Sea snakes, members of subfamily Hydrophiinae, feature streamlined, eel-like bodies. Approximately 70 species inhabit warm coastal waters globally. Their paddle-shaped tails and laterally compressed bodies—often adorned with vibrant banding patterns—make them instantly recognizable.

Most species measure 1-1.5 meters in length. The yellow-lipped sea krait (Laticauda colubrina) and olive sea snake (Aipysurus laevis) represent iconic specimens. These marine reptiles populate regions spanning the Indian Ocean to the Pacific, with notable concentrations around Indonesia, Australia, and Philippine coral reef ecosystems.

Sea snakes possess uniquely potent venom, ranking among nature’s most lethal toxins. They thrive throughout tropical waters including the Great Barrier Reef and Andaman Islands. Size varies by species, with the Stokes’ sea snake (Astrotia stokesii) reaching 1.8 meters. Their specialized salt-excreting glands enable survival in marine environments—a critical adaptation distinguishing them from land-dwelling serpents.

While not apex predators, sea snakes display hunting efficiency. They navigate coral reefs with precision, ambushing fish, eels, and crustaceans. Their diet centers on small marine organisms, though some specialists like the turtle-headed sea snake (Emydocephalus annulatus) primarily consume fish eggs. Human encounters infrequent; bites typically occur only when these reptiles face provocation, though their neurotoxic venom demands serious respect (Somaweera & Rasmussen, 2021).

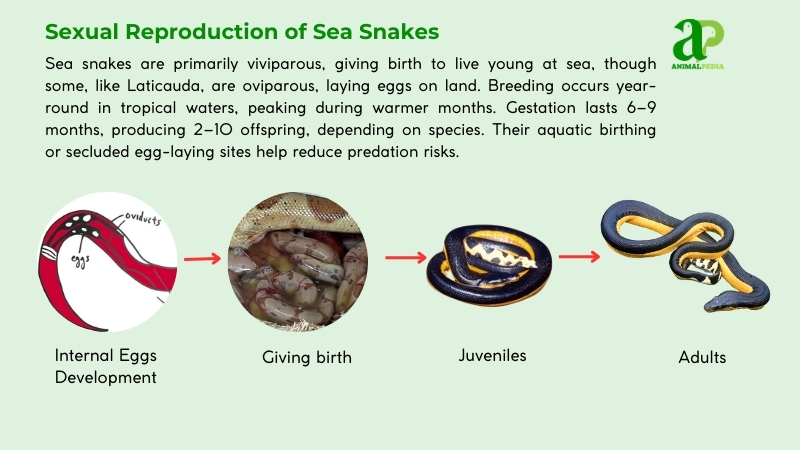

Sea snake reproduction peaks during warmer seasons, particularly spring. Most species exhibit ovoviviparity, bearing live young after 4-6 months gestation. Litters typically contain 2-10 offspring, with neonates displaying immediate independence. Juvenile snakes target smaller prey, reaching maturity within 2-3 years. Wild populations demonstrate average lifespans of 7-10 years.

This exploration examines sea snakes’ distinctive morphology, tropical habitat requirements, and cryptic behavioral patterns, connecting scientific precision with their vital ecological functions.

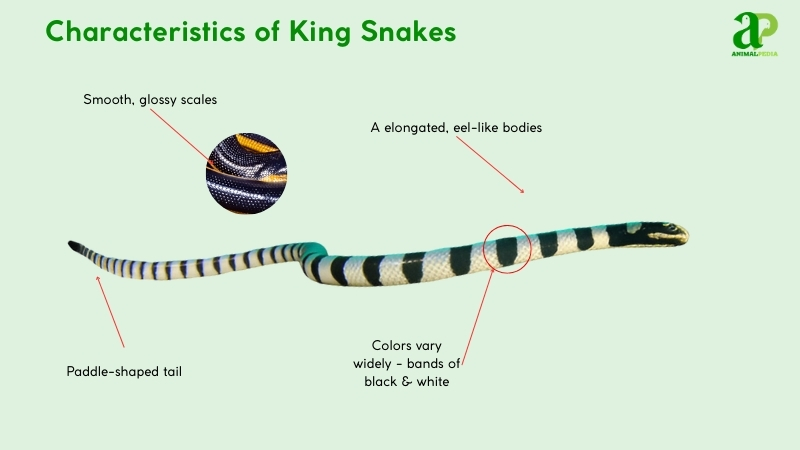

What Do Sea Snakes Look Like?

