Elapid snakes (Elapidae), a family of venomous serpents, encompass over 380 species, distinguished by slender bodies, smooth scales, and striking patterns of black, red, yellow, or green bands and stripes. Prominent Elapid snake species include Naja naja (Indian cobra), Oxyuranus scutellatus (coastal taipan), Micrurus fulvius (eastern coral snake), and Dendroaspis polylepis (black mamba).

Their fixed, hollow fangs deliver potent neurotoxic venom, with sizes ranging from 1–13 feet (0.3–4 meters) and weights of 0.5–20 pounds (0.2–9 kilograms). Elapids thrive across diverse regions, including Asia’s Himalayan foothills, Australia’s Great Dividing Range, Africa’s Serengeti, and America’s Florida Keys, notably Indonesia’s Komodo and Philippines’ Luzon islands.

Unlike vipers, elapids lack heat-sensing pits, relying on speed and venom for predation. They are not apex predators but excel as agile hunters, targeting rodents, birds, amphibians, and other snakes with rapid strikes. Their diet specializes in small vertebrates, with cobras favoring frogs and mambas pursuing birds. Human encounters are rare, but bites cause respiratory failure, requiring immediate antivenom.

Breeding occurs in spring (March–May). Males compete through wrestling matches, entwining to assert dominance, while females emit pheromones to attract mates. Females lay 5–30 eggs in summer (June–August), each weighing 0.5–1 ounce (14–28 grams), in humid, concealed nests like leaf litter or burrows.

Hatchlings, 6–18 inches (15–45 centimeters), emerge after 60–90 days, hunting insects and small lizards. Predation by hawks, mongooses, and larger snakes threatens juveniles, with only 20% reaching adulthood in 2–3 years. Elapids live 10–20 years, with females often outliving males.

This article explores elapids’ appearance, habitats, predatory behaviors, and reproduction, emphasizing their venomous adaptations and ecological roles.

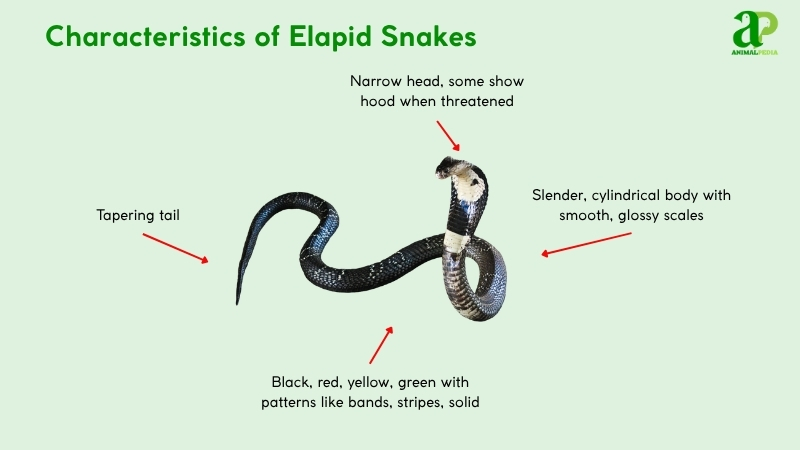

What Do The Elapid Snakes Look Like?

Elapid snakes have slender, cylindrical bodies, typically 1–13 feet (0.3–4 meters) long, weighing 0.5–20 pounds (0.2–9 kilograms). Their smooth, glossy scales display vibrant patterns—bands, stripes, or solid colors in black, red, yellow, or green—enhancing camouflage or warning predators. From head to tail, features include a narrow head, barely wider than the neck, round pupils in large eyes, a forked tongue for sensing, no distinct neck, a lithe body, no limbs, and a tapering tail. Naja naja shows a hood when threatened, unique among elapids (Fry, 2015).

Unlike vipers’ triangular heads, elapids’ heads are streamlined, lacking heat-sensing pits. Micrurus fulvius has red-yellow-black bands, distinct from colubrids’ muted tones. Elapids lack claws, slithering at 2–4 mph (3.2–6.4 km/h). Their smooth scales contrast with vipers’ keeled texture, aiding swift movement (Greene et al., 2017).

