Coral snakes (Micrurus spp.) are venomous, slender serpents of the Elapidae family, known for their striking red, yellow, and black bands. It’s important to note that these are terrestrial (land-dwelling) snakes, and are a completely different group from the similarly-named, but fully-aquatic, Coral Reef Snake. Over 100 species of true coral snake exist, divided between Old World (27 species) and New World (83 species) groups. These elapids possess potent neurotoxic venom that affects nerve function.

Key species include Micrurus fulvius (Eastern Coral Snake) in the southeastern U.S., and Micrurus nigrocinctus (Central American Coral Snake) from Mexico to Colombia. Micruroides euryxanthus (Sonoran Coral Snake) inhabits the southwestern U.S., while Calliophis bivirgatus (Blue Malaysian Coral Snake) lives in Southeast Asia.

Most coral snakes measure 60-90 cm (2-3 ft), though M. fulvius can reach 120 cm. Their range extends from North Carolina to Argentina, including island populations like Roatán, Honduras.

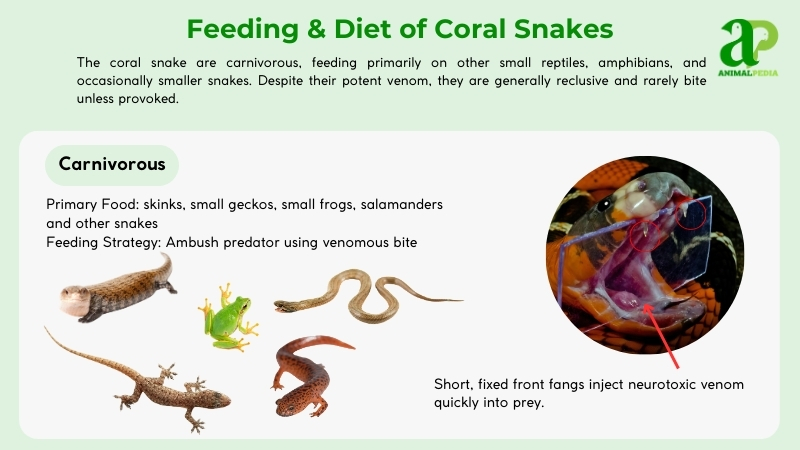

As fossorial apex predators, coral snakes hunt smaller snakes, lizards, and amphibians. They use a distinctive chew-to-envenomate technique due to their short, fixed fangs. Human envenomations are rare, occurring mainly during handling attempts, as these serpents typically avoid confrontation.

Reproduction involves spring mating, with females laying 3-13 eggs after vitellogenesis. Eggs incubate for about 60 days, producing 18-23 cm venomous hatchlings. Sexual maturity takes several years, with captive specimens living about 7 years, though wild longevity data remains limited.

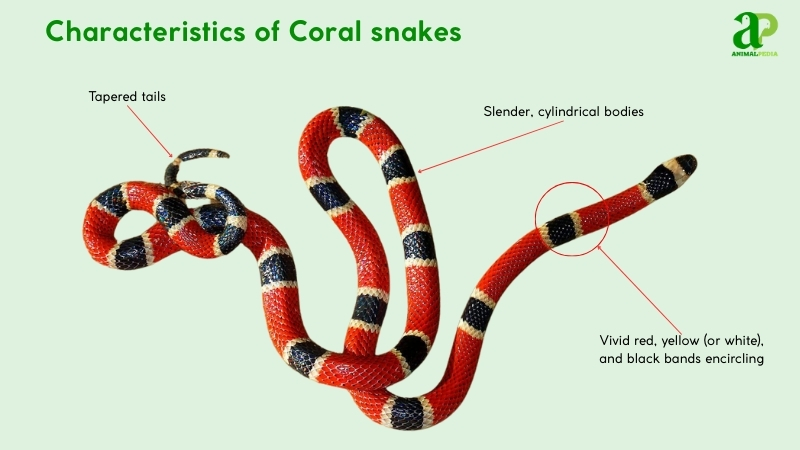

What Do Coral Snakes Look Like?

Coral snakes (Micrurus and related genera) have slender, cylindrical bodies with tapered tails. Their distinct pattern—alternating red, yellow/white, and black bands—fully encircles the body. Their smooth, glossy scales feel sleek, helping them glide through forest debris. Unlike many serpents, their pattern remains consistent from head to tail.

