Testudines (turtles and tortoises) are cold-blooded vertebrates in the class Reptilia. Their most distinctive feature is their shell, which consists of a domed carapace (upper shell) and a flattened plastron (lower shell), fused by bridges on each side. This protective structure is primarily composed of modified bony plates that fuse with the ribs and, in most species, is covered by keratin scutes.

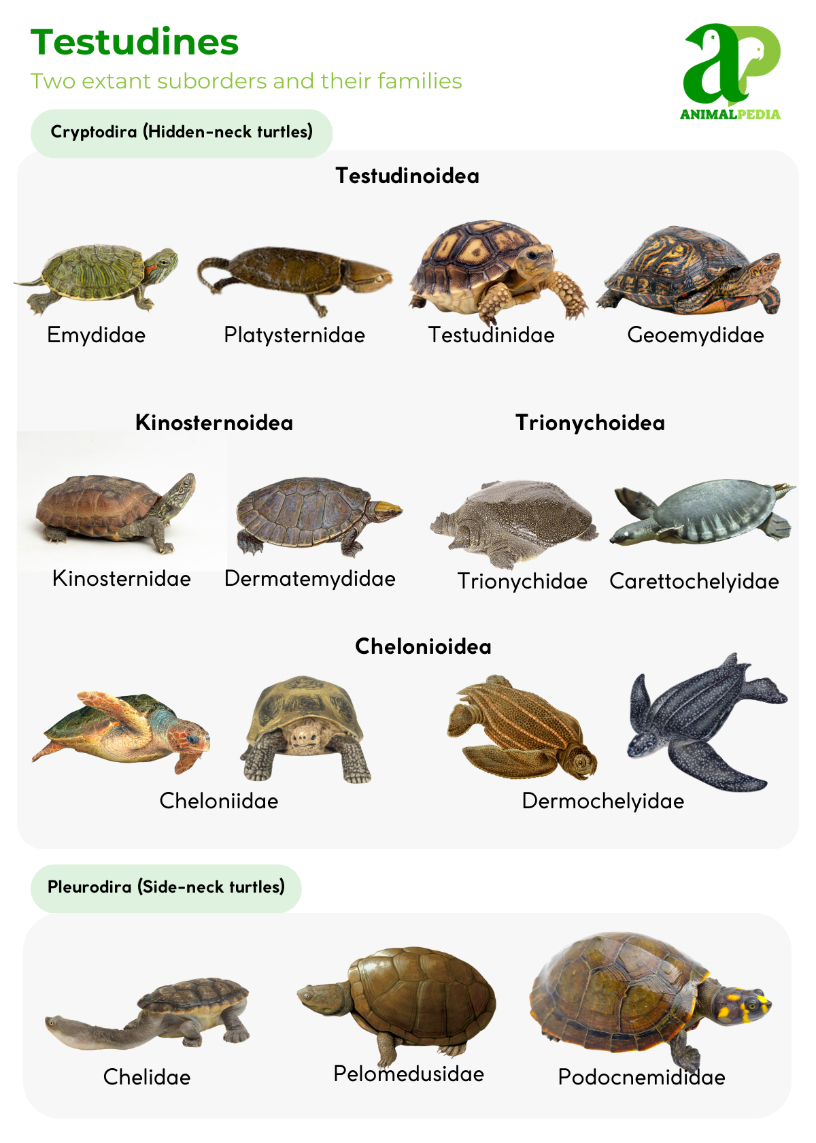

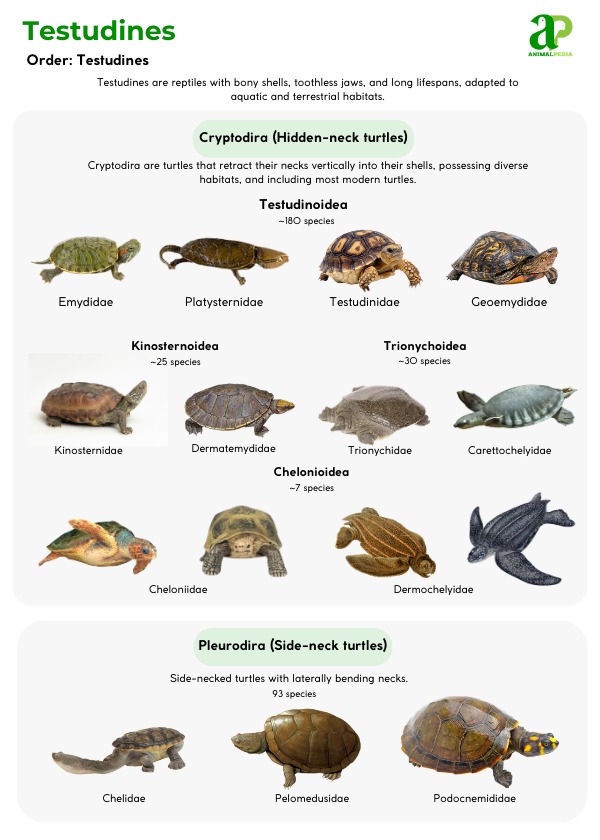

Modern Testudines are divided into two major suborders, the Cryptodira (hidden-necked turtles) and Pleurodira (side-necked turtles), which differ in how they retract their heads into their shells. There are approximately 360 living species of Testudines, ranging from fully terrestrial tortoises to freshwater terrapins and marine turtles. They are found across every continent except Antarctica, in diverse habitats from deserts and tropical forests to oceans.

Their feeding habits vary widely, from strict herbivores to opportunistic omnivores and specialized carnivores. While most species make relatively short seasonal movements, some marine turtles undertake long-distance migrations, traveling thousands of kilometers between feeding grounds and nesting beaches. Like other reptiles, they are air-breathing and lay amniotic eggs on land, although many species spend most of their lives in aquatic environments.

Testudines have been of significant cultural importance throughout human history, featuring prominently in mythology, art, and traditional practices worldwide. Many species, particularly small freshwater turtles and tortoises, are kept as pets.

However, these ancient reptiles face numerous contemporary threats, including habitat loss, collection for food and traditional medicine, plastic pollution, and accidental capture in fishing gear. Climate change poses an additional challenge, as egg incubation temperatures determine the sex of hatchlings in many species.

