Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas), the sole species in their genus, feature streamlined bodies with olive to dark brown carapaces and powerful, paddle-like flippers. Adult specimens reach 3–4 feet (0.9–1.2 meters) in length and weigh 300–400 pounds (135–180 kilograms). Their heart-shaped shell, often mottled with darker patterns, provides effective camouflage in marine environments.

Their scientific name reflects their distinctive greenish fat deposits, a direct result of their herbivorous diet. These magnificent types of reptiles inhabit tropical and subtropical waters, with major nesting concentrations in Hawaii, Costa Rica, and Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Unlike other sea turtles, green turtles maintain a plant-based diet, primarily consuming seagrasses and algae, which has led to specialized, robust jaw structures.

These marine voyagers navigate coastal waters, undertaking migrations spanning thousands of miles between feeding grounds and nesting beaches. Distributed throughout the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, they prefer warm waters near coral ecosystems and seagrass meadows. Their substantial size and sturdy carapace deter most predators, though their eggs are vulnerable to crabs and shorebirds.

Rather than hunting as predators, green turtles serve as peaceful grazers in marine ecosystems. While juveniles consume jellyfish and invertebrates, adults specialize in marine vegetation. Human activities pose significant threats through fishing gear entanglement and coastal development that destroys critical habitat.

Reproduction occurs every 2–4 years, with peak mating season from June to September. Females deposit 100–200 eggs on their natal beaches, which incubate for 50–60 days. Hatchlings face a perilous journey to the sea, and those that survive reach maturity in 20–30 years. Their average lifespan reaches 70–80 years. This examination explores their morphology, ecological significance, and conservation challenges.

In this article, we explore the fascinating world of Green Sea Turtles, examining their unique characteristics, behaviors, and habitats.

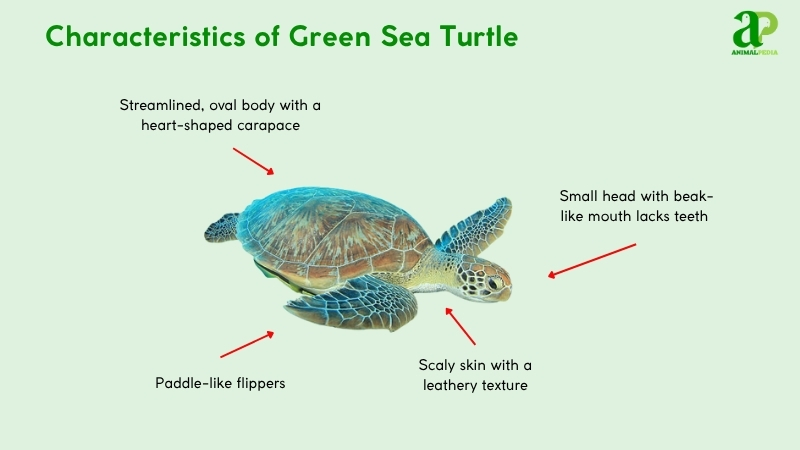

What do the Green Sea Turtles look like?

Green sea turtles have streamlined, oval bodies with heart-shaped shells measuring 3–4 feet long. Their smooth carapace displays olive to dark brown colors with mottled patterns, perfect for hiding in seagrass beds. Their scaly skin ranges from gray to greenish tones. They have small heads with large, dark eyes for underwater vision and a beak-like mouth without teeth, ideal for plant grazing.

Their short, retractable necks, while their broad bodies are powered by strong, paddle-like flippers. These flexible, scaleless flippers propel them up to 22 miles daily through ocean waters. Their tails are short and barely visible.

Unlike loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta), green turtles have smoother, less bulky shells without reddish-brown coloration. They differ from hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) with less pointed beaks, reflecting their herbivorous diet. Their flippers, longer than those of leatherbacks (Dermochelys coriacea), provide excellent maneuverability in coastal habitats. These distinctive traits help scientists identify green turtles in marine ecosystems.

