Vipers, family Viperidae, are venomous snakes encompassing over 340 species, characterized by their broad, triangular heads, hinged fangs, and heat-sensing pits between eyes and nostrils. Prominent species of Vibers include Crotalus atrox (Western diamondback rattlesnake), Vipera berus (European adder), and Daboia russelii (Russell’s viper). Their camouflaged scales, often patterned with diamonds or zigzags, and sizes ranging from 1–7 feet (0.3–2.1 meters) and 0.5–15 pounds (0.2–7 kilograms) are distinctive. Vipers inhabit diverse ecosystems, from North America’s Mojave Desert to Europe’s Scandinavian forests, Asia’s Himalayan foothills, and Sri Lanka’s Knuckles Range, adapting to arid, temperate, and tropical climates.

Though not apex predators, vipers are formidable ambush hunters. They use infrared pits to detect warm-blooded prey, striking rodents, birds, and lizards with hemotoxic venom that disrupts blood clotting. Their diet specializes in small vertebrates, with some species targeting amphibians. Human interactions are uncommon, but bites, though rarely fatal, require immediate antivenom treatment due to severe tissue damage.

Reproduction occurs in spring (March–May). Males engage in ritualized combat dances, intertwining to assert dominance. Females, ovoviviparous, retain eggs internally, birthing 5–20 live young after a 3–4-month gestation. Neonates, 6–12 inches (15–30 centimeters), are independent, hunting insects and small lizards with functional venom glands.

Juveniles face predation from hawks, foxes, and larger snakes, relying on camouflage for survival. They mature in 2–3 years, with females growing slightly larger. Lifespans average 10–20 years, with females often outliving males due to less territorial aggression.

This article examines vipers’ morphology, predatory strategies, global distribution, reproductive biology, and ecological roles, emphasizing their venomous adaptations and survival tactics in varied habitats.

New to snake families? Start with the big picture: characteristics of snake.

What Do The Vipers Look Like?

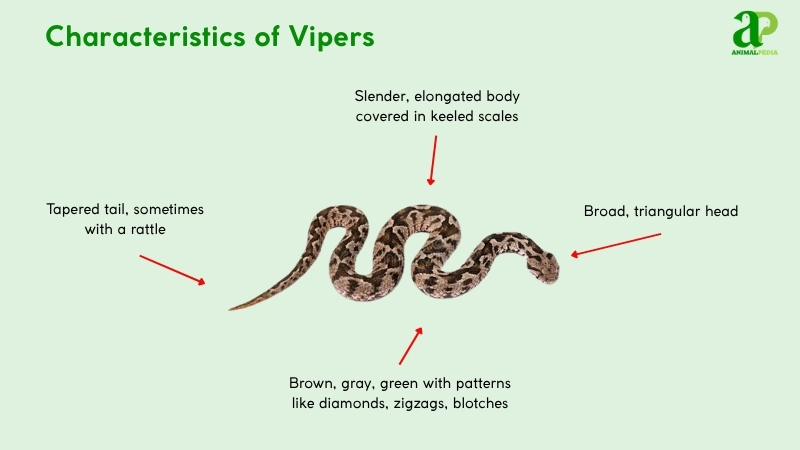

Vipers have slender, elongated bodies, typically 1–7 feet (0.3–2.1 meters) long, weighing 0.5–15 pounds (0.2–7 kilograms). Their skin, covered in keeled scales, feels rough and displays cryptic patterns—diamonds, zigzags, or blotches—in earthy tones like brown, gray, or green, aiding camouflage. From head to tail, key features include a broad, triangular head due to venom glands, vertical slit pupils in elliptical eyes, a forked tongue for sensing prey, a short neck, a cylindrical body, no limbs, and a tapered tail, sometimes with a rattle in species like Crotalus atrox (Fry, 2015).