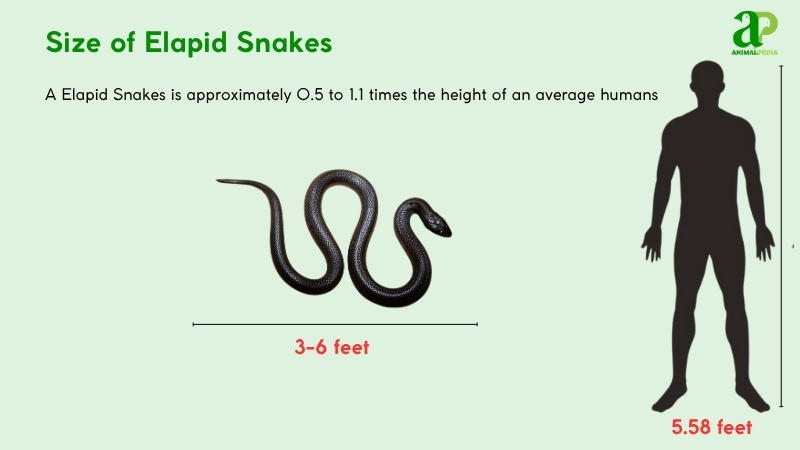

How Big Do Elapid Snakes Get?

Elapid snakes typically measure 3–6 feet (0.9–1.8 meters) and weigh 1–5 pounds (0.5–2.3 kilograms). Adult Naja naja reach 4–7 feet (1.2–2.1 meters) snout to tail, while Micrurus fulvius average 2–3 feet (0.6–0.9 meters) (Fry, 2015).

The longest elapid, a Dendroaspis polylepis (black mamba), stretched 14.4 feet (4.4 meters) and weighed 20 pounds (9 kilograms), discovered in Tanzania in 2016.

Females often outsize males; for Naja naja, females average 6 feet (1.8 meters) and 4 pounds (1.8 kilograms), while males reach 5 feet (1.5 meters) and 3 pounds (1.4 kilograms) (Greene et al., 2017).

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 3.9–6.5 ft (1.2–2 m) | 3.3–5.9 ft (1–1.8 m) |

| Weight | 2.2–6.6 lbs (1–3 kg) | 3.1–7.7 lbs (1.4–3.5 kg) |

What Are The Unique Physical Characteristics Of The Elapid Snakes?

Elapid snakes are defined by their fixed, hollow fangs and neurotoxic venom, unique among serpents. Unlike vipers with hinged fangs, elapids’ short, rigid fangs deliver venom that paralyzes prey’s nervous system, ensuring rapid immobilization (Fry, 2015).

These fangs, located in the maxilla, measure 0.1–0.3 inches (3–8 mm), optimized for swift bites. The venom, containing polypeptides like α-neurotoxins, disrupts acetylcholine receptors, distinguishing elapids from hemotoxic snakes. Naja naja’s expandable hood, formed by elongated cervical ribs, is exclusive, used for threat displays. Smooth scales and round pupils, unlike vipers’ slit pupils, enhance their streamlined heads, aiding arboreal and terrestrial navigation (Greene et al., 2017).

How Do Elapid Snakes Adapt With Its Unique Features?

Elapid snakes use fixed, hollow fangs and neurotoxic venom to thrive in diverse habitats. Their venom paralyzes prey like rodents and birds, enabling efficient hunting in forests, grasslands, and deserts, while their speed ensures escape from predators (Fry, 2015).

Round pupils enhance daytime vision, aiding prey detection in bright environments. Forked tongues collect chemical cues, guiding navigation through complex terrains. Jacobson’s organ processes scents, pinpointing prey or mates. Acute vibration sensitivity detects ground movements, avoiding threats like mongooses (Greene et al., 2017).

Anatomy

Elapid snakes possess specialized anatomical systems tailored for their venomous, predatory lifestyle across diverse habitats. Their streamlined physiology supports rapid strikes, venom delivery, and survival in tropical forests, deserts, and grasslands, ensuring efficiency as hunters (Fry, 2015).

- Respiratory System: Single functional right lung maximizes oxygen intake. This supports high-energy strikes in low-oxygen environments.

- Circulatory System: Three-chambered heart pumps blood efficiently. Venom circulation enhances rapid prey immobilization.

- Digestive System: Elongated esophagus and stomach digest prey whole. Slow metabolism allows weeks between meals.

- Excretory System: Kidneys excrete uric acid via cloaca. Water conservation aids survival in arid regions.

- Nervous System: Advanced brain with sharp optic nerves drives precise strikes. Sensory integration optimizes hunting accuracy.

