Water moccasin snakes (Agkistrodon piscivorus) form a single venomous species in the viper family. Also called cottonmouths, these powerful reptiles dominate the wetlands of the southeastern United States. They reach over 4 feet long with thick, muscular bodies marked by distinctive dark bands.

Their hallmark defense—a wide-open, cotton-white mouth—serves as a clear warning to potential threats. These snakes inhabit diverse aquatic ecosystems, from coastal marshlands to inland swamps, including specific habitats such as Dauphin Island off Alabama’s coast.

As apex predators, cottonmouths hunt with deadly efficiency. They employ ambush tactics, striking prey with hemotoxic venom that breaks down tissue. Their varied diet—fish, frogs, rodents, and birds—demonstrates ecological adaptability. Though rarely aggressive toward humans, their defensive bite requires immediate medical attention.

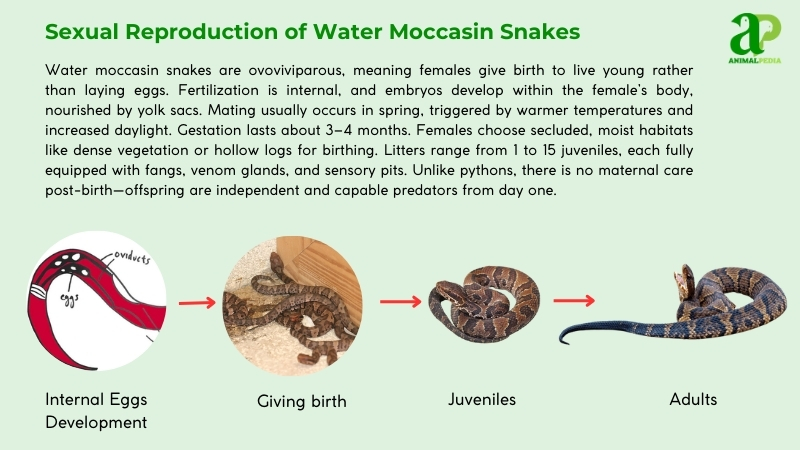

Breeding occurs primarily in spring. Female cottonmouths bear live young (viviparity) rather than laying eggs, typically producing 6-8 offspring after three months’ gestation. These neonates emerge fully equipped with venom and hunting instincts. Their rapid growth leads to sexual maturity within 2-3 years, with wild specimens typically surviving 15-20 years.

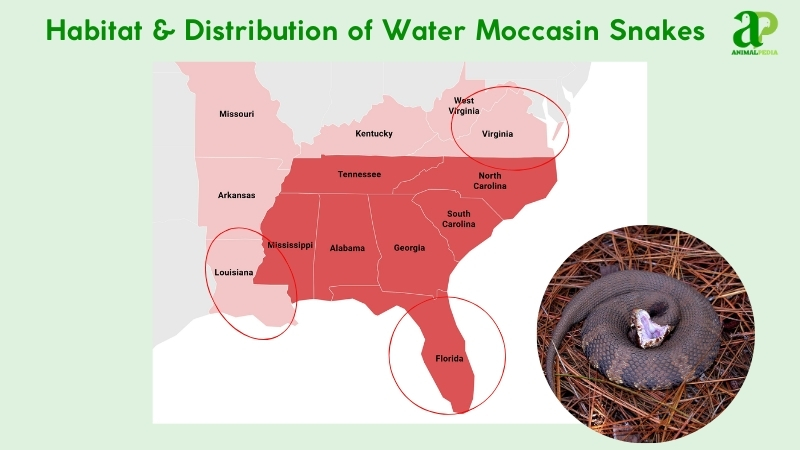

Their habitat preference ties them firmly to water bodies throughout their range. From Florida’s Everglades to Virginia’s Great Dismal Swamp, these serpents thrive in warm, humid environments where they play crucial roles in wetland food webs and population control.

This guide explores the cottonmouth’s biology, distribution, and behavior—offering insight into this often misunderstood yet ecologically vital pit viper.

What Do The Water Moccasin Snakes Look Like?