Their heads are small, blunt, and barely distinct from their necks. A black-tipped snout precedes their banded pattern. Small, round eyes with dark irises blend with head coloration, serving their burrowing lifestyle. Their forked tongue—red or black—flicks to detect chemicals. The neck transitions smoothly into the banded body, which lacks limbs, a feature typical of all snakes. The short, pointed tail continues the body pattern.

Coral snakes differ from mimics like scarlet kingsnakes (Lampropeltis elapsoides) by their band sequence—”red touches yellow” in Micrurus fulvius versus “red touches black” in mimics. Their smooth scales contrast with the rough, keeled scales of some colubrids. Their head shape appears less triangular than that of pit vipers and lacks facial heat-sensing pits. These features—band pattern, scale texture, and head shape—identify coral snakes as true elapids, though novices often misidentify them due to effective mimicry.

Explore other snakes

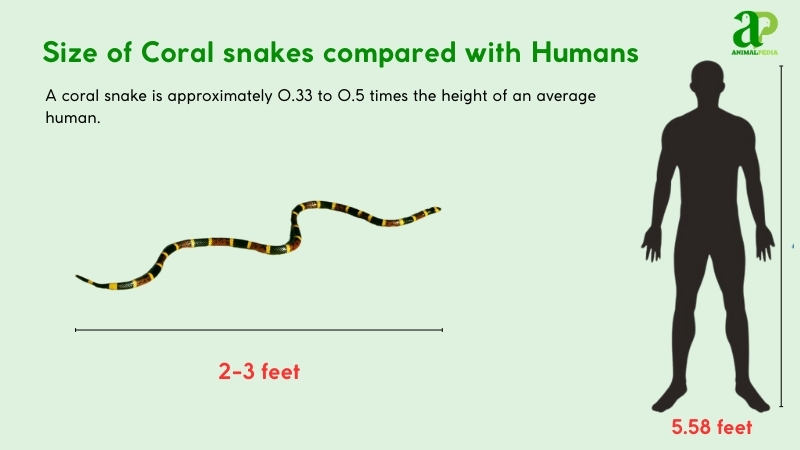

How big do coral snakes get?

Coral snakes average 2-3 ft in length and 1-2 lbs in weight, with species like Micrurus fulvius showing slight variation. The longest and heaviest recorded, a Micrurus fulvius, reached 4.25 ft and 3.3 lbs, found in Florida.

Adults typically measure 2-3.3 ft snout-to-tail, with M. nigrocinctus sometimes exceeding this. Males average 2.6 ft and 1.3 lbs, while females, at 2.5 ft and 1.8 lbs, are shorter but heavier due to reproductive demands. This dimorphism is minor, mainly in body mass. See the table below:

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 2.6 ft | 2.5 ft |

| Weight | 1.3 lbs | 1.8 lbs |

What are the unique physical characteristics of the Species?

Coral snakes have a distinct venom system with short, fixed fangs (0.14 inches) at the front of their maxilla. This feature appears only in elapids among New World serpents.

Unlike pit vipers with retractable fangs or colubrids with rear fangs, coral snakes’ fixed-fang structure, combined with their distinctive red-yellow-black banding pattern (as in Micrurus surinamensis), sets them apart from mimics like scarlet kingsnakes, which display different band arrangements. This morphology supports their specialized neurotoxic hunting strategy.

The 2023 research “Toxic and antigenic characterization of Peruvian Micrurus surinamensis coral snake venom” reveals their venom contains primarily phospholipases A2 and three-finger toxins. Their envenomation requires a chewing motion because their fixed fangs have limited reach. This differs from the strike-and-release technique of pit vipers.

A 2024 study, “In vivo neutralization of coral snake venoms with an oligoclonal nanobody mixture,” confirms that this venom-delivery system evolved specifically for the capture of reptilian prey. Proteomic analysis highlights its elapid lineage. These anatomical adaptations define coral snakes’ ecological position as specialized predators.

How do coral snakes sense their environment with its unique features?