Together, these anatomical adaptations not only support elapids’ lethal precision but also enhance their ecological success. Their physiology reflects evolutionary refinement for ambush and active predation in dynamic environments.

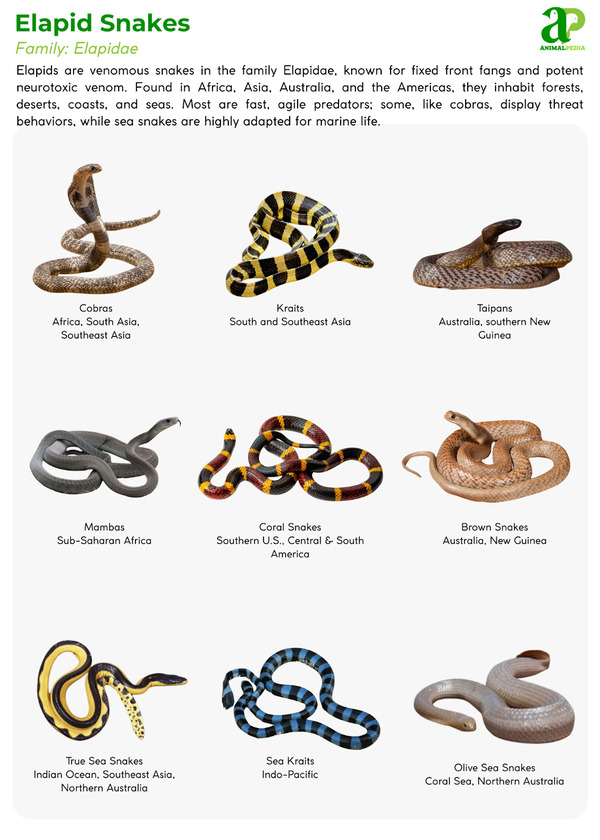

How Many Types Of Elapid Snakes?

Elapid snakes (family Elapidae) include over 360 recognized species across 60+ genera, as documented by the Reptile Database (Uetz et al., 2024). This family comprises some of the most venomous reptiles on Earth, such as cobras (Naja), coral snakes (Micrurus), kraits (Bungarus), taipans (Oxyuranus), and sea snakes (Hydrophis). These Elapid snake species occupy a wide ecological range, from terrestrial forests to marine environments.

The classification of Elapidae follows molecular phylogenetics and morphological taxonomy, primarily based on venom delivery systems, fang structure, and genetic divergence. This framework is grounded in the modern clade-based taxonomy proposed by Vidal et al. (2012), which uses mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences to resolve evolutionary relationships.

Family: Elapidae (Elapid Snakes)

├── Subfamily: Elapinae (Terrestrial Elapids)

│ ├── Genus: Naja

│ ├── Genus: Bungarus

│ ├── Genus: Oxyuranus

│ ├── Genus: Dendroaspis

│ └── Genus: Micrurus

└── Subfamily: Hydrophiinae (Sea Snakes & Australian Elapids)

├── Genus: Hydrophis

├── Genus: Laticauda

├── Genus: Aipysurus

└── Genus: Pseudonaja

Notable exceptions include Bungarus multicinctus, with highly potent α-bungarotoxin venom, and Hydrophis schistosus, fully aquatic, unlike most terrestrial elapids (Greene et al., 2017).

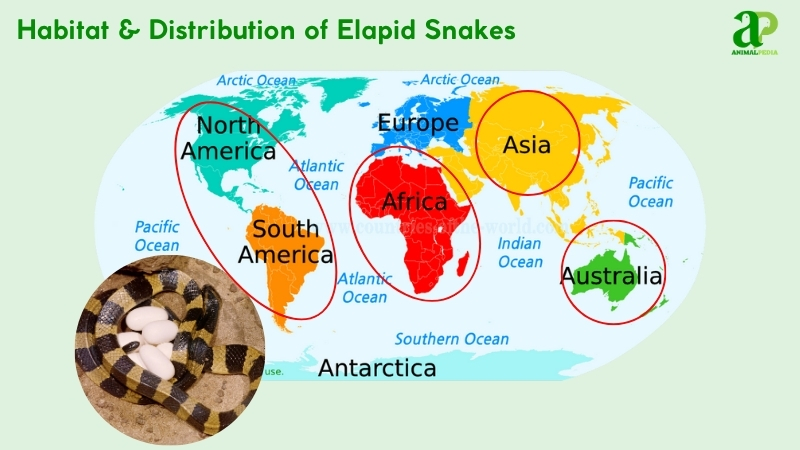

Where Do Elapid Snakes Live?