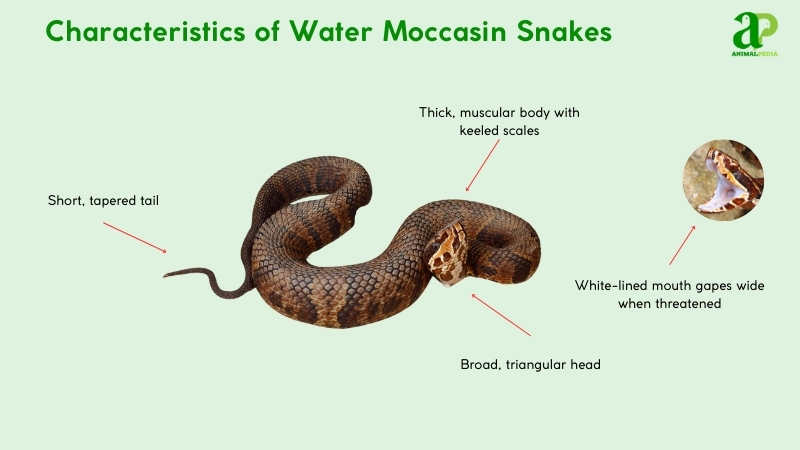

Water moccasins (Agkistrodon piscivorus) have thick, muscular bodies that often reach over 4 feet in length. Their color ranges from dark brown to almost black, with subtle crossbands that become less visible as they age. Young water moccasins display bolder patterns. Their keeled scales feel rough to the touch, an adaptation that helps them navigate aquatic environments. These powerful pit vipers are built for stealthy movement through swamps and wetlands.

The snake’s triangular head contains specialized pit organs for heat detection, positioned between the eyes and nostrils. These organs help them locate prey even in darkness. Small, intense eyes sit above a forked tongue that constantly samples the air for chemical information. A stocky neck connects to their heavy body, which tapers to a relatively short tail. Their scales have a non-reflective finish that aids in camouflage.

When threatened, water moccasins display their most famous feature—a gaping white mouth that sharply contrasts with their dark exterior, earning them the name “cottonmouth.” Unlike the related copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix), water moccasins are stockier and prefer aquatic habitats, while copperheads are slimmer and primarily terrestrial.

“While the Water Moccasin mastered the wetlands, an entirely different group of pit vipers evolved to conquer the opposite extreme: the desert. Meet the masters of the arid Southwest: Western Rattlesnakes

How Big Do Water Moccasin Snakes Get?

Water moccasins average 2 to 4 feet (0.6 to 1.2 meters) in length and weigh 3 to 10 pounds (1.4 to 4.5 kilograms). Adults typically reach 3.5 feet (1.1 meters) from snout to tail.

The longest recorded cottonmouth stretched 6.1 feet (1.85 meters), found in Virginia’s Dismal Swamp, per Gibbons and Dorcas (2015). This hefty specimen weighed nearly 15 pounds (6.8 kilograms).

Males often outsize females slightly. Males average 3.8 feet (1.15 meters) and 8 pounds (3.6 kilograms), while females hit 3.2 feet (0.98 meters) and 6 pounds (2.7 kilograms). Here’s a table:

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 3.5-6 ft (1.06–1.83 m) | 2.5-3.2 ft (0.76–0.97 m) |

| Weight | 3.5–8 lbs (1.6–3.6 kg) | 2–6 lbs (0.9–2.7 kg) |

What Are The Unique Physical Characteristics Of The Species?

The water moccasin, or cottonmouth, is unmistakable for its bright white mouth. When threatened, it coils and opens wide, showing the cotton-white lining that no other North American viper displays. This warning, combined with its triangular head and heat-sensing pits, makes it instantly recognizable. These robust reptiles often grow beyond 4 feet in length, with bodies built for life in water.

How Do Water Moccasin Snakes Sense Their Environment With Their Unique Features?

The water moccasin’s pit organs—heat-sensing marvels—let it thrive in the wild. These infrared detectors, nestled between the eyes and nostrils, pinpoint prey in dark, murky waters, ensuring survival as an ambush predator.

This unique feature pairs with sharp senses. Keen eyesight spots movement, aiding stealthy hunts. A flickering, forked tongue gathers chemical cues, mapping its swampy terrain. Sensitive skin feels vibrations, alerting it to threats or prey. Together, these traits—detailed in Gibbons and Dorcas (2015)—forge a master of wetland adaptation.

Anatomy

The water moccasin boasts a finely tuned anatomy that enables it to thrive in its semi-aquatic, swampy environments. Each system in its body is adapted for efficient hunting, survival, and reproduction in wetland ecosystems of the southeastern United States.

- Respiratory System: Paired lungs, with the right lung elongated, pull oxygen from humid air or water surfaces. This aids survival in swampy habitats (Gibbons & Dorcas, 2015).

- Circulatory System: A three-chambered heart pumps blood efficiently. Venom production is tied to its robust vascular network, supporting predatory life.