In the following sections, we’ll explore the intricate details of Testudines’ characteristics, classification, behaviors, adaptation, and crucial roles in maintaining healthy ecosystems.

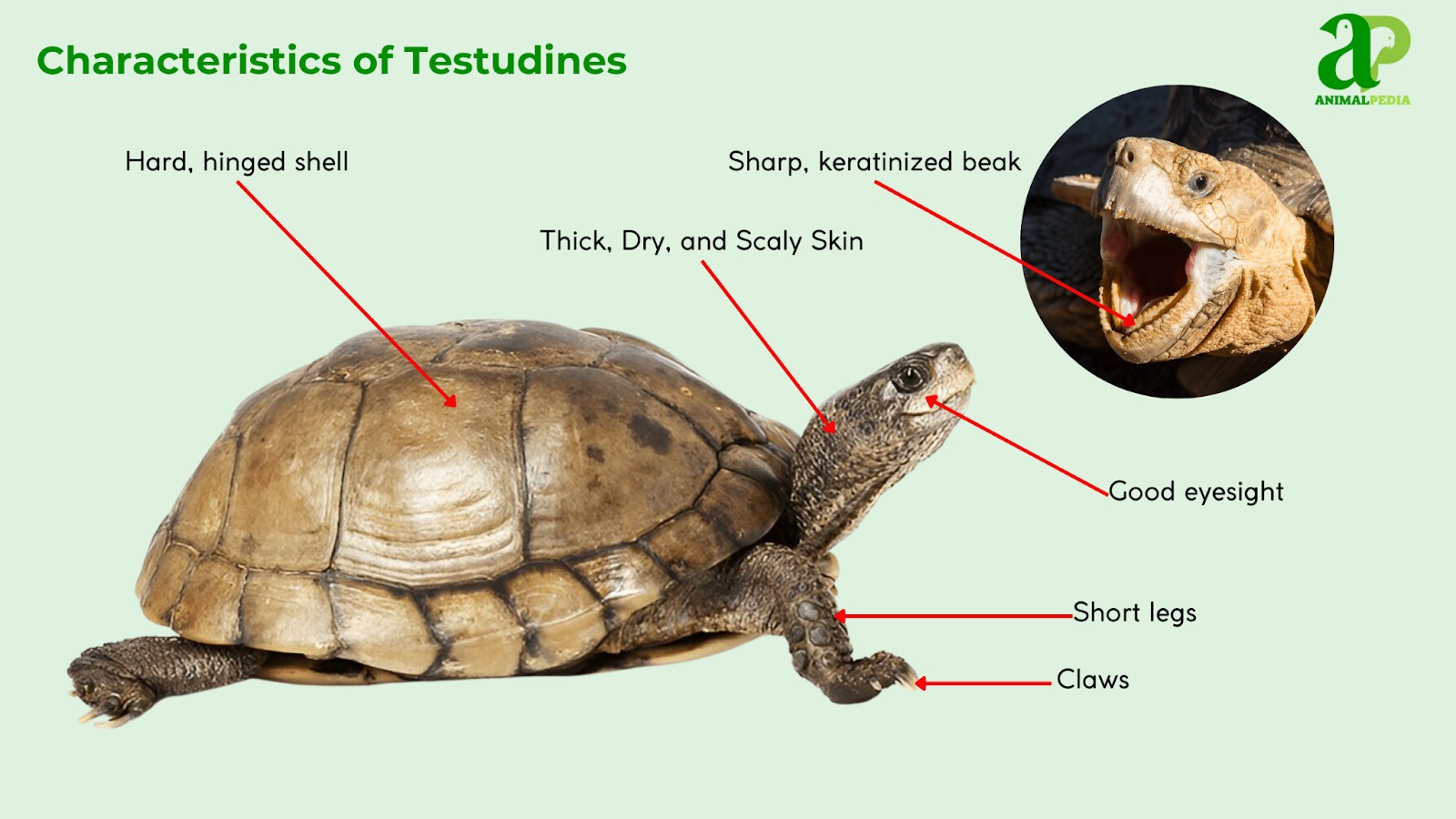

What are Testudines’ characteristics?

Testudines have outstanding features as follows

- 3,.9 to 10 inches (0,01 to 2,7 centimeters) in length and 0,38 to 1,100 pounds (200 and 1,000 grams) in weight.

- The turtle shell, with 50–60 fused bones, forms as ribs grow sideways into the carapacial ridge.

- Turtles have solid skulls, keratinous beaks, and flexible necks, which help them defend and feed.

Before exploring their unique features, let’s first look at the size range of Testudines, which varies greatly across species.

Size

The average size of Testudines varies widely, ranging from 3.9 to 10 inches (0.01 to 2.7 cm) in length and weighing between 0.38 to 1,100 pounds (200 to 1,000 grams).

The leatherback turtle is the largest living turtle species and the fourth-largest reptile, reaching over 8 feet 10 inches (2.7 meters) in length and weighing more than 1,100 pounds (500 kilograms).

In contrast, the smallest living turtle, Chersobius signatus from South Africa, measures no more than 3.9 inches (10 centimeters) in length and weighs only 6.1 ounces (172 grams).

The Shell

The shell is a unique structure among vertebrates, primarily serving as protection and a shield against environmental hazards.

Comprising between 50 and 60 bones, it consists of two main parts:

- The carapace, which is the domed structure on the back fused to the vertebrae and ribs.

- The plastron, a flatter structure on the underside formed by elements of the shoulder girdle, sternum, and abdominal ribs.

These two sections are connected by lateral extensions of the plastron. During embryonic development, the ribs grow sideways into the carapacial ridge, a feature unique to turtles, where they integrate into the dermis and support the shell’s formation.

This process is regulated by fibroblast growth factors, specifically FGF10, which play a key role in signaling growth. Unlike in other vertebrates, the shoulder girdle in turtles is positioned within the ribcage, as the ribs extend outward rather than downward.

The shell itself is covered by epidermal scutes, composed of keratin—the same protein found in human hair and nails. A typical turtle has 38 scutes on the carapace and 16 on the plastron, bringing the total to 54.