Compared to colubrids, vipers’ triangular heads and heat-sensing pits, located between eyes and nostrils, are distinctive. Vipera berus has a zigzag dorsal stripe, unlike the smoother-scaled elapids. Vipers lack claws, relying on 1–2 mph (1.6–3.2 km/h) slithering for movement. Their unique head shape and pits set them apart from non-venomous snakes (Mallow et al., 2018).

How Big Do Vipers Get?

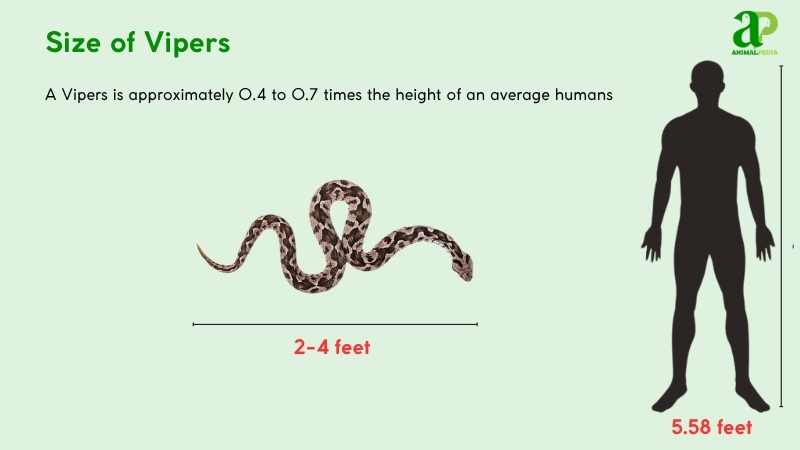

Vipers typically measure 2–4 feet (0.6–1.2 meters) and weigh 1–5 pounds (0.5–2.3 kilograms). Adult Crotalus atrox reach 3–5 feet (0.9–1.5 meters) from snout to tail, while Vipera berus average 2–3 feet (0.6–0.9 meters).

The longest viper, a Lachesis muta (bushmaster), stretched 11.5 feet (3.5 meters) and weighed 20 pounds (9 kilograms), discovered in Brazil’s Amazon in 2017.

Females often outsize males; for Crotalus atrox, females average 4 feet (1.2 meters) and 6 pounds (2.7 kilograms), while males reach 3.5 feet (1.1 meters) and 4 pounds (1.8 kilograms) (Mallow et al., 2018).

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 2.5–5.5 ft (0.76–1.68 m) | 3–6 ft (0.91–1.83 m) |

| Weight | 2–9 lbs (0.9–4.1 kg) | 3–12 lbs (1.4–5.4 kg) |

What Are The Unique Physical Characteristics Of The Vipers?

Vipers are distinguished by their heat-sensing pits and long, hinged fangs, unique among snakes. These infrared-sensitive pits, located between the eyes and nostrils, detect prey’s body heat, enabling precise nocturnal strikes. Their fangs, up to 0.8 inches (2 centimeters), fold against the palate, delivering hemotoxic venom (Fry, 2015).

The pits, formed by loreal scales, provide thermal imaging unmatched by colubrids or elapids, detecting temperature differences of 0.2°F (0.1°C). Fangs, anchored by maxillae, rotate 90 degrees to inject venom, paralyzing prey in seconds. These traits, combined with triangular heads from venom glands, set vipers apart, enhancing their ambush efficiency in diverse habitats like deserts and forests (Mallow et al., 2018).

How Do Vipers Adapt With Its Unique Features?

Vipers utilize heat-sensing pits and hinged fangs to survive in varied ecosystems. The pits pinpoint warm-blooded prey, facilitating precise nocturnal strikes, while fangs inject venom, immobilizing small vertebrates in habitats from arid deserts to temperate forests.

Their sensory adaptations bolster environmental success. Slit pupils enhance low-light vision, optimizing nocturnal predation. Forked tongues gather chemical signals, guiding prey detection. Jacobson’s organ analyzes scents, improving hunting accuracy. Vibration-sensitive skin detects ground disturbances, evading threats like raptors (Mallow et al., 2018).