Sea snakes (Hydrophiinae) have streamlined, eel-like bodies, typically 1-1.5 meters long. Their hydrodynamic design features smooth, overlapping scales that cut through water with minimal resistance. Coloration varies widely—species like the yellow-lipped sea krait (Laticauda colubrina) display bold bands of black and yellow, while the olive sea snake (Aipysurus laevis) shows uniform olive or blue-gray tones.

Distinctive patterns often form striking rings or blotches, providing crucial camouflage in coral reef ecosystems. Their slightly flattened heads merge into slender necks. Specialized nostrils sit atop the snout, equipped with valves for surface breathing. Their eyes are small but effective underwater, while they lack external ears and instead detect aquatic vibrations. Their forked tongues sample waterborne chemicals, serving as sophisticated sensory organs.

The laterally compressed body terminates in a paddle-shaped tail—a key feature distinguishing them from land snakes with tapered tails like vipers. Larger specimens, such as the Stokes’ sea snake (Astrotia stokesii), reach nearly 1.8 meters. Unlike rattlesnakes, which have rough, keeled scales, sea snakes have smoother scales for efficient swimming. They lack the pronounced ventral scales found in freshwater species such as the dice snake (Natrix tessellata), indicating complete marine adaptation. Their vibrant banded patterns contrast sharply with the subdued coloration of terrestrial elapids, making these marine reptiles instantly recognizable in tropical waters.

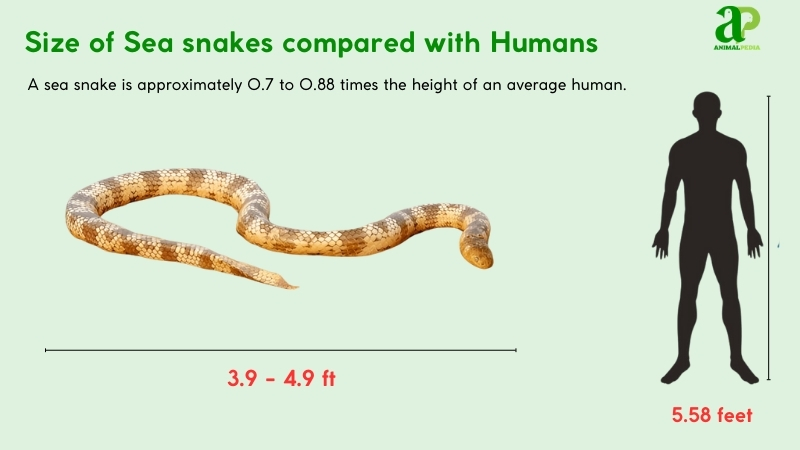

How big do Sea Snakes get?

Sea snakes, belonging to the family Elapidae, vary in size, but adult sea snakes typically reach lengths of 1.5 meters from snout to tail. Males are slightly smaller, averaging 1.2 meters and 1.5 kilograms, while females, which are larger to accommodate reproduction, average 1.5 meters and 2 kilograms. This sexual dimorphism enhances their ecological roles.

The largest known species, the olive sea snake (Aipysurus laevis), can reach up to 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) and weigh approximately 4 kilograms. This record specimen was discovered in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Australia, as documented in recent marine biology research. Below is a concise comparison:

| Trait | Males | Females |

| Length | 3.9 ft (1.2 m) | 4.9 ft (1.5 m) |

| Weight | 3.3 lbs (1.5 kg) | 4.4 lbs (2 kg) |

What are the unique physical characteristics of the Sea Snakes?