Head And Neck

Skull, keratinous beaks, and necks are distinctive features that make Testudines different from other animals for the following points

- Turtle Skull Structure

Turtles have solid, rigid skulls without temporal openings, as found in most reptiles. Instead, their jaw muscles attach to recessed areas at the back of the skull, providing extra strength. Skull shapes vary depending on diet and habitat. Softshell turtles have elongated skulls, while mata mata turtles have broad, flattened skulls suited for suction feeding.

Unlike other reptiles, turtles lack teeth and instead have keratinous beaks. These beaks differ based on diet—sharp-edged beaks help carnivorous turtles slice prey, while serrated beaks allow herbivorous turtles to cut through plants. Their skull structure and beak adaptations enable them to process food efficiently without teeth.

- Keratinous Beaks

Turtles rely on keratin-covered beaks instead of teeth, which continuously grow to compensate for wear. The shape of the beak determines their diet. Carnivorous turtles, like snapping turtles, have sharp, hooked beaks to grasp and tear prey. Herbivorous species, such as tortoises, use broad, serrated beaks to slice through tough plants.

Omnivorous turtles have a combination of both, allowing them to consume varied food sources. This specialized adaptation enables turtles to effectively digest their food, whether they eat plants, small animals, or both.

- Neck Flexibility and Retraction Mechanisms

Turtles have eight neck vertebrae, but their ability to retract their necks varies. Cryptodira (hidden-neck turtles) pull their necks straight into their shells for protection, while Pleurodira (side-neck turtles) bend their necks sideways under the shell.

This flexibility helps turtles hunt, evade predators, and move efficiently. Snake-necked turtles have long, flexible necks for quick strikes at prey, while tortoises have shorter, sturdier necks, allowing them to graze on vegetation. Their unique neck adaptations compensate for the rigid shell, enabling them to interact effectively with their environment.

While Testudines share some similarities with other reptiles, it’s important to distinguish them from groups like Rhynchocephalia, which have unique characteristics.

Which Is The Exception Of Testudines?

Within the Order Testudines, 3 species —Malacochersus tornieri, the family Trionychidae, and Chelus fimbriata —exhibit exceptions to typical turtle characteristics, demonstrating the group’s extraordinary adaptability.

- Malacochersus tornieri

The pancake tortoise (Malacochersus tornieri) is one of the most striking examples, with its uniquely flat, flexible shell—a stark contrast to the conventional domed shell structure. This unusual adaptation evolved in response to its rocky habitat in East Africa, allowing the species to squeeze into narrow rock crevices for protection.

When threatened, these tortoises can wedge themselves so tightly into cracks that predators cannot dislodge them, proving that not all effective defensive strategies require a rigid shell.

- The family Trionychidae

Softshell turtles of the family Trionychidae demonstrate another significant deviation from typical turtle morphology. Instead of hard, bony shells, they possess leathery, pliable carapaces covered with skin.

This adaptation emerged as a response to their highly aquatic lifestyle, allowing for improved hydrodynamics and increased maneuverability in water. The reduced shell weight and streamlined shape enable these turtles to swim faster and chase prey more effectively than their hard-shelled relatives.

- Chelus fimbriata

Perhaps the most fascinating exception is the mata mata turtle (Chelus fimbriata), which has evolved a highly specialized feeding mechanism unique among Testudines. Unlike the typical bite-and-tear feeding method used by most turtles, the mata mata has developed an extraordinary vacuum-feeding system.

When hunting, it can expand its large throat cavity to generate powerful suction, effectively vacuuming prey into its mouth. This adaptation allows it to capture fast-moving fish in murky waters where conventional hunting methods would be less effective.

How are Testudines classified?

- Suborder Pleurodira

Pleurodira, or side-necked turtles, include around 93 species. These turtles have a unique way of retracting their heads: they bend their necks to the side under their shells rather than pulling them straight in. They primarily inhabit freshwater environments in the Southern Hemisphere, including Australia, South America, and Africa. Their elongated, narrow cervical vertebrae allow this distinctive sideways movement, helping them remain alert by keeping one eye open as they withdraw their heads.

There are two families in the Pleurodira suborder, including:

- Family Chelidae: Includes the Austro-American river turtles.

- Family Pelomedusidae: Contains the African side-necked turtles.

- Suborder Cryptodira:

Cryptodira, or hidden-necked turtles, is the largest turtle suborder, with around 260 living species. Unlike Pleurodira, Cryptodira turtles retract their heads straight back into their shells in a vertical motion. They are found in diverse habitats worldwide, ranging from freshwater to marine environments. Their wider, flatter cervical vertebrae provide greater flexibility, allowing them to fully withdraw their heads for protection.

There are four families in the Cryptodira suborder, including:

- Family Testudinidae: Tortoises are adapted for terrestrial life with high-domed shells and short, sturdy legs.

- Family Emydidae: Pond turtles, often found in freshwater environments.

- Family Cheloniidae: Sea turtles, adapted for marine life with streamlined bodies and flippers.

- Family Dermochelyidae: The leatherback turtle, the largest and most unique sea turtle, is characterized by its leathery shell.

The classification of Testudines reflects the diversity and adaptability of turtles and tortoises across various habitats. Here is a simplified diagram for understanding the relationship between the above suborders and families:

Order Testudines

├── Suborder Cryptodira (263 species)

│ ├── Superfamily Testudinoidea

│ │ ├── Family Emydidae

│ │ ├── Family Platysternidae

│ │ ├── Family Testudinidae

│ │ └── Family Geoemydidae

│ ├── Superfamily Kinosternoidea

│ │ ├── Family Kinosternidae

│ │ └── Family Dermatemydidae

│ ├── Superfamily Trionychoidea

│ │ ├── Family Trionychidae

│ │ └── Family Carettochelyidae

│ ├── Superfamily Chelonioidea

│ │ ├── Family Cheloniidae

│ │ └── Family Dermochelyidae

│ └── Family Chelydridae (unassigned)

└── Suborder Pleurodira (93 species)

