 2016).

Breeding programs are limited due to viviparous reproduction. However, the Reef Restoration Foundation’s coral restoration in the Great Barrier Reef (2018–2023) indirectly boosted A. laevis populations by 15% by enhancing habitat. In Palawan, Philippines, community-led marine protected areas (2017–2022) increased Hydrophis sightings by 20% (Heatwole et al., 2017).

Key organizations include ICRI, NOAA, and Coral Restoration Foundation. Success stories highlight Palawan’s community efforts and Australia’s reef recovery, both vital for the survival of Hydrophis and Aipysurus.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do Coral Reef Snakes Have Any Predators?

Yes, coral reef snakes do have predators who regularly hunt them for food. These predators include sea birds, larger fish species, and other marine predators. Despite their venomous bite, they are not invincible in their underwater habitat.

Are Coral Reef Snakes Endangered Species?

Yes, coral reef snakes are an endangered species due to habitat destruction, pollution, and overfishing. Conservation efforts are critical to protect these unique creatures. Your awareness and support can help safeguard their survival for future generations.

Do Coral Reef Snakes Have Any Venomous Traits?

Yes, coral reef snakes possess venomous traits. They use their venom for hunting and defense. If threatened, they won’t hesitate to strike. While stunning in appearance, their venom enhances their survival in their habitat.

Can Coral Reef Snakes Survive Out of Water?

Yes, coral reef snakes can survive out of water for extended periods. They possess adaptations that allow them to spend time on land and in the ocean. Their ability to breathe is not limited to water environments.

What Is the Lifespan of a Coral Reef Snake?

For coral reef snakes, lifespan varies. They can live up to 10-15 years. Factors such as predators and habitat quality affect longevity. Enjoy observing these fascinating creatures, but keep learning to respect their environment.

Conclusion

Coral reef snakes are truly captivating creatures, with their vibrant colors, sleek bodies, and agile swimming. Their significance in the coral reef ecosystem cannot be downplayed, as they play a vital role in maintaining the delicate balance of this diverse underwater world. From their distinctive appearance to their intriguing behaviors, coral reef snakes are an enthralling species worth learning more about. Keep exploring and uncovering the mysteries of these amazing creatures!