Coral snakes survive using fixed fangs and potent neurotoxic venom to capture small reptiles and amphibians. This suits their burrowing, ambush lifestyle perfectly. Their venom delivery compensates for small body size (2-3 ft), allowing effective predation in confined spaces where larger fangs would be ineffective.

Their sensory adaptations are specialized for underground detection. Chemosensory forked tongues collect and analyze scent particles, guiding them to prey through soil and leaf litter. Small eyes function well in low light, helping them navigate dim burrows. Their vibration-sensitive dermis detects subtle ground movements, alerting them to approaching prey or threats. Basic auditory perception through jawbone conduction captures low-frequency vibrations, enhancing environmental awareness.

These integrated sensory systems create an effective multimodal perception network that optimizes their stealthy, venom-dependent hunting strategy in subterranean habitats. This sensory suite compensates for limited vision in their primary ecological niche.

Anatomy

Coral snake physiology supports their venomous, burrowing lifestyle through efficient anatomical systems:

- Respiratory System: Coral snakes breathe through a single functional right lung, which is elongated to fit their slender bodies. Specialized tracheal air sacs ensure efficient oxygen exchange during underground movement.

- Circulatory System: Their three-chambered heart (two atria, one ventricle) powers blood circulation. Hemotoxic venom components travel quickly through a robust vascular network to immobilize prey.

- Digestive System: A streamlined tract with a muscular esophagus digests whole prey. Potent enzymes break down food slowly, supporting the infrequent feeding pattern typical of these ambush hunters.

- Excretory System: Dual kidneys filter waste products into uric acid, which is expelled via the cloaca. This water-conservation mechanism is essential for survival in arid habitats.

- Nervous System: A sophisticated brain and spinal cord coordinate precise movements and venom delivery. The Jacobson’s organ enhances chemosensory abilities, allowing prey detection in the dark.

These physiological adaptations make coral snakes remarkably effective predators despite their small size and secretive nature.

How Many Types Of Coral Snakes?

Coral snakes, vibrant venomous serpents, comprise about 80 species within the family Elapidae. These span genera like Micrurus (New World) and Sinomicrurus (Asia), with Micrurus fulvius (Eastern coral snake) among the most recognized. Their distinct red, yellow, and black bands signal danger across the Americas and parts of Asia.

Classification is based on morphological and genetic traits, formalized by the 19th-century herpetologist Edward Drinker Cope, and refined by modern phylogenetics. Recent studies (Slowinski et al., 2016) use DNA sequencing to clarify relationships, distinguishing coral snakes from cobras and kraits within Elapidae.

The branch diagram splits Elapidae into two subfamilies: Hydrophiinae (sea snakes) and Elapinae, which includes coral snakes. Genera Micrurus (65 species), Micruroides (2 species), and Calliophis (10 species in Asia) form key clades.

├──Elapidae

├── Hydrophiinae (Sea Snakes)

└── Elapinae

├── Micrurus (65 species)

├── Micruroides (2 species)

├── Sinomicrurus (5 species)

└── Calliophis (10 species)

Special cases include Micruroides euryxanthus (Sonoran coral snake), with atypical band patterns, and Leptomicrurus, adapted to Andean highlands. These exceptions highlight evolutionary diversity within the order Squamata.

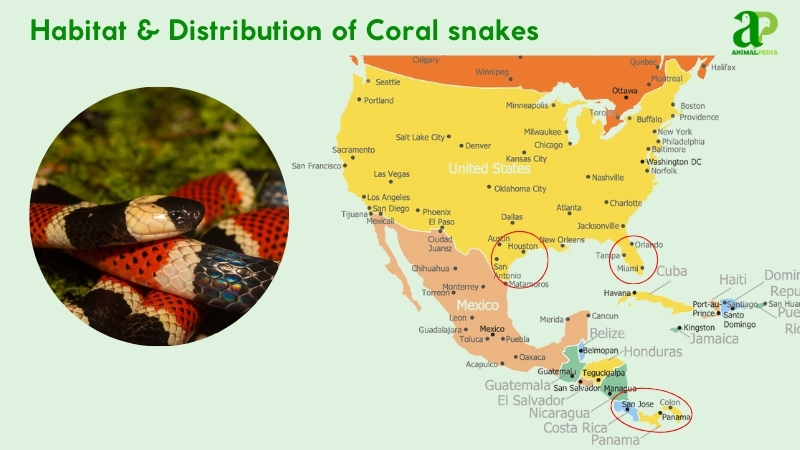

Where Do Coral Snakes Live?