- Digestive System: A short, muscular gut breaks down prey—fish and mammals—quickly. Its stomach handles whole meals, optimizing energy in wetlands.

- Excretory System: Kidneys filter waste into uric acid, conserving water. This suits its semi-aquatic, warm environment with minimal loss.

- Nervous System: A keen brain and spinal cord link to the pit organs and eyes. This setup sharpens its heat-sensing and hunting precision.

Together, these physiological systems make the water moccasin a formidable predator. Its internal adaptations mirror its external stealth, enabling it to dominate wetland food webs with evolutionary precision.

Where Do Water Moccasin Snakes Live?

Water moccasins inhabit the southeastern United States. They thrive in Florida’s Everglades, Louisiana’s bayous, and Virginia’s Dismal Swamp—wetlands teeming with water and prey. Coastal plains and islands like Dauphin Island, Alabama, support substantial populations of these venomous pit vipers.

How Do Seasonal Changes Affect Their Behavior?

Water moccasins display strong seasonal rhythms influenced by temperature, humidity, and prey availability across their wetland habitats. Their semi-aquatic behavior tracks the climatic cycles of the southeastern United States.

These snakes adjust activity patterns across two primary seasons: warm (spring/summer) and cold (fall/winter). Behavioral changes are driven by thermoregulation needs and ecological cues.

- Warm Season (March–September): Activity surges. Snakes bask more, hunt actively for fish and amphibians, and mate. Shallow wetlands provide ample prey and ideal breeding grounds.

- Cold Season (October–February): As temperatures drop, moccasins reduce surface activity. They brumate in sheltered logs, burrows, or rock crevices, conserving energy and minimizing exposure.

These seasonal adaptations optimize their metabolic efficiency and reproductive timing, ensuring survival in dynamic wetland ecosystems.

What Is The Behavior Of Water Moccasin Snakes?

Water moccasins stand out as apex predators in North American wetlands. Their behaviors reflect a mastery of both aquatic and terrestrial environments, finely honed for survival and dominance in their ecological niche.

- Feeding Habits: They ambush fish, frogs, and small mammals. Diet flexibility aids their apex role.

- Bite & Venomous: Bites defend, not hunt. Hemotoxic venom subdues threats fast (Ernst & Ernst, 2011).

- Daily Routines: Night hunters, they bask by day. Seasonal shifts tweak this rhythm.

- Locomotion: Strong swimmers, they glide through water. On land, they coil and strike.

- Social Structures: Mostly solitary, save for mating. Males spar in spring.

- Communication: Gaping mouths warn foes. Vibrations signal presence.

Each behavior—whether in feeding, defense, or communication—highlights their evolutionary success. To truly understand their ecological role, one must first examine their behavior through the lens of adaptation.

What Do Water Moccasin Snakes Eat?

Water moccasin snakes are opportunistic carnivores that specialize in aquatic and semi-aquatic prey. Their diet and feeding behaviors shift with age, body size, reproductive cycles, and seasonal prey availability. As pit vipers, they rely on heat-sensing pits and venom to subdue prey efficiently in wetland ecosystems.

- Diet by Age

Juvenile water moccasins typically prey on small fish, tadpoles, and insects. These prey types are abundant and manageable in shallow water or along the banks. As they grow, adults expand their diet to include amphibians, birds, small mammals, and even other snakes. Their venom and flexible jaw structure allow them to capture and consume larger prey whole.

- Diet by Gender

Both male and female moccasins share similar dietary preferences. However, during the breeding season, males may exhibit heightened foraging behavior due to increased energy demands. There is no documented difference in prey type between sexes.

- Diet by Seasons

During the wet season (spring to late summer), water levels rise and aquatic prey becomes abundant. Water moccasins hunt more actively during this time. In the dry season (fall and winter), prey activity slows, and moccasins reduce their feeding frequency, relying on fat reserves and moving less frequently (Winne et al., 2020).

How Do Water Moccasin Snakes Hunt Their Prey?

Water Moccasin snakes (Agkistrodon piscivorus) hunt through a perfected ambush strategy. Their dark coloration creates effective camouflage in wetland habitats, rendering them nearly invisible to potential prey. These cottonmouths position themselves strategically near aquatic environments where prey animals gather.

They strike with precision when prey approaches. The pit viper’s attack happens in a fraction of a second, delivering hemotoxic venom through hollow fangs. Their exceptional swimming capabilities enable silent movement through water, increasing predation success on fish, amphibians, and small mammals.