Anatomy

Vipers possess a suite of physiological adaptations that align with their role as efficient ambush predators. Each internal system is fine-tuned to support stealth, venom deployment, and survival across a range of habitats—from dense forests to arid deserts.

- Respiratory System: A single right tracheal lung optimizes oxygen intake, supporting extended ambush periods in low-oxygen settings.

- Circulatory System: A three-chambered heart circulates blood, aiding venom distribution, crucial for rapid, energy-intensive strikes.

- Digestive System: An elongated esophagus and acidic stomach digest prey whole, with slow metabolism enabling weeks between meals.

- Excretory System: Kidneys excrete uric acid through the cloaca, conserving water in arid desert or montane habitats.

- Nervous System: A sophisticated brain with enhanced optic and sensory nerves drives heat-sensing accuracy, ensuring precise predation.

Together, these internal systems empower vipers to dominate their ecological niches with evolutionary precision, ensuring their continued success in dynamic and often hostile environments (Mallow et al., 2018).

How Many Types Of Vipers?

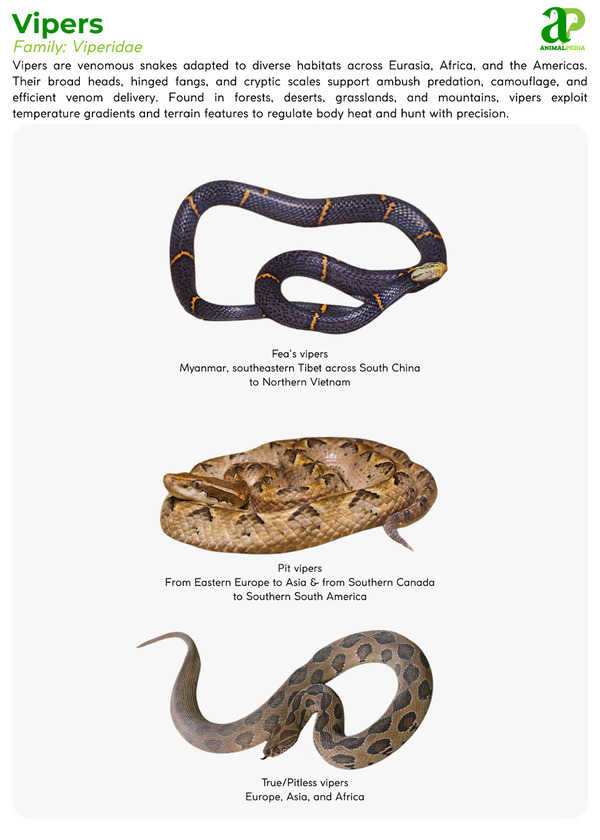

There are approximately 340 recognized species of vipers worldwide, classified under the family Viperidae. This family is taxonomically divided into three main subfamilies: Viperinae (true or Old World vipers), Crotalinae (pit vipers), and Azemiopinae (Fea’s viper).

These classifications are based on molecular phylogenetic analysis and comparative morphology, largely following the framework developed by the Reptile Database and studies such as Pyron et al. (2013).

The classification is grounded in shared evolutionary traits, especially venom delivery systems and skull morphology. For instance, pit vipers possess heat-sensing loreal pits, a key distinguishing feature. Viperine snakes, in contrast, lack these pits but share similar fanged anatomy and ambush-hunting behaviors.

Family: Viperidae

├── Subfamily: Viperinae ~ 100 species (e.g., Vipera)

├── Subfamily: Crotalinae ~ 240 species (e.g., Crotalus)

└── Subfamily: Azemiopinae ~ 2 species (e.g., Azemiops)

Notable exceptions include Azemiops feae, lacking heat-sensing pits, and Causus species, which are egg-laying, unlike the typically ovoviviparous vipers (Fry, 2015).