Coral snakes inhabit the Americas. They thrive in the southeastern United States (Florida, eastern Texas), Central America (Costa Rica, Panama), and South America (Amazon Basin, northern Argentina).

These venomous elapids prefer warm, humid environments. You’ll find them in tropical rainforests, pine flatwoods, and scrublands. These habitats provide loose soil and leaf litter that support their burrowing lifestyle and access to prey—small reptiles and amphibians. Their distinctive aposematic coloration works effectively in these environments, warning potential predators.

Coral snakes have occupied these ecological niches for millions of years, with minimal migration. Their geographic distribution remains stable due to consistent climate conditions, though some exhibit seasonal movements.

Recent phylogenetic research by Reyes-Velasco and colleagues (2023) on Micrurus nigrocinctus demonstrates their specialized adaptation to neotropical ecosystems. This adaptation stems from prey specialization and genetic divergence, confirming their established presence in these regions over evolutionary timescales.

How do seasonal changes affect their behavior?

Coral snakes change their behavior with the seasons due to shifts in temperature and humidity. During warm months, these elapids become highly active as heat increases their metabolism. This energy surge drives them to hunt prey like smaller snakes, lizards, frogs, and rodents.

When winter arrives, coral snakes retreat underground. They enter brumation—a reptilian dormancy state similar to hibernation—conserving energy as temperatures drop. These ophidians burrow deeper into the substrate to maintain adequate body temperature.

Humidity fluctuations also dictate their habitat selection and activity patterns. During dry periods, they seek moisture-retaining microhabitats, while rainy seasons may increase their surface activity. These seasonal adaptations demonstrate the remarkable thermoregulatory capabilities of Micruroides and Micrurus species throughout their geographic range in the Americas.

What Is The Behavior Of Coral Snakes?

The Coral Snake has distinct traits and behaviors as follows:

- Diet: Strictly carnivorous, feeding on small snakes, lizards, and amphibians. Juveniles eat smaller prey, while adults consume larger reptiles. Diet remains consistent across age, gender, and seasons.

- Hunting Mechanisms: Ambush predators use fixed, grooved fangs to inject slow-acting venom. They hold and chew prey to ensure venom delivery, favoring elongate species such as skinks and blind snakes.

- Daily Activity Patterns: Active mainly in the early morning and late afternoon, especially during rainy or breeding seasons. Typically hidden underground or in leaf litter.

- Locomotion Capabilities: Slithers smoothly across land; aquatic species use flattened tails to swim efficiently in slow water.

- Social Structure: Solitary by nature, emerging mainly for mating or after rain. No group living observed.

- Communication: Uses body movements and visual signals. Mating or territorial interactions involve intertwining displays. Bright colors serve as a visual warning.

Coral snakes’ venom, stealth, and solitary habits reflect their adaptability and success in varied habitats.

What do coral snakes eat?

Coral snakes are strictly carnivorous, preying on small reptiles (e.g., lizards and blind snakes) and amphibians, with a preference for elongated species such as skinks. Their neurotoxic venom subdues prey, and they rarely target humans due to their small mouths and secretive nature.

- Diet by Age: Juveniles (0–1 year) eat smaller prey, such as tiny lizards or froglets, to match their size. Subadults (1–3 years) and adults (3+ years) consume similar prey, including larger snakes or amphibians, with no major dietary shift as their hunting efficiency improves.

- Diet by Gender: Males and females have identical diets, both using venom to immobilize prey, showing no dietary or hunting differences.

- Diet by Seasons: Coral snakes maintain a consistent diet year-round, but in drier seasons (e.g., June–November in Central America), they may focus on amphibians near water sources due to reduced prey availability in their tropical habitats.

They bite to envenomate, then swallow prey whole, headfirst, without chewing. Oversized prey risks regurgitation or injury.

How do coral snakes hunt their prey?

Coral snakes hunt with stealth and precision. These secretive elapids target smaller reptiles, amphibians, nestling birds, and rodents. Their hunting arsenal includes a pair of fixed front fangs through which they deliver potent neurotoxic venom.