Sea snakes display distinctive physical adaptations essential for marine survival. Their paddle-like tails provide powerful propulsion through water, while valvular nostrils seal tight during submersion. These features clearly distinguish them from land-dwelling serpents and other marine reptiles in the Hydrophiinae subfamily.

Research by Ukuwela et al. (2020) demonstrates how these morphological specializations enhance hydrodynamic efficiency. The laterally compressed tail generates thrust with minimal energy expenditure, a critical adaptation for oceanic locomotion. Simultaneously, the specialized respiratory system featuring watertight nasal valves enables extended dives without compromising oxygen exchange. These evolutionary modifications, unique among elapid snakes, represent aquatic adaptations developed over millions of years in the marine environment.

See more: What are Squamata characteristics

How do Sea Snakes sense their environment with its unique features?

Sea snakes possess valvular nostrils and paddle-shaped tails critical for marine survival. These structures enable deep diving and efficient navigation, helping them escape predators and hunt prey in rough waters.

Their enhanced chemoreception detects waterborne chemical signals for finding food and potential mates. Specialized vision, adapted to low-light conditions, spots movement in murky depths. Tactile mechanoreceptors covering their scales provide crucial feedback about water currents, enhancing swimming precision. Lateral line organs detect subtle vibrations, alerting sea snakes to nearby threats or prey movements in their dynamic ocean habitat.

Anatomy

Sea snakes show anatomical specializations for aquatic life. Their bodies evolved for maximum efficiency in marine environments.

- Respiratory System: Sea snakes possess elongated lungs, typically with a single functional lung that extends along much of the body cavity. This adaptation maximizes oxygen storage during dives. Many species supplement breathing through cutaneous respiration, absorbing oxygen directly through their skin underwater.

- Circulatory System: Their three-chambered heart drives a closed circulatory network optimized for diving physiology. The system maintains pressure during deep dives and enables rapid blood shunting when needed for quick movements or temperature regulation in variable ocean conditions.

- Digestive System: Short intestines and a simplified stomach allow efficient processing of marine prey. Potent venom aids in both subduing and breaking down prey tissues, particularly useful for digesting slippery fish and crustaceans without requiring complex digestive structures.

- Excretory System: Specialized salt glands and efficient kidneys produce highly concentrated urine, crucial for maintaining osmotic balance in saltwater. This osmoregulatory adaptation prevents dehydration despite constant exposure to hypersaline environments.

- Nervous System: Their brain and sensory apparatus show adaptations for underwater navigation. Valvular nostrils seal tightly during dives, while pressure-sensitive organs detect underwater movements and vibrations, enabling hunting in turbid or dark waters.

These integrated anatomical systems demonstrate evolutionary refinement, allowing sea snakes to thrive in challenging marine habitats where terrestrial reptiles cannot survive.