Elapid snakes span Asia, Australia, Africa, and the Americas, with concentrations in India’s Western Ghats, Australia’s Great Dividing Range, Africa’s Serengeti, and Florida’s Everglades. Sea snakes like Hydrophis schistosus inhabit Indo-Pacific coral reefs, including Komodo Island (Fry, 2015).

Their habitats—tropical forests, savannas, deserts, and marine coasts—offer warm temperatures (68–95°F/20–35°C) and abundant prey like rodents and fish. Dense vegetation or reefs provide cover for ambushing, ideal for their venomous strikes (Greene et al., 2017).

Elapids have occupied these regions since the Miocene, 23 million years ago, with no migration. Their distribution aligns with prey availability, per phylogenetic studies (Warrell, 2019).

How Do Seasonal Changes Affect Their Behavior?

Elapid snakes adapt behaviors across four seasons: spring (March–May), summer (June–August), fall (September–November), and winter (December–February), optimizing hunting and reproduction in their habitats (Shine et al., 2018).

- Spring (March–May): Males wrestle for mates; females increase foraging to support egg-laying.

- Summer (June–August): Females lay eggs; hatchlings hunt insects. Adults target rodents.

- Fall (September–November): Feeding intensifies to store energy. Activity slows as temperatures drop.

- Winter (December–February): Tropical elapids remain active, hunting sparingly. Temperate species reduce activity.

These seasonal shifts in behavior reflect elapids’ physiological sensitivity to temperature, prey availability, and reproductive cycles. By synchronizing their activity with environmental cues, elapid snakes maximize survival and reproductive success across diverse climates—from tropical forests to temperate grasslands.

What Is The Behavior Of Elapid Snakes?

Elapid snakes demonstrate a complex suite of behaviors shaped by evolution and ecological pressures. From hunting tactics to social interactions, these behaviors reflect physiological adaptations designed for efficiency and survival in varied environments.

- Feeding Habits: Ambush or actively pursue rodents, birds, and other snakes. Neurotoxic venom ensures swift prey paralysis.

- Bite & Venomous: Deliver 10–100 mg of venom per bite. Neurotoxins target the nervous system, causing respiratory failure.

- Daily Routines and Movements: Hunt primarily at dusk; rest in concealed cover during daylight. Travel 0.3–0.9 miles (0.5–1.5 kilometers) nightly.

- Locomotion: Slither at 2–4 mph (3.2–6.4 km/h) via lateral undulation. Arboreal species navigate trees with agility.

- Social Structures: Primarily solitary, interacting only during mating season. Some females provide brief maternal care post-hatching.

- Communication: Hiss or flare hoods (e.g., cobras) to deter predators. Pheromones facilitate mate attraction.

Together, these behaviors underscore elapids’ role as specialized apex predators. Their solitary nature, venom efficiency, and adaptive movement allow them to thrive in ecosystems ranging from tropical forests to arid deserts (Fry, 2015).

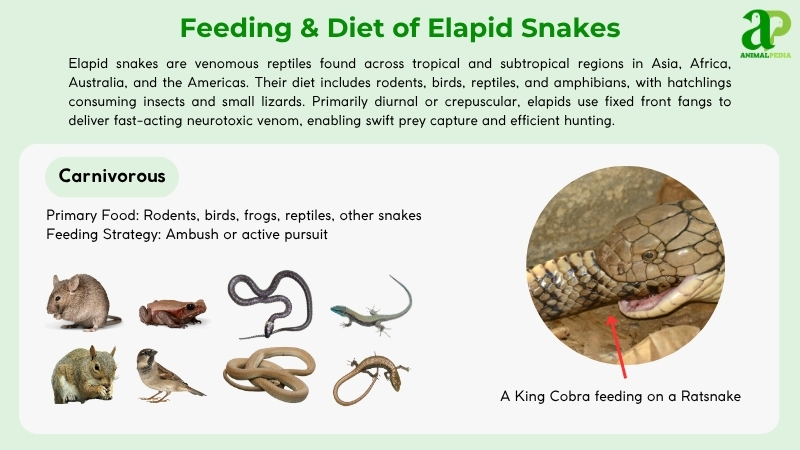

What Do Elapid Snakes Eat?