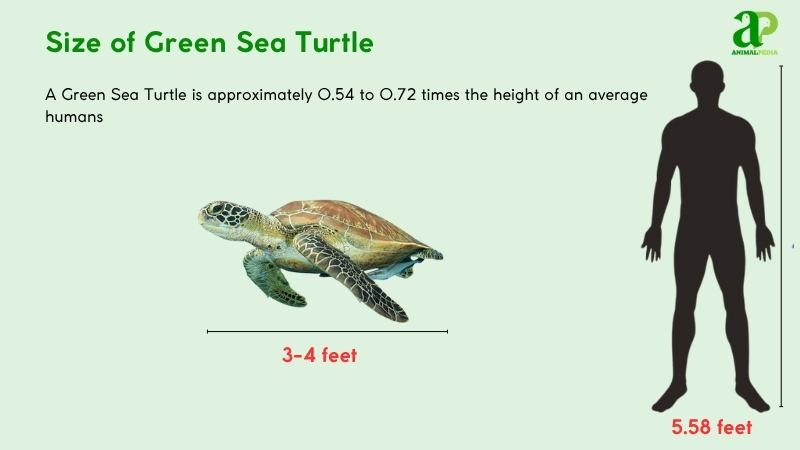

How big do Green Sea Turtles get?

Adult green sea turtles average 3–4 feet (0.9–1.2 meters) in length and weigh 300–400 pounds (135–180 kilograms). Their carapace, measured snout-to-tail, typically spans 3.3 feet (1 meter), supporting their herbivorous lifestyle in tropical waters.

The largest recorded green turtle, found in the Galápagos Islands, measured 5 feet (1.5 meters) and weighed 500 pounds (227 kilograms), documented in a 2018 study by Seminoff et al.

Males and females show minimal size differences, with females slightly larger to support egg production. Males have longer tails but similar carapace lengths.

| Trait | Male | Female |

| Length | 3–4 ft (0.9–1.2 m) | 3.2–4.2 ft (1–1.3 m) |

| Weight | 300–380 lb (135–172 kg) | 320–400 lb (145–180 kg) |

What are the unique physical characteristics of the Green Sea Turtles?

Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) have distinct physical traits that set them apart from other marine chelonians. Their herbivorous jaw structure stands unique among sea turtles. Their serrated, beak-like mandible cuts seagrasses and algae efficiently—unlike the jaws of carnivorous relatives like loggerheads (Caretta caretta) or hawksbills (Eretmochelys imbricata).

The heart-shaped carapace of green turtles measures 3–4 feet (0.9–1.2 meters). This shell appears smooth and waxy, lacking the ridges or spines found in other species, resulting in optimal hydrodynamic efficiency in water. Their carapace features non-overlapping scutes, in contrast to the imbricated, overlapping plates of hawksbills.

Research by Bjorndal and Bolten (2017) highlights the robust, serrated mandible. This adaptation enables effective grazing on marine vegetation—a capability absent in other sea turtle species. Their paddle-like flippers, each with a single claw, extend proportionally longer than those of leatherbacks (Dermochelys coriacea). These specialized limbs help navigate precisely through dense seagrass meadows (Thalassia testudinum) and algal beds where they feed.

These morphological adaptations evolved specifically for their plant-based diet and coastal foraging behavior, establishing green turtles’ distinctive ecological niche in marine ecosystems.

How do Green Sea Turtles adapt with their unique features?

Anatomy

Green sea turtles possess specialized anatomical systems tailored for marine life. These systems support their herbivorous diet, long migrations, and survival in dynamic ocean environments, as studied in tropical and subtropical waters.

- Respiratory System: Lungs enable breath-holding dives up to 5 hours, with efficient oxygen storage supporting extended foraging in seagrass beds.

- Circulatory System: A three-chambered heart powers blood flow, maintaining stamina for migrations over 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) across oceans.

- Digestive System: A serrated jaw and long intestine process seagrasses and algae, maximizing nutrient absorption for their plant-based diet.

- Excretory System: Kidneys excrete salt via specialized glands near the eyes, balancing osmosis in saline environments during long oceanic journeys.

- Nervous System: A developed brain and optic nerves enhance navigation, using geomagnetic cues for precise nesting beach returns.

These systems, refined by evolution, enable green turtles to thrive in coastal and open-ocean habitats, ensuring efficient foraging, reproduction, and predator avoidance.

Where do Green Sea Turtles live?

Green sea turtles live in tropical and subtropical waters throughout the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans. Their main nesting beaches include Hawaii’s French Frigate Shoals, Costa Rica’s Tortuguero, and Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. They forage extensively in the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico.

These marine reptiles thrive in warm waters between 68–77°F (20–25°C). Their habitat ecosystem consists of seagrass meadows and coral reef systems that provide both food and shelter. This environment supports their primarily herbivorous diet and offers protection from natural predators. These marine habitats enable their impressive long-distance migrations, often spanning 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) between feeding grounds and nesting sites.