Unlike pit vipers such as the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake species, which strike and retreat, coral snakes maintain their bite grip. They use deliberate chewing motions to inject venom gradually into the prey’s tissues. This slow-acting venom paralyzes the prey’s respiratory system, reflecting their patient hunting strategy.

These fossorial predators spend most of their lives underground or beneath leaf litter. They emerge primarily during wet periods or breeding season. Despite their lethal capabilities, coral snakes rarely display aggression toward humans, accounting for less than 1% of venomous snakebites in North America.

The coral snake’s hunting behavior exemplifies evolutionary adaptation in the elapid family. Their specialized prey-restraint technique and targeted venom-delivery system make them efficient hunters in their ecological niche.

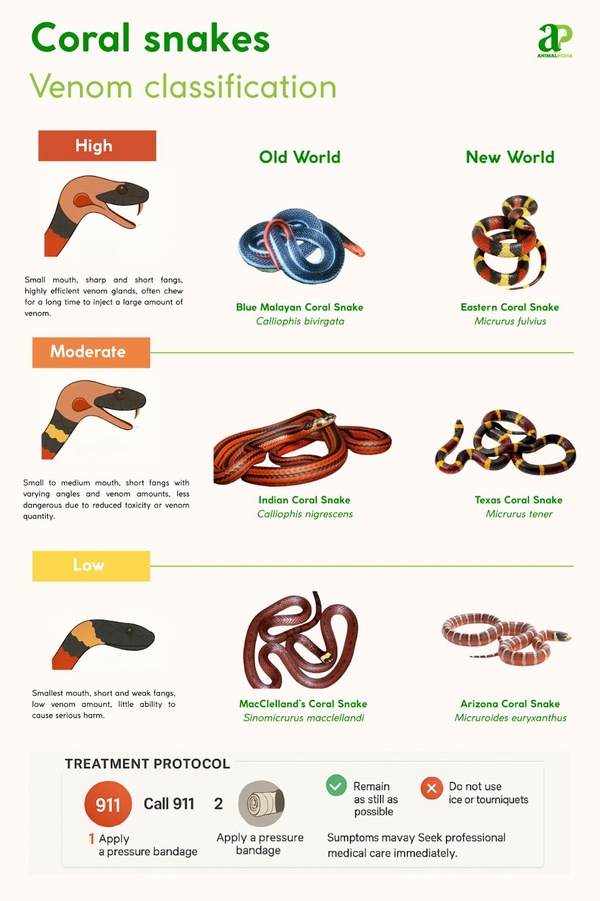

Are coral snakes venomous?

Coral snakes possess potent neurotoxic venom, which is crucial to their survival. These elapids have small, fixed hollow fangs in the front of their mouths that inject venom when they bite. Despite their toxic venom, coral snakes rarely attack humans and account for less than 1% of venomous snake bites in the United States.

Their venom composition serves dual purposes: self-defense and prey immobilization. Unlike pit vipers with hinged fangs, coral snakes have permanently erect fangs with specialized grooves for venom delivery. Though their fangs lack the penetration power of a Western Rattlesnake or cobras, these ophidians compensate through a distinctive bite mechanism—they grasp prey firmly and perform chewing motions to maximize envenomation.

The toxicity of coral snake venom varies across species in both the New World (Americas) and the Old World (Asia/Africa), with some species producing more potent neurotoxins than others.

When are coral snakes most active during the day?

Coral snakes become most active during the early morning and late afternoon hours. These venomous elapids remain elusive, burrowing underground or hiding within leaf litter on rainforest floors. They typically emerge only during rainy periods or breeding seasons.

Some species, like the Aquatic coral snake (Micrurus surinamensis), thrive in slow-moving waterways with dense vegetation, showing their habitat specialization.

Their diet consists primarily of smaller snakes, lizards, frogs, nestling birds, and small rodents. Despite possessing potent neurotoxic venom, coral snakes rarely show aggression toward humans. Their defensive behavior usually involves displaying their bright aposematic coloration to warn predators.

In the United States, coral snakes account for less than one percent of annual snake bites. Their venom-delivery mechanism differs from that of vipers; rather than striking quickly, they grasp and chew their prey, allowing more effective envenomation. This distinctive feeding behavior reflects their evolutionary adaptation as specialized predators.