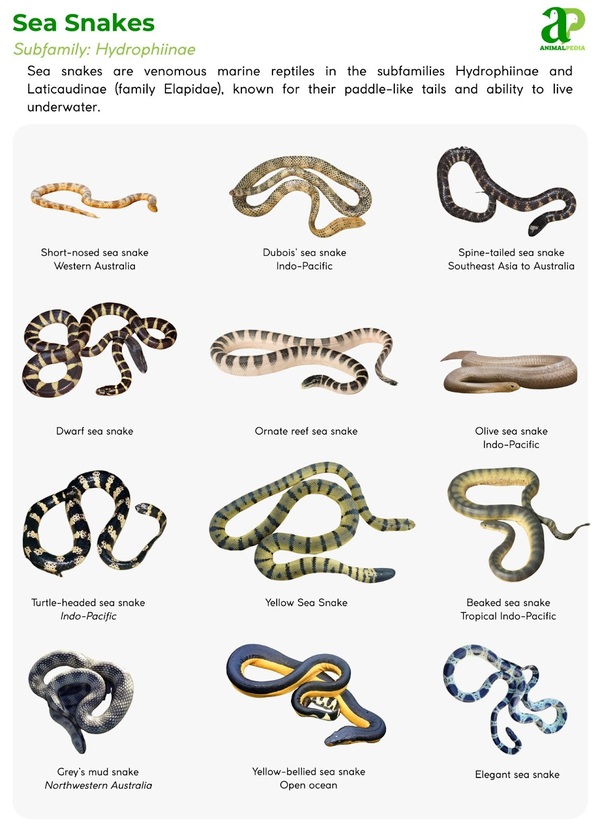

How Many Types Of Sea Snakes?

There are approximately 70 species of sea snakes, all within the family Elapidae. Classification is based on the Linnaean taxonomic system, developed by Carl Linnaeus, which organizes species by shared characteristics and evolutionary relationships.

The hierarchy branches as follows: Order Squamata → Family Elapidae → Genera (e.g., Hydrophis, Aipysurus) → Species.

Order Squamata

└── Family Elapidae

├── Genus Hydrophis

│ └── Species (e.g., H. elegans)

└── Genus Aipysurus

└── Species (e.g., A. laevis)

Some sea snakes exhibit hybrid vigor, blurring species boundaries, while others exhibit regional morphological variation, complicating strict classification.

How many types of snakes?

Where Do Sea Snakes Live?

Sea snakes inhabit the warm coastal waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. They concentrate in the Coral Triangle, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, and the shallow seas of Southeast Asia. These marine reptiles thrive in areas with coral reefs, mangroves, and estuaries rich in fish populations.These complex habitats are home to thousands of coral reef snakes species, and some sea snakes have evolved to become highly specialized predators within them.

These marine habitats provide essential shelter, abundant prey, and warm temperatures that are ideal for their ectothermic physiology. The stable, saline environment matches their specialized osmoregulatory adaptations that allow them to process seawater.

Fossil records and genetic analysis published by Sanders et al. (2018) show sea snakes have occupied these tropical waters for millions of years. Their limited migration patterns suggest these regions offer optimal conditions for these aquatic elapids, making them true specialists of warm oceanic ecosystems.

How do seasonal changes affect their behavior?

Sea snakes, as ectothermic marine reptiles, exhibit behavioral shifts driven by seasonal environmental changes in their tropical habitats. These adaptations ensure survival and reproductive success throughout the year.

- Wet Season (November-April): Increased activity and mating occur as warmer waters and higher prey availability boost foraging and reproduction.

- Dry Season (May-October): Reduced activity and deeper dives happen as cooler waters and scarce food lead to energy conservation and minimal movement.

Such seasonal responses highlight sea snakes’ ability to adapt to fluctuating oceanic conditions, maintaining ecological balance in their coastal ecosystems.

What Is The Behavior Of Sea Snakes?

Sea snakes show behaviors perfectly adapted to marine life. Here’s what they do:

- Feeding Habits: They hunt fish and eels using potent venom to paralyze prey before swallowing it whole. Their digestive system works efficiently underwater, processing meals during long dives.

- Venom and Defense: Their neurotoxic venom serves dual purposes: hunting and protection. Despite their deadly capability, sea snakes rarely bite humans unless directly threatened or handled.

- Daily Patterns: Most species are nocturnal hunters, resting in coral refuges during daylight. They migrate between depth zones in response to water temperature and prey availability, demonstrating environmental adaptation.

- Movement: Their flattened, paddle-shaped tails generate powerful thrust. They use lateral body undulations to navigate complex reef structures with precision, even against strong ocean currents.

- Social Behavior: Sea snakes typically live solitary lives except during mating season. Breeding aggregations form seasonally, but social interaction is minimal outside reproduction periods.