Chelonia mydas (scientific name) has inhabited Earth’s oceans for over 100 million years, as evidenced by fossil records. Their migration patterns rely on geomagnetic navigation, a phenomenon documented by Lohmann and colleagues (2018). Stable coastal environments ensure these keystone species fulfill their ecological role as marine grazers in ocean ecosystems.

How do seasonal changes affect their behavior?

Green sea turtles adjust their behaviors across two primary seasons in tropical and subtropical waters, driven by temperature and resource shifts. These changes optimize reproduction, foraging, and migration.

- Breeding Season (June–September): Turtles migrate to natal beaches, with females laying 100–200 eggs. Males compete for mates, leading to increased courtship displays.

- Non-Breeding Season (October–May): Turtles focus on foraging in seagrass beds, reducing migration. Juveniles feed heavily to support growth, while adults conserve energy.

These seasonal shifts, documented by Bjorndal and Bolten (2017), align with environmental cues, ensuring survival and reproductive success in dynamic marine habitats.

What is the behavior of Green Sea Turtles?

Green sea turtles exhibit behaviors tailored to their marine lifestyle, balancing foraging, migration, and reproduction across vast oceans. Their actions reflect adaptations to tropical and subtropical waters, ensuring survival in dynamic environments.

- Feeding Habits: Adults graze on seagrasses and algae, cropping with serrated jaws. Juveniles consume jellyfish and invertebrates.

- Bite & Venomous: Non-venomous; their bite is weak and harmless. They avoid confrontation, retreating when threatened.

- Daily Routines and Movements: They forage daily, resting in reef crevices. Migration spans 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) to nesting sites.

- Locomotion: Paddle-like flippers enable swift swimming, allowing daily distances of up to 22 miles (35 kilometers). Dives last up to 5 hours.

- Social Structures: Solitary except during mating, they gather at nesting beaches. No lasting social bonds form.

- Communication: Low-frequency vocalizations aid mating. Visual cues guide hatchlings to the sea.

These behaviors highlight their ecological role. Their feeding habits, critical to marine ecosystems, merit deeper exploration for their impact on seagrass health.

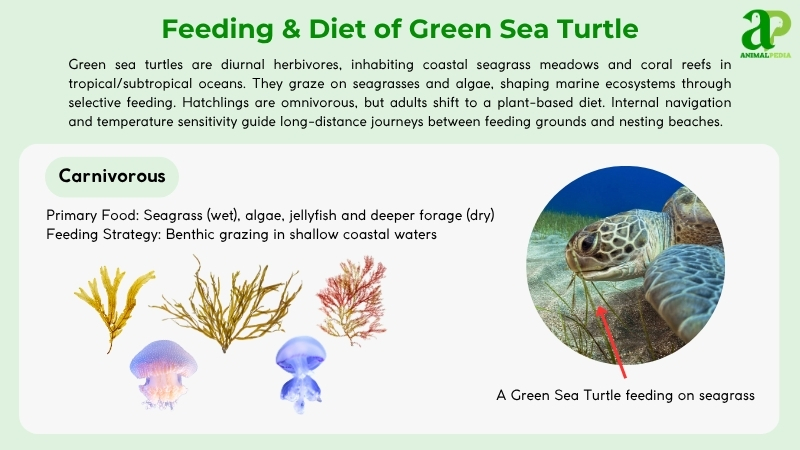

What do Green Sea Turtles eat?

Green sea turtles are primarily herbivorous, favoring seagrasses and algae, with seagrass beds being their preferred foraging grounds. They are not carnivorous and do not attack humans. Their serrated jaws crop vegetation into small pieces, which they swallow whole. Large items are avoided to prevent choking or digestive blockages. Their diet supports coastal ecosystem health by grazing on vegetation.

- Diet by Age:

Hatchlings and juveniles are opportunistic omnivores, consuming jellyfish, sponges, small crustaceans, and algae to meet the demands of rapid growth. This mixed diet supports energy needs during early development. As turtles mature, they transition to an exclusively herbivorous diet, mainly consuming seagrasses such as Thalassia testudinum and Halophila species, which are essential for adult health and reproductive readiness.

- Diet by Gender:

Males and females exhibit no significant dietary differences. Both sexes forage in similar habitats and consume the same plant matter. Unlike some species, there is no evidence of gender-based nutritional variation or competitive feeding behavior in green sea turtles.