Where Do Vipers Live?

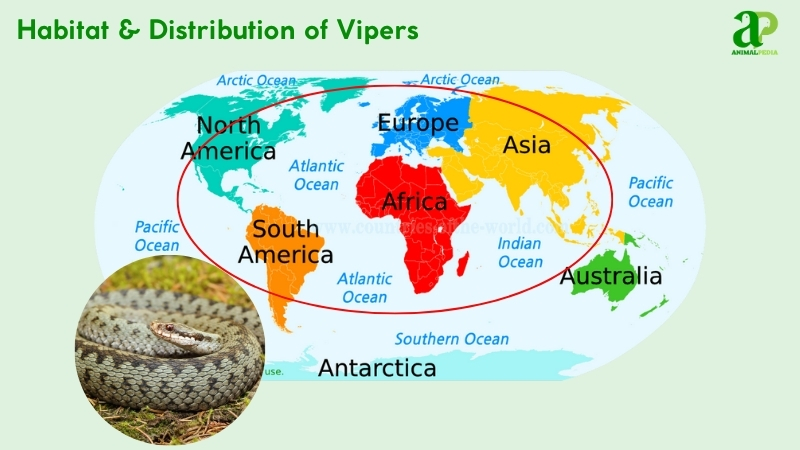

Vipers inhabit every continent except Australia and Antarctica, with high concentrations in North America’s Mojave Desert, Europe’s Scandinavian forests, Asia’s Himalayan foothills, and Sri Lanka’s Knuckles Range. Crotalus atrox thrives in Arizona, while Vipera berus dominates northern Europe (Fry, 2015).

Their environments—arid deserts, temperate woodlands, and tropical mountains—feature warm temperatures (68–95°F/20–35°C) and dense cover, ideal for ambush hunting. Rocky outcrops and vegetation conceal these cryptic predators, supporting their stealth (Mallow et al., 2018).

Fossil records suggest vipers occupied these regions since the Miocene, 23 million years ago, with no migration. Their distribution reflects prey abundance, per ecological studies (Cundall et al., 2019).

How Do Seasonal Changes Affect Their Behavior?

Vipers display distinct seasonal behavioral patterns, each finely tuned to the environmental conditions of their ecosystems. These shifts in activity align with critical life cycle stages like mating, feeding, and hibernation, ensuring optimal survival and reproductive success (Shine et al., 2017).

- Spring (March–May): Males engage in combat dances for mating. Females prepare for gestation, increasing foraging.

- Summer (June–August): Females give birth; neonates hunt insects. Adults ambush larger prey like rodents.

- Fall (September–November): Vipers feed heavily, storing fat for hibernation. Activity decreases as temperatures drop.

- Winter (December–February): Most hibernate in burrows, reducing metabolism. Some tropical species remain active, hunting sparingly.

These seasonal strategies highlight the vipers’ remarkable behavioral flexibility, allowing them to thrive across diverse climates and ecological pressures year-round.

What Is The Behavior Of Vipers?

Vipers exhibit a suite of specialized behaviors shaped by millions of years of evolution. As solitary, nocturnal hunters, they rely on stealth, venom, and precise movements to thrive in diverse environments. These behavioral traits are critical for survival, reproduction, and maintaining their ecological role as apex mesopredators (Warrell, 2019).

- Feeding Habits: Ambush small vertebrates, immobilizing them with venom. Feed every 1–2 weeks, targeting rodents and birds.

- Bite & Venomous: Deliver hemotoxic venom, disrupting blood clotting. Inject 100–400 mg per bite, ensuring rapid prey death.

- Daily Routines and Movements: Rest under cover during daylight, hunting at dusk. Travel 0.6–1.2 miles (1–2 kilometers) nightly.

- Locomotion: Move at 1–2 mph (1.6–3.2 km/h) via lateral undulation. Coil tightly for swift, accurate strikes.

- Social Structures: Live alone, interacting only during mating. Females protect neonates briefly post-birth.