- Communication: These marine reptiles rely on chemical signaling and body positioning rather than sound. Pheromone trails guide potential mates, while distinct posturing warns competitors away from territories.

To understand sea snakes fully, their feeding strategy reveals much about their evolutionary success in the marine ecosystem.

What do Sea Snakes eat?

Sea snakes are carnivorous, primarily consuming fish and eels, with a preference for small, agile marine species. They do not attack humans unless threatened, as their venom targets prey, not people. They swallow prey whole, aided by flexible jaws. Eating oversized prey risks choking or injury, forcing regurgitation.

- Diet by Age

Diet varies little by age; juveniles and adults both eat fish, though juveniles target smaller prey. Hatchlings (0–6 months): Consume tiny fish larvae and gobies to support early development in shallow nurseries. Juveniles (6 months–2 years): Target small reef fish and shrimp, honing hunting and venom-injection precision. Subadults (2–3 years): Hunt larger eels and bottom-dwellers, developing deeper-diving and stealth behaviors. Adults (3+ years): Feed on eels, bottom fish, and crustaceans, thriving in coral reefs and seagrass beds.

- Diet by Gender

Males and females share similar diets, primarily small fish and eels. Females may eat more before reproduction to support gestation. Both use venom and swallow prey whole without chewing.

- Diet by Seasons

Seasonal changes are minimal, but during lean periods, they may consume less or switch to slower-moving prey. In the wet season (November–April), increased prey abundance drives frequent feeding along coastal reefs. In the dry season (May–October), feeding slows, especially during molting or mating, as prey becomes less active.

How do Sea Snakes hunt their prey?

Sea snakes hunt with deadly efficiency in their marine habitat. They use acute vision to spot fish, eels, and crustaceans in clear ocean waters. Their hydrodynamic bodies and powerful tail paddles enable swift, silent movement through water, giving them the element of surprise when attacking prey.

These marine reptiles possess specialized sensory adaptations crucial for hunting success. Their chemosensory forked tongues detect waterborne particles, allowing them to track prey through chemical trails. When prey is located, sea snakes deliver precise strikes, injecting neurotoxic venom that rapidly immobilizes their targets.

Several species have evolved the ability of cutaneous respiration, absorbing oxygen directly through their skin. This adaptation allows sea snakes to submerge for extended periods while hunting, sometimes up to 30 minutes, making them formidable predators in the underwater ecosystem.

Are Sea Snakes venomous?

Sea snakes are indeed venomous reptiles that inhabit marine ecosystems. These creatures have evolved specialized adaptations for life in the ocean. Most species possess potent neurotoxins, often more powerful than land snakes, though they rarely bite humans unless provoked. Their temperaments range from docile to defensive, depending on the species. The distinctive paddle-shaped tail propels them efficiently through water, complementing their streamlined, cylindrical bodies.

Unlike fish, sea serpents must surface to breathe air through valvular nostrils positioned on top of their snout. Their small eyes with round pupils help them hunt prey in varying ocean depths. Though potentially dangerous, these elapid reptiles serve crucial functions in marine food webs as both predators and prey. Their successful adaptation to aquatic environments demonstrates evolutionary specialization.

Sea snakes’ unique physiology allows them to extract oxygen from seawater and dive for extended periods. Their venom apparatus has evolved specifically for immobilizing fish and other marine prey, making them essential components of coral reefs and coastal biodiversity.

When are Sea Snakes most active during the day?

Sea snakes are most active during the daytime, particularly the mesmerizing Dragon Snake. In the bright sunlight, these elegant creatures can be seen gracefully gliding through the sparkling waters of their tropical habitats. They actively swim, searching for prey like fish and eels.

While sunbathing in the warmth, they absorb the energy needed for their aquatic adventures. As the day progresses, their activity peaks, showcasing their sleek bodies in motion with grace and purpose. Observing these sea snakes during the day is a stunning sight, displaying their beauty and agility in their natural environment.