How do coral snakes move on land and water?

Coral snakes move on land using lateral undulation, pressing their smooth scales against ground surfaces for propulsion. Their cylindrical bodies glide across grass, soil, and leaf litter with swift, precise movements. When threatened or hunting, they display remarkable agility and speed.

Some coral snake species show semi-aquatic adaptations. In water, these elapids use serpentine swimming motions, moving their bodies in S-shaped waves. Species like the aquatic coral snake (Micrurus surinamensis) possess slightly compressed tails that provide better propulsion in slow-moving streams and shallow ponds.

Their locomotion versatility enables coral snakes to thrive in diverse ecosystems from dry forests to wetland margins. This behavioral flexibility helps them hunt a variety of prey, including other snakes, lizards, and small mammals. The neurotoxic venom they deliver makes their efficient movement patterns especially dangerous to both potential predators and prey.

Do coral snakes live alone or in groups?

Coral snakes live alone. These reclusive reptiles prefer solitary existence rather than group living. They spend most of their lives underground or beneath rainforest leaf litter, emerging only during rainfall or mating seasons.

Some species, particularly aquatic coral snakes, inhabit water bodies with thick vegetation. Their diet consists primarily of smaller snakes, lizards, amphibians, and rodents. They use their small, fixed neurotoxic fangs to inject venom when hunting prey.

Despite being venomous elapids, coral snakes rarely show aggression toward humans. They account for less than one percent of snakebites in the United States. Their distinctive chewing mechanism during bites results from their anatomical fang structure.

In captivity, coral snakes typically survive about seven years. Their solitary behavior represents an evolutionary adaptation that helps them thrive in their natural ecological niches.

How do coral snakes communicate with each other?

Coral snakes, solitary reptiles by nature, communicate through specific methods despite their reclusive behavior. These venomous elapids use visual signals and substrate-borne vibrations as their primary means of communication.

When encountering another coral snake, they perform a stereotyped interaction ritual – intertwining their bodies in a precise pattern. This behavior serves multiple functions: establishing dominance hierarchies, signaling reproductive status, and defending territory. Their aposematic coloration (bright red, yellow, and black bands) communicates danger to predators while also playing a role in intraspecific recognition.

Though largely fossorial (burrowing), coral snakes maintain social connections through specialized communication methods. Their communication system remains effective despite limited social contact, demonstrating evolutionary adaptation to their secretive lifestyle. This chemical and visual language characterizes the behavioral ecology of these cryptic Micrurus species.

How Do Coral Snakes Reproduce?

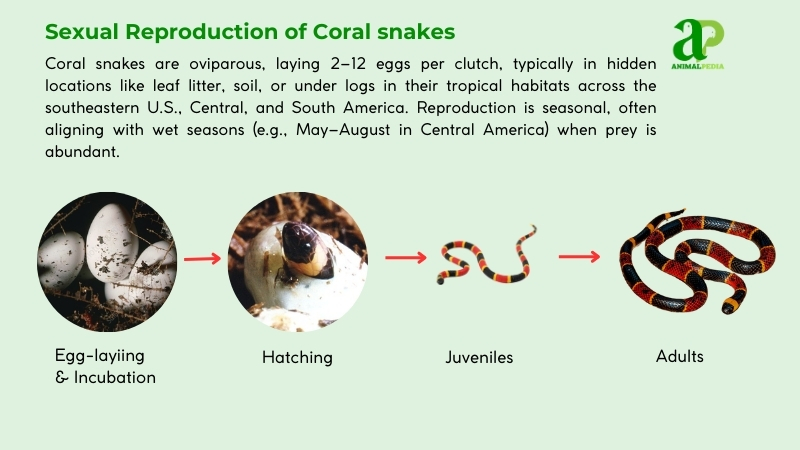

Coral snakes reproduce as oviparous reptiles, laying eggs instead of giving live birth. Males fertilize females internally using paired reproductive organs called hemipenes to transfer sperm.

The breeding cycle begins in spring (March-May) for North American species like Micrurus fulvius (Eastern coral snake). Males actively track females by following pheromone trails, while females remain relatively stationary. Courtship behavior involves the male coiling around the female and aligning reproductive openings for mating, which can last several hours. Male competition exists, but physical combat rarely occurs due to size differences.