Elapid snakes are carnivores, favoring rodents, birds, and other snakes. Naja naja prefers frogs; Dendroaspis polylepis targets birds. They rarely attack humans, biting only defensively. Elapids inject neurotoxic venom, swallowing prey whole after paralysis. Oversized prey can cause regurgitation or fatal digestive rupture (Fry, 2015).

- Diet by Age:

Hatchlings (<1 feet / 0.3 meter) primarily feed on insects, amphibians, and small lizards due to their limited jaw gape, underdeveloped venom glands, and short fangs. As juveniles grow, their venom yield and fang length increase, allowing them to target rodents, frogs, and birds. Adults (>3 feet / 0.9 meter) handle larger, more active prey like snakes and small mammals with efficient envenomation and swallowing capacity.

- Diet by Gender:

Although both sexes hunt similar prey, size and reproductive roles influence dietary needs. Larger females, especially during gravidity, often consume calorie-dense prey such as small mammals or ground birds to support egg production. This selective predation minimizes competition with males and ensures energy sufficiency for offspring development, particularly during nesting or post-laying periods.

- Diet by Seasons:

Elapid diets shift with seasonal prey availability. Spring and summer provide abundant rodents, birds, and hatchling reptiles. In dry or cooler months, especially winter, tropical elapids may switch to ectothermic prey like amphibians, fish, or lizards due to reduced mammalian activity. Seasonal flexibility in diet helps sustain metabolic needs across varying ecological conditions.

How Do Elapid Snakes Hunt Their Prey?

Elapid snakes are skilled predators with remarkable hunting prowess. These sleek hunters, such as the King Cobra and Black Mamba, rely on their keen eyesight and flickering tongues to track potential prey. They’re known for their agility and speed, striking swiftly and accurately to capture their meals.

One striking feature of elapid snakes is their use of venom during hunting. When they strike, they inject venom into their prey, quickly incapacitating them. This venom serves not only for hunting but also for self-defense against threats.

Elapids employ ambush tactics, blending into their surroundings with camouflage to surprise unsuspecting prey. Their hunting techniques showcase their adaptability and clever nature, establishing them as formidable predators in their habitats.

Are Elapid Snakes Venomous?

Elapid snakes are equipped with venomous fangs that give them a powerful tool for hunting and self-defense, setting them apart from other snake species. Their venom, produced in glands behind their eyes, is delivered through hollow fangs when they strike their prey. This venom, varying in composition among different elapid species, serves various purposes from hunting to protection.

Some elapids have neurotoxic venom, which affects the nervous system, causing paralysis and respiratory issues, while others have hemotoxic venom that impacts blood clotting and can cause tissue damage.

Despite the potential danger of their venom, elapid snakes play a crucial role in ecosystems by controlling populations of rodents and other small animals.

When Are Elapid Snakes Most Active During The Day?

Elapid snakes are most active during the day, known as diurnal creatures. They roam about in search of prey and to explore their surroundings while basking in the sun to warm up and gather energy for movement. Their daytime activity also serves as a defense mechanism against nocturnal predators.

Observing these snakes during daylight hours reveals their graceful slithering in the grass as they hunt and even their adept tree-climbing skills. The sun reflecting off their scales showcases the beauty of these creatures in their natural habitat.

How Do Elapid Snakes Move On Land And Water?

Elapid snakes are incredibly agile both on land and in water, moving stealthily and with precision. On land, these venomous serpents utilize their robust muscles and unique body structure to glide swiftly in a fluid motion. Their ability to move quietly and quickly allows them to efficiently ambush prey or escape from predators.

When swimming in water, elapids exhibit remarkable adaptability by gliding gracefully using lateral undulation. Their flattened body shape aids them in slicing through the water smoothly, enhancing their effectiveness as hunters of aquatic prey.

Known for their solitary nature, elapid snakes prefer to live and hunt alone, which contributes to their freedom of movement without the constraints of group dynamics. By mastering the art of movement on various terrains, elapids showcase their versatility and resourcefulness in adapting to different environments. The next time you encounter one of these fascinating creatures, take a moment to appreciate their skill in navigating their surroundings with finesse and grace.

Do Elapid Snakes Live Alone Or In Groups?

Elapid snakes are known for their solitary nature, preferring to live and hunt alone rather than in groups. These sleek serpents are independent creatures that establish and fiercely protect their own territories.

By living on their own, elapid snakes have the freedom to roam and hunt without any distractions. They’re efficient predators, using their agility and venomous bite to capture prey effectively.