- Diet by Seasons:

During wet seasons (June–September), warmer temperatures and increased sunlight enhance seagrass growth, allowing more frequent and prolonged grazing. In dry seasons, reduced productivity pushes turtles to deeper waters or forces them to exploit alternative vegetation, demonstrating foraging flexibility and ecological resilience.

How do Green Sea Turtles hunt their prey?

Green Sea Turtles are primarily herbivores, not predators. They feed by grazing on seagrass meadows and algal beds in shallow coastal waters. Their serrated beaks are specially adapted to scrape and tear vegetation. Unlike carnivorous species, they don’t hunt prey by ambush.

These marine reptiles have excellent underwater vision, which helps them locate their food sources. As they mature, Green Sea Turtles transition from an omnivorous diet to a predominantly plant-based one. They use their powerful front flippers to navigate efficiently through water while feeding.

Green Sea Turtles are methodical foragers rather than hunters. They spend hours grazing in seagrass meadows, helping maintain healthy marine ecosystems through their feeding. Their digestive systems are specialized to process fibrous plant material, containing beneficial gut microbes that aid in breaking down cellulose.

Are Green Sea Turtles venomous?

In the peaceful waters they navigate, Green Sea Turtles are known not for their venom but for their gentle and fascinating behavior. These marvelous creatures are serene inhabitants of the ocean, inviting you to witness their intriguing ways without any concerns. Green Sea Turtles don’t have venomous abilities; instead, they rely on their peaceful demeanor and impressive swimming skills to thrive in their watery home.

When encountering Green Sea Turtles, you’ll observe their tranquil nature as they elegantly glide through the water in search of food. These gentle beings are herbivores, mainly feeding on seagrasses and algae, demonstrating their peaceful nature with each bite. Watching them peacefully munch on vegetation can be a truly sight, underscoring the importance of peaceful coexistence with the marine world.

Custom Quote: “Green Sea Turtles embody the beauty and tranquility of the ocean, reminding us to appreciate and respect the underwater ecosystem.”

When are Green Sea Turtles most active during the day?

Green Sea Turtles are most active during daylight hours, especially in the morning and mid-day. They spend this time feeding on seagrass beds and algae, their primary food sources. Unlike predatory tactics described previously, these herbivorous reptiles graze peacefully, using their serrated jaws to crop vegetation.

During peak activity periods, Green Sea Turtles exhibit foraging behaviors that align with optimal sunlight conditions. They navigate between feeding grounds and resting areas with deliberate movements. Their diurnal pattern allows them to use excellent vision to locate preferred seagrass species and avoid potential threats.

By afternoon, their activity typically decreases as they seek shelter among reef structures or sandy bottom areas. This circadian rhythm helps conserve energy and reduces exposure to predators. Marine biologists observe that water temperature also influences activity levels, with turtles becoming more active in warmer waters during daylight periods.

How do Green Sea Turtles move on land and water?

Green Sea Turtles move distinctly in both environments. On land, they drag their 300-to 400-pound bodies with alternating front flippers, creating a slow but determined crawl. Their terrestrial movement resembles a heavily loaded rowing motion, allowing females to reach nesting sites during the breeding season.

In water, these marine reptiles transform completely. Their hydrodynamic shells and powerful, wing-like front flippers enable them to cruise efficiently at speeds of 1.5-5.8 mph. They use their rear flippers as rudders, creating a flying motion underwater rather than a swimming stroke. This adaptation lets them travel thousands of miles during migrations between feeding and nesting grounds.

The contrast between their terrestrial limitations and aquatic grace highlights their evolutionary adaptation to marine life. While awkward on beaches, they achieve biomechanical efficiency in ocean currents, demonstrating how their anatomy is optimized for their primarily aquatic existence while maintaining the minimal land mobility required for reproduction.

Do Green Sea Turtles live alone or in groups?

Green Sea Turtles (Chelonia mydas) live mostly solitary lives in ocean ecosystems. They come together only during mating seasons and for communal nesting.

During reproduction periods, males and females congregate in coastal waters for courtship. Females then migrate to specific beaches, forming rookeries – collective nesting grounds where multiple turtles lay eggs simultaneously. A female digs a nest cavity in the sand, deposits her clutch of 100-200 eggs, and occasionally other females participate in this crucial reproductive behavior.

Green sea turtles are one of the most well-known marine reptiles, celebrated for their graceful movements and long migrations. However, they are just one member of a much larger family of creatures. These turtles belong to the broader group of testudines species, which includes a variety of land and marine turtles.