├── Family Chelidae

├── Family Pelomedusidae

└── Family Podocnemididae

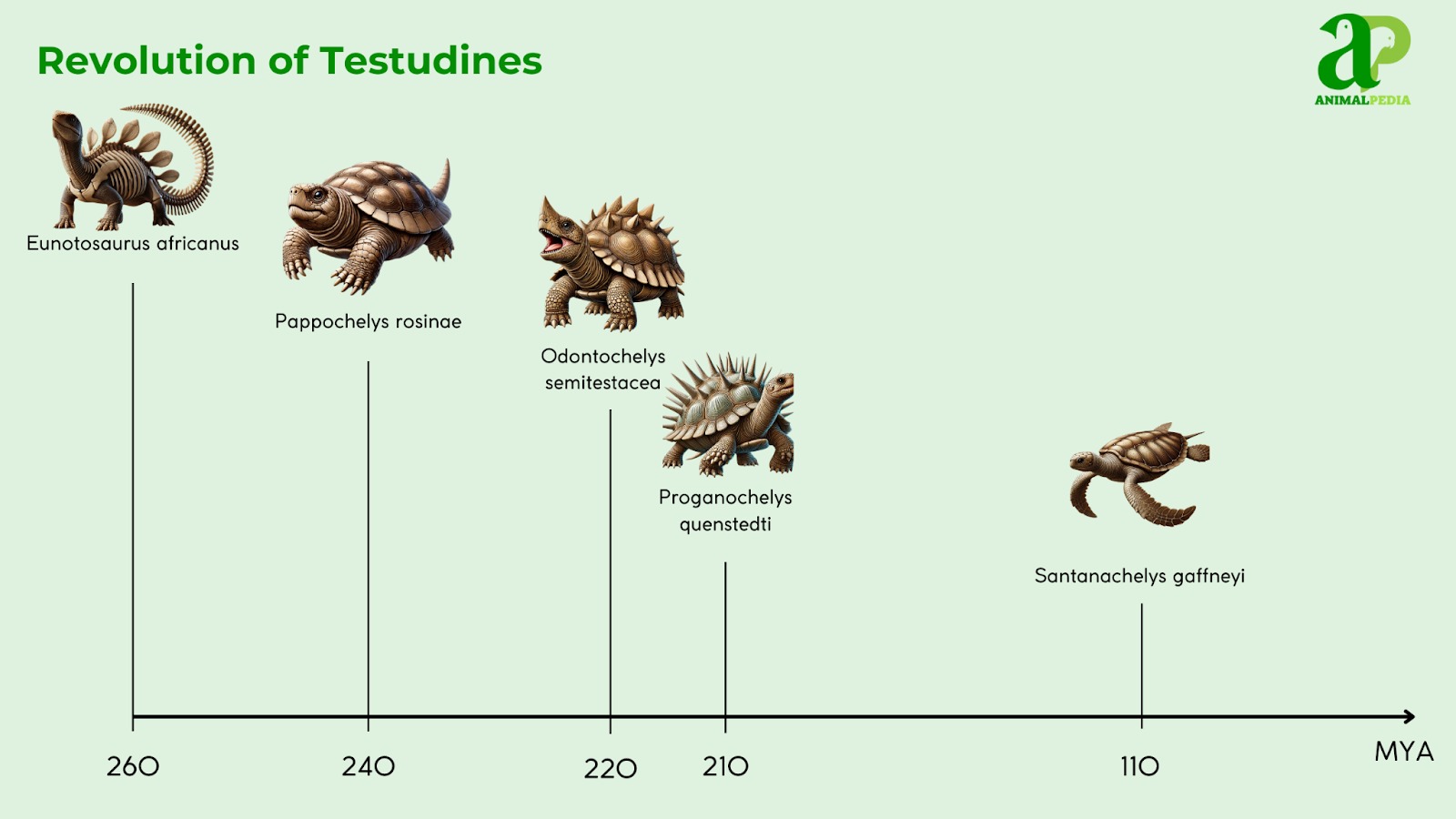

What did Testudines evolve from?

Testudines, commonly known as turtles, evolved from ancient reptiles during the late Triassic period, around 220 million years ago. The evolutionary origins of Testudines have been the subject of extensive research and debate, with attention to both morphological and molecular evidence.

The physical evolution of Testudines has been marked by several adaptations, including:

- 260 Million Years Ago (Late Permian Period):

Testudines are believed to have originated during this time. The discovery of Eunotosaurus africanus in South Africa, an early ancestor with broadened ribs and modified vertebrae, provides evidence of transitional features leading to the iconic turtle shell.

- 240 Million Years Ago (Middle Triassic Period):

The fossil of Pappochelys rosinae, discovered in Germany, represents an intermediate stage between primitive reptiles and modern turtles. This period marks the initial development of the shell, driven by burrowing behavior rather than protection.

- 240–210 Million Years Ago (Triassic Period):

The full evolution of the turtle shell began, involving broadening ribs, vertebrae fusion, and the formation of dermal bones.

- 200–145 Million Years Ago (Jurassic Period):

Testudines developed a unique respiratory system due to their rigid ribcage. Specialized muscles allowed them to breathe efficiently, an adaptation particularly advantageous for aquatic species.

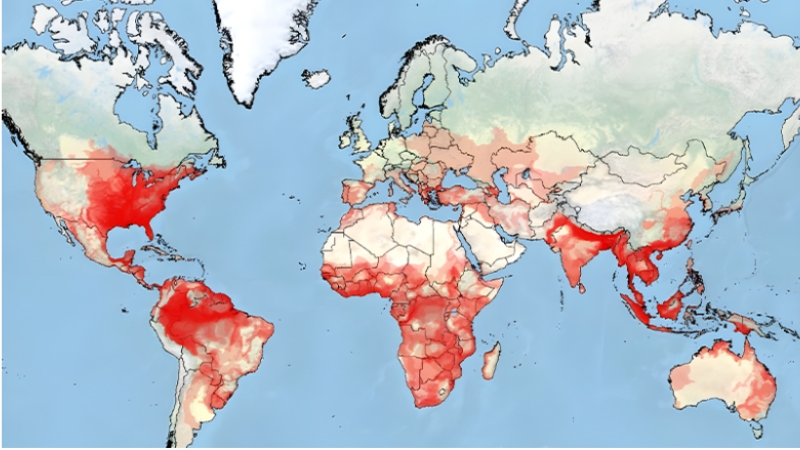

Where do Testudines live?

The distribution of Testudines varies significantly across regions. Southeast Asia hosts the highest diversity with over 90 species, followed by North America with approximately 60 species, particularly concentrated in the southeastern United States. South America supports around 45 species, primarily in the Amazon Basin region.