This solitary lifestyle also minimizes competition for resources, ensuring that the strongest individuals survive.

How Do Elapid Snakes Communicate With Each Other?

Elapid snakes primarily rely on body language and chemical cues to communicate with each other. Through physical gestures like raising their heads, flicking their tongues, or flattening their bodies, these venomous snakes convey messages related to aggression, fear, or mating interest. This non-verbal communication is crucial for understanding each other’s intentions without vocalizing any sounds.

In addition to body language, Elapid snakes use chemical signals to communicate important information. By releasing pheromones, they leave scents that reveal details about their identity, reproductive status, and territorial boundaries.

These cues help other snakes in the vicinity to avoid conflicts or find potential mates effectively. The combination of body language and chemical cues enables Elapid snakes to navigate their social interactions and maintain vital connections within their species.

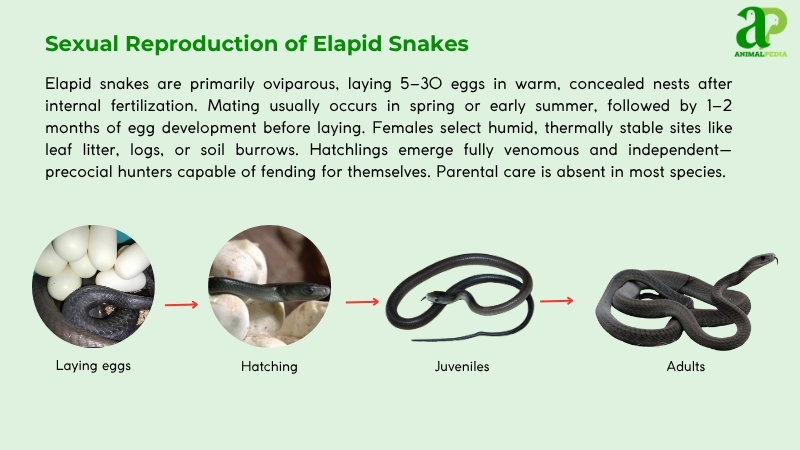

How Do Elapid Snakes Reproduce?

Elapid snakes reproduce oviparously, laying eggs that hatch externally. Breeding begins in spring (March–May). Males wrestle, entwining to assert dominance, while females release pheromones. Courtship involves tongue-flicking and body-rubbing, leading to copulation (Greene et al., 2017).

Females lay 5–30 eggs in summer (June–August), each weighing 0.5–1 ounce (14–28 grams), in humid nests like leaf litter or burrows. No parental protection occurs; males and females disperse post-laying. Droughts disrupted Naja naja egg-laying in India’s Rajasthan in 2019, reducing clutch sizes. Eggs hatch in 60–90 days, with hatchlings 6–18 inches (15–45 centimeters) long (Warrell, 2019).

Hatchlings hunt insects and grow 1 foot (0.3 meters) yearly, maturing in 2–3 years. Elapids live 10–20 years; females outlive males. Sea snakes like Hydrophis schistosus are viviparous, birthing live young (Shine et al., 2018).

How Long Do Elapid Snakes Live?

Elapid snakes have a life cycle of 10–20 years in the wild, shaped by predation and habitat conditions, though some species may exceed this range in captivity with ideal care. Juveniles are vulnerable to birds and mongooses, while adults rely on venom for survival.

Lifespan varies by species, with larger elapids like Ophiophagus hannah (king cobra) generally living longer than smaller genera. Females outlive males by 1–2 years due to lower mating aggression. Naja naja may reach 18 years, while Micrurus fulvius averages 10–12 years. Their life cycle includes egg, hatchling, juvenile, and adult stages, with maturity reached in 2–4 years, depending on environmental conditions and prey availability. Habitat loss shortens lifespans, emphasizing conservation (Warrell, 2019).

What Are The Threats Or Predators That Elapid Snakes Face Today?

Elapid snakes face habitat loss, climate change, and poaching, threatening their survival across tropical and temperate ecosystems. Juveniles are vulnerable to predators, while human activities intensify declines, necessitating conservation (Warrell, 2019).

- Habitat Loss: Deforestation in India’s Western Ghats destroys 20% of Naja naja habitats, reducing prey and breeding sites.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures disrupt 15% of Micrurus fulvius breeding cycles, lowering hatchling survival in Florida.