The venom compounds serve dual purposes: immobilizing prey and initiating external digestion. This biochemical adaptation breaks down tissue before it is consumed. Through their specialized hunting techniques, Water Moccasins maintain ecological balance in riparian ecosystems throughout the southeastern United States, controlling populations of various prey species while serving as indicators of wetland health.

Are Water Moccasin Snakes Venomous?

Water Moccasin Snakes, also called Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus), are highly venomous pit vipers. Their potent hemotoxic venom breaks down blood cells and tissue. When threatened, these snakes display their signature defense: opening their mouths wide to reveal the stark white interior, which gives them their common name.

These reptiles aren’t typically aggressive without provocation, but will defend themselves when cornered. Their venom delivery system is highly efficient, injecting toxins that can cause severe tissue damage, intense pain, and potentially life-threatening complications if left untreated. A Cottonmouth bite requires immediate medical intervention and antivenom treatment.

In their native southeastern United States wetland habitats, Water Moccasins serve as important apex predators. They help maintain ecological balance by controlling populations of rodents, frogs, and fish. Despite their dangerous reputation, these snakes prefer to avoid human contact when possible.

If you encounter a Water Moccasin in the wild, maintain a safe distance of at least six feet. Never attempt to handle or provoke these powerful, venomous serpents. Respect their space and role in the ecosystem.

When Are Water Moccasin Snakes Most Active During The Day?

Water Moccasin Snakes are most active during the warmer parts of the day, particularly in the early morning and late afternoon. These snakes enjoy soaking up the sun to regulate their body temperature, so you’re likely to spot them moving around more during these times.

They tend to avoid the intense midday heat by staying hidden and conserving energy until temperatures cool down. Despite their predictable routine, Water Moccasins are agile hunters, always prepared to strike when the opportunity arises.

If you find yourself near their habitats during these active periods, stay vigilant for any signs of these intriguing creatures. While Water Moccasins prefer certain times of the day, they’re efficient predators capable of swift strikes when hunting.

It’s important to observe them from a safe distance and appreciate their natural behaviors. By being aware of their activity patterns, you can enhance your understanding and respect for these stealthy reptiles.

How Do Water Moccasin Snakes Move On Land And Water?

Water moccasins move with distinct techniques across different environments. On land, these venomous pit vipers use lateral undulation—pushing against ground objects with their scales to propel forward. Their muscular bodies create S-shaped patterns as they navigate through underbrush, mud, and forest floors.

In aquatic habitats, water moccasins (also called cottonmouths) swim with impressive efficiency. They hold their heads above water while their bodies are partially submerged. Their laterally compressed tails function as effective paddles, allowing them to maneuver through swamps, marshes, and streams with minimal effort.

These semi-aquatic reptiles can seamlessly switch between terrestrial and aquatic locomotion. When threatened in water, they can either dive below the surface or display their famous defensive posture—mouth open wide, showing the white interior that gives them their cottonmouth name.

Their ability to thrive in wetland ecosystems showcases their evolutionary adaptations to the southeastern United States, where they hunt fish, amphibians, and small mammals across land-water boundaries.

Do Water Moccasin Snakes Live Alone Or In Groups?

Water Moccasin Snakes prefer a solitary lifestyle, living alone rather than in groups or packs. These snakes wander through their marshy habitats on their own, searching for food and shelter. By living independently, they have the freedom to move around without the constraints of group dynamics.

Living alone allows Water Moccasin Snakes to focus on their own survival without relying on others. They’re skilled hunters, capable of catching prey by themselves without needing help from other snakes.

This solitary existence also enables them to mark their territory and explore their surroundings without interference.

In essence, Water Moccasin Snakes thrive in their solitary way of life, navigating their marshy homes independently and showcasing their prowess as efficient hunters in the wild.

How Do Water Moccasin Snakes Communicate With Each Other?

Water Moccasin snakes, also known as Agkistrodon piscivorus, communicate through two primary channels: body language and chemical signals.

During interactions, these venomous pit vipers use distinct physical gestures, including head bobbing, body coiling, and tongue flicking, to transmit messages. An aggressive Water Moccasin will elevate its head and flatten its body as a warning display, while a non-threatened snake maintains fluid, calm movements.

Pheromones serve as crucial chemical messengers carrying vital information about species identification, sex determination, and reproductive readiness. By detecting these olfactory cues through their vomeronasal organ, Water Moccasins identify potential mates or rivals in their habitat.

This sophisticated communication system helps the cottonmouth establish territorial boundaries, locate breeding partners during mating season, and maintain social hierarchies within snake populations.