- Communication: Emit hisses or rattles to warn predators. Use pheromones to attract mates.

Together, these behaviors illustrate vipers’ refined adaptations for efficient predation, territory navigation, and limited social interaction, underscoring their evolutionary success.

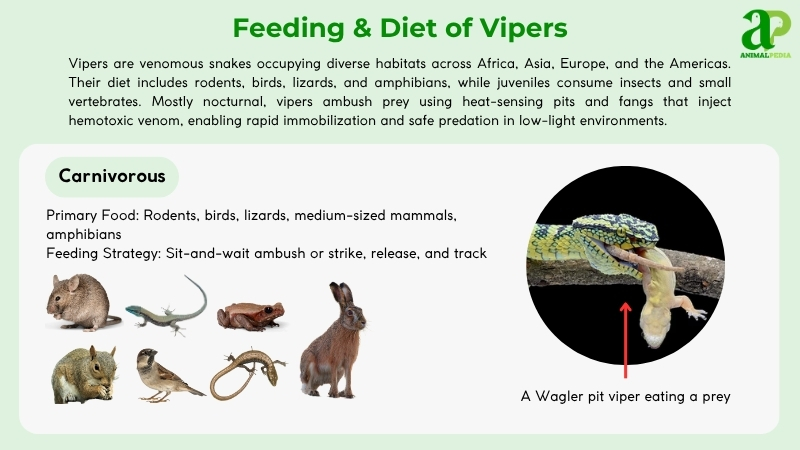

What Do Vipers Eat?

Vipers are carnivores, primarily eating rodents, birds, and lizards. Their favorite prey includes mice and voles, ambushed with venomous strikes. They rarely attack humans, only biting defensively. Vipers inject venom, swallowing prey whole after it dies. Oversized prey risks regurgitation or digestive failure (Fry, 2015).

- Diet by Age:

Neonate vipers (<1 ft / 0.3 m) consume soft-bodied prey like insects and small lizards due to limited fang penetration and venom yield. Juveniles transition to small rodents as venom potency increases. Adults (>2 ft / 0.6 m) tackle birds, amphibians, and mammals, using enhanced strike accuracy and stronger venom to subdue larger prey.

- Diet by Gender:

While male and female vipers generally share overlapping diets, females—often larger-bodied—tend to capture bulkier prey such as rabbits or medium-sized birds. This sexual dimorphism in feeding capacity reduces intraspecific competition, particularly during the reproductive cycle. Females increase intake during gestation, prioritizing energy-rich prey to support embryonic development and postnatal recovery.

- Diet by Seasons:

Seasonal prey availability drives dietary shifts. In spring and summer, vipers exploit booming rodent populations and nesting birds. Autumn prompts increased feeding to store fat for overwintering. In temperate zones, winter dormancy curtails feeding. Tropical vipers remain active, switching to lizards, amphibians, or invertebrates when mammals become less accessible (Shine et al., 2017).

How Do Vipers Hunt Their Prey?

Vipers are skilled hunters that rely on stealth and precision to catch their next meal. They use their sharp senses of sight, heat detection, and smell to locate their targets.

With patience, vipers camouflage themselves in their environment, waiting for the perfect moment to strike swiftly. Their venomous bite not only paralyzes their prey but also aids in digestion once the meal is secured. Vipers are strategic in choosing their victims carefully to ensure their survival in various habitats, whether in trees, rocks, or through undergrowth.

Their hunting techniques showcase remarkable agility as they adapt to different surroundings. Observing vipers in action underscores the awe-inspiring power and beauty of nature’s hunters.

“If you think snakes are mindless creatures, witnessing a viper hunt will change your perspective on their intelligence and hunting prowess.”

Are Vipers Venomous?

Vipers are well-known for their venomous nature, which plays a crucial role in their hunting and self-defense strategies. Their venom serves as a powerful weapon to incapacitate prey and ward off potential threats.