Several species demonstrate unique geographic isolation, existing only in specific regions. The Hawaiian green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) is endemic to the Hawaiian archipelago, while the Madagascar big-headed turtle (Erymnochelys madagascariensis) is found exclusively in Madagascar.

The Roti Island snake-necked turtle (Chelodina mccordi) exists only on the small Indonesian island of Roti, making it one of the most geographically restricted turtle species in the world. These endemic species highlight the importance of specialized habitat conservation for maintaining Testudines biodiversity.

What are the behaviors of Testudines?

Testudines, including turtles, tortoises, and terrapins, exhibit diverse behaviors that reflect their ability to adapt and thrive across a range of habitats. Their behaviors span diet, locomotion, reproduction, and sensory capabilities.

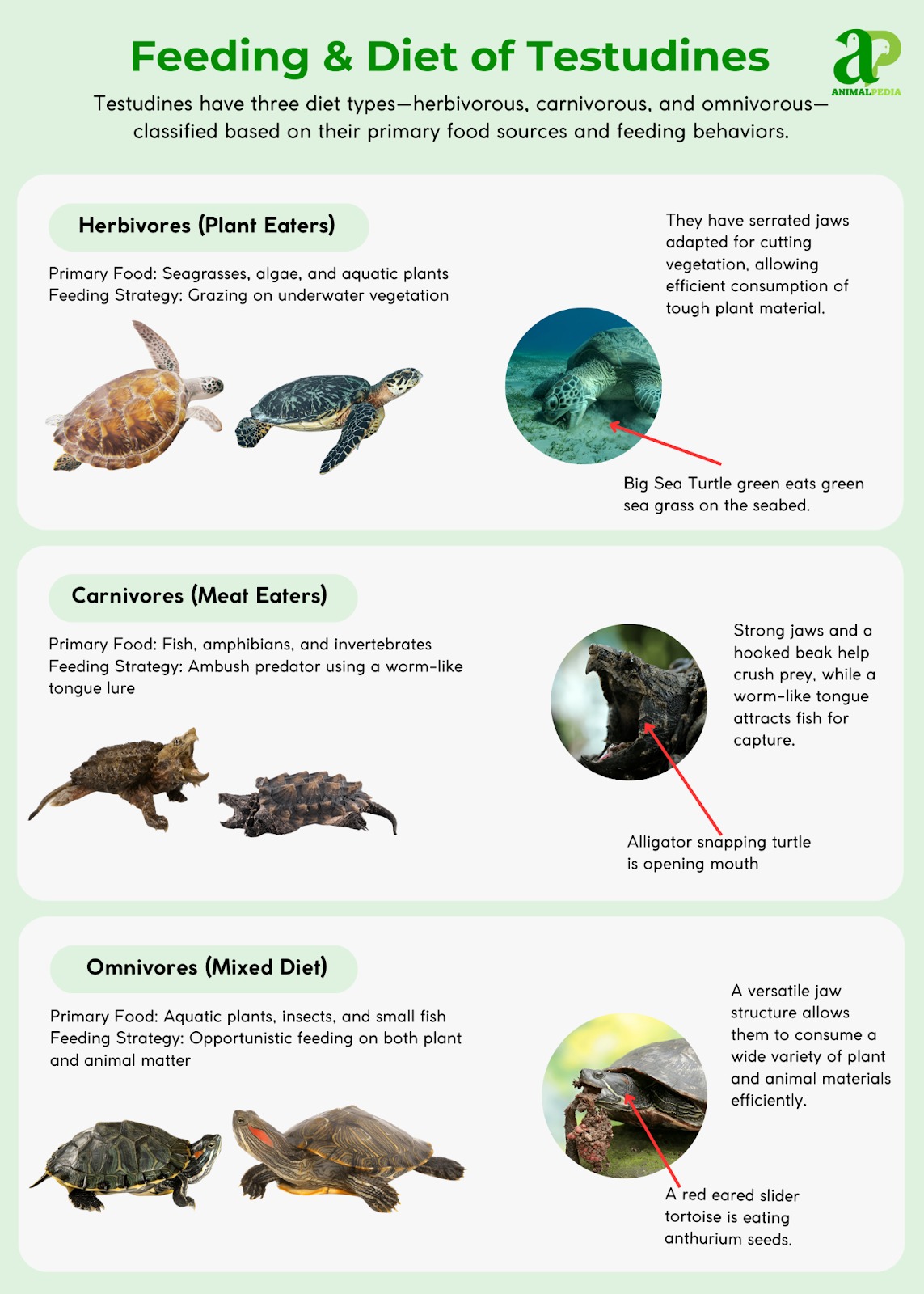

- Dietary Diversity: From herbivorous tortoises like the Galapagos giants to omnivorous and carnivorous turtles, such as green sea turtles and snapping turtles, their feeding habits showcase ecological versatility.

- Locomotion: Terrestrial species have sturdy legs and claws for burrowing and navigating on land, while aquatic species, such as sea turtles, use webbed feet or flippers for efficient swimming.