The interpretation of these serpentine signals provides researchers with valuable insight into the complex social dynamics of these semiaquatic reptiles in their natural wetland environments.

How Do Water Moccasin Snakes Reproduce?

Water moccasins reproduce viviparously—giving live birth instead of laying eggs. Females carry developing embryos internally, a characteristic trait of pit vipers (Crotalinae subfamily).

Breeding season begins in spring, typically March to May. Males become restless, tracking females through chemical pheromone trails. Courtship involves direct body contact, rubbing, and tongue flicks that analyze scent particles. Male combat often occurs—rivals wrestle by intertwining bodies, attempting to pin each other down to win mating rights. Copulation follows, lasting briefly but requiring precise alignment.

After mating, females enter a gestation period lasting roughly 3 months. They give birth to 6 to 8 live young (neonates) in late summer. Each baby snake weighs approximately 0.5 ounces (14 grams). Unlike egg-layers, water moccasins require no nest—births occur in microhabitats like hollow logs or abandoned burrows. Mothers guard offspring briefly; males provide no parental care. Environmental factors like drought or stress can disrupt reproductive cycles, as documented in field studies (Gibbons & Dorcas, 2015).

Newborns emerge fully equipped with functional venom glands and independence. They grow rapidly, reaching sexual maturity within 2 to 3 years. The average lifespan in the wild is 15 to 20 years. Importantly, females may skip reproductive years between broods, a strategy that conserves energy resources.

To learn more about the different types of squamata and their distinct features, check out our detailed section on this topic.

How Long Do Water Moccasin Snakes Live?

What Are The Threats Or Predators That Water Moccasin Snakes Face Today?

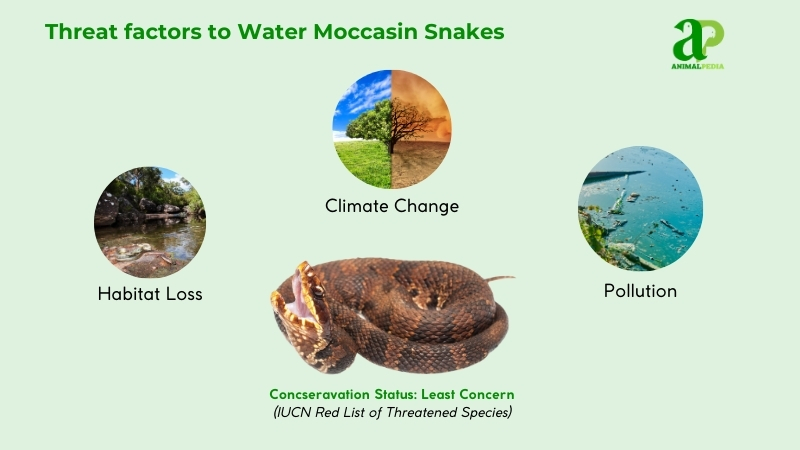

Water moccasins face habitat loss, pollution, and climate change. Predators and human actions add pressure. These threats hit hard in their southeastern U.S. range.

- Habitat Loss: Wetland drainage for agriculture slashes territory. Populations shrink as swamps vanish (Gibbons & Dorcas, 2015).

- Pollution: Runoff with pesticides weakens immunity. Prey dwindles, starving snakes.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures alter breeding. Floods or droughts disrupt nests, cutting survival rates.

Predators include alligators, hawks, and larger snakes, such as kingsnakes. Young cottonmouths fall prey most. Alligators dominate in swamps, snapping up adults during clashes. Hawks swoop on juveniles basking. Kingsnakes, immune to venom, constrict them.

Humans hit hardest. Roadkills spike near wetlands—thousands die yearly. Fear drives killings; venom myths fuel it. Wetland development buries habitats under concrete. Gibbons and Dorcas (2015) documented a 20% decline since 2000, attributing it to sprawl and persecution. Conservation lags, but awareness could curb this.

Are Water Moccasin Snakes Endangered?

Water moccasins aren’t endangered. These venomous pit vipers thrive across the southeastern United States, showing resilience despite human encroachment and habitat pressures.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies the water moccasin (Agkistrodon piscivorus) as “Least Concern.” This conservation status reflects their stable populations, high adaptability to various wetland ecosystems, and absence of immediate extinction risk. The 2012 assessment is valid with current population data. Their broad geographic distribution—spanning from Florida’s Everglades through coastal plains to Virginia’s cypress swamps—strengthens this classification.