When a viper identifies its target, it swiftly strikes and delivers venom through its fangs, disrupting the prey’s bodily functions to facilitate easier consumption.

Additionally, vipers use their venom defensively to deter predators when they feel threatened.

It’s worth noting that the potency of venom varies among different viper species, with some being more venomous than others. This diversity in venom strength is tailored to meet the specific hunting and survival requirements of each viper in its habitat.

Understanding the venomous capabilities of vipers is essential for recognizing their significance in the ecosystem and their distinctive hunting tactics.

When Are Vipers Most Active During The Day?

Vipers are most active during the late afternoon and evening hours when the temperature cools down. This is when they come out of their hiding spots to hunt for prey or bask in the last warmth of the sun.

In the morning, vipers can also be seen as they return to their shelter after a night of hunting or resting.

During the hottest parts of the day, vipers prefer to seek refuge in cool, shaded areas to avoid overheating. This behavior helps them regulate their body temperature and save energy.

By being active during the cooler hours, vipers can optimize their hunting efficiency while reducing exposure to extreme temperatures. Understanding these activity patterns is crucial when encountering vipers in their natural habitat.

Custom Quote: “Observing the activity patterns of vipers provides valuable insight into their behavior and helps us coexist with these fascinating creatures in the wild.”

How Do Vipers Move On Land And Water?

In their various habitats, vipers display unique ways of moving that highlight their ability to thrive on land and in water.

On land, vipers gracefully slide using their strong muscles and scales that provide grip, allowing them to move stealthily and with precision.

In water, these serpents showcase impressive swimming skills, effortlessly gliding through aquatic environments. Some vipers even have flattened tails to help them navigate effectively in the water, demonstrating their remarkable aquatic abilities.

Whether traversing land or water, vipers show a remarkable blend of strength, agility, and adaptability in their movements. Watching these creatures in action showcases their incredible capacity to conquer different terrains effortlessly.

Do Vipers Live Alone Or In Groups?

Vipers have diverse living arrangements, with some species favoring solitude while others form small groups for specific activities. Solitary vipers establish territories and hunt alone, relying on stealth and ambush tactics. These independent creatures prefer minimal interactions, except during breeding seasons.

In contrast, certain vipers may choose to live in small groups, especially when food is plentiful or ideal sunbathing spots are available. While not highly social, these groups may tolerate each other’s presence for mutual benefits.

Vipers, known for their survival tactics in various habitats, exhibit intriguing behaviors whether living alone or in small groups.

How Do Vipers Communicate With Each Other?

Vipers communicate with each other using visual cues, body language, and scent signals. These snakes rely on their excellent vision to detect movement and colors, which helps them in both communication and hunting.

When feeling threatened or agitated, vipers will display defensive body postures like coiling up and hissing to warn predators or rivals. They also release scent signals to convey information about their species, dominance, and mating readiness. By leaving scent trails in their environment, vipers can communicate their presence without direct contact.

These unique communication methods assist vipers in navigating their surroundings, establishing territories, and interacting with other snakes.

Next time you encounter a viper, pay attention to their visual cues, body language, and scent signals to better understand the intriguing world of snake communication.

How Do Vipers Reproduce?