After these social aggregations conclude, the marine reptiles resume their solitary existence. They navigate vast oceanic habitats independently, feeding primarily on seagrass and algae in their preferred foraging territories. The migratory patterns of these endangered chelonians involve both periods of isolation and brief but essential social interactions that ensure species survival.

How do Green Sea Turtles communicate with each other?

Green Sea Turtles communicate through a combination of body movements and sensory signals. Despite not being able to talk, these majestic creatures use gestures, such as head bobbing and flipper movements, to convey messages of dominance or courtship. When searching for food, they signal other turtles by emitting vibrations to show the location of a feeding spot. By relying on their senses of sight, touch, and smell, Green Sea Turtles can detect their peers and communicate effectively in their underwater habitat.

During nesting season, female Green Sea Turtles produce unique sounds while laying eggs, potentially to coordinate their nesting activities. These vocalizations also serve to identify individuals and strengthen social connections within the turtle community. Through a mix of physical cues and sensory communication, these turtles skillfully navigate their marine environment, showcasing their abilities to connect and interact with one another.

How do Green Sea Turtles reproduce?

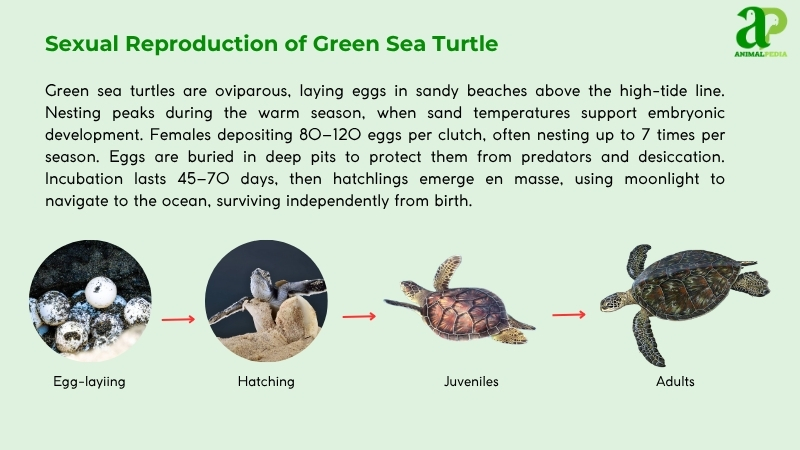

Green sea turtles reproduce through egg-laying on beaches. Their breeding season runs from June to September. Males court females offshore using distinctive flipper movements. Females mate with multiple males and store sperm for later fertilization. Mating occurs in shallow waters and lasts several hours.

Females dig nests on their natal beaches, laying 100–200 eggs per clutch. Each egg weighs about 45 grams. They cover the eggs with sand for protection but provide no parental care afterward. Both parents return to the feeding grounds. Coastal development and predators threaten nesting success, as demonstrated by the 2017 storm impacts in Costa Rica.

Hatchlings emerge after 50–60 days, typically at night to avoid predators. They instinctively head toward the ocean. Juvenile turtles develop in open seas, feeding on plankton and jellyfish. They reach sexual maturity after 20–30 years. Green sea turtles live 70–80 years on average. While hatchling mortality rates are high, adults have long survival rates according to Lohmann’s 2018 research.

How long do Green Sea Turtles live?

Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) live 60 to 70 years in the wild. Some specimens reach beyond 80 years under ideal conditions. Their life cycle includes a lengthy juvenile stage, with sexual maturity occurring between 20 and 40 years, varying with habitat quality and nutrition.

Longevity is consistent between sexes. After maturation, these marine reptiles often migrate thousands of kilometers to return to their birthplace beaches for reproduction. Their exceptional lifespan and breeding site fidelity are crucial characteristics for sustaining populations in threatened ocean ecosystems.

What are the threats or predators that Green Sea Turtles face today?

Green sea turtles face numerous threats impacting their survival across tropical and subtropical oceans. Predation and human activities exacerbate these challenges, threatening population stability.

- Habitat Loss: Coastal development destroys nesting beaches, reducing reproductive success by 30% in heavily urbanized areas.

- Climate Change: Rising sea temperatures disrupt sex ratios, producing more females, and flooding nests, lowering hatchling survival by 20%.

- Bycatch: Fishing nets entangle turtles, resulting in 50,000 annual deaths globally and depleting adult populations.