After successful mating, females deposit 2-13 eggs (typically 5-7 for Eastern coral snakes) around June-July. Each clutch contains eggs weighing 2-3 grams, though research data remains limited. Females select microhabitats for egg deposition—underground burrows, decomposing vegetation, or rotting logs with suitable moisture levels. Unlike some reptiles, coral snakes construct no nest and provide no parental care. Males have no role in offspring development. Reproductive disruptions occur rarely, typically due to environmental stressors such as drought.

Incubation takes 60-90 days, with hatchlings emerging in late summer (August-September). Newborns measure approximately 20 cm and possess a specialized egg tooth to break their shell. They exhibit immediate independence, hunting small prey like tiny reptiles and arthropods without parental guidance.

How long do coral snakes live?

Coral snakes typically live five to seven years in captivity. Their lifespan in the wild varies based on habitat conditions, predation, and food availability. These venomous elapids reproduce through internal fertilization. Males possess paired reproductive organs called hemipenes. The breeding cycle occurs twice yearly—once in spring through early summer and again from late summer into early fall.

Male coral snakes rarely engage in combat for mating rights. This lack of competition likely stems from sexual dimorphism, in which males are smaller than females. Female coral snakes are oviparous, laying clutches of five to seven eggs between May and July. After approximately 60 days of incubation, hatchlings emerge fully developed with functional venom glands. Environmental factors such as temperature and rainfall significantly affect their reproductive success and overall longevity in natural habitats.

What Are The Threats Or Predators That Coral Snakes Face Today?

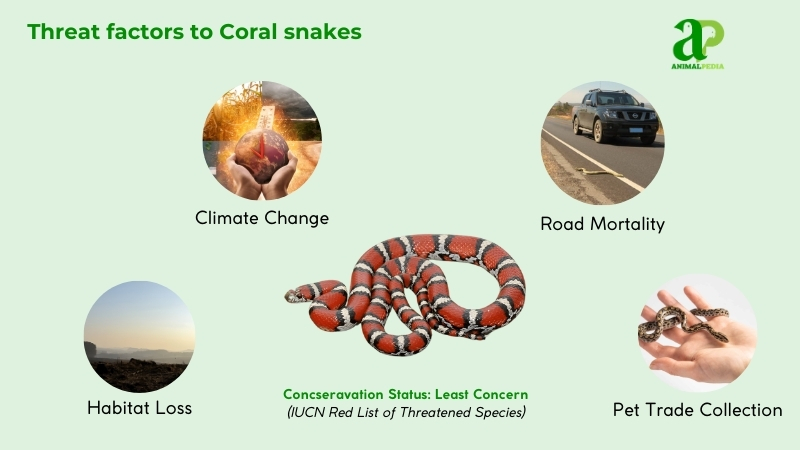

Coral snakes face four major threats today: habitat destruction, climate disruption, vehicle strikes, and illegal collection. Natural predators include raptors (hawks, eagles), ophiophagous snakes (kingsnakes, indigo snakes), and mesopredators (raccoons, opossums).

- Habitat fragmentation devastates coral snake populations. Urban expansion and forest clearing eliminate underground retreats and reduce prey abundance. Populations crash in developed areas where continuous forest cover vanishes.

- Climate change threatens coral snakes through thermal stress and shifts in precipitation. Rising temperatures alter hibernation patterns and disrupt breeding cycles. Weather extremes reduce reproductive output and survival rates.

- Road mortality hits coral snakes hard. Their slow movement makes them vulnerable to vehicles, especially during seasonal migrations. Fatalities peak in spring and fall when movement increases.

- The pet trade exploits these elapids for their vivid coloration. Poaching removes breeding adults from wild populations. Enforcement gaps allow continued collection despite legal protections in many jurisdictions.

Coral snakes are preyed upon by birds of prey (hawks, eagles), larger snakes (kingsnakes, indigo snakes), and mammals (raccoons, opossums), which exploit their habitats and challenge their survival.

Are coral snakes endangered?

Coral snake species vary in conservation status. The Eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius) remains not endangered, while the Roatan coral snake (Micrurus ruatanus) faces critical endangerment.