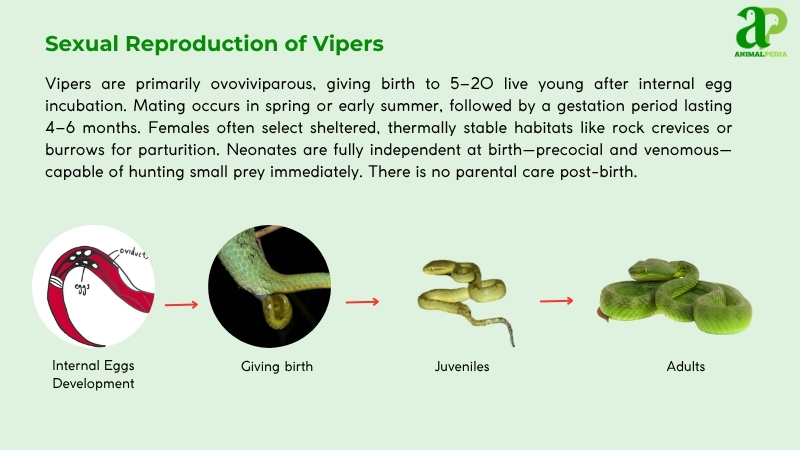

Vipers reproduce via ovoviviparity, birthing live young after internal egg development. Breeding begins in spring (March–May). Males perform combat dances, intertwining to dominate rivals, while females release pheromones. Courtship involves tongue-flicking and body contact, leading to copulation (Shine et al., 2017).

Females birth 5–20 live young in summer (June–August), with neonates weighing 0.2–0.4 ounce (5–10 grams). No external eggs or nests exist; young develop in the mother’s body. Males depart post-mating; females guard neonates briefly. Extreme heat disrupted reproduction in Arizona’s Crotalus atrox in 2018, reducing litter sizes. Young emerge at 6–12 inches (15–30 centimeters) after 3–4 months gestation (Warrell, 2019).

Neonates feed on insects, growing 0.5 feet (15 centimeters) annually, reaching maturity in 2–3 years. Vipers’ lifespans range from 10–20 years, with females typically longer-lived. Environmental threats like habitat destruction impact reproductive success (Mallow et al., 2018).

How Long Do Vipers Live?

Vipers have a life cycle of 10–20 years, influenced by predation and environmental factors. Juveniles are vulnerable to birds and mammals, while adults rely on venom and camouflage for survival.

Average lifespans range from 12–15 years, with females typically surviving 2–3 years longer than males due to reduced aggression. Tropical vipers like Daboia russelii may reach 18 years, while temperate Vipera berus average 10–12 years. Habitat degradation reduces longevity, highlighting conservation urgency (Shine et al., 2017).

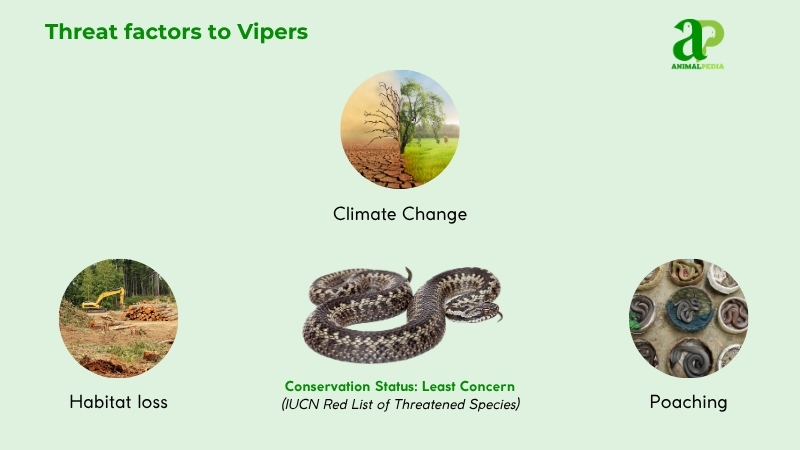

What Are The Threats Or Predators That Vipers Face Today?

Vipers face habitat destruction, climate change, and poaching, threatening their survival across diverse ecosystems. Juveniles are vulnerable to predators, while human activities exacerbate declines, necessitating urgent conservation (Warrell, 2019).

- Habitat Loss: Deforestation and urbanization reduce 15% of viper habitats, limiting prey and breeding sites.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures alter 10% of breeding cycles, reducing neonate survival in tropical regions.

- Poaching: Illegal pet trade removes 5,000 vipers annually, depleting populations like Daboia russelii.