- Pollution: Plastic ingestion kills 1,000 turtles yearly, blocking digestive tracts and causing starvation.

- Poaching: Illegal egg harvesting reduces hatchling output, with 10% of nests raided in some regions.

Predators include crabs, birds (e.g., frigatebirds), and fish (e.g., groupers), which target eggs and hatchlings. Adults face tiger sharks, which exploit their size during migrations.

Human impacts, such as fishing and coastal development, have reduced populations by 50% since the 1950s, according to Fuentes et al. (2016). Pollution and boat strikes further degrade habitats, necessitating urgent conservation to curb declines.

Are Green Sea Turtles endangered?

Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) are officially classified as Endangered on the IUCN Red List. This 2015 assessment confirms their vulnerable status resulting from multiple threats.

Habitat destruction, illegal harvesting, and climate change the primary challenges to their survival. Bycatch in fishing gear also causes significant mortality among these marine reptiles.

Population figures show roughly 85,000-90,000 nesting females globally. Key rookeries include Tortuguero, Costa Rica (4,000-6,000 females annually) and Hawaii’s French Frigate Shoals (1,000-2,000 females). Many regions have experienced population declines of 50% or more since the 1950s.

Some conservation success is evident in Pacific populations, which show a 5% annual growth rate in protected areas. Despite these gains, the species faces ongoing threats requiring continued protection measures to ensure recovery of this keystone marine reptile.

What conservation efforts are underway?

Green sea turtles face vigorous conservation efforts to address habitat destruction, accidental capture, and illegal hunting. The Sea Turtle Conservancy (founded 1959) and World Wildlife Fund lead crucial initiative,s including beach protection programs and marine sanctuaries. Since the 1980s, protection efforts in Florida and Hawaii have increased nesting populations by 5% yearly in specific areas.

The Endangered Species Act (1973) protects these chelonians in U.S. territories by banning hunting, collection, and disturbance. CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) prohibits global trade of turtle products. Turtle Excluder Devices became mandatory in U.S. fisheries in 1987, cutting bycatch mortality by half.

Captive breeding initiatives, notably the Cayman Turtle Centre (established 1968), have bolstered wild populations by releasing 31,000 juvenile turtles by 2017. Florida’s nesting sites showed recovery from 464 nests (1989) to 39,000 (2017) according to Seminoff’s research. Conservation zones in Cyprus have tripled the number of nests since 2018. These successes demonstrate the effectiveness of legal protection, local community involvement, and sustainable tourism in the face of global challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do Green Sea Turtles Have Individual Personalities?

Yes, green sea turtles do have individual personalities. Just as you and others do, they exhibit unique traits and behaviors that set them apart. Their personalities vary, adding to the diversity of these amazing creatures.

Can Green Sea Turtles Hear Well Underwater?

Yes, green sea turtles can hear well underwater. Their auditory systems are adapted to detect vibrations in water better than in air. This helps them communicate, find food, and navigate their ocean environment effectively.

How Long Can Green Sea Turtles Hold Their Breath?

Green sea turtles can hold their breath underwater for 4 to 7 minutes, especially during feeding or resting. Green sea turtles have adapted to stay submerged for extended periods by slowing their heart rate.

Do Green Sea Turtles Have a Sense of Smell?

Yes, green sea turtles have a vital sense of smell. They use it to find food, navigate the ocean, and locate nesting sites. Their acute olfactory abilities play an essential role in their survival and daily activities.

Are Green Sea Turtles Affected by Climate Change?

Yes, green sea turtles are affected by climate change. Rising temperatures can alter their nesting beaches, impacting hatching success. Changes in ocean currents and storms can also affect their feeding grounds and migration patterns.

Conclusion

Green Sea Turtles (Chelonia mydas) represent keystone species in marine ecosystems. Their distinctive appearance, migration patterns, and feeding behaviors contribute to ocean health. These endangered reptiles maintain seagrass beds through grazing, creating habitats that support numerous marine species.

Marine conservation efforts must prioritize protecting turtles to preserve biodiversity and balance ecosystems. Their population decline signals broader environmental concerns, including habitat destruction, climate change, and ocean pollution.

The preservation of these ancient mariners requires international cooperation, habitat protection, and public education. By safeguarding nesting beaches and migration corridors, we ensure these creatures continue their 100-million-year evolutionary journey. Understanding these marine reptiles isn’t just scientific curiosity—it’s essential for maintaining healthy oceans for future generations.