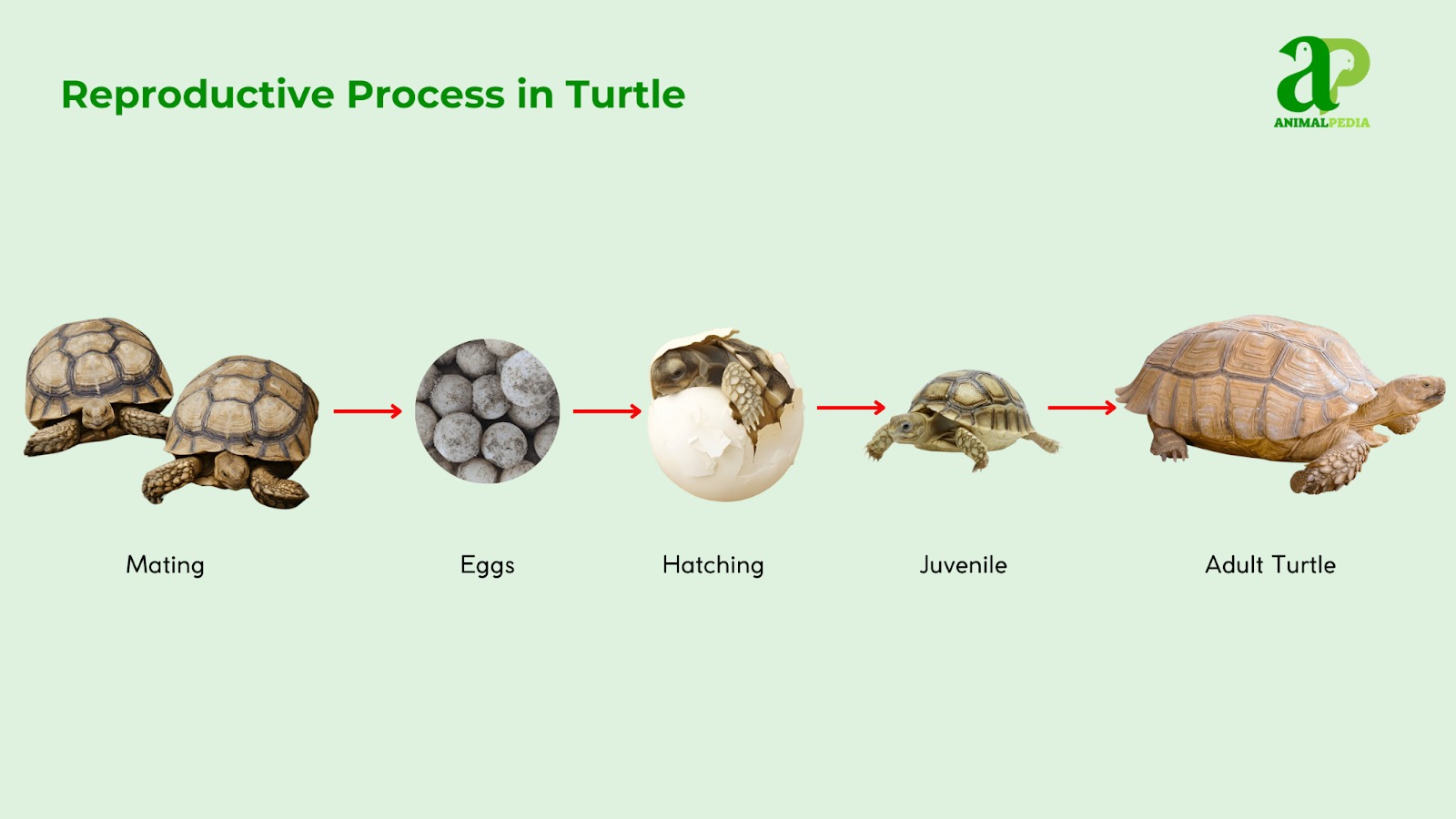

- Reproduction: Testudines lay eggs in nests and use temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD), in which incubation temperature influences offspring sex.

- Sensory Adaptations: With strong olfactory senses, testudines locate food, mates, and nesting sites. They also detect vibrations through their shells and bodies, aiding predator detection and navigation.

While primarily solitary, testudines exhibit social behaviors during mating and nesting seasons. Their adaptations, from hunting techniques to reproductive strategies, highlight their evolutionary success in diverse ecosystems.

Dietary Diversity

The diets of Testudines vary among species as follows.

- Herbivorous Turtles: Their diets often consist of fruits, leaves, and aquatic vegetation. For instance, Heosemys spinosa is known to have a diet largely comprising fruits in captivity, reflecting its natural preference as a forest inhabitant. These species require high fiber and specific vitamins (like Vitamin A) for optimal health.

- Carnivorous Turtles: Their diets include invertebrates, fish, amphibians, and small vertebrates. For example, many freshwater turtles are opportunistic carnivores that consume a variety of animal matter. These turtles require higher protein levels in their diets to support their growth and metabolic functions.

- Omnivorous Turtles: Their diets can include both plant and animal materials. For instance, Cuora amboinensis has been observed consuming up to 100% animal matter in captivity without adverse effects, indicating a high tolerance for animal-based diets. They benefit from a balanced intake of proteins from animal sources and fibers from plants, which supports their digestive health.

The dietary diversity of Testudines reflects their adaptability to different ecological niches, with specific nutritional requirements that vary across species based on their feeding strategies.

Foraging and Hunting Strategies

Turtles (Testudines) use diverse foraging and hunting strategies depending on their species, habitat, and food availability. Their feeding behaviors are shaped by their ecological roles, with distinct adaptations seen in herbivorous, carnivorous, and omnivorous species.

- Herbivorous turtles primarily graze on seagrasses and algae. They often exhibit foraging patch fidelity, repeatedly returning to areas with abundant food. However, when resources decline, they shift their feeding grounds, demonstrating adaptability.

- Carnivorous turtles rely on ambush tactics, lying motionless until prey approaches. Their strong jaws allow them to capture fish, amphibians, and invertebrates, using stealth and patience to maximize success.

- Omnivorous turtles consume both plants and small animals. Their opportunistic feeding behavior allows them to adapt to seasonal and environmental changes by eating whatever is available.

While most turtles forage alone, some species display group foraging to increase efficiency in finding food or reducing predation risks. Additionally, seasonal changes, such as reproduction periods, can alter feeding behaviors, with some turtles reducing foraging while prioritizing nesting activities.

In terms of hunting, some turtles use flippers to manipulate prey, while benthic foragers consume mollusks and crustaceans from the ocean floor. Active hunters chase prey, especially during breeding seasons when energy demands increase.

Social Behavior

Testudines, or turtles, are generally considered solitary animals, but recent studies have revealed a more complex social behavior than previously understood. Their social interactions can vary significantly based on the species, habitat, and life stage.

While predominantly solitary creatures, some testudines exhibit social interactions during specific periods. During nesting season, female sea turtles often gather in large numbers on suitable beaches to lay their eggs.

Similarly, some tortoise species engage in temporary aggregations during mating season, with males competing to mate with receptive females. Overall, however, the order Testudines is characterized by a solitary lifestyle, with individuals primarily focused on individual survival and reproduction.

Limbs and Locomotion

Testudines, commonly known as turtles, exhibit a variety of limb structures and locomotion strategies adapted to their environments, whether aquatic or terrestrial.

- Aquatic Adaptations: Sea turtles have long, paddle-like flippers that allow them to swim efficiently. Their forelimbs generate powerful strokes, while their hind limbs act as rudders for balance and direction. For example, green sea turtles use a figure-eight motion with their front flippers to glide through the water.