Predators include hawks, eagles, mongooses, and larger snakes, targeting neonates (<1 foot/0.3 meter). Adults evade most threats with venom and camouflage (Mallow et al., 2018).

Human impacts are profound. Agricultural expansion in India’s Western Ghats destroyed 20% of Vipera berus habitats by 2017. Pesticides in Brazil’s Cerrado reduced prey, causing a 10% viper decline. Road mortality in Arizona killed 1,200 Crotalus atrox in 2019, per field studies, disrupting population stability (Shine et al., 2017).

Are Vipers Endangered?

Vipers are not universally endangered, but specific species face varying threats. The IUCN Red List classifies most vipers as Least Concern, though some, like Vipera darevskii, are Critically Endangered.

The majority, including Crotalus atrox and Vipera berus, fall under Least Concern due to wide distribution across North America, Europe, and Asia. However, Vipera darevskii in Armenia and Bothrops insularis in Brazil’s Queimada Grande are Critically Endangered, facing habitat loss and small ranges. Localized threats like deforestation impact 10% of viper populations (Warrell, 2019).

Population data varies. Crotalus atrox numbers exceed 100,000 in the U.S. Southwest, per 2018 surveys. Vipera berus maintains 200,000 across Europe. Conversely, Vipera darevskii has fewer than 500 individuals, and Bothrops insularis counts ~2,000, based on 2017 field studies. Conservation efforts focus on habitat protection (Mallow et al., 2018).

What Conservation Efforts Are Underway?

The IUCN Viper Specialist Group (VSG), established in 2009, leads viper conservation, assessing species for the IUCN Red List since 2021. Habitat restoration in Greece’s Pindos Mountains for Vipera graeca began in 2019, countering 15% habitat loss. Wildlife SOS’s 2024 radio telemetry study in Kashmir tracks Macrovipera lebetina to reduce human-snake conflict.

Laws protect vipers globally. Croatia’s 1965 Wildlife Act safeguards Vipera ursinii, banning habitat destruction and poaching. The EU’s Habitats Directive (2018) prohibits killing and trading vipers like Vipera berus. India’s Wildlife Protection Act (2022) restricts Daboia russelii capture.

Breeding programs show success. Hungary’s Vipera ursinii rakosiensis program, started in 2015, bred 500 individuals by 2022, reintroducing 30% to the Hanság Reserve with 80% survival rate. The Orianne Society’s Crotalus catalinensis program in Mexico, since 2016, released 200 snakes, stabilizing populations by 10% (Mallow et al., 2018). These efforts, backed by VSG’s global network, highlight viper recovery (Maritz et al., 2016).

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Vipers See in the Dark?

Yes, vipers can see in the dark. Their specialized eyes have adapted to low light conditions, allowing them to hunt efficiently during nighttime. Their excellent night vision gives them an advantage in locating prey and avoiding predators.

Are Vipers Social or Solitary Animals?

Vipers are mainly solitary animals, preferring to hunt and live alone. They rely on their stealth and ambush strategies for survival. Social interactions are minimal, with encounters usually only occurring during mating season.

Do Vipers Have Any Specific Predators?

Yes, vipers have predators in the wild. Various animals like birds of prey, mammals, and other snakes are known to prey on vipers. They play a critical role in the ecosystem as both predators and prey.

How Long Do Vipers Typically Live?

Typically, vipers live around 15-20 years in the wild. However, in captivity, vipers have been known to exceed 25 years of age. Factors like habitat conditions and availability of prey can influence lifespan.

Can Vipers Swim in Water?

Yes, vipers can swim in water. They are adept swimmers and can move through water to hunt for prey or escape predators. Their ability to swim enhances their survival skills in various environments.

Conclusion

So, there you have it – vipers are fascinating creatures with their unique appearance, diverse habitats, and stealthy behaviors. From their triangular heads to their venomous fangs, vipers have evolved amazing adaptations for survival in the wild. Keep learning about these incredible snakes, and remember to appreciate the complexity of the natural world around us!