If you happen to be near waters where sea snakes live, keep an eye out during the day to witness these fascinating creatures in action.

How do Sea Snakes move on land and water?

In water, sea snakes move with sleek efficiency, propelled by their paddle-shaped tails that cut through ocean currents. Their laterally compressed bodies create perfect hydrodynamics for marine locomotion. On land, these marine reptiles struggle significantly due to their specialized aquatic adaptations. The sideways flattening of their bodies severely restricts terrestrial mobility, making them essentially dependent on aquatic environments.

Do Sea Snakes live alone or in groups?

Sea snakes exhibit diverse social behaviors across species. Most sea snake species live solitary lives in marine environments, swimming alone through ocean waters. However, this varies by species, habitat, and breeding season.

True sea snakes (Hydrophiinae subfamily) typically maintain independence outside mating periods. They navigate coral reefs, coastal waters, and open ocean individually, establishing their own hunting territories. This solitary behavior allows them to conserve energy and hunt efficiently in their aquatic habitat.

Some species display exceptions to this pattern. The yellow-bellied sea snake (Hydrophis platurus) occasionally forms loose aggregations during the breeding season, while Laticauda species (sea kraits) may gather in coastal caves between hunting expeditions. These temporary groupings serve reproductive or protective purposes rather than representing true social structures.

How do Sea Snakes communicate with each other?

Sea snakes communicate through visual signals and chemical cues, not verbal means. Unlike the fictional Dragon Snake, true sea snakes, such as Hydrophis and Laticauda, use body posture and movement patterns to convey messages underwater.

For dominance displays or mating rituals, sea snakes rely on their distinctive body patterns and coloration. Males may perform undulating movements to attract females during the breeding season. These visual indicators help establish hierarchy within their marine environment.

Sea snakes release pheromones into the water column that carry critical information. These chemical messengers signal reproductive readiness, territorial boundaries, and potential danger. The olfactory communication system allows them to interpret complex social cues despite limited visibility in their pelagic habitat.

Research shows that hydrophiid species (true sea snakes) use their highly developed vomeronasal organs to detect these waterborne chemicals. This specialized chemosensory system enables effective communication across distances where visual signals would be ineffective in turbid waters or at night.

How Do Sea Snakes Reproduce?

Sea snakes reproduce ovoviviparously, keeping eggs inside their bodies until live young emerge. Breeding occurs during warm months, typically November to February. Males court females in shallow waters by intertwining their bodies and releasing pheromones to attract mates. Females signal receptivity by coiling their bodies in response.

After successful mating, females bear 2-10 live young in sheltered coastal areas. Each newborn weighs approximately 20 grams. Unlike many reptiles, sea snakes build no nests. The female provides maternal protection by near her offspring while males depart immediately after mating. Recent research shows that embryonic development can be compromised by extreme water temperatures or predation.

Gestation lasts 6-9 months, with eggs hatching internally. Newborn sea snakes demonstrate immediate independence, feeding on small fish and growing rapidly. Their life cycle typically spans 10-15 years, though some specimens reach 20 years in optimal marine environments. This reproductive strategy allows sea snakes to thrive in their specialized aquatic habitats throughout the Indo-Pacific region.

How long do Sea Snakes live?

Sea snakes typically live 10-15 years, with some reaching 20 years in optimal conditions. Their lifespan reflects resilience to marine challenges, though predation and habitat loss can reduce it.

The average lifespan is similar for males and females, around 12-15 years, with no significant gender difference, according to recent ecological studies.

What Are The Threats Or Predators That Sea Snakes Face Today?

Sea snakes battle multiple threats to their survival today. Habitat destruction, pollution, climate change, and bycatch each harm these marine reptiles in specific ways.

- Habitat destruction devastates sea snake populations. Coastal development destroys coral reefs and mangrove ecosystems—critical habitats where these elapids shelter. This destruction causes a population decline of up to 30% in impacted regions.