- Terrestrial Adaptations: Tortoises have thick, column-like legs with broad, elephant-like feet, built to support their heavy bodies on land. This sturdy structure helps them move across rough terrain. Some species, like gopher tortoises, have flattened front limbs specially adapted for digging burrows.

Comparison of various turtle limb types, highlighting the differences in structure and scale patterns

How Do Testudines Reproduce?

Testudines use the oviparous reproductive strategy, meaning they lay eggs on land. These eggs are typically deposited in shallow nests excavated by the female in loose soil or sand. Below are the key features of their reproduction:

- Nesting Behavior

Most female turtles lay their eggs on dry land, digging a hole and covering the eggs with soil for protection. However, some species lay eggs on the surface among leaves without digging.

The number of eggs varies widely. Small species may lay one to four eggs, while larger species can lay fifty or more. The Asian giant tortoise is known for laying numerous eggs and may briefly guard its nest against predators.

- Egg Incubation and Temperature Dependence

Hatchling sex is influenced by nest temperature. Warmer temperatures typically produce females, while cooler temperatures result in males. Extreme cold can also lead to female offspring.

Depending on species and environmental factors, incubation can last several weeks to months.

- Fertilization and Mating: Males transfer sperm to females through copulation using specialized reproductive organs. During mating season, males may court females with nuzzling or gentle biting. Multiple males often compete for a single female.

- Parental Care: Most turtles abandon their nests after laying eggs. However, species like the Asian giant tortoise may briefly stay to protect the nest from predators.

- Life Cycle: Newly hatched turtles are highly vulnerable to predators and must rely on instinct to find food and shelter.

Unfortunately, due to the lack of a protective shell and the vulnerability of nests, both eggs and hatchlings face significant predation risks. This lack of parental care necessitates a high clutch size for these reptiles, often numbering in the dozens, to ensure some offspring survival.

Senses

Turtles rely on a combination of vision, smell, vibration detection, and magnetic sensing to navigate their environments, find food, and avoid predators.

- Vision

Turtles can detect shapes, colors, and movement, which helps with foraging, mate selection, and predator avoidance, though not as sharply as those of other reptiles.

Aquatic turtles, Testudines, have eyes adapted for underwater vision, but are generally shortsighted in the air. They can see well in bright light conditions, which is crucial for their aquatic lifestyle. Their eyes are equipped with both rods and cones, allowing them to perceive color and detect bioluminescence, which aids in locating prey in dark waters

- Olfaction (Sense of Smell)

Turtles have a well-developed sense of smell, which is essential for locating food, identifying mates, and navigating. Their nasal cavity contains olfactory receptor neurons, which detect both airborne and waterborne odors. This ability enables sea turtles to return to breeding grounds using scent cues and allows males to attract females with pheromones.

- Vibration Sensitivity

Turtles detect ground and water vibrations through specialized structures in their inner ear and lateral line system. This sensitivity aids in predator detection, navigation, and communication. Some species, like box turtles, use low-frequency sounds, while sea turtles rely on wave vibrations to stay on course during migration.

- Magnetic Sensing

Turtles also possess a magnetic sense, allowing them to orient themselves and navigate long distances, particularly in open ocean environments.

These sensory adaptations help turtles thrive in diverse habitats, ensuring their survival and reproduction.

What is the relationship between Testudines and Humans?

The relationship between Testudines, the order encompassing turtles, terrapins, and tortoises, and humans stretches back across millennia, woven into the fabric of various cultures and reflected in modern-day interpretations. This intricate tapestry encompasses symbolic significance, artistic portrayals, and even practical interactions.

- Mythology and Symbolism

Throughout history, Testudines have held prominent roles in diverse mythologies. Their longevity, symbolized by their hard shells and slow aging, has often linked them to concepts of wisdom and immortality.

In Chinese mythology, the Black Tortoise represents the north and longevity, while in Hindu creation myths, the Kurma, a giant tortoise, serves as the foundation of the Earth. These symbolic associations have transcended cultures, solidifying the Testudine image as an embodiment of resilience and enduring spirit.

- Modern Representations

The enduring influence of Testudines extends into the contemporary world, finding expression in various artistic and cultural realms. Literature, from Aesop’s fables to Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland,” features turtles as characters embodying wisdom, patience, and perseverance.

In art, Testudines have captivated artists across mediums, with their unique forms and intricate patterns inspiring sculptures, paintings, and even jewelry. Popular culture further cements its presence through iconic characters like Michelangelo from the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Crush from Disney’s Finding Nemo, highlighting their positive and relatable qualities.

This multifaceted relationship between Testudines and humans underscores the enduring impact these creatures have had on our imagination and cultural understanding. Their symbolic significance, artistic representation, and even practical interactions continue to shape our perception of these captivating reptiles in the modern world.

Are Testudines going to become endangered?