The IUCN Red List classifies most coral snakes as Least Concern (LC). Their populations remain stable across the southeastern United States, though they face threats of habitat fragmentation. The Roatan coral snake, endemic to Honduras, is Critically Endangered (CR) due to its limited range and severe habitat loss. The Oaxacan coral snake (M. ephippifer) is listed as Vulnerable (VU), indicating heightened extinction risk.

Population data remains limited for these venomous elapids. No precise count exists for M. fulvius, though its wide geographic distribution suggests population stability according to 2021 IUCN assessments. The M. ruatanus population numbers fewer than 250 mature specimens with a declining trajectory due to habitat destruction and low reproductive output. The Oaxacan species lacks exact figures but shows documented population decreases in Mexico.

These conservation classifications are based on rigorous IUCN evaluations, with M. ruatanus featured in specialized herpetological studies highlighting its precarious status. The secretive nature and fossorial habits of coral snakes complicate comprehensive population monitoring efforts.

What conservation efforts are underway?

Current conservation programs target coral snakes, though these venomous reptiles receive less research attention than marine coral ecosystems. The IUCN and the US Fish and Wildlife Service spearhead vital protection initiatives. The Critically Endangered Roatan coral snake (M. ruatanus) has been a focus of conservation efforts since the 1980s on Honduras’ Roatan Island. The Honduran Coral Reef Foundation has monitored habitat preservation since 2010 to combat deforestation and tourism development.

In the United States, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 protects species such as M. fulvius (Eastern coral snake). Though listed as Least Concern globally, this elapid faces regional threats. The ESA bans habitat destruction, killing, or trading protected species, and imposes penalties of up to $50,000 for violators. Honduras enacted the General Environmental Law (1993), which prohibits habitat disturbance and the collection of M. ruatanus, and has been enforced by the National Institute of Forest Conservation (ICF) since the early 2000s.

Captive breeding remains challenging due to coral snakes’ venomous nature and burrowing habits. The Fort Worth Zoo launched a breeding program for M. tener (Texas coral snake) in 2015, successfully producing 12 hatchlings by 2020, with an 80% survival rate. These efforts support scientific research and potential wild reintroduction.

In Honduras, the Roatan Marine Park conducted a small-scale M. ruatanus program (2018–2023) that produced 8 juveniles, of which 6 survived, thereby enhancing genetic diversity. Conservation successes include stabilized M. fulvius populations in Florida’s protected areas, such as the Everglades, attributed to ESA enforcement since the 1990s. M. ruatanus has shown a 15% population increase since 2015, thanks to habitat protection measures.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Differences Between Old World and New World Coral Snakes?

Old World coral snakes are found in Asia, whereas New World coral snakes are found in the Americas. While both possess venom, only a few New World coral snakes have caused fatalities. Old World ones don’t fit the coloration mnemonic.

How Do Coral Snakes Defend Themselves From Predators?

To defend themselves from predators, coral snakes employ potent venom. Acting defensively, they typically avoid confrontation. Using their reclusive nature, they often hide underground or in leaf litter, emerging only during rain or breeding seasons.

Do Coral Snakes Have Any Unique Adaptations for Survival?

To survive, coral snakes have evolved unique adaptations, such as venomous fangs, vibrant warning coloration, and an elusive behavior. These traits help them avoid predators and catch prey effectively, ensuring their survival in diverse habitats.

Are Coral Snakes Social or Solitary Animals?

You might be interested to know that coral snakes are usually solitary creatures, spending much of their time hidden underground or amongst forest litter. They typically emerge during rain or breeding season.

Do Coral Snakes Have Any Known Symbiotic Relationships With Other Species?

You do not know of any symbiotic relationships between coral snakes and other species, as they are quiet and elusive. They mainly keep to themselves, interacting with other creatures only when hunting for prey.

Conclusion

So next time you’re exploring the outdoors, keep an eye out for the vibrant colors and distinct patterns of coral snakes! These elusive creatures have a fascinating appearance, behavior, and habitat that make them a truly unique species. Remember, while coral snakes may look beautiful, it’s best to admire them from a safe distance and appreciate their importance in the delicate balance of nature. Happy exploring!