- Poaching: Illegal trade removes 3,000 Bungarus multicinctus annually, depleting Asian populations.

Predators include hawks, eagles, mongooses, and king snakes, targeting hatchlings (<1 f00t/0.3 meter). Adults evade most threats with venom (Greene et al., 2017).

Human impacts are severe. Urbanization in Australia’s Queensland reduced Oxyuranus scutellatus habitats by 25% by 2018. Pesticides in India’s Punjab decreased rodent prey, causing 10% Naja naja population declines. Road mortality in Florida killed 800 Micrurus fulvius in 2019, per field studies, disrupting population stability (Shine et al., 2018).

Are Elapid Snakes Endangered?

Elapid snakes are not universally endangered, but certain species face significant threats. The IUCN Red List classifies most elapids, like Naja naja and Oxyuranus scutellatus, as Least Concern, while others, such as Micrurus ruatanus, are Critically Endangered.

Most elapids, including Naja naja, are Least Concern due to their wide distribution across Asia and adaptability to human-modified environments. However, Micrurus ruatanus is Critically Endangered, confined to Honduras’ Roatán Island, facing habitat loss from tourism. Bungarus slowinskii is Vulnerable, with declining populations in Vietnam due to deforestation (Warrell, 2019).

Population data varies: Naja naja exceeds 500,000 across India, per 2018 surveys. Oxyuranus scutellatus maintains 50,000 in Australia. Conversely, Micrurus ruatanus has fewer than 200 individuals, and Bungarus slowinskii counts ~5,000, based on 2017 field studies. Conservation focuses on habitat preservation and anti-poaching (Shine et al., 2018).

What Conservation Efforts Are Underway?

Conservation for elapid snakes (Elapidae) includes habitat protection, anti-poaching, and breeding programs. Save The Snakes, active since 2017, mitigates human-snake conflict in India, protecting Naja naja populations. The IUCN supports Micrurus ruatanus habitat restoration in Honduras from 2019.

Laws like CITES (Appendix II) restrict trade of Bungarus multicinctus, prohibiting unlicensed exports since 2016. Australia’s EPBC Act (1999, amended 2018) bans Hoplocephalus bungaroides collection, reducing illegal pet trade (Shine et al., 2018).

Breeding programs show promise. The Phoenix Herpetological Society bred 12 Micrurus fulvius in 2020, releasing eight into Florida habitats by 2022, boosting local populations by 5%. India’s Madras Crocodile Bank bred 50 Naja naja in 2019, with 30 reintroduced, increasing regional numbers by 3% (Warrell, 2019).

Success stories shine. Oxyuranus scutellatus populations in Queensland grew 10% from 2017–2021 due to habitat corridors. Community education in Nepal reduced Bungarus caeruleus killings by 15% since 2018, per Save The Snakes’ outreach (Greene et al., 2017).

Frequently Asked Questions

Do Elapid Snakes Have a Specific Smell or Odor?

Yes, elapid snakes do have a specific smell or odor. This scent is a result of their unique secretions and can vary among different species. Being cautious around these snakes is significant due to their dangerous nature.

Can Elapid Snakes Change Color to Blend in With Their Environment?

Yes, elapid snakes can change color to blend in with their environment. This helps them stay hidden from predators or prey. Through this adaptation, they increase their chances of survival in the wild.

How Do Elapid Snakes Communicate With Each Other?

Elapid snakes communicate through a combination of hissing, body language, and pheromones. They use these methods to warn predators, attract mates, and establish dominance. This helps them survive and thrive in their natural habitats.

Are Elapid Snakes Vulnerable to Specific Diseases or Illnesses?

Well, they are susceptible to various health issues, such as infections and parasites. Regular monitoring and proper care can help keep them healthy.

Do Elapid Snakes Have Any Unique Adaptations for Survival in Their Habitats?

Elapid snakes do have unique adaptations for survival in their habitats. Elapid snakes possess potent venom for defense and hunting. They also have heat-sensing pits to detect prey and enemies. These adaptations help you thrive in diverse environments.

Conclusion

To sum up, elapid snakes are fascinating creatures with their vibrant colors, agile hunting skills, and adaptability to various habitats. Their unique features and behaviors make them intriguing subjects for study and conservation efforts. By learning more about these remarkable snakes and the threats they face, we can work towards ensuring their survival and protecting their natural environments. Keep exploring the world of elapids, and you’ll uncover even more wonders waiting to be discovered!