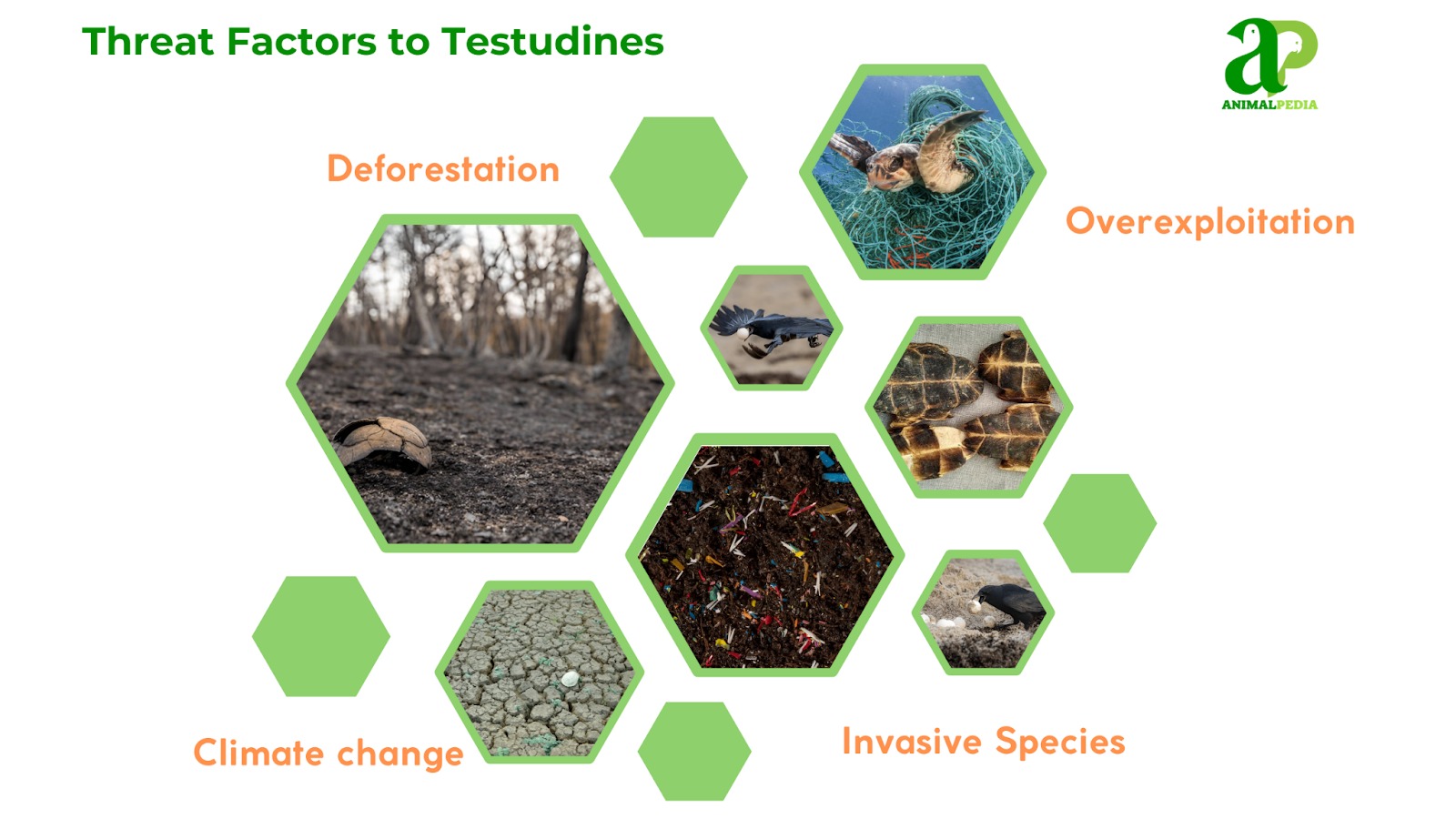

- Habitat Loss

Urbanization, agriculture, and deforestation are rapidly destroying turtle habitats, reducing nesting sites, food sources, and overwintering areas. This disrupts essential ecological processes, especially for freshwater species that depend on stable water quality and temperature. Additionally, pollution from chemicals and plastics contaminates aquatic environments, weakening turtles’ immune systems, reducing reproductive success, and causing injuries or death through entanglement.

- Overexploitation

Turtles face intense pressure from illegal wildlife trade, food consumption, and traditional medicine. Many freshwater species are collected unsustainably for the pet market, while turtle meat remains in high demand in certain regions. Traditional medicine, despite lacking scientific backing, further threatens populations. Addressing this requires stronger regulations, sustainable alternatives, and public awareness to reduce demand and support conservation.

- Climate Change

Rising temperatures affect sex determination in hatchlings, leading to skewed female ratios, which can disrupt population balance. Sea level rise also threatens nesting beaches, eroding crucial breeding grounds and reducing reproductive success.

- Invasive Species

Non-native species compete with turtles for food and basking sites, reducing resources and slowing growth. Many also prey on eggs and hatchlings, threatening recruitment and long-term survival. Effective control strategies, including removal, habitat management, and biological control, are essential to protect native populations.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the difference between a turtle, a tortoise, and a terrapin?

Turtles, tortoises, and terrapins are all reptiles from the order Testudines, but they differ in their habitats. Turtles are primarily water-dwelling creatures, with species living in both the sea and freshwater environments. They have flat, streamlined shells and flipper-like limbs for efficient swimming.

Tortoises, on the other hand, are land-dwellers with domed shells and stumpy, elephantine feet for walking. Terrapins live in both land and freshwater environments. However, these terms can be used differently depending on the region and the type of English used.

How long do turtles and tortoises live? Are there any in my state?

The lifespan of turtles and tortoises varies greatly by species. Some species may only live 10 to 20 years, while others can live up to 150 years or more. For instance, the Galapagos tortoise is one of the longest-lived animals on Earth, with a lifespan of over 150 years.

How do turtles breathe underwater?

Turtles cannot breathe underwater in the same way fish do. They need to come up to the surface to breathe air. However, some turtles have evolved to absorb oxygen from the water through their skin, specifically through an area called the cloaca, allowing them to stay underwater for extended periods.

Why is the shell of my pet turtle smooth, while the shells of some wild turtles are bumpy?

The texture of a turtle’s shell can vary due to several factors, including the species of the turtle and its environment. Some turtles have naturally more textured or bumpy shells, which may be an adaptation to their specific habitat or lifestyle. In some cases, a bumpy shell can also be a sign of a condition called pyramiding, which can occur when a turtle doesn’t have access to a proper diet or adequate housing.

How do scientists determine the age of a turtle, given that they can live for such a long time?

Determining a turtle’s age is tricky. Scientists often count growth rings on shell scutes, with each ring roughly representing a year, though this becomes less reliable as turtles age. Comparing shell size to typical growth rates for the species offers another estimate, but both methods are approximate.

Despite their ancient lineage and adaptations, turtles face serious threats, including habitat loss and climate change. Conservation efforts like habitat protection, research, and captive breeding are vital to preserve these extraordinary creatures and their ecological roles for future generations.

Testudines, a group of reptiles, thrive in diverse habitats and captivate with their unique adaptations like protective shells and temperature-dependent sex determination. Their evolutionary journey, spanning 260 million years, highlights their resilience and ecological significance. From aiding nutrient cycling to inspiring cultural myths, they play vital roles in nature and human narratives.

However, challenges like habitat loss and overexploitation endanger species such as the leatherback sea turtle and the Yangtze giant softshell turtle. By supporting conservation efforts, we can safeguard these ancient creatures, ensuring their continued contribution to biodiversity and the stories they inspire.