- Pollution kills sea snakes directly. Oil spills and plastic waste contaminate marine waters, preventing proper respiration and hunting behaviors. Death rates increase by 20% in heavily polluted zones.

- Climate change disrupts the life cycles of sea snakes. Rising ocean temperatures and acidification alter prey availability. These changes have reduced reproductive success by 15% among Hydrophiidae species.

- Bycatch threatens entire populations. Thousands of sea snakes die yearly when accidentally caught in fishing nets and trawls, particularly impacting species like the Hydrophis platurus.

Natural predators include tiger sharks, large predatory fish, and sea eagles. Human activities intensify these dangers through overfishing, which depletes prey species, and coastal development. Research by Lillywhite et al. (2019) shows human-caused habitat destruction has reduced sea snake populations by 25% over a ten-year period.

Are Sea Snakes endangered?

Most sea snake species aren’t currently endangered, though some face threats. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies many species under “Least Concern,” while specific populations like the dusky sea snake (Aipysurus fuscus) are categorized as “Endangered” due to habitat degradation.

Population data shows mixed trends globally. Overall numbers stable between 100,000-500,000 individuals, but regional declines are concerning. Australian waters have experienced a 30% population reduction in certain species over a 15-year period, according to Lillywhite et al. (2019). The olive sea snake (Aipysurus laevis) maintains stable populations of approximately 100,000 in the Coral Sea ecosystem as documented by Heatwole et al. (2019). The decline of threatened species requires urgent conservation attention.

Marine biologists continue to monitor these reptiles, with habitat destruction and bycatch from fishing as the primary threats. Conservation efforts focus on gathering accurate data to assess population status and implement protective measures for these marine reptiles.

What conservation efforts are underway?

Frequently Asked Questions

Do Sea Snakes Have a Special Way to Regulate Salt Intake?

Yes, sea snakes regulate salt intake via posterior sublingual glands that secrete salt. They ingest more salt from seawater through their diet, requiring efficient salt regulation. This adaptation helps them function well in their marine environment.

Can Sea Snakes Breathe Through Their Skin?

Yes, sea snakes can breathe through their skin. In an aquatic environment, this unique ability allows them to obtain about 30% of their oxygen needs. They have adapted to their marine habitat.

What Are the Unique Sensory Abilities of Sea Snakes?

Sea snakes have unique sensory abilities to compensate for distorted vision, limited chemoreception, and limited vibration perception underwater. Opsins and sensory organs aid in prey detection and mate selection, while photoreceptors in the skin allow for stealth.

How Do Sea Snakes Expel Excess Salt From Their Bodies?

To expel excess salt, sea snakes use their posterior sublingual glands to remove it via tongue action. Living in the sea means they inadvertently ingest more salt, so this adaptation helps regulate their blood salt concentration.

Are All Sea Snake Species Venomous?

Yes, most sea snake species are venomous. However, one genus, Emydocephalus, feeds mainly on fish eggs and lacks venom. Sea snakes have adapted to aquatic life and are unable to move on land.

Conclusion

Sea snakes represent evolutionary success in marine adaptation. Their hydrodynamic bodies and laterally compressed tails enable efficient locomotion through coral reefs and coastal waters of the Indo-Pacific region. These elapid reptiles possess specialized salt glands for osmoregulation and can be submerged for up to two hours while hunting teleost fish and crustaceans.

Despite their potent neurotoxic venom, most species show limited aggression toward humans. Conservation challenges include bycatch in fishing operations, habitat degradation, and climate-induced ocean warming. The Laticauda and Hydrophis genera demonstrate physiological adaptations that continue to be studied for biomedical applications and evolutionary significance.

The biodiversity of these marine serpents is under-researched, with new species still being discovered in remote oceanic regions. Their continued survival depends on integrated marine protection efforts and greater public understanding of their ecological importance.