Precise population figures are elusive; accurate census counts are challenging for researchers. Herpetologists Gibbons and Dorcas (2015) estimate that tens of thousands of cottonmouths exist, based on density surveys in prime habitats such as Louisiana bayous and Florida wetlands. While localized declines—up to 20% in urbanized watersheds—correlate with wetland destruction, overall population numbers are robust. No significant population crash indicates endangerment status. These riparian predators are common, not rare, throughout their native range.

What Conservation Efforts Are Underway?

Water moccasins benefit from targeted conservation efforts across their range. The Nature Conservancy has protected crucial wetlands in the Southeast U.S. since 2015. Their work spans vital swamps from Florida to Virginia, directly countering habitat fragmentation and loss.

Legal protection reinforces these efforts. While the Endangered Species Act (1973) doesn’t specifically list cottonmouths, it protects their ecosystems by protecting cohabiting listed species. State regulations, such as Missouri’s Wildlife Code (2016), explicitly prohibit killing these pit vipers, making such actions a misdemeanor. The federal Clean Water Act imposes strict limits on wetland drainage and pollution.

No formal captive breeding programs exist for cottonmouths—their viviparous reproduction complicates captive breeding. However, habitat restoration initiatives by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service naturally boost wild populations. In Dismal Swamp, conservation work since 2018 has reversed a 20% range decline documented by Gibbons & Dorcas (2015). The John E. Williams Preserve shows promising results with similar species, suggesting parallel recovery of cottonmouths.

Population metrics are limited, but stability appears consistent. The IUCN’s “Least Concern” classification (2012) continues to apply. Key stakeholders—TNC and USFWS—drive these conservation initiatives, while state-level protections demonstrate regional commitment. Together, these measures create a safety net for these often misunderstood riparian predators.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are water moccasins called cottonmouths?

Water moccasins are called cottonmouths due to the white, cotton-like lining of their mouths, which they display prominently when threatened, creating a striking visual warning to predators.

Can water moccasins climb trees?

Yes, water moccasins can climb low trees or bushes, often resting on branches over water to bask or hunt for birds, frogs, or small mammals that venture close.

How do water moccasins behave in winter?

In winter, water moccasins brumate in sheltered areas, such as burrows or under logs. They become less active, conserving energy, but may emerge on warm days to bask.

Can water moccasins live in saltwater?

Water moccasins prefer freshwater habitats but can tolerate brackish water in coastal marshes. They cannot survive in fully saltwater environments because they require fresh water.

How do water moccasins adapt to floods?

Water moccasins are well-adapted to floods, swimming to higher ground or floating on debris. Their semi-aquatic nature allows them to thrive in dynamic, waterlogged environments like swamps.

Do water moccasins travel far from water?

Water moccasins rarely stray far from water, preferring wetlands. They may venture onto dry land to bask or find mates but typically stay within a few hundred feet of aquatic habitats.

How do water moccasins sense their environment?

Water moccasins use heat-sensing facial pits to detect warm-blooded prey, keen eyesight for movement, and a forked tongue to collect chemical cues, aiding navigation and hunting in murky waters.

Can water moccasins coexist with other snakes?

Water moccasins often share habitats with non-venomous water snakes but may eat smaller snakes. They tolerate others unless competing for food or territory, occasionally displaying aggressive posturing.

How do water moccasins survive droughts?

During droughts, water moccasins seek water sources or burrow in moist soil. They reduce activity to conserve energy, relying on stored fat until conditions improve.

Can water moccasins be kept as pets?

Water moccasins are not recommended as pets due to their venomous nature and aggressive temperament. Handling requires expertise, and captivity is regulated to ensure safety and legality.

Conclusion

Water Moccasin Snakes are creatures with distinctive features, specialized habitat requirements, and significant ecological roles. Their dark, keeled scales and triangular heads make them instantly recognizable in southeastern wetlands. These venomous pit vipers demonstrate exceptional aquatic adaptations, including the ability to swim with their bodies partially submerged while keeping their heads above water.

Cottonmouths, as they’re also known, maintain ecosystem balance by controlling populations of rodents, amphibians, and fish. Their presence in swamps, marshes, and cypress stands indicates healthy wetland ecosystems. Despite their intimidating reputation, these semiaquatic reptiles primarily use their venom defensively rather than aggressively.

Understanding the Agkistrodon piscivorus enhances our appreciation for wetland biodiversity and the complex relationships within these habitats. By respecting these apex predators and their territories, we help preserve both the species and the vital ecosystems they inhabit.